FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 44 Articles, Issue 44: Oct 2010

Tributes to Lord Bingham of Cornhill have described him as the greatest judge of our time. These tributes do not rest simply on his holding the top three positions in the British legal hierarchy: Master of the Rolls, Lord Chief Justice and Senior Law Lord, something unparalleled in the modern era. They also rest on his contribution to the law and the assessment of contemporaries that he was one of the most brilliant and independent judges of his generation.

Tom Bingham was born in London in 1933, and after national service graduated with first class honours in modern history from Oxford. He topped the Bar exams, and was called to the Bar in 1959, joining chambers headed by Leslie (later Lord) Scarman. He took silk at just 38. His style of advocacy has been described as quiet and persuasive, with cool understatement, such that when he stressed a particular word or phrase, he achieved great impact.

Tom Bingham was born in London in 1933, and after national service graduated with first class honours in modern history from Oxford. He topped the Bar exams, and was called to the Bar in 1959, joining chambers headed by Leslie (later Lord) Scarman. He took silk at just 38. His style of advocacy has been described as quiet and persuasive, with cool understatement, such that when he stressed a particular word or phrase, he achieved great impact.

He became a judge of the Queens Bench Division in 1980 at the age of 46. When asked why he had become a judge he said:

“I found I liked my clients less as time went on and they got richer. I got on very well with criminals in earlier days.”

After six years as a trial judge, serving in the Commercial Court, he was appointed to the Court of Appeal. Barristers describe appearing before him as an intellectual challenge. In a recent tribute, Alex Bailin QC wrote:

“It was immediate to everyone who came into contact with him that he was both a great mind as well as an exceptionally talented judge. Like the best judges, in addition to his formidable intellect he was an extremely good listener. He always commanded his court with absolute authority yet without overtly wielding the considerable power he was invested with. He was unfailingly courteous and patient. Many eminent advocates have remarked that he managed to control the hearing of case more by the careful use of tone of voice rather than any irascibility. There was a certain type of ‘yes’ which he uttered which most definitely meant ‘move along swiftly, please’. Perhaps the best moment for counsel in a hearing before him was, whether he was seemingly with or against you, when he might helpfully distill your inelegant points into an impossibly concise summary which could be gratefully adopted with alacrity. The worst moment was probably his uncanny ability to construct a devastating counter-example which Counsel had not thought of. And you often felt as though, even after the most complex of cases, given an hour or so he could have given an extempore judgment.”1

In 1992 Lord Bingham was appointed as Master of the Rolls. He was the first senior member of the English judiciary to advocate the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into English law, and supported reforms of the civil justice system that are associated with his successor, Lord Woolf.

In 1996 Lord Bingham was asked by the Lord Chancellor to become Lord Chief Justice: an appointment resisted in some quarters because of his lack of criminal law experience. This promotion from Master of the Rolls was unprecedented in the modern era. During his time as Master of the Rolls, he had fewer publicised controversies with the Home Secretary than his predecessor, but fought with determination for the independent judiciary. He was critical of government plans to impose mandatory minimum sentences and end automatic remission for prisoners. He responded to media portrayals of judges as excessively lenient, and argued that judges were best placed to decide which sentence fitted the circumstances of the case. Whilst wary of the media, he was prepared to speak out on controversial issues, calling for reform of cannabis laws and for the provision of safe houses for released sex offenders. He also supported the abolition of mandatory life sentences for murder, and opposed plans to dismantle legal aid.

Unlike his predecessors as Lord Chief Justice — Lords Widgery, Lane and Taylor — who devoted most of their time to presiding over criminal appeals, Lord Bingham also sat in judicial review cases and civil appeals. To acquire fresh knowledge, he occasionally sat as a trial judge in Crown Courts. His contributions to the law included development of the law of confidence to protect individuals against invasions of privacy by the media.

