Introduction

Introduction

John F Kennedy once said:“Change is the law of life. Those who look only to the past or present are certain to miss the future” but Einstein was quoted as saying: “The problems that exist today cannot be solved by the same thinking that created them”

Anyone who tries to predict the way things will be in the future either needs a crystal ball or the skills of a prophet or a mystic, but I doubt if any of us fall into any of those catagories. In the past, at least, at best, I’d say we have been more groundhogs. Groundhogs, or land beavers, live in burrows and hibernate between October and February or March.You all know the story………Long ago, the people of Punxsutawney in Central Pennsylvania noticed their local Groundhogs emerge from hibernation in early February, most usually on February 2nd. They also noticed that if, when the Groundhog emerges for the burrow, its body does not cast a shadow on the ground, then, good news, Spring time is just around the corner. But if there is a shadow, this is bad news — Spring is still several months away, at least. So, as lawyers….are we like groundhogs? Before you rush to look it up, let me quickly assure you that, by nature, these are aggressive creatures. Their instinct is to attack and kill, not to negotiate.

Anyone who tries to predict the way things will be in the future either needs a crystal ball or the skills of a prophet or a mystic, but I doubt if any of us fall into any of those catagories. In the past, at least, at best, I’d say we have been more groundhogs. Groundhogs, or land beavers, live in burrows and hibernate between October and February or March.You all know the story………Long ago, the people of Punxsutawney in Central Pennsylvania noticed their local Groundhogs emerge from hibernation in early February, most usually on February 2nd. They also noticed that if, when the Groundhog emerges for the burrow, its body does not cast a shadow on the ground, then, good news, Spring time is just around the corner. But if there is a shadow, this is bad news — Spring is still several months away, at least. So, as lawyers….are we like groundhogs? Before you rush to look it up, let me quickly assure you that, by nature, these are aggressive creatures. Their instinct is to attack and kill, not to negotiate.

If we are to be negotiators, however, the only thing we should have in common with groundhogs is to have a body mass capable of casting a shadow — or not, as the case may be.

The effect of the adversarial environment

David Richbell is a well known mediator based in the UK. He’s been practising since 1992 and wrote and compiled the CEDR Mediator Handbook. A former Director of Training at CEDR and an accredited mediator with SPCP, he’s one of the most experienced commercial mediators (and trainers) in Europe. The curious thing is that he is not a lawyer. He has a view that because lawyers live in an adversarial environment this is not appropriate for mediation, or for the mediator. In his view, mediation is (or is meant to be) an opportunity for leaving the legal arguments outside, an opportunity for the parties to co-operate in finding the best deal for both or all of them, a place where every party is able to tell their story and listen to the other stories being told, a place where parties needs are more important than their claims, where legal rights, whilst setting the background for the discussions, become secondary to the parties wishes.

David Richbell is a well known mediator based in the UK. He’s been practising since 1992 and wrote and compiled the CEDR Mediator Handbook. A former Director of Training at CEDR and an accredited mediator with SPCP, he’s one of the most experienced commercial mediators (and trainers) in Europe. The curious thing is that he is not a lawyer. He has a view that because lawyers live in an adversarial environment this is not appropriate for mediation, or for the mediator. In his view, mediation is (or is meant to be) an opportunity for leaving the legal arguments outside, an opportunity for the parties to co-operate in finding the best deal for both or all of them, a place where every party is able to tell their story and listen to the other stories being told, a place where parties needs are more important than their claims, where legal rights, whilst setting the background for the discussions, become secondary to the parties wishes.

The questions he asks are—

- Why would a lawyer mediator be most suited to such a situation?

- What use has legal knowledge when each party almost always has their own legal representative present to give advice?

- What use has legal knowledge when deals in mediation are always commercial?

- What use has a track record of ‘winning’ when the solution is with the parties and not the Mediator?

and he answers by saying –

- The Mediator is there to enable the parties in a dispute to achieve the best deal possible.

