Introduction

John Jay is regarded as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States of America. There, he is well known as Statesman and first Chief Justice of the United States. In Australia, we know relatively little about him, compared to other American Statesmen and judges. John Jay did leave an enduring judicial legacy, including for Australian law. It is worth exploring that legacy in these pages.

Background

John Jay was born in Manhattan, New York City on 12 December 1745.[1] He was of French Huguenot and Dutch heritage. The son of a wealthy merchant, he grew up on the family farm in Rye, New York. He went to a grammar school at New Rochelle, where his studies included French. From 1760 to 1764, he went to King’s (now Columbia) College and there received a classical education.

Jay’s childhood home in Rye, New York

He determined on a career in law. To this end, he began by studying Grotius. Two weeks after graduating from College, he was apprenticed to barrister Benjamin Kissen.

In 1768 he was admitted to the New York Bar, and formed a partnership with Robert R Livingston Jr.[2] He built up a substantial and successful practice and became known for his brilliant oratory.[3]

In 1774, he was elected one of the New York delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In 1775 he was also a New York delegate to the Second Continental Congress, which body adopted the Articles of Confederation in 1777. He did not sign the Declaration of Independence of 4 July 1776 because he had also been appointed delegate of the New York Provincial Assembly in April of that year, which refused to allow him leave of absence to travel to Philadelphia. But he proposed the resolution at the New York Provincial Assembly that the Declaration of Independence be adopted by New York State.

John Jay played a pivotal role in drafting the New York Constitution, which was adopted by the New York Provincial Assembly in 1777. He was immediately appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature of New York established under the said New York Constitution, which was intended to continue, or replace, the Colonial Supreme Court which had been in existence since 1691. However, within British lines Judge Ludlow also continued to sit as judge of that latter body.

Minimal records have survived of his work as state Chief Justice.[4] Jay CJ’s work on that Court was interrupted when the New York legislature resolved that he be appointed to make representations to the Continental Congress on the settlement of a dispute between New York and the region which was to become Vermont. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed President of the Congress.

John Jay resigned as Chief Justice on 10 August 1779, thereby making himself available to serve in that and other capacities.

In 1779, he was appointed Minister to Spain, where he lobbied for diplomatic recognition and monetary support for the war. He occupied this role until 1782, when he was appointed Commissioner to treat with Great Britain to negotiate for peace. He spent several years in France and amongst other things played an integral role in the multi-party negotiations which led to the Treaty of Paris (1783), which officially ended the Revolutionary War. The treaty was well received at home.[5]

John Jay returned to New York City in 1784, and was appointed Secretary for Foreign Affairs.

John Jay was not a delegate to the Constitutional Convention which met in May 1787 in Philadelphia, because some voted against him on account of his known federalist views. But the drafters of the United States Constitution had before them John Jay’s New York Constitution. And he was a leading member of the New York Convention which ratified the United States Constitution in July 1788.

Further, between October 1787 and June 1788 a series of essays were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay and published in New York newspapers, anonymously, under the pseudonym “Publius”. They advocated the federalist case. The essays were also collected and published in two volumes as the “Federalist”. There were eighty-five essays in all. Most were authored by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Mr Jay wrote five. He might have played a larger role in that regard but for an injury – a stone had been thrown at his head at a riot which Mr Jay was trying to quell.

It has been said that “The essays became, for supporters, a Federalist bible” and “Perhaps no other single document best speaks in detail to the intention of the framers behind many of the concepts underlying the federal constitution”.[6]

As soon as he recovered from his injury, John Jay also published, anonymously, an “Address to the People of New York”, distributed in pamphlet form,[7] which advocated the Federalist case.

On 26 September 1789, President Washington appointed John Jay first Chief Justice of the United States, and he was confirmed, without objection, by the Senate.