Unlike his predecessors as Lord Chief Justice — Lords Widgery, Lane and Taylor — who devoted most of their time to presiding over criminal appeals, Lord Bingham also sat in judicial review cases and civil appeals. To acquire fresh knowledge, he occasionally sat as a trial judge in Crown Courts. His contributions to the law included development of the law of confidence to protect individuals against invasions of privacy by the media.

The move to Senior Law Lord in 2000 was not in accordance with the practice of appointing the longest-serving member of the judicial committee of the House of Lords. His appointment coincided with the commencement of the Human Rights Act. Alex Bailin QC writes:

“Despite having had a largely commercial practice at the Bar, his legal legacy will surely be grounded in the body of human rights jurisprudence which he created from 2000 until his retirement in 2008… Although his Opinions in human rights cases were generally measured in tone, he was undeniably a passionate supporter of the Human Rights Act. In his address (when he was Lord Chief Justice) to the House of Lords during the passage of the Human Rights Bill, he famously quoted Milton’s Areopagitica in support of the proposed progressive reform: ‘Let not England forget her precedence of teaching nations how to live.’ ”

Within a year of his appointment, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York led to the enactment anti-terrorist legislation and the detention of foreign terrorist suspects indefinitely without charge in Belmarsh prison, South-East London. The British government also supported the use of evidence that had been obtained by torture in certain legal proceedings. Challenges to these laws and practices led the Law Lords into apparent conflict with the government of the day.

Lord Bingham wrote the leading judgments in 2004 and 2005 in the two cases of A and Others v Secretary of State for the Home Department, although Lord Hoffmann’s powerful concurring judgment in the first Belmarsh case attracted more media attention. Their judgments recognized the threat posed to modern liberal democracies by terrorism, whilst subjecting government responses to that threat to the rule of law.

In A v Home Secretary2 the House of Lords held that the detention without trial of foreign nationals suspected of terrorism was disproportionate and discriminatory. Lord Bingham described how the appellant’s proportionality argument was able “to draw on the long libertarian tradition of English law, dating back to chapter 39 of Magna Carta 1215, given effect in the ancient remedy of habeas corpus, declared in the Petition of Right 1628, upheld in a series of landmark decisions down the centuries and embodied in the substance and procedure of the law to our own day.”

He observed that “While any decision made by a representative democratic body must of course command respect, the degree of respect will be conditioned by the nature of the decision”, and cited La Forest J who had written in a Canadian case:

“Courts are specialists in the protection of liberty and the interpretation of legislation and are, accordingly, well placed to subject criminal justice legislation to careful scrutiny. However, courts are not specialists in the realm of policy-making, nor should they be.” 3

Reference was also made to the judgment of Jackson J in the US Supreme Court case of West Virginia State Board of Education v Barnette4, who wrote in relation to a constitutionally-entrenched Bill of Rights:

“The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts ….. We cannot, because of modest estimates of our competence in such specialties as public education, withhold the judgment that history authenticates as the function of this Court when liberty is infringed.”

The leading judgment of Lord Bingham in the first Belmarsh case explains the role of judges under a statutory bill of rights, and the scope for deference to decisions by a representative democratic body. In an earlier case, Simon Brown LJ had observed that:

“… judges nowadays have no alternative but to apply the Human Rights Act 1998. Constitutional dangers exist no less in too little judicial activism as in too much. There are limits to the legitimacy of executive or legislative decision-making, just as there are to decision-making by the courts.”5

In A v Home Secretary Lord Bingham concluded that the appellants were entitled to invite the courts to review, on proportionality grounds, the relevant order and the compatibility with the Convention of the relevant Act, and that the courts were not effectively precluded by any doctrine of deference from scrutinising these issues. He did not accept a distinction drawn in a submission by the Attorney-General between democratic institutions and the courts. Lord Bingham stated:

It is of course true that the judges in this country are not elected and are not answerable to Parliament. It is also of course true, as pointed out … above, that Parliament, the executive and the courts have different functions. But the function of independent judges charged to interpret and apply the law is universally recognised as a cardinal feature of the modern democratic state, a cornerstone of the rule of law itself. The Attorney General is fully entitled to insist on the proper limits of judicial authority, but he is wrong to stigmatise judicial decision-making as in some way undemocratic.

