In his second reading speech on 11 March 2003, Mr Welford, the Attorney-General, stated that the introduction of the proportionate liability (“PL) regime erected by Chapter 2, Part 2 of the Civil Liability Act 2004 (Qld) (“CLA”) was “in response to the concerns raised by professional bodies about excessive professional indemnity premiums and the potential for unlimited liability for large claims”1.

How did the CLA fare for the Solicitors for the subject claim? In answering this question I will firstly deal with the causes of action the Lender has pursued against the Solicitors, in order to determine whether the Solicitors can take the benefit of the PL regime erected by the CLA, or the regime under any other relevant statute.

Lender’s causes of action against the Solicitors

The factual analysis shows that (absent negligence by the Solicitors and others) this loan transaction would not have occurred. In particular, had the Solicitors used reasonable care and skill in the giving of their advice, the title to the security property would have been demonstrated to have been defective (in a matter critical to its valuation) and therefore the loan transaction would not have occurred. The Lenders resulting loss is calculated as follows:

Sum lent to borrower

$2,000,000

Sum recovered from security

$500,000

Value of security at time of loan

$750,000

Loss

$1,500,000

Amount of contributory negligence by plaintiff

0%

Recoverable loss

$1,500,000

To recover its loss, the Lender can sue the Solicitors in contract (for breach of the implied term in the retainer that the Solicitors would exercise that degree of care and skill which would be exercised by a reasonably competent Solicitors) and in tort for breach of a similar duty, arising by reason of the existence of the retainer.

There is no Fair Trading Act claim by the Lender (regardless of the facts), because the Lender is a corporation and therefore cannot be a consumer under the FTA (FTA s.6). Only a consumer can bring an action for damages for a contravention of the FTA misleading conduct provision, s.38: FTA, s.99 (4).

In the seminar problem, the Lender has not pleaded any Federal misleading conduct claim. It might have done so, relying on s.82 of the TPA as a basis for damages for breach of s.52 of the TPA, even though the Solicitors are not a corporation: see s.6 (3) of the TPA.

Alternatively, if the conduct by the Solicitors was conduct in relation to either “financial services” or a “financial product”, or a “financial service”, the Lender may have been able to sue the Solicitors for damages for misleading conduct under s.1041H of the Corporations Act 2001 or s.12DA of the Australian Securities & Investment Commission Act 2001.

The next issue is which of those causes of action are “solidary” claims and which “apportionable claims” under relevant State and Federal legislation, and why this is so.

Apportionable claims

The Lender’s retainer with the Solicitors arose in Queensland, and was breached in Queensland and the loss occurred in Queensland. In these unambiguous circumstances, at least as far as the Solicitors are concerned, the proper law of PL is the law of Queensland: Rogerson [2002] 203 CLR 503 at [81]. In cases involving cross- jurisdictional wrongdoing, it may be necessary to select another PL law as applying to the claim.

I take the view that both causes of action advanced by the Lender against the Solicitors are “claims “ and “apportionable claims” under the relevant legislation, the CLA. Why ?

The key provision is CLA s.28(1).

The plaintiff’s pleadings, that is to say the way that a plaintiff articulates its claim, are not determinative of whether the claim is an “apportionable claim” . The nature of the claim is not determined by the words in which it is framed2. The word “claim” refers to a claim as proved and established, not a claim as made or advanced3.

Having regard to the Dictionary definitions of the words “claim”, “duty” and “duty of care” in CLA s.28(1) it is clear that the Lenders causes of action against the Solicitors are for economic loss “in an action for damages arising from a breach of a duty of care”.

Having regard to the Dictionary definitions of the words “claim”, “duty” and “duty of care” in CLA s.28(1) it is clear that the Lenders causes of action against the Solicitors are for economic loss “in an action for damages arising from a breach of a duty of care”.