In that role, he and Associate Justices also sat on federal Circuit Courts. The obligation of “riding circuit” was time consuming and burdensome. In those days travel was by horse drawn carriage, and Justices were required, since 1792, to rotate between Circuits, including Circuits that did not include their home States.[8]

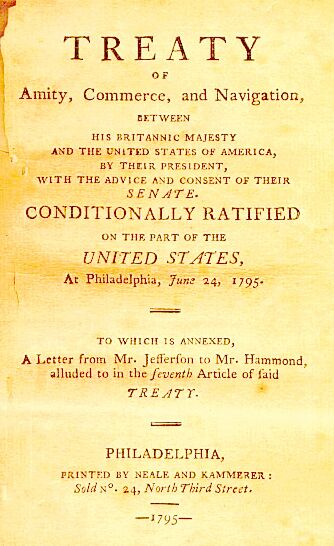

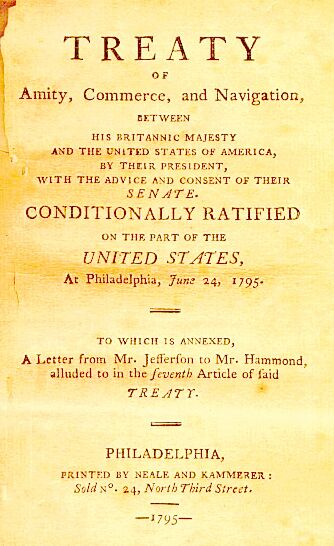

His judicial duties were interrupted by being called to serve as special envoy to Great Britain in 1794. He negotiated a treaty (commonly referred to since as the “Jay Treaty”) to settle issues remaining since the Treaty of Paris. The Treaty was ratified by the Senate in 1795. Despite that, it was not generally received well and, it is said, “very possibly” cost him the Presidency.[9]

The Jay Treaty

Mr Jay resigned as Chief Justice of the United States in 1795. He had been elected Governor of the State of New York. He was re-elected as Governor three years later. During his tenure, he played a pivotal role in the passage of an Emancipation Act in 1799 which law “set in motion the gradual ending of slavery within the state over a period of years”.[10] He did not stand in 1801 for a further term, and he retired from public life.

He declined an offer to nominate him for a second term as Chief Justice of the United States. John Marshall was nominated in his stead.[11]

Mr Jay died peacefully at Bedford, New York, on 17 May 1829, at the age of 83.

Jurist

In assessing the impact of Jay CJ as a jurist, it is not to be forgotten that his time as Chief Justice of the United States, like his time as New York Chief Justice, was interrupted by being called to serve in other ways including those mentioned above. That is not to say that his judicial output was insubstantial numerically – it was not.[12] It is not intended in this paper, nor is it feasible, to conduct a wide-ranging survey of the decisions of Jay CJ, whether sitting in the state or federal Supreme Courts or on circuit. But there are nevertheless some opinions of his which should be singled out as having had a particular impact in Australia.

…some opinions of his [Jay CJ] which should be singled out as having had a particular impact in Australia.

War Pensions

In 1792, the United States Congress enacted the Invalid Pensions Act which provided for pensions for war veterans who were placed on an approved pension list.[13] The Act conferred a jurisdiction on the Circuit Courts to decide if applicants should be placed on that list, which decision was reviewable by the Secretary of War and Congress.

On about 5 April 1792,[14] the Circuit Court for the District of New York, consisting of Jay CJ, Cushing J and Duane District Judge, unanimously agreed:[15]

“That by the constitution of the United States, the government thereof is divided into three distinct and independent branches, and that it is the duty of each to abstain from, and to oppose, encroachments on either. That neither the legislative nor the executive branches, can constitutionally assign to the judicial any duties, but such as are properly judicial, and to be performed in a judicial manner. That the duties assigned to the circuit, by this act, are not of that description, and that the act itself does not appear to contemplate them as such; inasmuch as it subjects the decisions of these courts, made pursuant to those duties, first to the consideration of and suspension of the secretary of war, and then to the revision of the legislature; whereas, by the constitution, neither the secretary of war, nor any other executive officer, nor even the legislature, are authorized to sit as a court of errors on the judicial acts or opinions of this court…”

They went on to consider whether they could act in persona designata.