Lord Steyn later characterised that as a “magisterial rebuke”.

In the second Belmarsh case6 the House of Lords rejected the admissibility of evidence tainted by torture. Lord Bingham explained the protections afforded by the British common law in addition to those provided by the European Convention on Human Rights. His masterful account of the common law concerning the admission of evidence obtained by torture starts with the simple sentence: “ It is, I think, clear that from its very earliest days the common law of England set its face firmly against the use of torture.” He concluded that the “principles of the common law … compel the exclusion of third-party torture evidence as unreliable, unfair, offensive to ordinary standards of humanity and decency and incompatible with the principles that should animate a tribunal seeking to administer justice”. He dissented on the issue of the burden of proof. The majority ruled that the person wishing to challenge the admissibility of the evidence had to prove that it had been obtained by torture. Lord Bingham remarked:

In the second Belmarsh case6 the House of Lords rejected the admissibility of evidence tainted by torture. Lord Bingham explained the protections afforded by the British common law in addition to those provided by the European Convention on Human Rights. His masterful account of the common law concerning the admission of evidence obtained by torture starts with the simple sentence: “ It is, I think, clear that from its very earliest days the common law of England set its face firmly against the use of torture.” He concluded that the “principles of the common law … compel the exclusion of third-party torture evidence as unreliable, unfair, offensive to ordinary standards of humanity and decency and incompatible with the principles that should animate a tribunal seeking to administer justice”. He dissented on the issue of the burden of proof. The majority ruled that the person wishing to challenge the admissibility of the evidence had to prove that it had been obtained by torture. Lord Bingham remarked:

“My noble and learned friend Lord Hope proposes…the following test: is it established, by means of such diligent enquiries into the sources that it is practicable to carry out and on a balance of probabilities, that the information relied on by the Secretary of State was obtained under torture? This is a test which, in the real world, can never be satisfied. The foreign torturer does not boast of his trade. The security services, as the Secretary of State has made clear, do not wish to imperil their relations with regimes where torture is practised. The special advocates have no means or resources to investigate. The detainee is in the dark. It is inconsistent with the most rudimentary notions of fairness to blindfold a man and then impose a standard which only the sighted could hope to meet.”7

Lord Bingham did not regard the European Convention on Human Rights as a panacea. He invoked Hamlet in a traffic case:

“Judicial recognition and assertion of the human rights defined in the Convention is not a substitute for the processes of democratic government but a complement to them. While a national court does not accord the margin of appreciation recognised by the European Court as a supra-national court, it will give weight to the decisions of a representative legislature and a democratic government within the discretionary area of judgment accorded to those bodies…. The Convention is concerned with rights and freedoms which are of real importance in a modern democracy governed by the rule of law. It does not, as is sometimes mistakenly thought, offer relief from ‘The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to’”.8

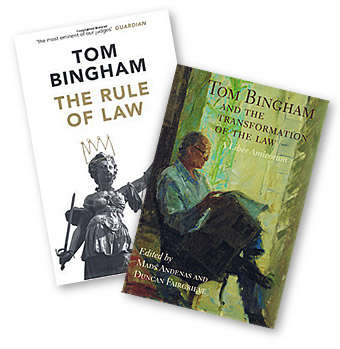

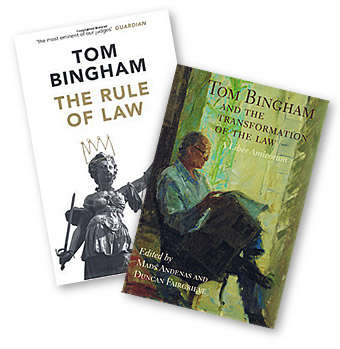

In 2008 he retired, having done much to lay the foundation for the establishment of the Supreme Court. Retirement freed him to express his opinion on the legality of the Iraq war, which he described in a lecture in November 2008 as a “serious violation of international law”. His major work The Rule of Law was published in 2010. A non-smoker throughout his life, he died of lung cancer on 11 September 2010.

