Law not War: The Life of Benjamin B. Ferencz

Cutting a tiny figure in amongst people towering over him, Benjamin (Ben) Ferencz holds court before some 300+ competitors, coaches, and adjudicators. The room is full of excitement, not because it is the opening night of the 2017 International Criminal Court Moot Competition (‘ICC moot competition’), but because Ben Ferencz is there. He is charming and endearing and evidently kind – willing to meet and pose for photos with students.

I, however, had absolutely no idea who he was. My teammates were a tad horrified given where we were after all. I very quickly learned who Ben was and his association with international criminal law.

Ben was the last surviving prosecutor of the Nuremberg Trials. At the mere age of 25 years, Ben was tasked with the responsibility of investigating and collating the evidence. He later became the Chief Prosecutor on the Einsatzgruppen Trial. I will return to this shortly.

In 2017, Ben and his son travelled from the United States to The Hague, Netherlands to open the ICC moot competition and welcome those who were participating. The fact that the footpath next to the Peace Palace was being named Benjamin Ferenczpad (‘Benjamin Ferencz Path”) in his honour may also have been part of the reason for his trip. Though he had entered his 97th year when attending the ICC moot competition and he needed a little assistance with travelling – his incredibly sharp mind, intelligence, and wit remained untouched. His humour was infectious and upon getting a glance at our team’s coach, a well-known Brisbane Barrister and Academic, he promptly referred to him as Santa Claus – said with a cheeky grin and a laugh. That nickname stuck for the remainder of the competition.

In his plenary speech, Ben’s passion for justice and peace and his intrinsic value of leaving the world in a better place was obvious. He had the full attention of the auditorium. We hung onto his every word. He spoke of his time investigating the atrocities of war and that during the course of collating and in examining the evidence ahead of the Trials, he connected and identified the Nazi hierarchy that needed to be held liable and to account for the mass slaughters they were responsible for. Had he not made that connection the Trials may have been more problematic and one Trial would not have existed. Most of all, he inspired hope and he instilled faith. He reminded us of the responsibility that we, as lawyers (or law students at the time), have to contribute to making the world a better place. And with that the week-long competition commenced.

In 2020, Ben left the world with his Parting Words – 9 lessons for a remarkable life. This legacy – his book – gives us a personal glimpse into Ben’s remarkable life.

“His arrival into the US was ‘under false pretences: as a four-month-old baby girl …’”

Ben was born on 11 March 1920 in a historical region of Transylvania and as he says, his journey commenced in one of ‘absolute poverty’.[1] When he was nine months old, to avoid persecution of Hungarian Jews, his family emigrated to the United States of America (‘US’) settling in New York City. He says that his arrival into the US was ‘under false pretences: as a four-month-old baby girl’ as the immigration officer who processed his family’s arrival misheard the Yiddish name Berrel for Bella and upon looking into the cradle decided he was four months old.[2]

Given the circumstances of the day and due to the fact that his family did not speak English, Ben’s education got off to a slow start. He was later admitted to Harvard Law School, applying there only because he was told it was the best [law school].[3]

Towards the end of his years at Harvard, World War II (‘WWII’) broke out and he recalls spending his last two years at law school suffering from ‘the anticipation that I would have to leave at any moment’.[4] He later learned, by pure chance, a man in the conscription office had let Ben finish law school at the request of the Dean.[5] This was to the world’s benefit.

Ultimately, Ben did end up being drafted into the Army. He served with the 115th Triple-A Gun Battalion and he says he ‘survived the war by damn good luck. I was short and therefore had bullets going over my head.’[6] As WWII was coming to an end, Ben was transferred to the newly established war crimes branch under General George Patton. The Lt. Colonel who greeted Ben promptly asked him: ‘Tell me, Corporal, what is a war crime?’. Ben recounts that his ‘time had finally come.’[7]

In his book Ben outlines the very early investigative steps he took to seize evidence of those war crimes and of the ‘scenes of indescribable horror’ he witnessed.[8] I won’t say too much for those that have not yet read Parting Words and now wish to do so. Ben was later tasked with finding and collating the evidence to put on twelve trials at Nuremberg which were to deal with branches of German government and society: the doctors who performed medical experiments, the lawyers who perverted the law by convicting people for political purposes, the industrialists who provided funding to build the camps etc.[9]

“He reminded us of the responsibility that we, as lawyers (or law students at the time), have to contribute to making the world a better place.”