Their Honours asked the Clerk of the Court to write to the President enclosing a copy of their observations, requesting that it be passed on to Congress. Subsequently, Jay CJ and Cushing J held the Circuit Courts for the Districts of Connecticut, Rhode Island and Vermont, together with the District Judges, and gave a similar opinion.

Thereafter, in April and June of 1792, Justices Wilson, Blair and Iredell et al made similar representations to the President, acting in the name of the Circuit Courts for the Districts of Pennsylvania and North Carolina, respectively.[16] Different views were expressed on whether the members of the Court could act in persona designata.

In August 1792, in Hayburn’s case, a motion came on before the Supreme Court of the United States for mandamus directed to the Circuit Court for the District of Pennsylvania compelling it to proceed in a certain petition for an invalid pension for William Hayburn. After hearing argument on the merits, the Court, Jay CJ presiding, adjourned the Court until the next term (February 1793). In the meantime, in February 1793 before the Court reconvened, Congress repealed and replaced the provisions considered unconstitutional, and otherwise provided for the relief of the pensioners.[17] No doubt the Court had given Congress that opportunity. The case was then dismissed as being purely academic.

But there had been cases where judges as commissioners had certified pending claims by applicants to be placed on the pension list under the 1792 Act. There was no decided Supreme Court decision that bound all Circuits. The 1793 Act indeed provided in s 3 that:

“But it shall be the duty of the Secretary of War, in conjunction with the Attorney General, to take such measures as may be necessary to obtain an adjudication of the Supreme Court of the United States, on the validity of any such rights claimed under the Act aforesaid, by the determination of certain persons styling themselves commissioners.”

In February 1794, the Supreme Court heard Ex Parte Chandler.[18] There, a veteran had been approved for a pension by the Eastern Circuit, but his name was not included in the pension list. John Chandler applied to the Supreme Court by writ of mandamus to compel the Secretary of War to place his name on the list. The Supreme Court, including Jay CJ, denied the writ by oral decision. There is no record of the reasons. It has been surmised, with some force, that the Court considered that the 1792 Act was unconstitutional and that the approval by the Eastern Circuit of Mr Chandler’s application was accordingly null and void.[19]

Also in February 1794, the Supreme Court, Jay CJ presiding, held that the United States could have restitution of a pension paid under the 1792 Act in an action for moneys had and received.[20]

Marshall CJ discussed the aforesaid events in Marbury v Madison, 5 US 137 (1803). The impact of that case in America and Australia needs no elaboration. In the course of upholding the principle of judicial review,[21] Marshall CJ observed at pp171-2:[22]

“This opinion seems not now, for the first time, to be taken up in this country.

It must be well recollected that in 1792, an act passed, directing the secretary at war to place on the pension list such disabled officers and soldiers as should be reported to him, by the circuit courts, which act, so far as the duty was imposed on the courts, was deemed unconstitutional; but some of the judges, thinking that the law might be executed by them in the character of commissioners, proceeded to act and to report in that character.

The law being deemed unconstitutional at the circuits, was repealed, and a different system established; but the question whether those persons, who had been reported by the judges, as commissioners, were entitled, in consequence of that report, to be placed on the pension list, was a legal question, properly determinable in the courts, although the act of placing such persons on the list was to be performed by the head of a department.

That this question might be properly settled, congress passed an act in February, 1793, making it the duty of the secretary of war, in conjunction with the attorney general, to take such measures, as might be necessary to obtain an adjudication of the supreme court of the United States on the validity of any such rights, claimed under the act aforesaid.

After the passage of this act, a mandamus was moved for, to be directed to the secretary at war, commanding him to place on the pension list, a person stating himself to be on the report of the judges.