In 2008 he retired, having done much to lay the foundation for the establishment of the Supreme Court. Retirement freed him to express his opinion on the legality of the Iraq war, which he described in a lecture in November 2008 as a “serious violation of international law”. His major work The Rule of Law was published in 2010. A non-smoker throughout his life, he died of lung cancer on 11 September 2010.

The Associate Editor of The Guardian, Martin Kettle, reports that Lord Bigham was amused when people assumed that Lord Bingham of Cornhill referred to the City of London rather than the tiny mid-Wales hamlet where he spent as much time as he could. No other senior judge in modern times has been made a Knight of the Garter. Lord Bingham hung the framed citation outside the bathroom door of the Welsh home in which he died.

The Director of Liberty, Shami Chakrabarti, wrote:

“As long as people anywhere fight torture and slavery; treasure free speech, fair trials, personal privacy and liberty itself — Lord Bingham will be remembered.”

Justice Peter Applegarth

Other Tributes:

Louis Blom-Cooper QC wrote in The Guardian:

“It is no exaggeration to say that Tom Bingham was the greatest judge of our time — arguably, the most significant judicial figure among the long line of notables in the history of the Anglo-Saxon legal systems. It is not just that his judicial output during an outstanding first decade of the 21st century (and the crucial last decade of the judicial House of Lords) will undoubtedly prove to be of lasting value. Over two decades — uniquely in succession as master of the rolls, lord chief justice and senior law lord — he fashioned a modern jurisprudence and displayed a juristic talent both in and out of the courtroom. He was par excellence a jurist, displaying a philosophical basis to his judgments and extra-judicial writings. His book The Rule of Law was a hugely important exposition of a phrase much overused in legal language, but little understood beyond its professional and constitutional rhetoric.

As a judge, Tom exhibited modestly an outstanding intellect, always courteously quick-witted in courtroom dialogue, as well as sure-footed in judgment, elegantly expressed, often tinged with apt historical analysis and rooted in irrefutable ratiocination. Everything he did and said was magisterial. He had all the judicial qualities and judicial mien, wholly in accordance with the highest standards of judicial service and attuned to the social and political demands made upon judges and lawyers in a civilised democracy.

Henry Porter wrote in the same publication:

He was among the first big names to agree to speak at the Convention on Modern Liberty in 2009, where he said: “The possession of great powers by the state is not a reason for using them — rather (it) should prompt a principled determination to ensure that the permissible exercise of such powers is strictly defined, regulated and monitored so as to guarantee that any intrusion into liberty and privacy of the individual is fully justified by an obviously superior community interest.” He was concerned that with the “war on terror”, government ministers were in danger of losing a basic respect for the idea that liberty is Britain’s “direct end and foundation”; and this fear inspired his important study, The Rule of Law. Tom was a great man whose humanity was as much evident in his good manners and treatment of his opponents as it is in the huge body of important judgments. But this respectfulness never inhibited a wonderfully elegant mind, and few of those who saw him argue about a written constitution with a famous television historian over dinner at Hay will forget him leaning back in his chair and engaging that terrifying mental agility. It was like watching an expert knife thrower. He will be greatly missed, for he held the line on the most important principles of law at a critical moment in our history.

