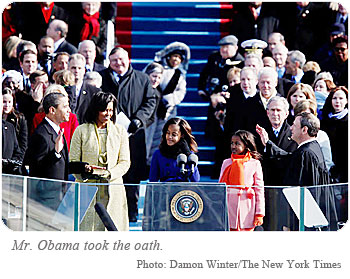

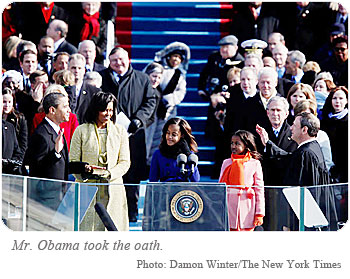

There was a false start by Mr. Obama, who started to respond before Chief Justice Roberts had completed the first phrase. Mr. Obama ended up saying the first two words â “I, Barack” â twice.

Then there was an awkward pause after Chief Justice Roberts prompted Mr. Obama with these words: “That I will execute the office of president to the United States faithfully.” The Chief Justice seemed to say “to” rather than “of,” but that was not the main problem. The main problem was that the word “faithfully” had floated upstream in the constitutional text, which reads: “That I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States.”

Then there was an awkward pause after Chief Justice Roberts prompted Mr. Obama with these words: “That I will execute the office of president to the United States faithfully.” The Chief Justice seemed to say “to” rather than “of,” but that was not the main problem. The main problem was that the word “faithfully” had floated upstream in the constitutional text, which reads: “That I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States.”

Mr. Obama seemed to realize this, pausing quizzically after saying, “that I will execute.” Chief Justice Roberts gave it another try, getting closer but still not quite right with this: “Faithfully the office of president of the United States.” He omitted the word “execute.” Mr. Obama then repeated the Chief Justice’s error of putting “faithfully” at the end and said, “The office of president of the United States faithfully.”

Following the ceremony, the bumbling administration of the oath was the talk of the town. Some commentators speculated as to whether the failure to utter the words in the precise order required by the Constitution meant that there the legitimacy of Mr Obama’s presidency could be impugned.

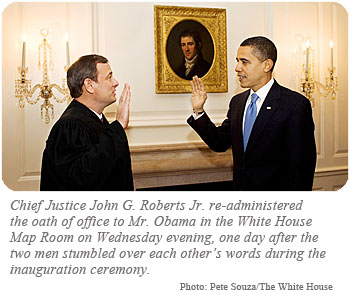

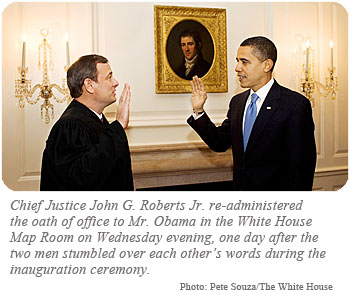

If you think that is a ridiculous proposition, well think again because Mr Obama’s advisers were so concerned that they arranged for the Oath of Office to be re-administered the next day.

In an article in the New York Times on 22 January, Jeff Zeleny reported that, at a luncheon after the first swearing-in, Chief Justice Roberts could be seen on camera telling Mr Obama that the mistake was “my fault” and so he agreed to travel to the White House for Take 2.

For what was described as a “do-over”, Mr Obama and Chief Justice Roberts convened in the White House Map Room at 7:35 pm for a brief proceeding that was not announced until it was completed successfully.

For what was described as a “do-over”, Mr Obama and Chief Justice Roberts convened in the White House Map Room at 7:35 pm for a brief proceeding that was not announced until it was completed successfully.

“Are you ready to take the oath?” Chief Justice Roberts said.

“I am,” Mr. Obama replied. “And we’re going to do it very slowly.”

While about two million people were on hand to watch the first swearing-in, a figure that does not include the hundreds of millions who watched it on television in the United States and around the world, only nine people witnessed the do-over. There were four aides, four reporters and a White House photographer present for the “do-over”.

“Congratulations again,” Mr. Roberts said after the flawless recitation. “Thank you, sir,” replied Mr. Obama.

Surprising as all this may seem, it was not the first time in the history of the US Presidency that a “do-over” has been required. When questions were raised about whether it was proper for Calvin Coolidge to have been sworn in by his father, a notary public, after the death of Warren Harding in 1923, Coolidge took the oath again from a federal judge.

All of this prompted the following article by Steven Pinker in the 22 January edition of the New York Times.