The term “duty of care” means “a duty to take reasonable care or to exercise reasonable skill (or both duties)” and applies whether that duty is in tort , or under a contract imposing a duty which is concurrent and co-extensive with a duty of care in tort. There is a slight difference in wording between CLA 28 and other State analogues. There have been no reported cases on CLA s.28, so it is difficult to see whether the Courts will find any practical distinction between a claim for damages “arising from a breach of a duty of care” and for damages “arising from a failure to take reasonable care”, the New South Wales definition. For the purposes of the current problem, the distinction would be immaterial.

If the Solicitors warranted to produce a particular result, a claim for damages arising from breach of that warranty would not be an apportionable claim under CLA 28. This is because the Solicitors would not have failed to exercise reasonable care and skill, they would have simply failed to produce what they contracted to produce.

Sometimes the dividing line between a promise to do something, and a promise to do something with reasonable care, will be a fine one, but generally in professional negligence cases, the promise is to take reasonable care or exercise reasonable skill in the task entrusted. This is such a case. Here, the Solicitors retainer to check the title to the security property can hardly be described as a retainer “to provide something”. In my view it is rather a retainer to advise, in the context of a mortgage lending risk. The same can be said, perhaps less forcefully, in relation to the retainer to calculate the maximum loan amount for insertion in the loan documents.

The warranties in building case can be a useful contrast. A contract with a builder to build a house of a particular design involves the assumption of a number of contractual duties , including supplying material of adequate quality and in accordance with the specification , and carrying out the work itself with the care and skill to be expected of a skilled tradesman. However, in the standard case of a breach ( by the use of non-specified materials , or in a way inconsistent with the design drawings ) the complaint is not that the builder failed to exercise reasonable care and skill, but rather that it failed to supply what was contracted for.

The warranties in building case can be a useful contrast. A contract with a builder to build a house of a particular design involves the assumption of a number of contractual duties , including supplying material of adequate quality and in accordance with the specification , and carrying out the work itself with the care and skill to be expected of a skilled tradesman. However, in the standard case of a breach ( by the use of non-specified materials , or in a way inconsistent with the design drawings ) the complaint is not that the builder failed to exercise reasonable care and skill, but rather that it failed to supply what was contracted for.

Accordingly, having regard to the provisions of the CLA, s.28, the Lender’s claims are subject to the PL regime of Queensland.

Under the TPA , the Lender’s claim ( if advanced) would also be an apportionable claim under TPA s.87CB , as a claim for damages made under s.82 for economic loss “caused by” conduct that was done in contravention of s.52.

Joinder : who are concurrent wrongdoers?

The Lender has taken no steps to effect joinder of any concurrent wrongdoer, in breach of CLA s.32 which provides to the effect that a claimant who makes a claim to which the PL provisions apply is to make the claim against all persons the claimant “has reasonable grounds to believe may be liable for the loss and damage”.

There is a complimentary duty on the Solicitors to inform the Lender of relevant information they have access to “about the circumstances that make them believe the other person is or may be a concurrent wrongdoer in relation to the claim”: CLA 32(2). The Solicitors duty exists regardless of the Lender’s failure to abide by its complimentary duty. If necessary, the Solicitors can apply for orders for any costs thrown away as a result of Lenders failure to join the Valuer, although it is hard to see what those would be in the standard case: CLA 32(5).

In order to ensure that they get the benefit of the PL regime, the Solicitors need to join as many concurrent wrongdoers as defendants to the claim as they can.

CLA s.30 identifies that a concurrent wrongdoer in relation to a claim is a person who is “one of two or more persons whose acts or omissions caused, independently of each other, the damage that is the subject of the claim”. The question of who is a concurrent wrongdoer is to be addressed by reference to the findings as to liability and causation made in the proceedings4.

There are three questions which determine whether a party is a concurrent wrongdoer:

(a) Did the act or omission of each person cause the loss to the plaintiff?

(b) Was the act or omission of each person a wrongful one, vis a vis the plaintiff ? [It is implicit from CLA 32(1) that a concurrent wrongdoer must not only have caused, but must be legally liable for, the loss or damage to the Lender. A party cannot be a concurrent wrongdoer unless that party is liable to the Lender under the substantive law5].