One day Ben was handed critical documents marked ‘top secret’.[10] From this and the evidence he had already collected, Ben convinced his General that another trial must be heard. He was told no other lawyers were available and the budget had been set. Ben suggested he could run that trial himself.[11] In 1947, Ben opened the biggest murder trial in history, the Einsatzgruppen trial having strategically and carefully selected just 22 out of 3,000 mass murderers to appear. He was just 27 years old, and it was his first-ever case.[12]

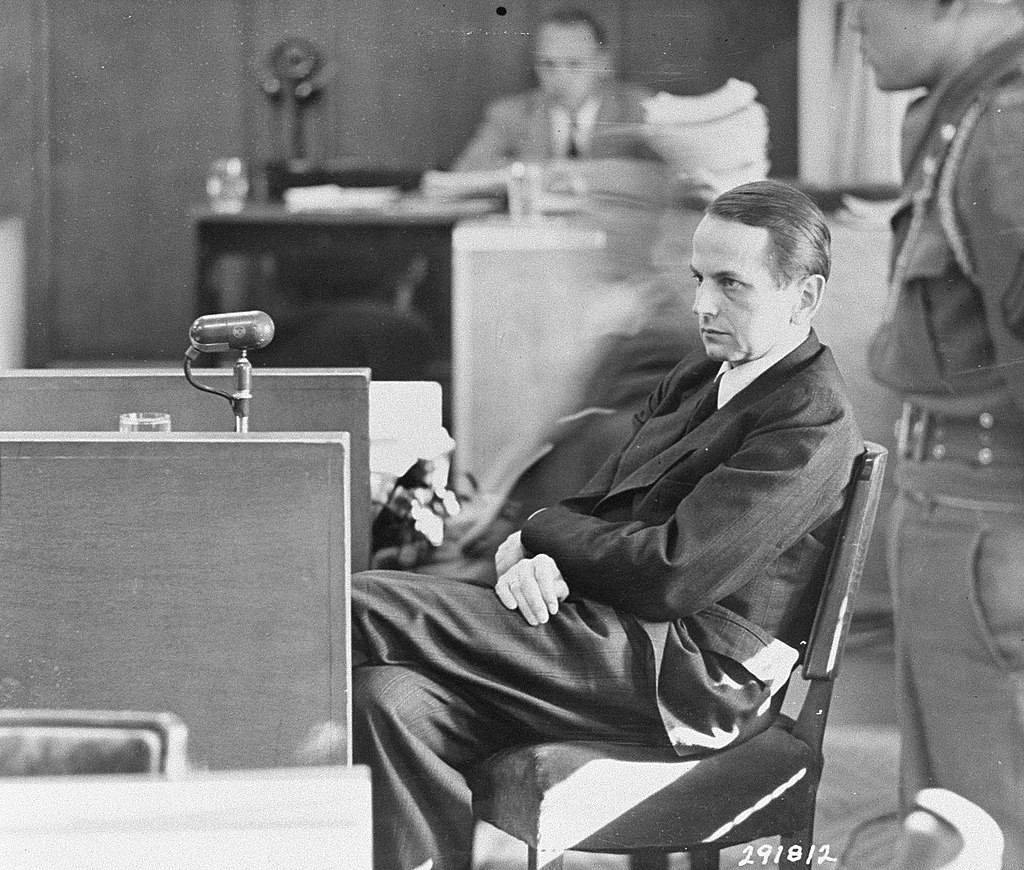

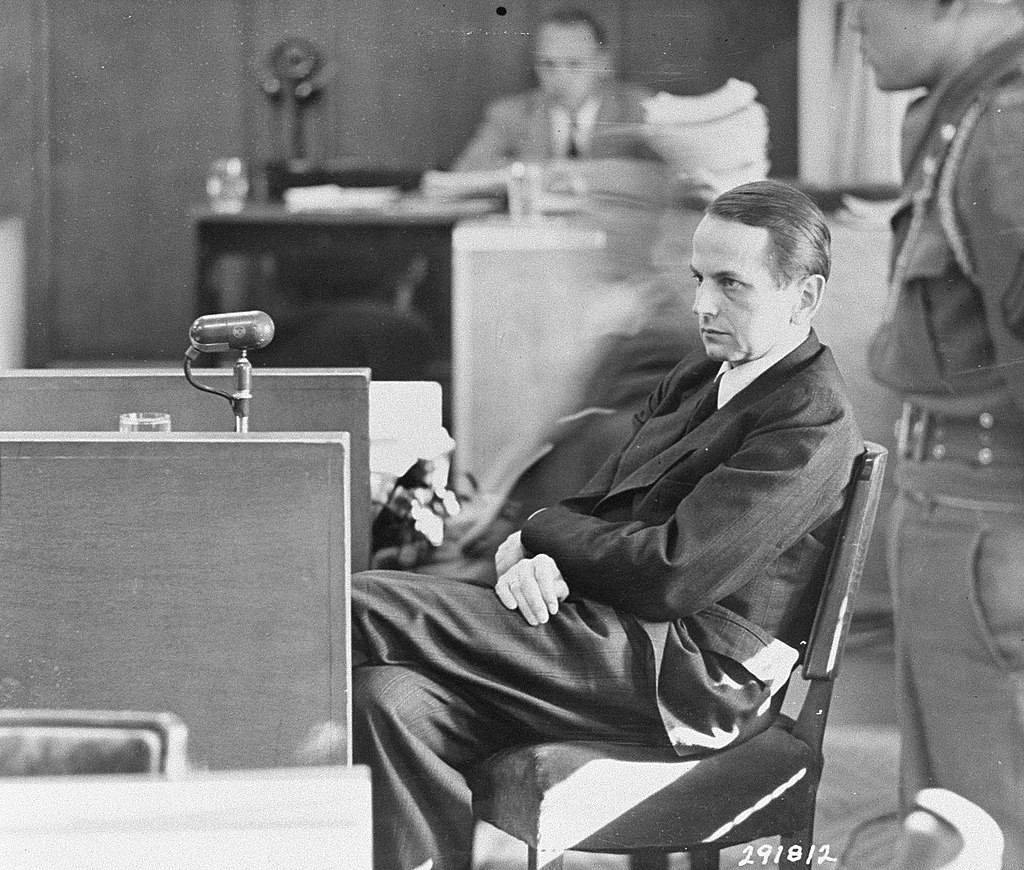

Chief defendant at the trials, Otto Ohlendorf, executed by hanging on 7 June 1951.

Ben was also the first person to ever utter the word ‘genocide’ in a courtroom. In a 2020 recorded conversation, he said that genocide was the most horrendous of crimes and given the scale of the mass murder that occurred during WWII what happened had to be ‘described in words which were special’.[13] He also said that the ‘biggest mass murder, biggest genocide of all is making war itself, it’s [war] got to become obsolete, it should no longer be an option…’.[14] More recently, Ben was ‘heartbroken’ to learn of the War in Ukraine.[15]

“Ben opened the biggest murder trial in history, the Einsatzgruppen trial having strategically and carefully selected just 22 out of 3,000 mass murderers to appear. He was just 27 years old, and it was his first-ever case.”

Post-Nuremberg Trials, Ben remained a staunch advocate for human rights – advocating for a more humane world. Ben led efforts in recovering unclaimed Jewish property for individual victims and was involved in reparation efforts for survivors of Nazi persecution, which he said was the greatest achievement of his career.