Footnotes

-

- [2005] 2 AC 68; http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/2004/56.html

- RJR- MacDonald Inc v Attorney General of Canada [1995] 3 SCR 199, para 68

- 319 US 624 (1943), para 3

- International Transport Roth GmbH v Secretary of State for the Home Department

- A v Secretary of State for the Home Department (No 2) [2006] 2 AC 221; http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/2005/71.html

- Ibid, at [59] (emphasis added)

- Brown v Stott [2001] 2 WLR 817, 835; http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKPC/2000/D3.html

Tom Bingham was born in London in 1933, and after national service graduated with first class honours in modern history from Oxford. He topped the Bar exams, and was called to the Bar in 1959, joining chambers headed by Leslie (later Lord) Scarman. He took silk at just 38. His style of advocacy has been described as quiet and persuasive, with cool understatement, such that when he stressed a particular word or phrase, he achieved great impact.

Tom Bingham was born in London in 1933, and after national service graduated with first class honours in modern history from Oxford. He topped the Bar exams, and was called to the Bar in 1959, joining chambers headed by Leslie (later Lord) Scarman. He took silk at just 38. His style of advocacy has been described as quiet and persuasive, with cool understatement, such that when he stressed a particular word or phrase, he achieved great impact. Unlike his predecessors as Lord Chief Justice — Lords Widgery, Lane and Taylor — who devoted most of their time to presiding over criminal appeals, Lord Bingham also sat in judicial review cases and civil appeals. To acquire fresh knowledge, he occasionally sat as a trial judge in Crown Courts. His contributions to the law included development of the law of confidence to protect individuals against invasions of privacy by the media.

Unlike his predecessors as Lord Chief Justice — Lords Widgery, Lane and Taylor — who devoted most of their time to presiding over criminal appeals, Lord Bingham also sat in judicial review cases and civil appeals. To acquire fresh knowledge, he occasionally sat as a trial judge in Crown Courts. His contributions to the law included development of the law of confidence to protect individuals against invasions of privacy by the media. In the second Belmarsh case6 the House of Lords rejected the admissibility of evidence tainted by torture. Lord Bingham explained the protections afforded by the British common law in addition to those provided by the European Convention on Human Rights. His masterful account of the common law concerning the admission of evidence obtained by torture starts with the simple sentence: “ It is, I think, clear that from its very earliest days the common law of England set its face firmly against the use of torture.” He concluded that the “principles of the common law … compel the exclusion of third-party torture evidence as unreliable, unfair, offensive to ordinary standards of humanity and decency and incompatible with the principles that should animate a tribunal seeking to administer justice”. He dissented on the issue of the burden of proof. The majority ruled that the person wishing to challenge the admissibility of the evidence had to prove that it had been obtained by torture. Lord Bingham remarked:

In the second Belmarsh case6 the House of Lords rejected the admissibility of evidence tainted by torture. Lord Bingham explained the protections afforded by the British common law in addition to those provided by the European Convention on Human Rights. His masterful account of the common law concerning the admission of evidence obtained by torture starts with the simple sentence: “ It is, I think, clear that from its very earliest days the common law of England set its face firmly against the use of torture.” He concluded that the “principles of the common law … compel the exclusion of third-party torture evidence as unreliable, unfair, offensive to ordinary standards of humanity and decency and incompatible with the principles that should animate a tribunal seeking to administer justice”. He dissented on the issue of the burden of proof. The majority ruled that the person wishing to challenge the admissibility of the evidence had to prove that it had been obtained by torture. Lord Bingham remarked: In 2008 he retired, having done much to lay the foundation for the establishment of the Supreme Court. Retirement freed him to express his opinion on the legality of the Iraq war, which he described in a lecture in November 2008 as a “serious violation of international law”. His major work The Rule of Law was published in 2010. A non-smoker throughout his life, he died of lung cancer on 11 September 2010.

In 2008 he retired, having done much to lay the foundation for the establishment of the Supreme Court. Retirement freed him to express his opinion on the legality of the Iraq war, which he described in a lecture in November 2008 as a “serious violation of international law”. His major work The Rule of Law was published in 2010. A non-smoker throughout his life, he died of lung cancer on 11 September 2010.