FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 75 Articles, Issue 75: June 2016

by Peter Roney QC

Lord Neuberger President of the UK Supreme Court

In December just past Lord Neuberger, the UK’s most senior judge, held an audience in the palm of his hand at London’s Kingston Law School’s 50th anniversary lecture when he shared some gems of advice based on his own diverse time in the law. They cast an interesting light on some topics that would interest barristers in practice in Queensland.

“Sometimes I think that the only piece of legislation which is totally reliable is the law of unintended consequences”.

Born on 10 January 1948, Lord Neuberger was educated at Westminster School, later studied Chemistry at Christ Church, Oxford. After graduating he worked at the merchant bank, N M Rothschild & Sons from 1970-1973. He is the second President of the Supreme Court since it was opened in October 2009 to replace the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. He previously held the post of Master of the Rolls from 1 October 2009.

After ambitiously undertaking to address eight varied topics within his one hour slot, Lord Neuberger took the audience on a whistle stop canter through his career providing responses to questions and distributing nuggets of advice along the way. Topics he touched on included; the separation of powers and rule of law, EU law, the closure of courts, privacy in an online era, methods used by legal practitioners as compared to those used by scientists and the Magna Carta.

“I stand before you as someone near the end of his legal career and I see before me many people at the start of theirs,” he said, “I thought that I could perhaps pass on to you a few lessons drawn from my educational and professional experiences.”

He had come very late to the law, Lord Neuberger said, having originally studied science at university. “It took four years on a chemistry degree before it hit home that I was not a scientist and I thought I’d try my hand at banking,” he added. “If I was a poor scientist, I was a worse banker — I think if I had stayed in banking the 2008 financial crisis would have come thirty years earlier than it did.”

Lord Neuberger had not opened a law book until he was 25 and had spent a year being, in his words, ‘a bad banker during the day and studying for his bar exams at night’. In the early days his third and final choice of career had not looked promising either, though. “I had three pupillages in successive sets of chambers, each of which resulted in someone other than me being taken on,” he admitted.

Having failed to get in to one of these three (in his words) ‘upmarket and glamorous’ commercial chambers, Lord Neuberger had to settle for a pupillage at a set of chambers which specialised in landlord and tenancy cases. “Admittedly, when I started my fourth pupillage, I felt a sense of failure even though it was there that I finally got my break when they took me on,” he said. “In the event, it was the right move because, as they were small and specialised, I was given a lot of responsibility early on — taking on cases on my own and fighting them in court.”

This was the first lesson he wanted to pass on, Lord Neuberger said. “I learnt that what appears at the time to be a pointless experience often turns out to be very valuable,” he added. When he was in the Court of Appeal, Lord Neuberger initially tried to turn down an offer to be the judge responsible for information technology. “In the end, though, not only did this role enable me to become almost competent at IT, it also helped me achieve my subsequent promotions as it meant I had administrative judicial experience which my colleagues didn’t possess,” he said.

Lord Neuberger said people often underestimated the role of chance in helping them to progress in the workplace. “Luck plays a very large part in everyone’s career even though successful people won’t admit this because they prefer to think that their achievements are all down to their own merit,” he explained. “Conversely, those who have been unsuccessful don’t like to say it’s as a result of bad luck as that smacks of sour grapes. It is true, though — the fact that property law took off at just the right time for my career, for example, was only down to sheer good fortune.”

It seemed to him that you could plan all you like, Lord Neuberger said, but this would almost always result in something wholly unexpected. “Sometimes I think that the only piece of legislation which is totally reliable is the law of unintended consequences,” he suggested. In addition, determination and hard work really did tend to pay off. “I stuck to law even when things did not go well at the start,” he said. “If you do not follow your dreams when you are young, you may regret it when you’re older and it’s too late.”

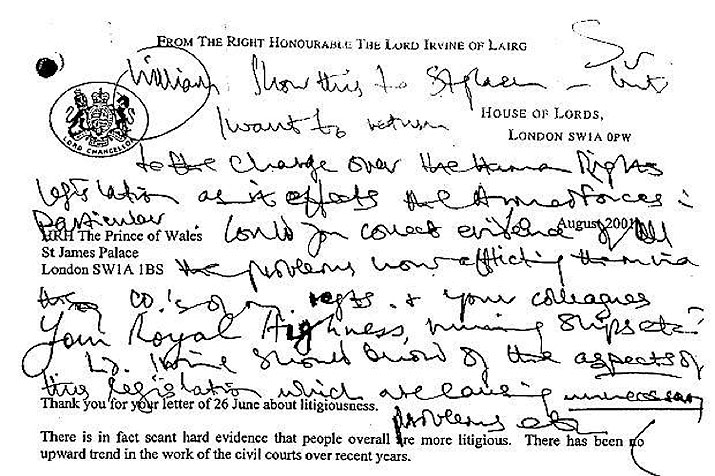

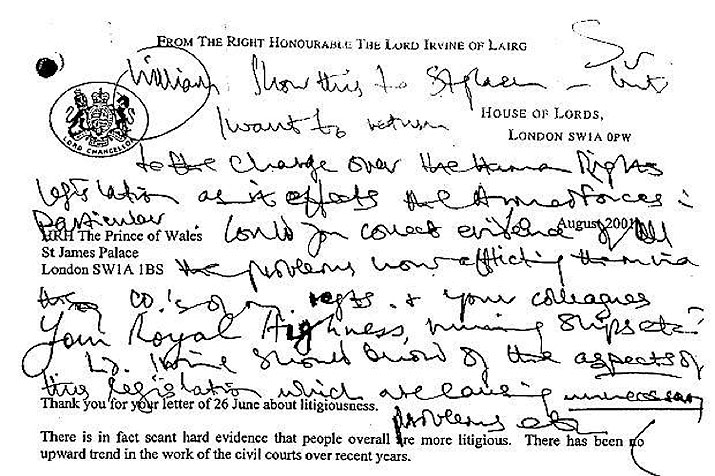

When asked what his most controversial legal decision had been, to date, Lord Neuberger revealed he had been one of the three judges who had ruled against the government decision not to publish the Prince of Wales’s ‘black spider’ letters under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act. In those letters Prince Charles wrote to Ministers about his various views on hill farms, bovine TB, military helicopters, herbal medicine, the preservation of Smithfield market, Antarctic huts and the fate of the albatross. All were written or annotated in his distinctive spidery hand (see above).All received a polite ministerial brushoff. The government spent a quarter of million pounds to avert the public’s eyes to these letters.

“These memos written by Prince Charles to ministers and politicians over a number of years were considered controversial because the monarchy is, by tradition, meant to be politically neutral,” he explained. “In the end, though, the irony was that the letters didn’t include anything very interesting and were not even especially negative towards the Prince.”