Background

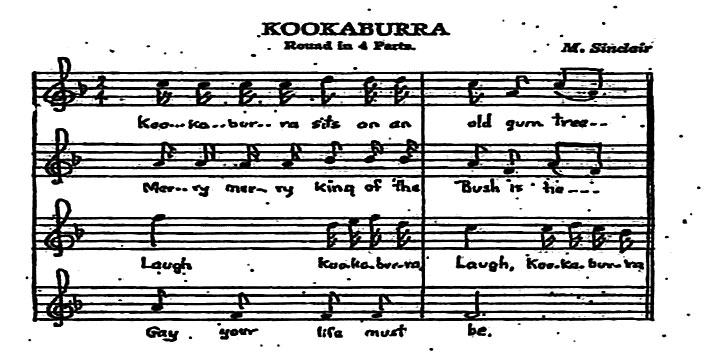

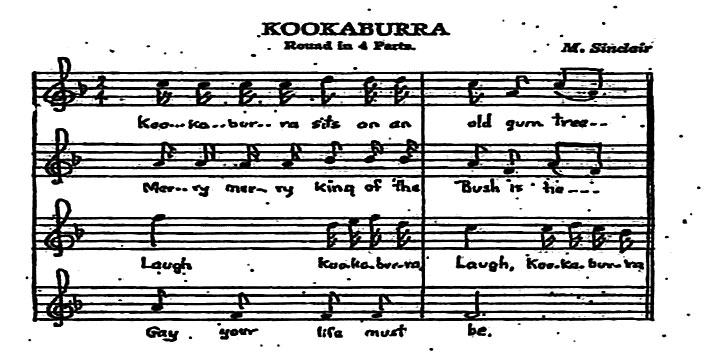

Ms Marion Sinclair composed Kookaburra in 1934, and the round became the winning entry in a competition organised by the Girl Guides Association of Victoria. Ms Sinclair died in 1988 and the Public Trustee was appointed trustee of her estate. The Libraries Board claimed ownership by virtue of a donation of records made by Ms Sinclair in 1987. Larrikin claimed to have acquired the copyright in Kookaburra from the Public Trustee or the Libraries Board or both. The decision on the Order 29 questions, affirmed Larrikin’s ownership: (see Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd v EMI Songs Australia Pty Limited [2009] FCA 799 (Jacobson J, 30 July 2009).

The second song, was the pop song known as Down Under, performed and recorded by the group Men at Work. Larrikin argued that the recording of Down Under made in 1981, as well as other associated works, including an early recording of the song, infringed copyright in Kookaburra. Specifically, two bars of Kookaburra were said to be reproduced in Down Under at various points through a flute riff played as follows:

- one bar (the second bar) of Kookaburra, immediately after the percussion introduction; and

- at two other points in Down Under, where the flute riff included both the first and second bar of Kookaburra

Relevantly, Kookaburra was analysed for the purpose of the proceeding as consisting of four musical bars. It should also be noted, that the flute riff contained other notes which were not part of Kookaburra.

Larrikin became aware in 2007 of the resemblance and brought its claim against the respondents. The respondents (conveniently EMI), comprised of two individuals, the composers of Down Under and former Men at Work members and two EMI corporate entities being the owner and licensee respectively of the copyright.

Issues

Leaving aside the question of causal connection which was not disputed, there were two principle issues:

- whether there was a sufficient degree of objective similarity between the flute riff in Down Under and the two bars in Kookaburra; and

- if there is such objective similarity, whether the two bars of Kookaburra were a substantial part of Kookaburra: [10] (S. W. Hart & Co Proprietary Limited v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 at 472): see s14 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

Decision

The 1979 and 1981 recordings of Down Under infringe Larrikin’s copyright in Kookaburra because both recordings reproduce a substantial part of Kookaburra: [337]

Reasons

The parties had sought the opinions of two experts as to the differences and/or similarities between the musical compositions. The musicologist called by Larrikin, was of the opinion that there was a difference in harmony between Down Under and Kookaburra. However, those differences were overshadowed by the melody of the flute riff when it played the first two bars of Kookaburra.