In 1969, Neil Armstrong appeared to have omitted an indefinite article as he stepped onto the moon and left earthlings puzzled over the difference between “man” and “mankind.” In 1980, Jimmy Carter, accepting his party’s nomination, paid homage to a former vice president he called Hubert Horatio Hornblower. A year later, Diana Spencer reversed the first two names of her betrothed in her wedding vows, and thus, as Prince Charles Philip supposedly later joked, actually married his father.

On Tuesday, Chief Justice John Roberts joined the Flubber Hall of Fame when he administered the presidential oath of office apparently without notes. Instead of having Barack Obama “solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States,” Chief Justice Roberts had him “solemnly swear that I will execute the office of president to the United States faithfully.” When Mr. Obama paused after “execute,” the chief justice prompted him to continue with “faithfully the office of president of the United States.” (To ensure that the president was properly sworn in, the chief justice re-administered the oath Wednesday evening.)

How could a famous stickler for grammar have bungled that 35-word passage, among the best-known words in the Constitution? Conspiracy theorists and connoisseurs of Freudian slips have surmised that it was unconscious retaliation for Senator Obama’s vote against the chief justice’s confirmation in 2005. But a simpler explanation is that the wayward adverb in the passage is blowback from Chief Justice Roberts’s habit of grammatical niggling.

Language pedants hew to an oral tradition of shibboleths that have no basis in logic or style, that have been defied by great writers for centuries, and that have been disavowed by every thoughtful usage manual. Nonetheless, they refuse to go away, perpetuated by the Gotcha! Gang and meekly obeyed by insecure writers.

Among these fetishes is the prohibition against “split verbs,” in which an adverb comes between an infinitive marker like “to,” or an auxiliary like “will,” and the main verb of the sentence. According to this superstition, Captain Kirk made a grammatical error when he declared that the five-year mission of the starship Enterprise was “to boldly go where no man has gone before”; it should have been “to go boldly.” Likewise, Dolly Parton should not have declared that “I will always love you” but “I always will love you” or “I will love you always.”

Any speaker who has not been brainwashed by the split-verb myth can sense that these corrections go against the rhythm and logic of English phrasing. The myth originated centuries ago in a thick-witted analogy to Latin, in which it is impossible to split an infinitive because it consists of a single word, like dicere, “to say.” But in English, infinitives like “to go” and future-tense forms like “will go” are two words, not one, and there is not the slightest reason to interdict adverbs from the position between them.

Though the ungrammaticality of split verbs is an urban legend, it found its way into The Texas Law Review Manual on Style, which is the arbiter of usage for many law review journals. James Lindgren, a critic of the manual, has found that many lawyers have “internalized the bogus rule so that they actually believe that a split verb should be avoided,” adding, “The Invasion of the Body Snatchers has succeeded so well that many can no longer distinguish alien speech from native speech.”

In his legal opinions, Chief Justice Roberts has altered quotations to conform to his notions of grammaticality, as when he excised the “ain’t” from Bob Dylan’s line “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose.” On Tuesday his inner copy editor overrode any instincts toward strict constructionism and unilaterally amended the Constitution by moving the adverb “faithfully” away from the verb.

President Obama, whose attention to language is obvious in his speeches and writings, smiled at the chief justice’s hypercorrection, then gamely repeated it. Let’s hope that during the next four years he will always challenge dogma and boldly lead the nation in new directions.

Photo at top of article: © Alex Wong/Getty Images

Then there was an awkward pause after Chief Justice Roberts prompted Mr. Obama with these words: “That I will execute the office of president to the United States faithfully.” The Chief Justice seemed to say “to” rather than “of,” but that was not the main problem. The main problem was that the word “faithfully” had floated upstream in the constitutional text, which reads: “That I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States.”

Then there was an awkward pause after Chief Justice Roberts prompted Mr. Obama with these words: “That I will execute the office of president to the United States faithfully.” The Chief Justice seemed to say “to” rather than “of,” but that was not the main problem. The main problem was that the word “faithfully” had floated upstream in the constitutional text, which reads: “That I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States.” For what was described as a “do-over”, Mr Obama and Chief Justice Roberts convened in the White House Map Room at 7:35 pm for a brief proceeding that was not announced until it was completed successfully.

For what was described as a “do-over”, Mr Obama and Chief Justice Roberts convened in the White House Map Room at 7:35 pm for a brief proceeding that was not announced until it was completed successfully.