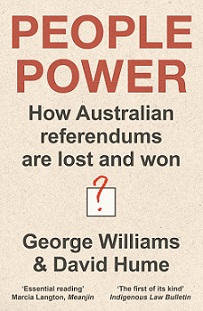

Authors: George Williams and David Hume

Publisher: NewSouth Publishing

Reviewed by Brian Morgan

I was surprised to find out how many referendums I had voted in since being added to the electors’ roll. By my count, there have been 45 since 1900 in 20 polls and I have voted in 8 of that 20.

In that period of time, quite obviously, we have gone from communications’ infancy to the digital age. Imagine, if you can, a newspaper today, writing in these terms:

“Last night’s protracted sitting thoroughly demoralised the House of Representatives. A handful of Opposition members, a little knot of Labour members, and one or two ministerialists, maintained the semblance of a deliberative assembly, whilst the other members whose physical presence was necessary for the maintenance of a quorum, bandaged their eyes as protection against the electric light, and slept away the time on the benches” (Text page 146-7).

The authors take us through a history of referendums in Australia, those that voted “yes” and those which voted “no”, with detailed explanations for the results.

One point in particular stood out because it was clear to me that it has become more frequent as time has passed. That is, “Truth is one of the first casualties in any referendum campaign … Referendums are often characterised by a heavy reliance on material that is demonstrably false”. (Text page 295).

The authors give us a deep insight into the more recent referendums but, for now, I will confine my comments to “the Voice” referendum of 2023 as it should be fresh in all of our minds.

The amount of money poured into this referendum has been assessed by the Australian Electoral Commission at more than $336,600,000. Just think what we got for this massive expenditure. That sum alone is the cost of the referendum including over $M10 to produce the yes/no pamphlet, $M12 for the NIAA and the Museum of Australian Democracy for neutral public civics education and awareness activities, $M10.5 to the Department of Health and Aged Care to increase mental health supports for First Nations people during the period of the referendum and $M5.5 to the National Indigenous Australians Agency for consultation, policy and delivery connected to holding the referendum.

The 1999 referendum by way of example, cost $M66.

We probably remember that the 1999 Referendum focussed on the proposal for Australia to become a Republic. . The investigation by the authors of the respective sides of this debate is almost amusing in hindsight. For instance, one advertisement in November 1999, said, “This Republic: Don’t risk it … If you want to vote for the President, Vote NO to the Politician’s Republic”.

On the other hand, the proponents of the “yes” vote argued that Australia’s relations with its neighbours were being impaired by its continuing ties to the monarchy.

And you may recall there was not even a consensus prior to the Referendum as to which type of republic was better. The “no“ vote took advantage of this by comments such as “the Politician’s Republic” referring to whether the President would be appointed and dismissed by the Parliament or the people.

There is an extensive appraisal of the 2023 Referendum. Let me ask you this simple question: “Can you describe in a few sentences the detail of what was proposed in last year’s referendum?” I have tried this question on a number of people whilst preparing this review. Virtually nobody gives an identical answer and most answers don’t agree with my answer. One person had been heavily involved in promoting the “yes” vote, working with a Teal member of the House of Representatives. Her understanding of “the Voice” bore little relationship to what the Prime Minister said.

Perhaps, to explain this, if, for no other reason, reading this book is particularly useful. I think it demonstrates that, even now, Governments continue to make the mistakes that they should have identified in prior referendums, mistakes such as not explaining in simple and coherent terms, what is intended. This referendum was not the first time, for instance, that the Parliament proposed to retain a role in determining the manner in which a successful referendum would be implemented.

I suspect that most of us would feel uncomfortable in suggesting to a jury that, if they found our client guilty, they may determine what punishment should be meted out without any guidance from us. Similarly, prospective voters could well be uncomfortable in giving the Parliament a power over which we, the voters, have no say in how the vote or votes given for change will be carried out.

Summary: I suppose it is obvious to readers that I remain deeply interested in the law, and the laws. Australian Constitutional Law was a favourite subject of mine as an undergraduate, nearly 60 years ago. This book has provided a great insight into the provisions of the Commonwealth legislation which control referendums, why so many have failed, suggestions by the authors as to what should change in that process and why, as well as thought provoking comments from which we leave the book with a host of questions over which to ponder.

This is a really useful insight into referendums in Australia and, if you have the slightest interest in the process, I encourage you to read and digest this first rate book.