- It is the parties’ dispute and the parties’ solution. The Mediator is there to orchestrate the event, create the right atmosphere, encourage the parties to talk openly, help them to understand each other’s needs and encourage them even when a deal seems to be impossible.

- OK, some lawyers have all those qualities, but not because they are lawyers. Rather because they have retained their ‘human’ characteristics and are able to achieve the parties trust in a very short period of time. They have what is now called Emotional Intelligence although the less enlightened still call it ‘touchy-feely’, and do so with a rather derisory tone.

Joe Markowitz,1 a constant blogger, thinks that —

- Judge mediators may be the best if the parties need an authority figure to tell them what to do;

- Non-lawyers may be best at dealing with psychological and other issues that may be preventing resolution; and

- Lawyers may be best at relating to the parties’ concerns about litigation, and arguing each side’s case to the other side. But whatever the background of the mediator, they generally need to learn additional skills to be the best all-around mediator they can be.

Richbell often makes a point about lawyer mediators as to their tendency to be evaluative by expressing an opinion on the legal merits of the case and on the likely outcome if the case progresses or, as some would say, regresses to a court hearing. This is quite a different thing from vigorous reality testing or even assertive challenging or perhaps pitching possible settlement figures.

To test an opposition’s legal representative to show how bad their case might be is the responsibility of the other, or another, party’s legal representation. It should not really be a challenge for lawyer mediators to be neutral, to be seen to be independent, even handed and unbiased.2

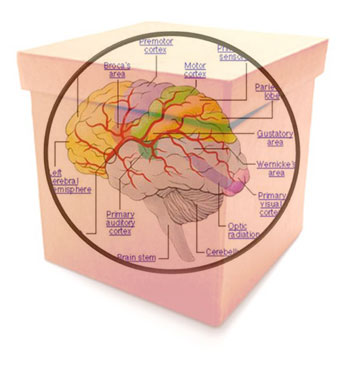

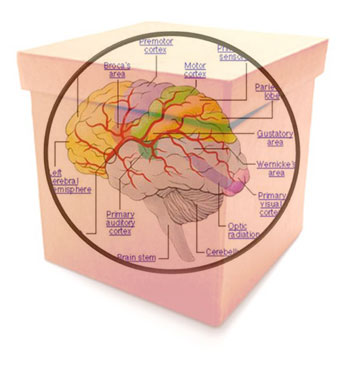

The reality is that as practicing lawyers, or trained lawyers, we are trained to analyse traditional legal rights and remedies. Such training develops a skill in logical thinking — a framework if you like within which we (as lawyers) operate — a so called “intellectual box”.3

While it is easy to fall back on this way of thinking, as mediators (those of us who are lawyers) have to think more laterally in a way which is creative, non-linear, nontraditional and intuitive but this is easier said than done.

As lawyers, we are surrounded by a web of procedural and substantive rules whether it be legislation, regulation, rules of court or practice directions. Mediation is structured; but, it is flexible. From the very basis training courses in mediation we become aware of well established rules of facilitation but it is extremely fluid in the manner in which those rules can be applied.

The need to change perspectives — mental blocks.

According to a copyright blogger, Brian Clar,4 the process boils down to changing your perspective and seeing things differently than you might currently do. For a lawyer this can be a challenge. Clarke thinks that “thinking outside the box” is the wrong way to look at it. Just like Neo needed to understand that “there is no spoon” in the film the Matrix, you need to realise “there is no box” to step out of. He puts up a number of common ways that our natural creative abilities can be suppressed. One is “trying to find the ‘right’ answer”. The point is that there is often more than one “correct” answer and a second one you might come up with might be better than the first.

According to a copyright blogger, Brian Clar,4 the process boils down to changing your perspective and seeing things differently than you might currently do. For a lawyer this can be a challenge. Clarke thinks that “thinking outside the box” is the wrong way to look at it. Just like Neo needed to understand that “there is no spoon” in the film the Matrix, you need to realise “there is no box” to step out of. He puts up a number of common ways that our natural creative abilities can be suppressed. One is “trying to find the ‘right’ answer”. The point is that there is often more than one “correct” answer and a second one you might come up with might be better than the first.