There is, therefore, much reason to believe, that this mode of trying the legal right of the complainant, was deemed by the head of a department, and by the highest law officer of the United States, the most proper which could be selected for the purpose.

When the subject was brought before the court the decision was, not that mandamus would not lie to the head of a department, directing him to perform an act, enjoined by law, in the performance of which an individual had a vested interest; but that a mandamus ought not to issue in that case – the decision necessarily to be made if the report of the commissioners did not confer on the applicant a legal right.

The judgment in that case, is understood to have decided the merits of all claims of that description; and the persons on the report of the commissioners found it necessary to pursue the mode prescribed by the law subsequent to that which had been deemed unconstitutional, in order to place themselves on the pension list.

The doctrine, therefore, now advanced, is by no means a novel one.”

It should also be mentioned that the remonstrances of Jay CJ and the other Justices were referred to with approval by Dixon J in the important separation of powers case of Victorian Stevedoring and General Contracting Co Pty Ltd v Dignan (1931) 46 CLR 73 at p90.

The Treaty of Paris, by Benjamin West (1783) (Jay stands farthest to the left). The British delegation refused to pose for the painting, leaving it unfinished.

Chisholm

In 1793, a case came before the United States Supreme Court concerning whether an individual citizen of one State had a right to sue another State in that Court: Chisholm v Georgia, 2 US 419 (1793).

One Robert Farquhar had supplied cloth to the Continental Army in Georgia in 1777, for a price agreed with the authorised agent of the State of Georgia. Chisholm, Farquhar’s executor, sued Georgia invoking the original jurisdiction of the United States Supreme Court but the State of Georgia denied liability, maintaining that Georgia had sovereign immunity from suit.[23] Georgia refused to appear in the Supreme Court other than to demur to the jurisdiction.

By a 4:1 majority, the Court held that the State of Georgia was amenable to suit. The majority comprised Jay CJ, Blair, Wilson and Cushing JJ. Iredell J dissented. Each judge published a separate opinion. Opinions were given in reverse order of seniority, as was the custom at the time.

Article III § 2 of the United States Constitution provided relevantly that:

“The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority; – to all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consols; – to all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction; – to controversies to which the United States shall be a party; – to controversies between two or more States; between a State and citizens of another State; – between citizens of different States; – between citizens of the same State claiming lands under grants of different States, and between a State, or the citizens thereof, and foreign States, citizens or subjects.

In all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consols, and those in which a State shall be a party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction …” (emphasis added)

The reference to “State” first in the sequence before “citizens of another State” supported the view that the Constitution was only referring to cases where the State was plaintiff. This was consistent with the sovereign immunity argument in that the State would thereby consent to the jurisdiction of the Court. This view was consistent inter alia with statements made by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist Paper No. 81.

In rejecting that view, a common rebuttal in the opinions of the majority judges, was that the natural and plain reading of the wording included cases where the State was a defendant, relying on the fact that a State must necessarily be a defendant in the case of a controversy between two States. Jay CJ appealed to ordinary rules of construction, saying for example at p476 that “This extension of power is remedial, because it is to settle controversies. It is therefore, to be construed liberally”; and at p477, “Words are to be understood in their ordinary and common acceptation, and the word party being in common usage, applicable to both Plaintiff and Defendant, we cannot limit it to one of them in the present case”. It would have been easy for the framers to have said otherwise, if that had been their intention. Wilson J[24] remarked, citing Bracton, that it would be superfluous to provide a remedy without a right.

Jay CJ and Wilson J also pointed to other provisions in the Constitution where the exercise of federal legislative and executive power bound the States.

