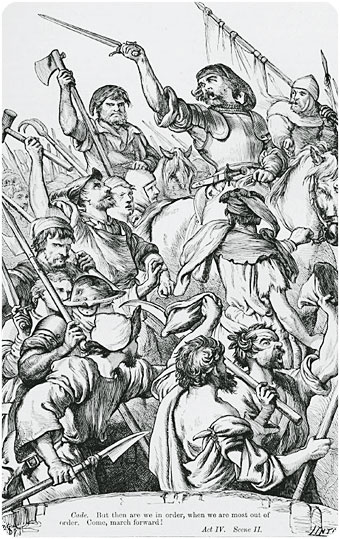

Although Shakespeare’s words have become a “rallying cry” for those indulging in the popular sport of lawyer bashing, some literature scholars have argued that their meaning is popularly misunderstood, and that Shakespeare was, in fact, not anti-lawyer. In 2006, the Supreme Court of Queensland held an exhibition entitled “Shakespeare and the Law” at which a banner “Shakespeare for Lawyers” was displayed. The banner offered this in the way of explanation:

“This remark was made by Dick the Butcher, a plotter of treachery in Shakespeare’s play Henry VI. Dick and John Cade are discussing how they will start the war and begin oppression of the people by taking away their property and individual liberty. Is this line proof that Shakespeare despised lawyers and the services they offer? Or was he aware that the surest way to chaos and tyranny in society was to remove the guardians of independent thinking – lawyers?”

That brings me to the central point of this paper, which is to submit that, like Shakespeare’s words, the impact of s 43 of the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal Act (“QCAT Act”) has been widely misunderstood amongst practitioners. Although the QCAT Act requires a party desiring legal representation to obtain leave, QCAT is not, as scuttlebutt suggests, a lawyer-free zone.

The QCAT Act states that in most cases, parties to a dispute are to represent themselves in proceedings before QCAT.1 Self-representation, unless the interests of justice require otherwise, is intended to ensure that QCAT proceedings are informal, economical and quick2 by encouraging the speedy resolution of disputes and minimising the costs incurred by parties. There are, however, circumstances where a party may be represented at a proceeding at QCAT. Even if a party is not able to be represented at a QCAT proceeding, they may still seek assistance from a lawyer regarding their rights, and in assisting with the drafting of any documents necessary for the proceeding.

For those practitioners who have thus far managed to avoid a round table discussion of the QCAT “lawyer filter” with colleagues, s 43 appears in the QCAT Act as follows:

Practitioners should also be aware of the impact of Part 7 “Provisions about parties to a proceeding” of the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal Rules 2009 (QCAT Rules). In particular, Division 1 of Part 7 relates to an “Appearance by a party that is not an individual or a group of applicants”. The purpose and explanation of Division 1, as set out in Rule 52, highlights a distinction between “representation” and “appearance”:

Rules 53 (“State agency”), 54 (“Corporation”) and 55 (“Other entity”) of the QCAT Rules permit employees, officers or members of those groups a right of appearance (on the conditions specified), but in each case, if a legal practitioner is seeking to appear, leave of the Tribunal must be obtained.

The net effect of Division 1, Part 7 of the QCAT Rules is that if a legal practitioner simply wants to appear on behalf of a party (e.g. State Agency in house team) all that is need is leave pursuant to Rule 53. Appearance pursuant to Rule 53 is not “representation”.

How does a party apply for legal representation?

Where a party is a child, a person of impaired capacity or a person facing disciplinary proceedings, that party is not required to apply to QCAT for permission to be represented as representation is a right under the QCAT Act.

In all other circumstances, a party wishing to be represented during a proceeding must make an application to QCAT using the form Application for leave to be represented. Although the form does not specifically state that submissions are required, it would be highly advisable to annex submissions addressing the factors contained in s 43 in more than cursory fashion. Failing to include submissions is likely to result in leave not being granted, particularly in circumstances where the opposing party asserts that they cannot afford legal representation. In Knight v Hansen [2010] QCAT 106, the applicant’s submissions in support of leave, prepared by his solicitors, consisted of the following 6 sentences:

“The matter has several complex legal issues involved. In terms of the prosecution of the matter it would be a simple case that the work was done and the Respondent failed to pay. From the Respondent’s documents it would appear that the issues become more clouded, particularly in terms of whether work was done to a competent standard. Our client is a pensioner with extremely limited legal understanding.