(c) Is the plaintiff’s loss in each case the same loss?

It is not necessary for defendant who seeks to minimise the extent of its own liability under PL to assert a cause of action by the plaintiff against the other concurrent wrongdoer which is itself an apportionable claim, arising from a failure to take reasonable care, or one of the other descriptors. Indeed it is likely that in many cases the joinder of concurrent wrongdoers will be in respect of claims that are not themselves apportionable claims.

Pleading and joinder by defendant

Here, the Solicitors ( even at this early stage) clearly have reasonable grounds to identify the Valuer as a concurrent wrongdoer in tort or under the TPA. The Valuer expressed an opinion which (putting aside the bribe) was without a reasonable basis, and (having regard to the bribe, which the Solicitor probably does not know about) was not an opinion actually held. Therefore, the Lender could have sued the Valuer under s.82 of the TPA, or for breach of a duty of care imposed at common law arising by reason of reasonable reliance on advice given in a business context in circumstances where the Valuer knew of the intending reliance. The Lenders loss in each case is the same loss.

The Solicitors duty to advise the claimant of the identity of concurrent wrongdoers under CLA 32(2) and (3) could be satisfied by the service of an appropriately particularized and timely defence. The Solicitors should therefore file a defence claiming, in the alternative to any denial of liability, an entitlement to PL, identifying as many concurrent wrongdoers as are arguably within that category.

The Solicitors can obtain leave to join a non-party concurrent wrongdoer in the action: CLA s.32C(1)). They should do so to ensure that there is no discretionary basis for the Court to exclude the responsibility of a non-party concurrent wrongdoer at the apportionment stage: CLA s.31(3)). For Federal claims, a defendant is not required to join others to the proceeding, rather it is merely required to lead evidence regarding the other party’s comparative responsibility for the loss.

Where a non-party concurrent wrongdoer is uninsured and insolvent, it will not contest the proceedings. It seems to me that this will (or may) result in an apportionment which tends to understate the responsibility of the actively defending concurrent wrongdoers, compared to the responsibility that might have been allocated had those non-party defendants contested the proceedings.

In order to enliven the jurisdiction to permit joinder of an alleged concurrent wrongdoer, the Solicitors need only plead a case “which is not hopeless”6.

However, the pleading requirements should not be underestimated. The Solicitors must plead the existence of a particular person said to be a concurrent wrongdoer, the occurrence of an act or omission by that particular person, and a causal connection between that occurrence and the loss that is the subject of the claim7.

They must also identify the basis for the cause of action — if it be contract, identify the contract; if it be tort identify the duty, its scope and the breach, and the damage — the aspects of causation, the alleged extent and proportion of the damages and the causal connection with the damage said to be suffered by the Lender in the substance of the proceeding8.

Court assistance

If necessary, the Solicitors can invoke interlocutory processes, prior to pleading, to allow them to identify concurrent wrongdoers and the basis for those persons’ fault as against the Lender. Under UCPR 366, the Court may make any order or direction about the conduct of a proceeding it considers appropriate, and that rule would admit of considerable flexibility. That might allow pre-pleading interrogatories in an appropriate case9.

Where the issue is pre-pleading disclosure in favour of defendants who have (or assert) an entitlement to proportionate liability, there are a number of issues which are yet to be worked out in the cases. They will include , as they do in the Norwich Pharmacal10 environment, the extent to which it will be necessary for the defendant to demonstrate the existence of a cause of action in respect of which discovery is sought to aid, the extent to which disclosure should extend to “information” discovery rather than “identity” discovery , and what range of third parties will be compellable, particularly whether it will extend to persons with no connection with the wrong, other than that he or she has some document in his or her possession or power in relation to the matter11.

While the rules are not without some complexity, it would in my view be sufficient for the Solicitors to show that the Lender arguably has a cause of action against a third party , and that pre-pleading disclosure against the person concerned is reasonably necessary to enable that case to be advanced as a basis for PL , or otherwise to enable justice to be done.