Another is “logical thinking”. I have already referred to the fact that mediation is often not logical as may be regarded in the legal sphere. Wanting a piece of flesh from somebody has no bearing logic, but it is certainly real. One way to avoid the logic of the issue is to think of the most insane solutions and work backwards. When forced to look at the absurd, the rest may become more logical.

Another mental block is “following rules”. In Clark’s view, “one way to view creative thinking is to look at it as a destructive force”. You can tear away arbitrary rules that others have set for you. Asking “why” is sometimes a powerful tool for getting out the ordinary and understanding what is actually behind the position being taken. This can be a trap. You might get stung because you’re peaking in behind the thorny problem. On the other hand, when you ask the other side ‘why’ it may take several offers at trying to unveil the reasons behind the problem.

A similar mental block is “being practical”. Clarke’s view is that injecting practicality is the worst thing to do in a creative session. In thinking creatively, one of the problems that we as lawyers have is that we don’t really want to spend time thinking of something that has no feasibility. The reality, however, is that if we think of how to make an impractical solution feasible, we might come up with a different solution that is feasible.

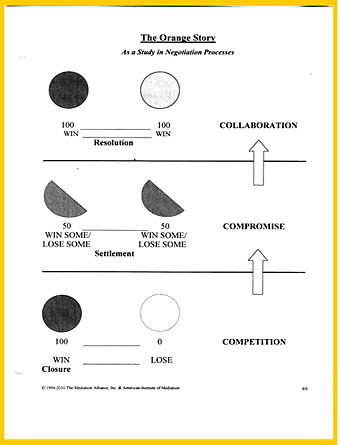

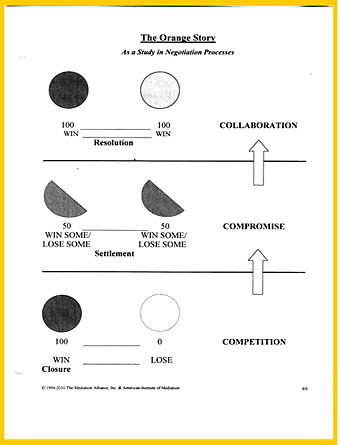

This reminds me of the orange story that I learnt from Lee Jay Berman at the American Institute of Mediation in Los Angeles.5 Most trained mediators have heard the same story or a variation of it.

Once upon a time there was a mother who had two children. One day the kids came to her fighting. There was one orange left in the house and they both wanted it. What is a parent to do? Some parents say they would take the orange away and send the kids to their rooms. Most parents would say that they would cut the orange into half giving each an equal share. Parents with more experience anticipating further argument over which half the child wants would improvise. By allowing one child to carefully cut the orange in half and then letting the other child choice the half he or she wants a parent can give an incentive to the child who cuts the orange to be as fair as possible since he or she suffers the loss if the halves are not equal. Seems fair. Fortunately this mother is a mediator. She takes the orange from the crying children and asks them why they want it. One child says to make orange juice. The other is baking muffins and wants to shave the peel into the recipe. So, with the help of their mother, the children compromise. By allowing one to make all the juice he or she wants giving the left over peel to the other only once every drop of juice has been squeezed out of it the other gets the entire peel intact. Therefore, both children are satisfied. Had these children hired legal counsel and fought this out in a court of law the only possible outcome is for one to end up with the whole orange or to split it as the judge see fits. In mediation, however, there is the possibility of discussing what each of the disputants want, and why.