“The matter has several complex legal issues involved. In terms of the prosecution of the matter it would be a simple case that the work was done and the Respondent failed to pay. From the Respondent’s documents it would appear that the issues become more clouded, particularly in terms of whether work was done to a competent standard. Our client is a pensioner with extremely limited legal understanding.

The volume of material that is required to be put before the Tribunal is significant. It would be unjust to require our client to litigate this matter without any legal assistance.”

It was decided that these submissions did not sufficiently address the factors contained in s 43, in a manner sufficient to warrant the granting of leave. The respondent in Knight v Hansen did not intend to have representation, and did not consent to the applicant having legal representation. The submissions above fail to address the only remaining factor that would have entitled the applicant to obtain leave — that the matter was “likely to involve complex questions of fact or law” — in any meaningful way. The submissions simply present the conclusion, devoid of any explanation about the nature of the legal or factual complexity. Having found that the matter was a garden variety domestic building dispute, the request for leave for representation was denied.

Factors supporting the granting of leave

Factors supporting the granting of leave

Complexity

Some guidance on the general principles surrounding the granting (or denial) of leave can be found in the appellate decision of His Honour, Justice Alan Wilson, in Lida Build Pty Ltd v Miller [2010] QCAT 222 (“Lida”). In Lida, Member Peta Stilgoe, in determining the leave for representation application, found that the matter was not sufficiently complex to warrant the granting of leave. Lida involved the construction of a swimming pool, and in broad compass, variation claims, delay issues relating to a claim for liquidated damages, negligence, and unjust enrichment: Lida Build Pty Ltd v Miller [2010] QCAT 155.

In upholding Member Stilgoe’s decision denying leave for legal representation, Justice Wilson said:

It follows that nothing in the submissions delivered for Lida Build is persuasive that the learned member was wrong to conclude that the questions which might come before this Tribunal for adjudication ‘…necessitate input from a legal representative’. Subsequent submissions have the unfortunate effect of raising the spectre of the converse — that, in fact, the presence of lawyers may carry a risk of adding needless complexity, and much greater delay and cost, to what is essentially a simple dispute about the construction of a swimming pool and its surrounds.

Consent of the parties

It should be noted that whilst consent of the parties is one factor that QCAT will consider in support of the granting of leave for legal representation, it is not the only factor. Thus, practitioners should not assume, on the basis that they all consent, that QCAT will grant leave for legal representation without further consideration.

This is particularly so in circumstances where one of the parties consenting does so on the basis that whilst they do not object, they also do not intend to be represented. These circumstances presented in Lewis v Queensland Building Services Authority [2009] QCAT 041, wherein Mr Lewis consented to the Authority being legally represented on the basis that he himself was assisted by a non-legally trained friend. As Mr Lewis’s proposed “friend” for the purposes of legal assistance was not an Australian legal practitioner, and in the absence of any details as to the “friend’s” suitability, the “friend” was not considered to be an appropriate person to satisfy the conditions contained in s 43(4)(b) of the QCAT Act.

The matter involved an application by Mr Lewis to be categorised as a permitted individual for a relevant event within the meaning of s 56AD of the Queensland Building Services Authority Act 1991, with the potential to affect Mr Lewis’s ability to earn a living as a licensed contractor. Although the Member considered Mr Lewis’s consent to the Authority’s obtaining legal representation, it was found that it was not appropriate “to place the Applicant in a situation with there is an “information deficit” that he may not fully appreciate by granting the leave requested.” As such, despite the consent of the parties, and in consideration of the nature of the matter, an order was made in the following terms:

- In the event that the Applicant elects to be represented by an Australian legal practitioner, leave is granted for this purpose, and the Respondent is also granted leave to appear with legal representation. The Applicant is to notify the Respondent and the Tribunal of the name of any legal representative for these purposes on or before 4.00 pm on Friday, 22nd January 2010.