Borrower as a concurrent wrongdoer

In my view the Borrower is a concurrent wrongdoer because in giving the contractual warranty (that it had and would retain sufficient net asset backing so as to be able to repay the full amount of the loan for its duration ) the Borrower gave a contractual promise for which there was no basis, which constituted misleading conduct either under TPA s.52 or one of the other misleading conduct federal statutes, which conduct misled the Lender into making the loan12. In a “no-transaction” case, the Lenders loss in each case ( against the Solicitors, the Lender and the Valuer ) is the same loss.

Here, the Lender will not seek to advance any claim against the Borrower because the Borrower is a shell and that would be a waste of money.

Planner as a concurrent wrongdoer

To complete the picture, one needs to look at the Planner’s liability. The Planner is at least arguably a concurrent wrongdoer to the Lender because it gave written advice to the Borrower (relied on by the Lender in Queensland) that the minimum lot yield was 10 lots per hectare, when careful peers would have advised that the minimum lot yield was 5 lots per hectare. The Lender relied on the Planner’s estimate and gained comfort from that advice , without which it would not have made the loan . It was reasonable for it to do so. The Lenders claim against the borrower is in tort or perhaps a TPA claim. In a “no-transaction” case, the Lenders loss in each case is the same loss.

Principles of apportionment

Principles of apportionment

The overriding principle of apportionment is set out in CLA s.31(1)(a) that the liability of a defendant who is a concurrent wrongdoer in relation to an apportionable claim is limited to an amount reflecting that proportion of the loss or damage claimed that the Court considers just and equitable, having regard to the extent of the defendant’s responsibility for the loss and damage. The Court “may” have regard to the comparative responsibility of any concurrent wrongdoer who is not a party to the proceeding.

In the decided cases under PL, blameworthiness and causative potency are recognised as determinatives in apportioning responsibility in much the same way as they were under the contribution statutes13:

(a) Any free floating notion that “equality is equity” cannot operate, even as a starting point14.

(b) The Court should apportion liability according to considerations such as (but not limited to) which of the wrongdoers was more actively engaged in the activity causing loss and which of the wrongdoers was more able effectively to prevent the loss happening.

(c) So a wrongdoer who is, in a real and pragmatic sense, more to blame for the loss than another wrongdoer should bear more of the responsibility15. Whether conduct is devoid of causative force is relevant16.

(d) The degree of a party’s departure from its expected standards is relevant.

(e) Whether a wrongdoer has profited from the wrongdoing and retains the profit may be taken into account17.

(f) When directing contribution between the two solvent defendants, it seems unlikely that the Court will have regard to the fact that one of the responsible defendants is insolvent18.

It can be seen in the Problem that one partner in the Solicitors firm deliberately refrained from advising his other partner of the existence of the statutory easement. On my analysis, this would not give rise to a claim by the Lender (in equity) against the firm for breach of a proscriptive fiduciary obligation, because no unauthorised benefit was obtained as a result. In my view the relevant breaches of duty by the Solicitors were of a non-fiduciary obligation to take care19. In my view there was no relevant dishonesty and thus no fraud20.

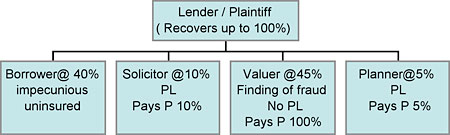

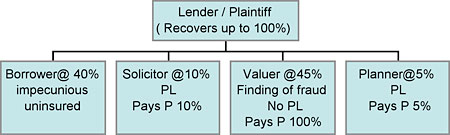

Here, neither the Solicitors or the Planner are free from culpability nor was their conduct devoid of any causative force. But there is a very significantly greater degree of culpability on the part of the Borrower and the Valuer and a significantly stronger causative force in both those parties’ conduct than in the Solicitors or the Planner.