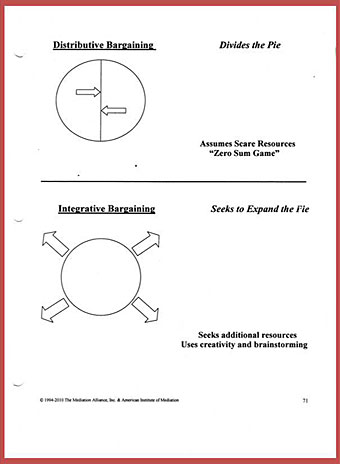

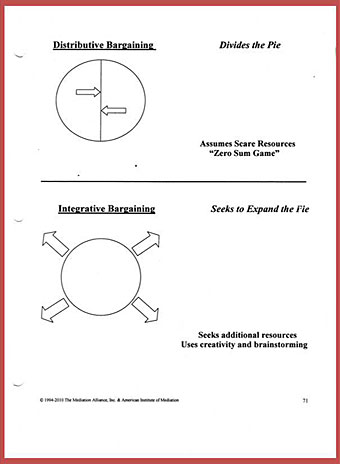

The distributive negotiating style tends to place the primary focus on positions rather than interests.

It is often characterised by adversarial approaches and competitive behaviours. When adopting this style, we have a “win/lose” perception of the negotiation’s outcome where one party “beats” the other party and the outcome of the negotiation becomes more important than the relationship. Often in a distributive style negotiation we take positions and commonly put issues of price over interests. We tend not to focus on the other side’s problems, thus creating a distinction between the parties: it is “us” versus “them”. The main focus tends to be on our own point of view and achieving victory over the other party. Immediate solutions are favoured over long term objectives, jeopardising the quality of the relationship between the parties. As the term suggests, this style of negotiating involves the distribution of outcomes. This non-lateral approach means that each party simply ends up with a portion of the asset rather than pursing the opportunity of creating new value (viz more for me means less for you).

The distributive negotiating style tends to place the primary focus on positions rather than interests.

It is often characterised by adversarial approaches and competitive behaviours. When adopting this style, we have a “win/lose” perception of the negotiation’s outcome where one party “beats” the other party and the outcome of the negotiation becomes more important than the relationship. Often in a distributive style negotiation we take positions and commonly put issues of price over interests. We tend not to focus on the other side’s problems, thus creating a distinction between the parties: it is “us” versus “them”. The main focus tends to be on our own point of view and achieving victory over the other party. Immediate solutions are favoured over long term objectives, jeopardising the quality of the relationship between the parties. As the term suggests, this style of negotiating involves the distribution of outcomes. This non-lateral approach means that each party simply ends up with a portion of the asset rather than pursing the opportunity of creating new value (viz more for me means less for you).

Integrative negotiation is also known as joint problem solving where “instead of attacking each other, you jointly attack the problem”. The parties make a commitment to work together, have two way communication and concentrate on the objectives. Thus a creative process is introduced where flexibility is encouraged and multiple alternative solutions are put on the table. This type of problem solving requires lateral thinking and creativity in order to achieve mutual gain. The result of integrative negotiation is often the creation of value and an end decision that cannot be mutually improved upon (in other words a true “win/win” outcome).

The last of many of Brian Clark’s mental block’s I will mention here is that “play is not work”. Maybe you have to have some fun in mediation upon the basis that it can’t all be work. By changing dynamics of the room or the environment or the mood you can spur creative solutions.

Just as individual jazz musicians are able to take a cue from each other for a change of key or perform a solo (intuitively), without so much as a nod or a wink from other players in the band, a mediator ought to be able to be dynamic, interactive and multidirectional and multidimensional according to his or her own sound judgment. I was shown how this is so in a real time demonstration at Pepperdine’s Strauss Institute in a summer course of Improvisational Mediation run by Jeff Krivis and Brian Brieter.6

One of the cornerstones of improvisation is the concept of “Yes, and…”

As two performers develop a scene together, each makes offers; an offer being anything they say or do that helps define the elements, reality or story of the scene they are creating. It is the responsibility of the other actor to accept the offers that their fellow performers make; in other words, to assume them to be true and act accordingly, to figuratively (and often literally) say “yes” to their scene partners.