- In the event that the Applicant elects to represent himself in the matter, and does not notify the Respondent and Tribunal of the name of any legal representative for these purposes on or before 4.00 pm on Friday, 22nd January 2010, both parties are to represent themselves in the matter.

Cumulative effect of ss 3, 4 and 28 of the QCAT Act

The strength of an application for leave for representation in QCAT can be greatly enhanced by, in addition to addressing s 43 of the QCAT Act, addressing the objects3 and functions of the QCAT Act4. For example, submissions that illustrate the manner in which a legal representative may be able to encourage the early and economical resolution of a dispute, would be of assistance in supporting the granting the leave. In similar fashion, submissions that evidence an understand of the manner in which QCAT proceedings are to be conducted (focussing on the substantial merits of the case, without the strict procedural and evidentiary rules that apply in the courts5), will also aid the Tribunal in determining that leave for representative should be granted as it will help the Tribunal to act “fairly and according to the substantial merits of the case”. Said a different way, submissions that serve to complicate an otherwise uncomplicated proceeding, with technical arguments about evidence and procedure, may be seen to obfuscate QCAT’s overarching objectives.

Impact of s 29 QCAT Act

Impact of s 29 QCAT Act

Often, submissions in support of an application for leave for representation assert that without the benefit of legal assistance, a party will struggle to understand the process. However, the understanding, or lack thereof, of a party is not a factor that supports the granting of leave in the context of s 43. Rather, s 29 of the QCAT Act requires the Tribunal to take all reasonable steps to ensure that each party to a proceeding understands the practices and procedures of the Tribunal, the nature of assertions made in the proceeding and the legal implications of the assertions, and any decision of the Tribunal relating to the proceeding.

The distinction between s 29 and s 43 of the QCAT Act was explained in Additions Building v Keefe:

“There is no provision within s 43 of the QCAT Act entitling a party to be represented on the basis of the party’s feeling intimidated, or having a preference to remain represented.

Tribunal obligation to ensure party understands proceedings

There is nothing in the material before me that suggests that Ms Keefe is not capable of understanding the proceedings in this matter. That said, s 29 of the QCAT Act requires the Tribunal to take all reasonable steps to ensure that each party to a proceeding understands:

(i) the practices and procedures of the tribunal; and

(ii) the nature of assertions made in the proceeding and the legal implications of the assertions; and

(iii) any decision of the Tribunal relating to the proceeding.

Further, s29(1)(b) of the QCAT Act requires that the Tribunal take all reasonable steps to ensure that parties:

understand the actions, expressed views and assertions of a party to or witness in the proceeding, having regard to the party’s or witness’s age, any disability, and cultural, religious and socioeconomic background.

Thus, if it becomes apparent to the Tribunal during the hearing process that Ms Keefe’s apprehension about self-representation is attributable to any of the above mentioned factors, the Tribunal will take all reasonable steps to address the issues.”

Impact of legal representation on costs

Each party to a QCAT dispute bears its own costs,6 unless it in the interests of justice to have one party pay the costs of another.7 In deciding whether to award costs against a party, QCAT may consider a number of things, including:

- whether the party unnecessarily disadvantaged the other;

- the financial circumstances of the parties;

- the nature and complexity of the dispute;

- the relative strength of the claims made by the parties;

- anything else QCAT considers appropriate.

QCAT may also order that the representative, rather than the party, pay the costs of the opposing party. This may only occur if QCAT is satisfied that the representative, rather than the party, is responsible for unnecessarily disadvantaging the other party8.

Member Peta Stilgoe considered the impact of legal representation in the context of costs in her decision in Douglass v Hastie Building Group Pty Ltd [2010] QCAT 353 (“Douglass”):

“Section 100 of the QCAT Act provides that, other than as provided under this Act or an enabling Act, each party must bear their own costs. It is not in the interests of justice [section 43(1) of the QCAT Act] to have an order for compensation negated by the costs of obtaining that compensation. It is an emerging principle of modern jurisprudence that the effort required to achieve a result must be proportional to the result.9

The tribunal also has an obligation to ensure that the conduct of proceedings observes the principles of natural justice [section 28(3) of the QCAT Act]. Any resource imbalance between the parties will be a factor in the tribunal’s consideration of whether the conduct of the proceedings does comply with the principles of natural justice.