Where a vendor bribes a Valuer to induce a Valuer to inflate the value of the security property by 25% above the justified amount, the valuation itself is fraudulent. If the Valuer is a party “against whom a finding of fraud is made”, it will be severally liable for the damages awarded against any other concurrent wrongdoer to the claim: CLA 32E. The relevant plea would be found in the Solicitors defence, to the effect that the Valuer’s liability to the Lender arises from intentionally dishonest conduct amounting to fraud. It is unclear what the boundaries of s.32E will be.

The early reported cases attributed a very great proportion of responsibility to parties who were found to have acted fraudulently : see Ginelle Finance Pty Ltd v Diakakis [2007] NSWSC 60 and Chandra v Perpetual Trustees Victoria Ltd [2007] NSWSC 694 at [111] where the split up was 90% to the fraudster and 10% to the solicitor , and Vella v Permanent Mortgages [2008] NSWSC 505 where the split was 72.5% to the fraudster and 12.5% to the solicitor.

The more recent reported cases are tending to attribute more liability to professionals who by their breach of duty failed to detect the fraud: Solak v Bank of Western Aust Ltd [2009] VSC 82 at [43] (50% to the fraudster; 35% to the advisers; and 15% to the bank) and Spiteri v Roccisano [2009] VSC 132 (40% to the fraudster; 60% to the solicitor).

In terms of blameworthiness and causative potency, the Borrowers conduct is in my view significant , and on par with the Valuer. In the result , each of the joined defendants (save for the Valuer) can say to the plaintiff that their liability to the plaintiff is proportionate.

In my view, were this case to go to trial and judgment, the apportionment would be generally as follows:

Compromise

The Valuer’s insurer is considering compromising with the plaintiff by paying it $750,000, taking into account the Valuer’s apprehended exposure personally, and its supposed exposure under the indemnity for the liability of its subsidiary, the Planner. This assumes a 50% combined liability. If the plaintiff were to accept this settlement, it might do so at its peril, because the Valuer is liable for 100% due to its fraud and the other defendants have the benefit of PL.

The plaintiff assumes the risk in settling with a defendant. A settlement at under value does not operate to increase the liability to the plaintiff of the Solicitors or the Planner. They remain able to contend at trial for the irrelevance of the compromise in respect of their liability, and that the proportionate share of the settling wrongdoer was greater than that represented by the settlement. This is because the legislation has introduced a regime in which the forensic relationship between the plaintiff and a concurrent wrongdoer defendant is seen as a series of independent claims, tied together only as a matter of convenience: Gunston v Lawley [2008] VSC 97.

Gunston was a case in which the plaintiff accepted the building surveyor’s offer of $65,000 plus costs. Had the action gone to trial, the building surveyor would have had judgment entered against it for $16,000. The plaintiff received from the building surveyor $49,000 more than was later found to be its proper share of the loss. The question then arose as to the impact of this upon the orders to be made against the other concurrent wrongdoers. The answer was : none. The other concurrent wrongdoers were ordered to make payments to reflect their responsibility which, together with the surplus $49,000, would over top the amount of the plaintiff’s loss or damage. It was held that settlement at over value should not in principle operate differently from settlement at under value: Gunston at [65].

It seems that by skilful settlements a plaintiff can receive compensation for loss or damage that is greater than the loss or damage actually suffered by the plaintiff. S 32B cannot assist the non-settling defendants in this scenario as they cannot point to “damages previously recovered” by a plaintiff who has “ recovered judgment” against the settling party at over value.

Where the costs of an action are going to be enormous and a plaintiff is willing to exit the entire litigation for a reasonable sum, it seems possible for one defendant in multi-defendant litigation to settle for all defendants and then seek appropriate contribution from the other responsible parties. The Court of Appeal decision in Godfrey Spowers [2008] VSCA 208, suggests that at least where a settling wrongdoer has paid more than his proportionate liability, and has procured the release of the other concurrent wrongdoers, nothing in the Victorian analogue of CLA s.32A prohibits a concurrent wrongdoer, who settles an apportionable claim before judgment, from claiming contribution under our equivalent of the Law Reform Act in relation to the settlement sum. The key seems to be in the words “concurrent wrongdoer against whom judgment is given” in CLA s.32A and its analogues. It is only such a concurrent wrongdoer who cannot be required to contribute to the damages recovered or recoverable from another concurrent wrongdoer.