The idea is that accepting an offer is followed by adding a new offer that builds on the earlier one; this process is known to improvisers as “Yes, and…” Every new piece of information added helps the actors refine and develop the action of the scene together. To not do so is known as blocking, negation, or denial.7

Here is a simple, but extreme, example of blocking:

Performer #1 : Hello, Mum. You don’t look well. Are you all right?

Performer #2 : I’m not your mother. I’ve never met you. And, I’ve never felt better!

In this example, the second actor negated everything the first actor offered. Let’s see what might have happened if the second actor used the concept of “Yes, and…:”

Performer #1: Hello, Mum. You don’t look well. Are you all right?

Performer #2: No, sweetheart. I’m worried about your father. He’s been working way too hard lately.

In this case the second actor says “yes” to the first by implicitly agreeing that she is her mother and that she is, in fact, not well. She then adds the information about the father working too hard. That’s the “and” part.

According to Krivis and Brieter, trial lawyers who participate in their improv classes have found the “Yes, and…” concept particularly helpful. You might ask: What on earth does improvisational comedy have to do with being a successful litigator or mediator? They say that the art and technique of improvisation involves the same tools that serve people well in any professional endeavor. When you think about it, life itself is an improvisation. Every situation is new, and therefore benefits from a fresh perspective and a creative mind. Not only that, but aren’t lawyers, in particular, essentially performers and storytellers? What lawyer could not benefit from developing these skills?”

“It improves communication and creative problem-solving skills, encourages thinking outside the box, helps to overcome fear and stumbling blocks, builds dynamic presentation and storytelling skills, increases authenticity and spontaneity, nurtures innovation, reduces negativity, and increases cooperation. Not bad, for a seemingly silly endeavor.”8

According to a survey by Professor Stephen Goldberg9 from Northwestern University, some veteran mediators believe that establishing rapport is more important than employing specific techniques and tactics. Being able to establish rapport with parties and their legal representatives is a means by which a mediator can think creatively. This doesn’t mean necessarily being able to paint “Blue Poles. It simply means thinking out of the box to work towards a resolution.

A challenge not to judge a book by its cover.

Remember the old adage, “never judge a book by its cover”? Another great challenge lawyers who mediate have is not to judge a book by its cover. Some mediators may read lengthy documentation prior to a mediation and form the conclusion that the matter will never settle. The answer is persistence with an open mind, my friends. Lee Jay Berman10 once said:

Remember the old adage, “never judge a book by its cover”? Another great challenge lawyers who mediate have is not to judge a book by its cover. Some mediators may read lengthy documentation prior to a mediation and form the conclusion that the matter will never settle. The answer is persistence with an open mind, my friends. Lee Jay Berman10 once said:

“When most people are in a dispute, the first thing they do is stop listening, or only listen with a view toward formulating arguments to prove their point. While that might help win an argument (and possibly lose a friend), it won’t resolve the conflict. The only way to settle a dispute or solve a problem of any kind is to listen carefully and with an open mind to what the other person is saying. Perhaps his or her point is actually true or has a valid basis.”

Changing the mindset

At the Mediation Roundtable Conference entitled “Changing the Mindset” held in Hong Kong in

At the Mediation Roundtable Conference entitled “Changing the Mindset” held in Hong Kong in

March last year, the Secretary for Justice, Wong Yan Lung S.C. said this –

“Now, a word about changing mindset for lawyers who act as mediators….

……..

Words such as “cooperation”, “neutrality”, “non-intervention”, “interest based needs of parties” and “peaceful conflict resolution” have become qualities sought after and the buzzwords of the new dispute resolution landscape.

Some of these qualities are not inherent in the training of lawyers; and some may even be in conflict at first brush. It is important for lawyers to change some parts of our mindset when we act as mediators. No doubt before you get accredited, you would have passed all the tests on mediation ethics. What has to be worked on include, I think, the requirement of impartiality (as opposed to pushing your client’s case come what may), the ability of effective communication (as opposed to merely giving legal opinion), the innovation and creation in terms of generating options and solutions for the consideration of the disputing parties (as opposed to just rigidly following the hard legal rules).”