[16] He was also instrumental in the creation of a permanent international criminal court and advocating for the US to sign the Rome Statute. He was a firm believer in the long-established rule of law that the ‘law must apply equally to everyone’. When the Rome Statute was ratified by 60 countries in 2002, the US was not one of them.[17]

Despite what he read, saw, and heard during and after WWII, it is incredible to consider how compassionate Ben remained and that he retained his sense of humour. Ben remained a fierce advocate for a better world.

In his book, Ben outlines his 9 overall lessons and then shares his many smaller lessons learned throughout his lifetime. There were many lessons that resonated with me throughout but in particular I wish to share the following three:

- ‘You don’t need to accept something is a truth just because a person in authority tells you it’s so.’

- ‘Everything is impossible until it’s done.’

- ‘Don’t let great men or women daunt you; choose to be inspired instead.’

Ben passed away on 7 April 2023. He is the epitome of leading a remarkable life and the world is a better place for it. It only seems fitting to conclude this tribute with Ben’s own words that he lived by: ‘never give up’ and ‘law not war’.

Vale Benjamin B. Ferencz.

[1] Benjamin Ferencz with Nadia Khomami, Parting Words – 9 lessons for a remarkable life (Sphere, 2020) at 17 (Parting Words).

[2] Above, at 18.

[3] Above, at 47.

[4] Above, at 56.

[5] Above, at 60.

[6] Above, at 117.

[7] Above, at 67.

[8] Above, at 74.

[9] Above, at 84-85.

[10] Above, at 85.

[11] Above, at 87.

[12] Above, at 87.

[13] Conversation with Benjamin Ferencz (Michael Scharf, ICC Moot Court Competition, 2020).

[14] Above.

[15] ‘I am heartbroken’: Last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor on war in Ukraine (CNN, 2022).

[16] Above, n 1, at 119-120.

[17] Above, n 1, 124.