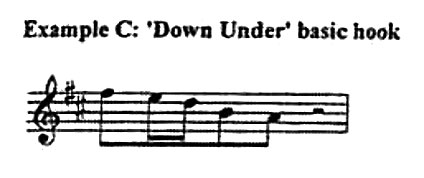

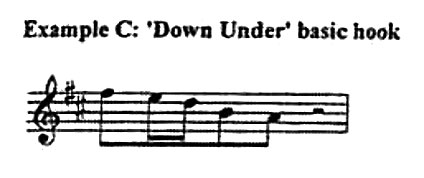

In considering these issues, the concept of musical ‘hooks’ was raised. This concept in popular music involved the introduction of a short musical instrumental infusion, which it was hoped would catch the ear of the listener, making the work memorable and recognisable, whenever the song was played. Larrikin’s evidence proceeded on the basis that those first two bars contained a musical hook. The hook, according to the Larrikin expert, appeared as follows in Down Under:

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

The expert called by EMI, in his affidavit evidence did not agree that the signature of Down Under was the flute riff. He opined, that the signature or hook of Down Under was the lyric ‘I come from a land down under’. However, in cross examination, he agreed that the first bar could be considered the signature of the song. The EMI expert, although acknowledging the ‘signature’ of the musical work could be the first bar, considered the argument centered around the issue of whether this bar or the first two bars, were a substantial part of Kookaburra.

Jacobson J considered the relevant decisions on the issue of substantiality and causal connection and distilled from them certain relevant principles from the issues to be determined in the case. These can be summarised:

- a sufficient degree of objective similarity is required between the two works: [33] (Francis Day & Hunter Ltd v Bron [1963] 1 Ch 587; S. W. Hart);

- there needs to be a causal connection between the conflicting works: [34] (Francis Day; S. W. Hart): [34] and that the causal connection which must be established is that the infringer copied the applicants work [49] (Francis Day on appeal)

- has the alleged infringer copied a substantial part of the copyright work: [35] (Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v William Hill (Football) Ltd [1964] 1 WLR 273);

- it is the particular form of expression which is to be protected: [40] (IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 254 ALR 386;

- the issue of substantial part is to be determined more by the quality than the quantity of what is copied: [42] (IceTV at [30], [155] and [170]);

- the causal connection which must be established is that the infringer copied the applicants work [49] (Francis Day Appeal)

- the more simple or lacking in substantial originality the copyright work, the greater will be the necessity to take a larger portion of it before a substantial part test is satisfied; [56] (IceTV)

Assessing infringement

His Honour considered that there were three steps in the comparison process. These were, firstly to identify the work in which the copyright subsists. Secondly, to identify in the allegedly infringing work, that part which is alleged to have been copied from the copyright work. Thirdly, to determine as to the part which was taken, whether that part was a substantial part of the copyright work:[60]. The copied features must therefore be a substantial part of the copyright work.

Identifying the work

The copyright work was the 1934 musical work of Miss Marion Sinclair, the successful entrant in the Guides’ competition, published by the Guides Association in their publication as “Three Rounds by Marion Sinclair” in the F key:

The offending part of Down Under

Down Under was written by Mr Hay and Mr Strykert in 1978 and recorded in 1979. The song did not originally contain the flute riff, however in the 1979 recording (where it was the B side of the record), an improvised flute solo (contributed by a Mr Ham), was added. It was Mr Hay’s evidence that he was not aware when the song was written or recorded of the reference to Kookaburra, but learned of it ‘some years ago’, but could not recall how he was made aware.