Alternatively, it is theoretically possible for one defendant who wants to settle to seek against the other defendants a declaration that their liability to a plaintiff is proportionate and to ask for a determination of what those proportions are21. But the practicalities of such an approach to further an individual settlement seem extraordinarily difficult.

Contractual rights to indemnity

Contractual rights to indemnity

Here one party has agreed to indemnify the other in relation to particular liabilities. The Planner has the benefit of a contractual indemnity from its parent , the Valuer , for any liability it incurs to third parties after 2006. Is this indemnity enforceable? If the law of New South Wales is to be applied, it would seem that the answer is in the affirmative : s.3A.

If the law of Queensland applies, three provisions of the CLA are or may be relevant : s.7(3) and (4) ; s.28(5); and s 32A, and it must be said there is no clear answer to the question.

The first, s 32A, provides that “subject to this part “ (Ch 2 Part 2) a concurrent wrongdoer against whom judgment is given in relation to an apportionable claim can not be required to contribute to the damages recovered or recoverable from another concurrent wrongdoer for the apportionable claim and can not be required to indemnify the other concurrent wrongdoer.

On their face, these words seem to mean that if judgment is given against the Valuer in relation to an apportionable claim, the Valuer can say to its subsidiary (and its insurer) that it cannot not be required to contribute to the damages recoverable by the Plaintiff from the Planner or to indemnify it for those damages.

Some commentators favour interpreting the references to “contribution” or “indemnity” in s.32A as being to entitlements under the Qld contribution statute, not under any applicable contract. However s.7 (3) would tend to suggest that s 32A embraces contractual indemnities, as s.7 (3) has the effect that Ch 2 Part 2 “prevent(s) the parties to a contract from making express provision for their rights, obligations and liabilities under the contract “and that this prohibition” extends to any provision of (the CLA) even if the provision applies to liability in contract”.

However there may be scope for the enforcement of contractual indemnities by reason of s.28(5) , which provides that a provision of Ch 2 Part 2 “ that gives protection from civil liability does not limit or otherwise affect any protection from liability given ….by another … law” . So a protection from civil liability to the Plaintiff given to the Planner by the law of contract, for example, may not be affected.

Anomalies

There are a number of other difficulties and anomalies in the provisions of Chapter 2, Part 2.

Mr Welford stated that the provisions had been “carefully framed to ensure that average consumers are protected in claims for negligent professional advice, giving rise to damages for which compensation might be apportioned”. The words “carefully framed” are questionable.

S. 28(3)(b) has the effect that the CLA does not apply to claims by consumers (that is, it does not apply to a claim “based on rights relating to … services … in circumstances where the … services … relate to advice given by a professional to the individual … other than for a business carried on by the individual … ”. So advice given (a) to individual lender who is not in the business of lending money or (b) to an individual investor to buy shares or other financial services will not be apportionable claims.

But there remains the apparent inconsistency between the effect of s.28(1)(b) and s.32F:

(a) A claim for economic loss or damage to property in an action for damages for contravention of s.38 of the Fair Trading Act is an apportionable claim: s.28 (1)(b). This should have the consequence that concurrent wrongdoers in relation to such a claim are liable only for an amount reflecting their responsibility: s.31.

(b) But s.32F abrogates the effect of making claims under the Fair Trading Act apportionable claims. s.32F provides that a concurrent wrongdoer in all claims for damages for contravention of the Fair Trading Act is severally liable for all the damages. This can hardly have been intended, in respect of advice given to professional lenders or investors. Their FTA claims will not be apportionable claims.