The question is: “Will that just become an old Chinese saying?”

Douglas Murphy S.C.

Cedric Hampson Chambers

Footnotes

- Joseph C. Markowitz has 30 years of experience as a business trial lawyer representing clients ranging from individuals and small businesses to Fortune 500 corporations. He started practicing with a boutique litigation firm in New York City, then became a partner in a large international firm in New York, then Los Angeles, then returned to practicing with a small firm and on his own.

- See David Richbell’s “So you want an evaluative lawyer mediator do you?” at http://web.me.com/david.richbell/page11/files/796959cb1dfad7f67acc83dafdabed83-12.html

- The challenges for lawyers who become mediators: Greg Relyea, Roy Cheng: April 2010.

- Founder of Copyblogger and CEO of Copyblogger Media, a serial entrepreneur, and a recovering attorney http://www.copyblogger.com/its-all-my-fault/

- Mediating & Negotiating Commercial Cases, June 2010, AIM, Los Angeles.

- Jeffrey Krivis is the author of two books: Improvisational Negotiation: A Mediator’s Stories of Conflict about Love, Money, Angerâand the Strategies that Resolved Them, and How To Make Money As A Mediator And Provide Value To Everyone (Wiley/Jossey Bass publisher). He has been a successful mediator and a pioneer in the field for eighteen years. He is on the board of visitors of Pepperdine Law School and serves as an adjunct professor of law at the Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution. www.firstmediation.com .

Brian Brieter is a civil trial lawyer with 13 years experience in the area of Catastrophic Personal Injury. He is also an improvisational actor at the ACME Theatre in Hollywood. http://web.mac.com/brianbreiter/Law_Offices_of_Brian_Breiter/Law_Offices_Of_Brian_Breiter_Practice_Areas.html

- From “Whose Trial Is It Anyway?”, Krivis and Brieter, 2009

- Ibid.

- Stephen B. Goldberg, Professor of Law Emeritus, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois.

- President, American Institute of Mediation, Los Angeles.

Introduction

Introduction  Anyone who tries to predict the way things will be in the future either needs a crystal ball or the skills of a prophet or a mystic, but I doubt if any of us fall into any of those catagories. In the past, at least, at best, I’d say we have been more groundhogs. Groundhogs, or land beavers, live in burrows and hibernate between October and February or March.You all know the story………Long ago, the people of Punxsutawney in Central Pennsylvania noticed their local Groundhogs emerge from hibernation in early February, most usually on February 2nd. They also noticed that if, when the Groundhog emerges for the burrow, its body does not cast a shadow on the ground, then, good news, Spring time is just around the corner. But if there is a shadow, this is bad news — Spring is still several months away, at least. So, as lawyers….are we like groundhogs? Before you rush to look it up, let me quickly assure you that, by nature, these are aggressive creatures. Their instinct is to attack and kill, not to negotiate.

Anyone who tries to predict the way things will be in the future either needs a crystal ball or the skills of a prophet or a mystic, but I doubt if any of us fall into any of those catagories. In the past, at least, at best, I’d say we have been more groundhogs. Groundhogs, or land beavers, live in burrows and hibernate between October and February or March.You all know the story………Long ago, the people of Punxsutawney in Central Pennsylvania noticed their local Groundhogs emerge from hibernation in early February, most usually on February 2nd. They also noticed that if, when the Groundhog emerges for the burrow, its body does not cast a shadow on the ground, then, good news, Spring time is just around the corner. But if there is a shadow, this is bad news — Spring is still several months away, at least. So, as lawyers….are we like groundhogs? Before you rush to look it up, let me quickly assure you that, by nature, these are aggressive creatures. Their instinct is to attack and kill, not to negotiate. David Richbell is a well known mediator based in the UK. He’s been practising since 1992 and wrote and compiled the CEDR Mediator Handbook. A former Director of Training at CEDR and an accredited mediator with SPCP, he’s one of the most experienced commercial mediators (and trainers) in Europe. The curious thing is that he is not a lawyer. He has a view that because lawyers live in an adversarial environment this is not appropriate for mediation, or for the mediator. In his view, mediation is (or is meant to be) an opportunity for leaving the legal arguments outside, an opportunity for the parties to co-operate in finding the best deal for both or all of them, a place where every party is able to tell their story and listen to the other stories being told, a place where parties needs are more important than their claims, where legal rights, whilst setting the background for the discussions, become secondary to the parties wishes.