Jay CJ further appealed to the reasons inherent in a federation why the natural meaning should prevail, at p476:

“… in cases where some citizens of one State have demands against all the citizens of another State, the cause of liberty and the rights of men forbid, that the latter should be the sole Judges of the justice due to the [former]…”

He said similarly at p 474:

“Prior to the date of the Constitution, the people had not had any national tribunal to which they could resort for justice; the distribution of justice was then confined to State judicatories, in whose institution and organization the people of the other States had no participation, and over whom they had not the least control. There was then no general Court of appellate jurisdiction, by whom the errors of State Courts, affecting either the nation at large or the citizens of any other State, could be revised and corrected. Each State was obliged to acquiesce in the measure of justice which another State might yield to her, or to her citizens; and that even in cases where State considerations were not always favorable to the most exact measure. There was danger that from this source animosities would in time result; and as the transition from animosities to hostilities was in the history of independent States, a common tribunal for the termination of controversies became desirable, from motives both of justice and of policy.

Prior also to that period, the United States had, by taking a place among the nations of the earth, become amenable to the laws of nations; and it was their interest as well as their duty to provide, that those laws should be respected and obeyed; in their national character and capacity, the United States were responsible to foreign nations for the conduct of each State, relative to the law of nations, and the performance of treaties; and there the inexpediency of referring all such questions to State Courts, and particularly to the Courts of delinquent States became apparent. While all the States were bound to protect each, and the citizens of each, it was highly proper and reasonable, that they should be in a capacity, not only to cause justice to be done to each, and the citizens of each; but also to cause justice to be done by each, and the citizens of each; and that, not by violence and force, but in a stable, sedate and regular course of judicial procedure.”

Jay CJ also challenged the notion that the State of Georgia was a “sovereign State” for all purposes. He said:

“Prior to the revolution … All the people of the country were then, subjects of the King of Great Britain, and owed allegiance to him … They were in strict sense fellow subjects, and in a variety of respects one people. When the Revolution commenced, the patriots did not assert that only the same affinity and social connection subsisted between the people, of the colonies, which subsisted between the people of Gaul, Britain and Spain, while Roman provinces, viz. only that affinity and social connection which result from the mere circumstance of being governed by the same Prince; different ideas prevailed, and gave occasion to the Congress of 1774 and 1775. The Revolution, or rather the Declaration of Independence, found the people already united for general purposes, and at the same time providing for their more domestic concerns by State conventions, and other temporary arrangements. From the crown of Great Britain, the sovereignty of their country passed to the people of it … thirteen sovereignties were considered as emerged from the principles of the Revolution, combined with local convenience and considerations; the people nevertheless continued to consider themselves, in a national point of view, as one people …”

Although he (like Wilson J) advanced a notion of popular sovereignty, the underlying point was that the people were, first and foremost, Americans.

Jay CJ also denied that suability was incompatible with sovereignty, and appealed to general principles of justice and equality, for example:

“The only remnant of objection therefore that remains is, that the State is not bound to appear and answer as a Defendant at the suit of an individual: but why it is unreasonable that she should be so bound is hard to conjecture. That rule is said to be a bad one, which does not work both ways…”

And that:

“[The decision of the Court] provides for doing justice without respect of persons, and by securing individual citizens, as well as States, in their respective rights, performs the promise which every free Government makes to every free citizen, of equal justice and protection…”

Portrait of John Jay by Gilbert Stuart, 1794

The Court held that default judgment should be entered against the State of Georgia. But the judgment was not enforced.[25] Georgia passed legislation making it an offence to enforce the judgment, or bring similar claims against the State, punishable by death. This stalemate might be thought to reinforce the point made by Jay CJ about the need for an independent national tribunal with power to quell controversies between States, or between a State and a citizen of another State.

Ultimately, the Eleventh Amendment was passed, ratified in 1795. It provided that:

“The judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by citizens of another State, or by citizens or subjects of any foreign State.”

The United States Supreme Court has since rejected the reasoning in Chisholm, by a 5:4 majority, subject to a vigorous dissent.[26]

But much of the reasoning in Chisholm remains apposite to our own federation.

During the nineteenth century, Chisholm entered the Australian legal lexicon.

