FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 96: June 2024, Reviews and the Arts

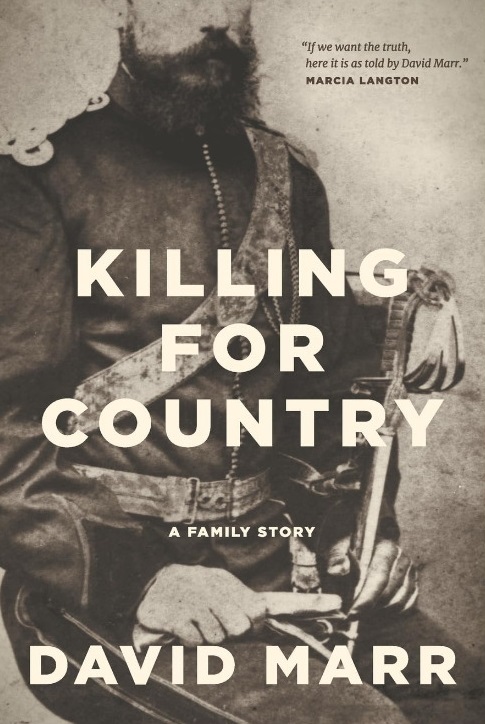

Author: David MarrPublisher: Black Inc.Reviewer: Stephen Keim

David Marr explains everything about Killing for Country in a note that occupies no more than one page and immediately follows the Contents page.

He says:

“I remember my great-grandmother. She had a crumpled face and faded away when I was too young to notice. She was a blank. Stories weren’t told about her. In 2019, an ancient uncle of mine asked me to find what I could about Maud. He knew so little. I dug out some books. It wasn’t long before I was looking at a photograph of her father in the uniform of the Native Police.

I was appalled and curious. I have been writing about the politics of race all my career. I know what side I’m on. Yet that afternoon I found in the lower branches of my family tree Sub-Inspector Reginald Uhr, a professional killer of Aborigines. Then I discovered his brother D’Arcy was also in the massacre business. Writing is my trade. I knew at once that I had to tell the story of my family’s bloody business with the Aboriginal people. That led me, step by step, into the history of the Native Police.

…”

The family story nature of Killing for Country is reflected in the three parts into which the book is divided: “Mr Jones”, “Edmund B. Uhr” and “Reg & D’Arcy”.

Richard Jones was a leading Sydney merchant who came to Sydney as a clerk in a merchant house in 1809. Jones returned to London in 1818 and conducted his various Australian enterprises from afar. In 1922, Jones married Mary Peterson. Jones was 36. Mary had five younger half-brothers named Uhr.

Marr describes the union between the pair, Jones and Peterson, as “unlikely” and the text does not explain how it came about. The effect was, however, that Edmund Uhr was “plucked from a poor street by the Thames” to drive and run expensive Saxony sheep for Jones, his half brother-in-law, initially, in the area of the Liverpool Plains.

In focussing the three parts of Killing for Country on individuals from, effectively, three generations, Marr covers a wide swathe of Australian history both in time and geography. Killing for Country is always about how the settler colonists killed the Indigenous people of Australia with great cruelty and in extraordinary numbers. It went on for a long time because pastoralists, in particular, were continually broadening their horizons by stealing new land and Jones and the two generations of Uhrs played very significant roles in that killing.

Killing for Country is, however, more than a family memoir. That tends to happen when the family story is told by one of Australia’s greatest documentary writers. Marr manages to tell the story of the four individuals. In covering those four lives, however, Marr also manages to tell a much broader story of the social and political context in which they lived. Jones’ early time in Sydney coincides with Macquarie’s governorship. The land being newly occupied by squatters and the resultant conflict with the Indigenous owners of the land and the resulting killing of those owners had moved beyond the immediate environs of Sydney but not by a huge distance. By the time the patchy careers of Reg and D’Arcy were coming to an end, the far north of Queensland and the top end of the Northern Territory had long been the subject of dispersion, a euphemism for killing, and dispossession, the whole point of the exercise. Killing had become industrialised for many years by then, primarily, through the use of the Native Police in which both Reg and D’Arcy had served as white officers.