David Richbell is a well known mediator based in the UK. He’s been practising since 1992 and wrote and compiled the CEDR Mediator Handbook. A former Director of Training at CEDR and an accredited mediator with SPCP, he’s one of the most experienced commercial mediators (and trainers) in Europe. The curious thing is that he is not a lawyer. He has a view that because lawyers live in an adversarial environment this is not appropriate for mediation, or for the mediator. In his view, mediation is (or is meant to be) an opportunity for leaving the legal arguments outside, an opportunity for the parties to co-operate in finding the best deal for both or all of them, a place where every party is able to tell their story and listen to the other stories being told, a place where parties needs are more important than their claims, where legal rights, whilst setting the background for the discussions, become secondary to the parties wishes. According to a copyright blogger, Brian Clar,4

According to a copyright blogger, Brian Clar,4 The distributive negotiating style tends to place the primary focus on positions rather than interests.

It is often characterised by adversarial approaches and competitive behaviours. When adopting this style, we have a “win/lose” perception of the negotiation’s outcome where one party “beats” the other party and the outcome of the negotiation becomes more important than the relationship. Often in a distributive style negotiation we take positions and commonly put issues of price over interests. We tend not to focus on the other side’s problems, thus creating a distinction between the parties: it is “us” versus “them”. The main focus tends to be on our own point of view and achieving victory over the other party. Immediate solutions are favoured over long term objectives, jeopardising the quality of the relationship between the parties. As the term suggests, this style of negotiating involves the distribution of outcomes. This non-lateral approach means that each party simply ends up with a portion of the asset rather than pursing the opportunity of creating new value (viz more for me means less for you).

The distributive negotiating style tends to place the primary focus on positions rather than interests.

It is often characterised by adversarial approaches and competitive behaviours. When adopting this style, we have a “win/lose” perception of the negotiation’s outcome where one party “beats” the other party and the outcome of the negotiation becomes more important than the relationship. Often in a distributive style negotiation we take positions and commonly put issues of price over interests. We tend not to focus on the other side’s problems, thus creating a distinction between the parties: it is “us” versus “them”. The main focus tends to be on our own point of view and achieving victory over the other party. Immediate solutions are favoured over long term objectives, jeopardising the quality of the relationship between the parties. As the term suggests, this style of negotiating involves the distribution of outcomes. This non-lateral approach means that each party simply ends up with a portion of the asset rather than pursing the opportunity of creating new value (viz more for me means less for you). Remember the old adage, “never judge a book by its cover”? Another great challenge lawyers who mediate have is not to judge a book by its cover. Some mediators may read lengthy documentation prior to a mediation and form the conclusion that the matter will never settle. The answer is persistence with an open mind, my friends. Lee Jay Berman10

Remember the old adage, “never judge a book by its cover”? Another great challenge lawyers who mediate have is not to judge a book by its cover. Some mediators may read lengthy documentation prior to a mediation and form the conclusion that the matter will never settle. The answer is persistence with an open mind, my friends. Lee Jay Berman10 At the Mediation Roundtable Conference entitled “Changing the Mindset” held in Hong Kong in

At the Mediation Roundtable Conference entitled “Changing the Mindset” held in Hong Kong in