Chancellor Kent discussed Chisholm in the first volume of his renowned Commentaries on American Law published in 1826.[27]

Chisholm was referred to by Sir Isaac Isaacs at the Melbourne Convention in 1898.[28]

In their celebrated 1901 work, Quick and Garran referred to Chisolm in their discussion of s 75(iv) of the Australian Constitution.[29]

Sections 75 and 76 of the Australian Constitution provide:

“75. Original jurisdiction of High Court

In all matters:

- arising under any treaty;

- affecting consuls or other representatives of other countries;

- in which the Commonwealth, or a person suing or being sued on behalf of the Commonwealth, is a party;

- between States, or between residents of different States, or between a State and a resident of another State;

- in which a writ of Mandamus or prohibition or an injunction is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth;

the High Court shall have original jurisdiction. (emphasis added)

76. Additional original jurisdiction

The Parliament may make laws conferring original jurisdiction on the High Court in any matter:

- arising under this Constitution, or involving its interpretation;

- arising under any laws made by the Parliament;

- of Admiralty and maritime jurisdiction;

- relating to the same subject-matter claimed under the laws of different States.”

In Australia, the trend of judicial opinion is to affirm jurisdiction under relevant clauses of ss 75 and 76 exercised against States without their consent: see eg South Australia v Victoria (1911) 12 CLR 667;[30] The Commonwealth v New South Wales (1923) 32 CLR 200;[31] New South Wales v Bardolph (1934) 52 CLR 455, 459; The Commonwealth v Mewett (1997) 191 CLR 471 (Gummow and Kirby JJ, Brennan CJ agreeing); British American Tobacco Australia Ltd v WA (2003) 217 CLR 30.

Chisholm v Georgia was not mentioned explicitly in the judgments in those cases. But they were mostly cases where a State was sued by the Commonwealth or another State, or arising under s 76(i). So those cases did not require a decision under the limb of s 75(iv) that refers to matters between a State and a resident of another State. In Bardolph, which did arise under that limb of s 75(iv), it appears that sovereign immunity was not in contention and the Court just needed to be satisfied about its own jurisdiction.

Section 78 of the Constitution also should be noted. It provides:

“The Parliament may make laws conferring rights to proceed against the Commonwealth or a State in respect of matters within the limits of the judicial power.”

That power has since been exercised.[32] During the Melbourne Convention in 1898, Sir Isaac Isaacs argued that the mere conferral of jurisdiction in the Constitution was enough to curtail sovereign immunity.[33] This view did not, admittedly, command universal assent, and Mr O’Connor moved an amendment which led to the insertion of what is now s 78. But it is difficult to assert that the insertion of s 78 was indicative of unanimity amongst the delegates that legislation was needed to curtail sovereign immunity. Indeed, the prevailing view in the High Court is now that s 78 was not necessary in cases falling within s 75 (as opposed to ss 76 and 77): The Commonwealth v New South Wales (1923) 32 CLR 200, 207, 214-5; British American Tobacco Australia Ltd v WA (2003) 217 CLR 30 [15]-[16], [18] (per Gleeson CJ), [59]-[60] (per McHugh, Gummow & Hayne JJ; see also The Commonwealth v Mewett (1997) 191 CLR 471, 551 (per Gummow and Kirby JJ, with whom Brennan CJ agreed at 491, but see Dawson J at 496-7).

The United States Supreme Court has since rejected the reasoning in Chisholm, by a 5:4 majority, subject to a vigorous dissent.