The second major difficulty concerns what appears to be the irreconcilability between s.32A (contribution not recoverable from a concurrent wrongdoer) and s.32H (concurrent wrongdoer may seek contribution from person not a party to the original proceeding).

The notion in s.32A, consistent with s.31, is that wrongdoers in apportionable claims only pay the amount the Court considers just, having regard to their responsibility for the loss. However, s.32H allows a concurrent wrongdoer to recover contribution “in another proceeding … from someone else in relation to the apportionable claim”. Beyond cases where one wrongdoer has a contractual indemnity against another, or whether liability of a wrongdoer is vicarious, this section appears to conflict with s.32A.

Footnotes

- Queensland Parliamentary Debates, 11 March 2003, 366 to 369.

- Godfrey Spowers [2008] VSCA 208 Ashley JA at [102] ; Reinhold [2008] NSWSC 187 [30] ; Dartberg Pty Ltd v Wealthcare Financial Planning Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1216 at [31] , Chandra v Perpetual Trustees Victoria Ltd [2007] NSWSC 694 at [111] .

- Woods v. De Gabriele [2007] VSC 177 at [43]

- Reinhold [2008] NSWSC 187 at [24]

- Shrimp v Landmark Operations Limited [2007] FCA 1468

- Atkins v. Interprac [2007] VSC 445 at [10] and [20].

- Ucak v Avante Developments [2007] NSWSC 367 at [35] – [39].

- HSD Co Pty Ltd v. Masu Financial Management (2008) NSWSC 1279 at [15] per Rothman J.

- Nemeth v. Prynew [2005] NSWSC 1296 at [27]

- Norwich Pharmacal Co v Customs and Excise Commissioners [1974] AC 133

- Computershare Ltd v Perpetual Registrars Ltd [2000] 1 VR 626 and Lenah Game Meats

[2001] HCA 63 at [103].

- Accounting Systems 2000 (Developments) Pty Ltd v CCH Australia Ltd (1993) 42 FCR 470 at 505—506.

- as in Podrebersek v Australian Iron & Steel Pty Ltd (1985) 59 ALR 529

- Reinhold [2008] NSWSC 187 at [43]

- Yates v Mobile Marine Repairs Pty Ltd [2007] NSWSC 1463 at [97]

- Chandra v Perpetual Trustees Victoria Ltd [2007] NSWSC 694 at [80]

- Reinhold at [53]

- Reinhold at [57]

- Pilmer v. Duke Group Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 165 at [74].

- McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Ltd [2000] HCA 65

- BHPB Freight [2008] FCA 1656

Having regard to the Dictionary definitions of the words “claim”, “duty” and “duty of care” in CLA s.28(1) it is clear that the Lenders causes of action against the Solicitors are for economic loss “in an action for damages arising from a breach of a duty of care”.

Having regard to the Dictionary definitions of the words “claim”, “duty” and “duty of care” in CLA s.28(1) it is clear that the Lenders causes of action against the Solicitors are for economic loss “in an action for damages arising from a breach of a duty of care”. The warranties in building case can be a useful contrast. A contract with a builder to build a house of a particular design involves the assumption of a number of contractual duties , including supplying material of adequate quality and in accordance with the specification , and carrying out the work itself with the care and skill to be expected of a skilled tradesman. However, in the standard case of a breach ( by the use of non-specified materials , or in a way inconsistent with the design drawings ) the complaint is not that the builder failed to exercise reasonable care and skill, but rather that it failed to supply what was contracted for.

The warranties in building case can be a useful contrast. A contract with a builder to build a house of a particular design involves the assumption of a number of contractual duties , including supplying material of adequate quality and in accordance with the specification , and carrying out the work itself with the care and skill to be expected of a skilled tradesman. However, in the standard case of a breach ( by the use of non-specified materials , or in a way inconsistent with the design drawings ) the complaint is not that the builder failed to exercise reasonable care and skill, but rather that it failed to supply what was contracted for.  Principles of apportionment

Principles of apportionment

Contractual rights to indemnity

Contractual rights to indemnity