In between, Jones and Edmund Uhr and others had shifted their focus to the Brisbane Valley, the Darling Downs, and coastal areas of Queensland such as Gympie and Maryborough.

The politics of dispossession were much fought over during the whole period covered by Killing for Country. Just as in modern settler colonial states, there was never any question that the settlers might not dispossess those to whom the land belonged. There was, however, even among the squatter class, the illusion of shades of opinion, a battle between moderates and radicals when it came to the killing. Some argued that the Indigenous former occupants should not be excluded from the new pastoral holdings but should be allowed to conduct aspects of their former lives and should be utilised as cheap and extremely competent labour on the holdings. Only the guilty, those who stole or attacked whites, these moderates argued, should be punished by being murdered.

Radical proponents of murder, however, argued that allowing any Indigenous person near towns or holdings was naïve and asking for trouble and would result in attacks on white people. Where crimes were committed, Indigenous people could only understand severe punishment and the best lessons involved massacres of whole communities including women, children and old people. If the alleged perpetrators of crimes were not part of the communities massacred, it mattered little since the lesson would be broadly learned and understood, in any event. And who, after the event, could say that the right people had not been killed?

These shades of opinion were reflected across the broader settler society. Governors tried, in accordance with their instructions from the colonial secretaries, to restrain the worst conduct of the squatters but tried not very hard. In any event, the rich merchants and squatters of which Jones was a member of both categories were, generally, at war with the governors, and had connections back in London with the use of whom they could conduct those wars. And colonial secretaries of a Whig persuasion tended to huff and puff about looking after the welfare of those whose land was being stolen but did so, ineffectively. Colonial secretaries of a Tory persuasion tended not to do much at all about the native question.

Marr’s treatment of the politics at the level of governors and colonial secretaries is assisted by his quoting of passages from their communications. My generation learned about the early governors of New South Wales in social studies in primary school. It was an important focus of the curriculum. What I learned, however, was little more than a list of names and a shorter list of bare facts. Killing for Country, in contrast, conveys a much deeper understanding of the early settler politics of New South Wales and Queensland than I have previously enjoyed. Marr manages to do this despite the narrow thematic focus of his subject.

In the same way, my primary and secondary education gave me a sense of the history of settler Australia that contained a huge black hole from the gold rushes of 1851 to federation in 1901. In covering the establishment of the Queensland Native Police and the conduct of that body over subsequent decades and the freelance killing conducted by squatters during the same period, Marr has also succeeded in conveying a vision of parliamentary politics and the personalities and styles of early Queensland politicians including a number of premiers.

Despite the failings of my schooling, in recent years, the efforts of historians and journalists like Marr had made me aware that the administration of justice had achieved something brave and wonderful in making murderers accountable for the slaughter of 22 Kamilaroi people at Myall Creek in the New England area in northern New South Wales. In reading Killing for Country, one is impressed both by how late and how early the Myall Creek events took place. The massacre occurred in June of 1838. For half a century, Indigenous people had been murdered in numbers before any settler was made accountable for such killing. Notwithstanding the convictions, another half a century and more of killing was to pass with Myall Creek becoming not the signifier of an era of even handed justice but, rather, the great anomaly of Australian history. The killing went on. The accountability died its own death.

The Myall Creek story recalls Marr’s dedication to those who told the truth. A station hand who alerted his supervisor; a squatter who alerted a police magistrate and then went on to Sydney to raise the alarm; that police magistrate who travelled to the site and actively investigated the crime and its perpetrators; and a Kamilaroi boy called Davy who hid behind the tree and witnessed the murders formed part of that crew. Davy’s evidence could not be received by the court because the law then stated that heathens, who had no fear of the eternal damnation promised by a Christian God, were not competent to testify in legal proceedings.