Importantly, for present purposes, Isaacs J was a member of the High Court in The Commonwealth v New South Wales, decided in 1923. There, the question was whether Commonwealth could bring action against the State of New South Wales in tort in the High Court under s 75(iii), without the consent of the State. Knox CJ, Isaacs, Higgins, Rich and Starke JJ held that the Commonwealth could. Chisholm was cited to the Court in the course of argument.[34]

In joint reasons, Isaacs, Rich and Starke JJ said at pp 208-209 of 32 CLR 200:

“It may be convenient to refer first to the assertion (which is at the root of the defendant’s contention) that an Australian State is a ‘sovereign State’. Learned counsel placed the matter on the same plane as a foreign independent State, the ‘representative’ of which is included in sub-sec. II. of sec. 75. As to such a representative it was said the consent of the foreign State was necessary, and so of an Australian State. There are two fallacies involved in this. The first is that there is any analogy whatever between the position of the ‘representative’ of a foreign State and that of one of the States of Australia … what possible analogy is there between such a case – where person and property are judicially deemed to be outside the territory and beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the local Courts – and the case of an Australian State, an integral and necessary part of the territory of the Commonwealth in relation to this Court? New South Wales is not a foreign country. The people of New South Wales are not, as are, for instance, the people of France, a distinct and separate people from the people of Australia. The Commonwealth includes the people of New South Wales as they are united with their fellow Australians as one people for the higher purposes of common citizenship, as created by the Constitution. When the Commonwealth is present in Court as a party, the people of New South Wales cannot be absent. It is only where the limits of the wider citizenship end that the separateness of the people of a State as a political organism can exist…

The second fallacy in the defendant’s argument is in the use of the expression ‘sovereign State’ in relation to a State of Australia. Before the great struggle of the American Union for existence, costing uncounted lives and treasure, that expression was not uncommon in the United States. And that, despite the warning given by Story J. in his work on the Constitution. He says:- ‘In the first place, antecedent to the Declaration of Independence none of the Colonies were, or pretended to be, sovereign States, in the sense in which the term sovereign is sometimes applied to States. The term sovereign or sovereignty is used in different senses, which often leads to a confusion of ideas, and sometimes to very mischievous and unfounded conclusions.’ (par. 207). The conclusion to which we were invited to come in interpreting the Constitution upon the assumption that New South Wales is a ‘sovereign State’ would be both mischievous and unfounded. The term ‘sovereign State’ as applied to constituent States is not strictly correct even in America since the severance from Great Britain (see Story, par. 208). Still further from the truth is it in Australia…”

Story at those paragraphs refers to the Chisholm case in footnotes.[35]

Isaacs, Rich and Starke JJ went on (at pp210-1 and 213) to rely on the plain and literal reading of s 75.

Their Honours further referred at p214 to the principle of “equal and undiscriminating responsibility to obey the law or make reparation”, and noted at p215:

“As to all cases of controversies in which there might be the element of conflicting interests politically considered, an opportunity was definitely created of invoking the jurisdiction of a tribunal independent of any State …”.

By such reasoning, their Honours followed a similar path to Chisholm.

Their Honours cited Farnell v Bowman (1887) 12 App Cas 643. There, the Privy Council held that the New South Wales Claims against the Colonial Government Act of 1876 (39 Vict. No 38) curtailed sovereign immunity from suit, according to its plain meaning.[36] Farnell has since been described as “epochal” and “cataclysmic”.[37] But it was not the first case to conclude that sovereign immunity from suit had been curtailed. Chisholm v Georgia had decided as much nearly a century earlier.

Conclusion

John Jay’s contribution as a Statesman to the establishment of the United States was monumental. His contribution, particularly as a jurist, has not received the attention it deserves in Australia, which is perhaps not surprising because his time on the Bench was interrupted by other governmental duties. But in his judicial duties his work has had a significant impact including in Australia. His views on the separation of powers have been cited by Dixon J, and relied on in the oft cited case of Marbury v Madison. Indeed, the Hayburn and Chandler litigation set the scene for Marbury v Madison concerning judicial review of executive and legislative action. Further, in the writer’s view, Chisholm, including Jay CJ’s reasoning, shone a light on the path which would later be followed by the High Court of Australia.

[1] The factual background herein draws heavily on George Pellow, Making of Modern Law (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co 1898).

[2] Whom Jay would later run against, and defeat, in the race for Governor of New York in 1798: Mark Dillon, The First Chief Justice: John Jay and the Struggle of a New Nation, pp39-240 (SUNY 2022).

