FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 100: June 2025, Reviews and the Arts

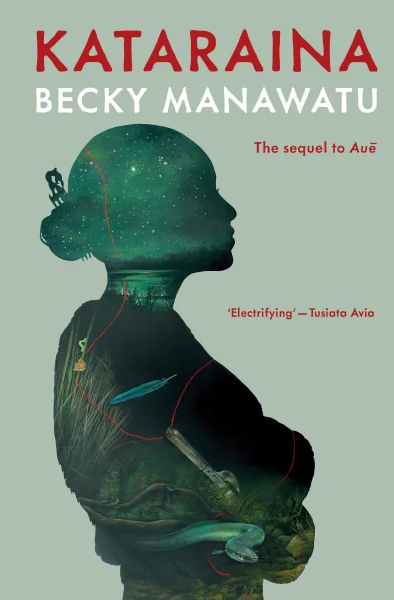

Author: Becky ManawatuPublisher: Scribe PublicationsReviewer: Stephen Keim

Kataraina is a sequel to Becky Manawatu’s Aue. Aue is centred on the story of Taukiri and his nine years younger cousin/brother, Arama, and Taukiri’s mother, Jade. Taukiri’s father, Toko, was murdered in a gang related crime in 2005 when Taukiri was four years old.

Arama goes to live with their aunt, Kataraina and her husband, Stuart Johnson, in a household that is dominated by Stuart’s violent and dominating personality.

Aue won Aotearoa New Zealand’s top prize for fiction and an international prize for crime fiction. Reviews of Aue indicate that the book raised controversy about its discussion of gang violence among Maori communities and brought comparisons to Keri Hulme’s 1984 novel, The Bone People and Alan Duff’s 1990 novel, Once Were Warriors.

Aue was also published in Australia by Scribe. Scribe has, as part of its business plan, a policy of obtaining the Australian rights to great writing published elsewhere in the world and, by republishing in Australia, bringing that literature to a greater collection of Australian readers. It has done so with Kataraina.

Kataraina is not a sequel in the sense that a sequel commences at the point where the narrative of the previous work finished. Kataraina works the same generational timeline as Aue. Kataraina changes the focus of the narrative. The blurb on the back cover of Kataraina describes Aunty Kat as being at the centre of events in Aue but silenced by abuse such that her voice was absent from the story. Kataraina, by contrast, is, primarily, her story.

Kataraina is told in the first person plural. The narrators appear to include all of the surviving members of the family and, perhaps, one or two important friends. The composition of the group narrator shifts from scene to scene depending on which of the collective are present and privy to that part of the story.

The complexity of telling an intergenerational story is acknowledged by a partial genealogy/family tree at the beginning of the book. A reader who, like this reviewer, has not read Aue finds themselves turning back to this guiding diagram, many times, in the opening chapters to remind themselves who, exactly, Granny Liz, Grandpa Jack, Jade, Toko, Aroha, Taukiri and Arama are.

The dramatis personae complexity is matched by the chronological complexity of the narration. The key event of Kataraina is an event at the end of 2017 when “the girl shot the man”. One finds out early in the novel that this event was the shooting of Kataraina’s husband, Stuart Johnson by Arama’s good friend, seven year old, Beth Aiken. The context of that shooting emerges slowly as the narrative jumps forward and back. The reader travels back to thirty-seven years before the girl shot the man as the story of Kataraina’s birth and her enduring importance to Granny Liz and her husband, Jack and their relationship is revealed.

The narrative also starts and finishes with “many years after the girl shot the man”, the latter chapter bringing a denouement in which the various actors have found a form of resolution and self-understanding to their relationships and trauma filled lives.

A second narrative (twisted around the story of Kataraina’s life and experiences) involves a day by day description of the work taking place in January 2020 of a scientific study group researching the dynamics of Johnson’s Swamp which, two years earlier, after being drained and confined for more than two centuries, has embarked on a massive expansion reclaiming its pre-colonial boundaries. One member of the study group, Cairo, is also related to Kataraina and her family’s principal actors of the main narrative.

A third narrative is foreshadowed in short enigmatic lines that appear between some of the chapters developing the main narrative. It is of an ancestor young woman who was first offered food in the form of peaches from a newly opened can and then attacked by a white colonist. The genealogy at the beginning of the book reveals an ancestor, Tikumu, who died in 1890. Cairo’s scientific team are party to discovering Tikumu’s story. Tikumu’s story plays a role in everyone’s attempts to find understanding and resolution.

Kataraina is set in Kaikoura, a coastal town on the northern part of the east coast of South Island. It is a fishing town. Kataraina draws on Maori lore and magic. A water spirit, a taniwha, plays an important role in the novel, assisting, advising and informing Kataraina at important times in her life. A glossary of Maori terms appears at the end of the book. Again, as with the genealogy at the front, the reader, regularly, turns to the glossary to feel the full power of the writing.

Kataraina’s story includes a youth of academic promise foiled by experiences in respect of which she had little control but for which she blamed herself. Her sense of shame and lack of self-worth led to a life of bad choices. She continued to blame herself for the unkindnesses piled upon her by her violent husband. The reader while not sharing Kataraina’s harshness on herself, nonetheless, is also able to understand Stuart and his self-experiences which led him to wreak pain and misery upon himself and those with whom he came into contact, including, most particularly, Kataraina.

Kataraina asks to understand the lives of others and to avoid blaming people for the misfortunes to which they are subject. Kataraina also invites us to understand the importance of love and friendship. It stresses the importance of understanding ourselves and others. It stresses the importance of hope among our sadnesses.

Kataraina is beautifully written. The complexity of the structure and the chronology is belied by the clarity of the writing. Descriptions of simple cooking producing delicious food bring colour and texture to lives of ordinary people. Descriptions of ordinary day clothes of people make the characters real enough that the reader can almost reach out and touch. The use of dialogue, extended at times, add to the reader’s sense of the relationships that are being portrayed. Kataraina also excels in describing the beauty of the Kaikoura landscape and wetlands. And, beyond portraying the scenes and sounds of everyday life, Kataraina also manages to convey the inner life of its characters especially Kataraina, herself. The combination of these traits makes reading Kataraina a joyful experience.

One of the joys of writing a review is that the reviewer is forced to return to the pages which, a short time ago, one has left with a sense of the achievement of having got to the book’s end. That sense of achievement may be tinged with a sense of melancholy in that a unique experience has come to an end. At other times, the tinge may be the colour of relief. Nonetheless, the sense of mission to understand the story and find out what happens, that every reader carries with them, causes us to miss the particular merits and beauty of the words we are reading along the way. We forget that what we can read in a few days or weeks has cost the writer years of careful craftmanship.

Having returned to Kataraina for this review, I have discovered a magical paragraph on the very first page about the importance of story telling. I leave you with Becky Manawatu’s words on that subject:

“Telling allows us to live in the plain and pointless space of proving the moving, flailing, contesting and yielding parts of a contradiction to all be true, or at the very least honest. Tika.[1] Pono.[2] Together we listen. One of us might sometimes create the scratch, whistle, scratch of lead on paper. Who even does that anymore. She does. Kataraina.”

[1] Correct

[2] Truth