The success, and even the fact, of the prosecution was due in large part to the Irish lawyer, John Hubert Plunkett, who had, by this time, acceded to the post of Attorney-General of the colony of New South Wales. Plunkett with the support of the new governor, George Gipps, marshalled the available evidence into a powerful case for conviction. When, despite the quality and quantity of the evidence, the jury returned a not guilty verdict, Plunkett, forthwith, recharged 11 of the defendants with the death of four children who had also been killed in the massacre but were not the subject of the first set of charges. The result of the second trial was that seven of the perpetrators were convicted and, ultimately, hanged for the crimes.

But Myall Creek, despite Plunkett’s best efforts, was also flawed. A Gwydir squatter, John Fleming, had recruited twenty stockmen to ride on an expedition to find blacks to kill. The crime was particularly egregious because the group of Kamilaroi victims lived peaceably on another squatter’s property and had had nothing to do with any active resistance to the stealing of Kamilaroi land. They were killed, nonetheless.

Despite his organising and directing role in the slaughter, admissible evidence against Fleming was not available. He was not charged. Those who were on trial were successfully marshalled such that no one accepted the offered incentives to give evidence against Fleming and, thereby, save their own lives. Fleming was never made accountable. In the wake of Myall Creek, settlement continued to expand and, as the later chapters of Killing for Country graphically record, the killing only accelerated.

The acknowledgements section of most books I read are of much interest. They constitute a short-form version of the making of the Book. Killing for Country is a great work that was six years in the making. Its acknowledgements are particularly interesting.

At the front of the book, Marr’s dedication is “To those who told the truth”. On the following page, Marr writes: “I did not work alone. This book is the result of a deep collaboration over four years with my partner, Sebastian Tesoriero.” The story of the collaboration is told in more detail in the acknowledgements. In March 2020, Covid shut down the archives. It was at that point that Marr turned to Tesoriero, asking him to hunt for material online. Marr goes on: “[Tesoriero] has a lawyer’s mind and a hunger for facts. I knew he was a skilled internet sleuth. Trove opened its riches to him. As the year went by, we began working closely together and continued doing so until the end. He proved a fine-at times, savage-editor.”

Marr reveals the extraordinary amount of work done on the subject of the killing for country that took place in Australia. He, particularly, acknowledges Henry Reynolds and his 1981 work, The Other Side of the Frontier. Marr also mentions the wonderful poet, Judith Wright, as being the first person to make sense of this history through family memoir. The depth of research and search for understanding is illustrated by Marr’s heartfelt tribute to a series of local historical societies and local historians in the various parts of Australia covered by Killing for Country.

It would be remiss of me to conclude a review of Killing for Country or, indeed, any piece of writing by Marr without acknowledging the beautiful prose with which he delivers his narrative. Despite the meticulous research that has been undertaken by Marr, the learning and the references never get in the way of the narrative. The endnotes evidence the sources and verify the facts but one almost has to tear oneself away from the unfolding story to pursue one’s interest in a particular source.

Marr, as has been seen above, explains his family connection to the subject of Killing for Country and the questions it has raised for him as an active writer in the field of Australia’s colonial past and present. He then disappears from the page into the identity of the omniscient one. Marr returns to the page as the story reaches its conclusion and his precise connection with the protagonists is described.

The point is that nothing gets in the way of the story being told. The events are set out. The actors are introduced. They play the role in the events. The reader gets to know a lot about each person as their actions are unveiled. Personal foibles and shameful actions are acknowledged as they are conveyed. No time or space is wasted, however, on an excess of condemnation. For the plot is still unfolding and the rest of the story is still being told.

One approaches Killing for Country with caution. The reader knows that horrific events happened and those horrific events will be related without any lily being gilded or any sensibility being spared. Notwithstanding the horrific nature of the events, the reading of Killing for Country is a pleasure. The beauty of the prose and the fascinating quality of the narration ensures that that occurs.