Neither party has made any submissions about the impact of costs in these proceedings. It is a significant and important issue, given that the monetary relief claimed is modest. I would not be inclined to grant leave for legal representation for the balance of the proceedings unless the parties address the tribunal on the issue of costs. If the dispute proceeds beyond 17 September 2010, both parties will need to make a fresh application for leave to be legally represented.”

For similar reasons, in Lowik v Carl Linklater Pty Ltd [2010] QCAT 287 (“Lowik”), the Tribunal determined that it was not necessary for the successful applicant to have an instructing solicitor plus a barrister. In her decision, the Member writes:

In my view, this was not a case that necessitated the appearance of both an instructing solicitor and barrister, and is the sort of case that could have been competently handled by the parties themselves, and certainly by a solitary advocate. Whilst I am not suggesting that Counsel does not have a welcome place in QCAT, in matters such as this which are not legally complex, in a jurisdiction that contemplates both self-representation and that parties bear their own costs, such decisions should be made carefully and with a modicum of “legal costs economy”.

For these reasons, the successful applicants in Lowik were awarded legal costs on the Magistrates Court Scale, but the Tribunal excluded the costs of having both an instructing solicitor and barrister appear at the hearing, and awarded the costs of one representative appearing only (whichever was the lesser).

So, where are all the lawyers?

So, where are all the lawyers?

Be assured that Justice Alan Wilson, the President of QCAT, is not a modern-day Oliver Cromwell. Those readers with a historical bent will recall seventeenth century England and Cromwell’s efforts to thwart individual freedoms, by decreeing that no more than three barristers could congregate outside of court. As you will recall, Lord Cromwell saw the commitment of the London Society of Barristers to the Magna Carta, as the greatest threat to his own tyrannical edicts.

However, here at QCAT, it can fairly be said that on most days, one could find more than three legal practitioners congregated on Level 10 of the Bank of Queensland Building, just prior to 9.30 am. One could be forgiven for perceiving the contrary, if one’s view was formulated based upon QCAT’s published decisions alone.

For the past several months, the practice at QCAT has been to provide written reasons, which are then published, only in cases where leave for legal representation is denied, or when a Member considers written reasons necessary for some other reason (such as in Douglass, where Member Stilgoe granted limited leave). Thus, in cases where leave is granted, written reasons are not routinely given, meaning that there is not a ready body of decisions that practitioners can look to for comfort.

Conclusion

QCAT welcomes the assistance of the legal profession in circumstances where the factors contained in s 43 of the QCAT Act are satisfied. In genuinely complex cases, or other cases where a party is entitled to representation as of right, the ability of a skilled advocate to assist the Member in understanding a party’s case is invaluable. QCAT routinely grants leave for representation in appropriate circumstances, but does not (unless requested) provide written reasons for doing so.

Practitioners seeking leave will assist QCAT in properly understanding the merits of their application for legal representation by addressing the factors contained in s 43 in comprehensive fashion.

Dr Bridget Cullen Mandikos, Member

Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal

43 Representation

43 Representation “The matter has several complex legal issues involved. In terms of the prosecution of the matter it would be a simple case that the work was done and the Respondent failed to pay. From the Respondent’s documents it would appear that the issues become more clouded, particularly in terms of whether work was done to a competent standard. Our client is a pensioner with extremely limited legal understanding.

“The matter has several complex legal issues involved. In terms of the prosecution of the matter it would be a simple case that the work was done and the Respondent failed to pay. From the Respondent’s documents it would appear that the issues become more clouded, particularly in terms of whether work was done to a competent standard. Our client is a pensioner with extremely limited legal understanding. Factors supporting the granting of leave

Factors supporting the granting of leave  Impact of s 29 QCAT Act

Impact of s 29 QCAT Act  So, where are all the lawyers?

So, where are all the lawyers?