This 1979 version embodied the first four bars of Kookaburra (as they are shown above), and appeared just once in the song. A 1981 recording of Down Under appeared on the album entitled ‘Business as Usual’, an album which became a number one hit on the musical popularity charts of Australia, the UK and the USA. In this version of Down Under, the reference to Kookaburra appeared three times in various forms.

In cross examination, Mr Hay accepted that for approximately 2 or 3 years from 2002, he sometimes sang the words of Kookaburra during the song, when he performed Down Under at concerts.

The evolution of Down Under appears at [85] to [100].

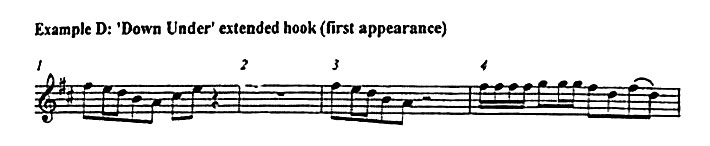

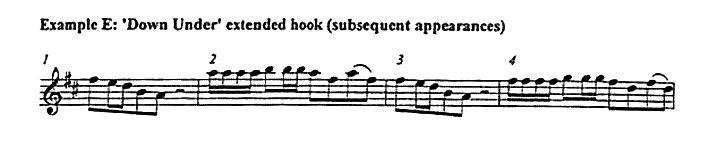

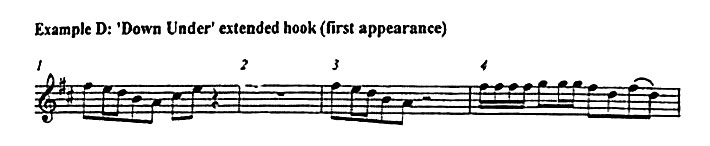

Relevantly, the expert evidence of Larrikin opined that the hook recurred throughout Down Under as both an embellishment to the accompaniment and also as one element in a longer four bar hook: [79]. The first appearance of the hook appeared as follows (in the key of D):

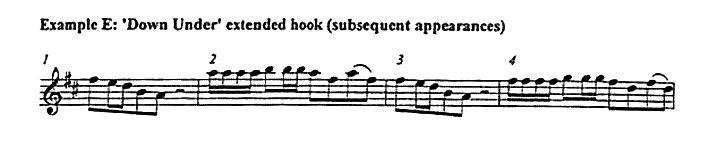

The first bar contains the basic hook with two additional notes (not appearing in Kookaburra); the second bar has music infill and the third bar contains the basic hook, while the fourth bar is the second phrase of Kookaburra. The subsequent appearances of the extended hook (also shown in the key of D) appeared as:

In this example, the first and third bars are the basic hook, while bars two and four, were opined to be direct quotes from Kookaburra. In Down Under, these phrases are played by the flute. In the opinion of the Larrikin expert, Down Under could be broken down as follows:

1 bar: Percussive intro

4 bars: Hook (Example D — 4th bar contains 2nd phrase of ‘Kookaburra’)

8 bars:Verse

8 bars: Chorus

4 bars: Hook (Example E — 2nd bar contains 1st phrase of ‘Kookaburra’, 4th bar contains 2nd phrase)

8 bars: Verse

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Instrumental fill

4 bars: Hook (Example E — 2nd bar contains 1st phrase of ‘Kookaburra’, 4th bar contains 2nd phrase)

8 bars: Verse

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Chorus

8 bars: Chorus (fade begins)

EMI argued that the difference in the structure of Down Under from Kookaburra, together with the differences in melody, harmony and tempo, made it difficult to recognise Kookaburra in Down Under.

Was there substantial reproduction of Kookaburra?

Jacobson J found that in both a qualitative and quantitative sense, a substantial part of Kookaburra was reproduced in Down Under, notwithstanding that the reproduction did not correspond exactly to the phrases of Kookaburra because of the Down Under structure.