[3] For further reading on his pupillage and his substantial trial experience, see eg Dillon, supra n 2, pp6-18.

[4] An account of his work as Chief Justice is given at Dillon, supra n 2, pp34-5.

[5] Dillon, supra n 2 at p43.

[6] Dillon, supra n 2 pp47, 48.

[7] Making of Modern Law, supra, pp229-230.

[8] Circuit Courts at that time had original as well as appellate jurisdiction (from District Courts).

[9] Dillon, supra n 2, pp52-3, 58-5; Making of Modern Law, supra, p283.

[10] Dillon, supra n 2, p241.

[11] Dillon, supra n 2, p243.

[12] For further reading on his judicial activity, see Dillon, supra n 2, pp34-5, 52-3, 61-5, 71-195, 215-224.

[13] 1 Statutes at Large p243.

[14] The note to Hayburn’s Case, 2 US 408, 410 (1792) must be mistaken when it says the opinion was on 5 April 1791, as that would have been before the Act was enacted.

[15] Note to Hayburn’s Case, 2 US 408, 410-411 (1792).

[16] Ibid.

[17] 1 Statutes at Large, p324.

[18] The case is unreported. For further reading, see Dillon, supra n 2, pp91-111 esp at pp109, 111.

[19] Dillon, supra n 2, pp109, 111. But contra, David Miller, “Some Early Cases in the Supreme Court of the United States”, 8:2 Virginia Law Review pp108-120 (1921).

[20] United States v Todd, 13 How, 52, note.

[21] The Court held that William Marbury was entitled in principle to a writ of mandamus against the Secretary of State compelling the latter to deliver up a commission, but that the Supreme Court could not issue that writ in its original jurisdiction as the Constitution only conferred appellate jurisdiction on the Supreme Court in the present kind of case. The Act of Congress which purported to confer such original jurisdiction on the Supreme Court was to that extent unconstitutional and invalid.

[22] Chandler’s case was cited in argument at p149.

[23] Chisholm had previously sued, unsuccessfully, in the Southern Circuit Court, in Georgia. The Court was comprised of Iredell J and Pendleton District Court Judge.

[24] A member of the Constitutional Convention which framed the Constitution.

[25] Georgia later changed its mind and paid the judgment in 1847: see Dillon, supra n 2, p130.

[26] See Alden v Maine, 527 US 706 (1999).

[27] James Kent, Commentaries on American Law, vol. 1, Lecture XIV, p278 (1826).

[28] Convention Debates (Melbourne 1898) p1675.

[29] Quick and Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, §324, p 774 (1901, reprinted by Legal Books 1976).

[30] The Court comprised Griffth CJ, Barton, O’Connor, Isaacs and Higgins.

[31] The Court comprised Knox CJ, Isaacs, Higgins, Rich and Starke JJ.

[32] See Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth), s 64, if not also s 58.

[33] Convention Debates (Melbourne 1898) p1675.

[34] (1923) 32 CLR 300, 201.

[35] Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, Book II, §§207, 208, 4th ed (Boston: Little Brown & Co 1873). See also at §178. And see §216 of the first edition (1833).

[36] Affirming Bowman v Farnell (1886) 7 NSWLR 1 (Faucett and Windeyer J, Martin CJ dissenting).

[37] Downs v Williams (1971) 126 CLR 61, 80 (per Windeyer J).

Jay’s childhood home in Rye, New York

Jay’s childhood home in Rye, New York

The Jay Treaty

The Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Paris, by Benjamin West (1783) (Jay stands farthest to the left). The British delegation refused to pose for the painting, leaving it unfinished.

The Treaty of Paris, by Benjamin West (1783) (Jay stands farthest to the left). The British delegation refused to pose for the painting, leaving it unfinished.

Portrait of John Jay by Gilbert Stuart, 1794

Portrait of John Jay by Gilbert Stuart, 1794