His Honour’s relevant findings

His Honour’s relevant findings

His Honour accepted the conclusion of the expert for Larrikin, that the quoted passages in Down Under were the same as the melodic phrases in Kookaburra: [178]. Jacobson J also accepted the evidence of the expert for Larrikin, that the melody was tempo of Down Under was ‘more or less’ the same as one would sing Kookaburra.

The EMI expert had placed emphasis on the melodic difference between Kookaburra and Down Under. The basis of this opinion, was the harmonisation in Down Under from a major key to its relative minor key. His Honour was of the view, that the shift in harmony, did not make the Kookaburra phrases unrecogniseable: [189].

Jacobson J observed however, that whilst the EMI expert placed emphasis on the differing structures, in cross examination, he agreed with the Larrikin expert, that the call and response were a merged musical statement and that the notes from Kookaburra ‘played an important, indeed essential function’ in the flute riff.

Senior Counsel for EMI posed the question, that if Kookaburra and Down Under were both iconic Australian tunes with strong similarities, why it took so long to recognize the similarity. In this context, reference was made to the television show Spicks and Specks which exposed the similarity. His Honoue considered that the television show indicated that despite difficulties in the recognition of the connection, a ‘sensitised listener’ could make the connection: [207].

Mr Ham, who was responsible for the injection of the flute riff in Down Under, said in his affidavit, that adding the flute line was designed to add an Australian flavor. Relevantly, Mr Ham was not called. His Honour considered that not only was he entitled to infer that the witness could not have assisted EMI’s case, but that Mr Ham deliberately reproduced a part of Kookaburra as part of the concept of adding an Australian flavour: [214].

His Honour found that the reproduction by Mr Ham of the relevant bars of Kookaburra, re-inforced his Honour’s finding on objective similarity. The failure to call Mr Ham underpinned this finding. In relation to Mr Hay, his Honour accepted that the taking of portions of Kookaburra was not known to Mr Hay until much later.

Damages

Jacobson J determined that although general damages were assessable under s 115(2) of the Copyright Act 1968, there was no evidence EMI knew let alone authorized the reproduction. Although, the claim might be made against Mr Hay, it did not appear to extend to EMI.

The claim made under the Trade Practices Act, namely that income received from royalties was based upon a misrepresentation that EMI was entitled to all of the income. His Honour determined that the EMI parties had misrepresented that they were entitled to 100% of the income paid by the collecting society, through its warranty in the exclusive licence with the society and its constitution.

APRA, the collecting society for performance rights, was not in the same position, as their payments were made in accordance with member notifications not based on actual ownership.

Jacobson J pointed out at [339], that the findings did not amount to a finding that the flute riff was a substantial part of Down Under nor that it was the “hook” of that song. Accordingly, the question of the percentage of income Larrikin ought to be paid, had not been determined by this hearing, but to be determined on other principles.

Conclusion

His Honour determined that the 1979 recording and the 1981 recording of Down Under infringed Larrikin’s copyright in Kookaburra because both of those recordings reproduced a substantial part of Kookaburra.

Jacobson J also determined that Larrikin was entitled to recover damages from EMI for the infringements under the Trade Practices Act or the Fair Trading Act. Once the infringements were accepted, recovery under s 82 of the Trade Practices Act and the corresponding provisions of the Fair Trading Act followed despite the EMI defences.

Comment

In relation to the finding of substantial reproduction, his Honour made a refreshingly practical observation. With reference to the use by Mr Hay at some performances of Kookaburra when performing Down Under in around 2002, his Honour said at [228]:

The reproduction did not completely correspond to the phrases of Kookaburra because of the separation to which I have referred. But Mr Hay’s performance of the words of Kookaburra shows that a substantial part was taken. (Underline added)

Dimitrios Eliades

Footnote

- Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd v EMI Songs Australia Pty Limited [2010] FCA 29 (Jacobson J, 4 February 2010)

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

It was reproduced at [78] of his Honour’s reasons.

His Honour’s relevant findings

His Honour’s relevant findings