Reminiscences of the Rockhampton Bar

Graeme Crow and Tony Arnold outlined the history of Trustee Chambers and the benefits of practising at the Rockhampton bar in issue 35 of Hearsay. It is always pleasing to read sympathetic accounts of Rockhampton. We are reminded with distressing regularity that after his visit in 1873 Anthony Trollope described it as the city of “sin, sweat and sorrow”, a calumny I first heard from the Christian Brothers who assured us that it was correct and that, accidents of birth being what they were, we would just have to learn to live with it.

However, flying in the face of the gale of public opinion I have often attempted to extol the virtues of the place during what may well have been its golden years, the 1960s and 1970s. They were the best of times because Rocky was then a proper city; a place with a heart, vibrant institutions and replete with characters. Supermarkets and political correctness were in the distant future.

In 1965 that exemplar of political incorrectness the redoubtable Rex Pilbeam was the Mayor. He had arrived in town in 1949, was elected Mayor in 1952 and was shot by his lover in June 1953 when he attempted to terminate their affair. The woman was charged with attempted murder and a couple of months later the Police Court heard that she had described Pilbeam to investigating officers as: “Poison … but oh, what sweet poison”.

Pilbeam’s career in local government hardly missed a beat. He was elected to ten consecutive three year terms as Mayor and spent some time with Queen Elizabeth II during her two hours at Rockhampton in 1954. I don’t know whether he upstaged Menzies’ performance of ten years later with a recitation of “I did but see her passing by …” however, had he thought of it, he may well have. In any case it was a pitifully short time given Her Majesty to appreciate the Mayor’s charms.

By 1965 Mr Justice Sheehy had been in Rockhampton longer than Rex Pilbeam, having been appointed Central Judge in 1947. And Mr N.F. Applin S.M. – who had been confronted with that Shakespearian description of Mayor Pilbeam in 1953 — was still the local Magistrate.

Then there was the Rockhampton Bar: Derrington and McGuire — followed in short order by Hall, Jones and Dodds.

Desmond Keith Derrington had graduated and been admitted to the Bar in 1954. A true son of Rockhampton he was highly regarded by my father. I was assured that “Des has a way with words” and that he “could get anyone off”, especially on a charge of rape. My father was not a lawyer but he was a part-time SP bookmaker and so (as Fitzgerald established) he must have known a thing or two.

Of course this was all a bit above my head. I was in my last year of secondary school and rape was something I knew nothing about. Furthermore I had no idea that creatures such as barristers existed. So Dad arranged an appointment for me to call on Des after school.

In 1965 Derrington’s chambers comprised a large, comfortable room in the Union Trustee building (now Trustee Chambers and described so well by Crow). The room opened onto a verandah overlooking the Fitzroy River beyond which the Berserker Mountains brooded over the city. By this time Derrington’s reputation was that of a formidable cross-examiner and a compelling advocate. I know that now. I didn’t know it then and, if I had, I may have approached our meeting with more apprehension. The mess of papers everywhere struck me as curious. Des was bright and cheerful — he was about 35 years old – and the lock of fair hair over his forehead bobbed about as he jumped from chair to desk to bookshelves in a valiant attempt to convey to me in one short, simple lesson what life as a barrister was all about.

Of course he failed. All I carried away was a mild sense of foreboding because of the law reports. Des had gesticulated airly at the piles of the current issues of the Queensland Reports and the All Englands and informed me that after a hard day in court a barrister had to read these things before going to bed. It sounded awfully hard.

Not long after that interview I was privileged to be articled to Mr Ewan Arthur Milford Palmer and Mr Desmond Errol Davey of Messrs Rees R. & Sydney Jones. Des Davey set me straight early on with the advice that barristers were the most impractical people of all time, wanting this and wanting that and having no idea what could be done and what couldn’t. He told me to watch out for them.

Mr Ewan introduced me to the delightful Fred McGuire. Freddie was the most amiable, imperturbable soul. He could be seen most days strolling casually along East Street in the direction of the Courts as the Post Office clock struck ten. My Master remarked to him once “Fred, don’t you think you’d better get along!”

To which Fred replied “Ah Mr Ewan, no need to rush. I’ll be saved by the drunks parade.”

McGuire’s chambers like those of Derrington were approached by a long, narrow stairway. But there the similarity ended. Fred’s was an internal room above the NAB in East Street. The walls were not adorned with any pictures as is the current fashion, save maybe for a Bank calendar and another from a local panelbeater, each opened at a glossy photograph for a month years in the past.

Fred may have had some kind of filing system but in the end it proved unfathomable even to him. Mr Ewan had sent him a brief to advise some years before I came on the scene. He discussed the matter with me and telephoned Fred on several occasions only to be constantly reassured that the advice was on the way. In those days a delay of a year or so did not seem to raise anyone’s ire. But, finally, I was sent over to see Fred with instructions that I should bring the advice back with me.

It was unusually hot. I arrived to see Fred at his desk, half glasses towards the tip of his nose as he read while his hair, parted in the middle, flipped up and down in the draft from an electric fan perched at arms length on a leaning tower of criss-crossed Weekly Law Reports. He greeted me with a grin as Mr Ewan had told him I was on the way and why.

“Danny” he confided, “I don’t know where the blessed brief is! I haven’t seen it for years — hope I haven’t lost it.”

So we rummaged about. Briefs in those days were not the masterful A4 volumes of today; most were a slim sheaf of papers folded in half and tied with pink tape, or a slim sheaf held together with a deadly split pin arrangement. The desk was covered with them well above head height and Fred had dug out a little canyon between them at which he did his current work. The same arrangements existed on the floor and such shelving as there was.

After shifting the debris of ages we found it. Fred beamed at me. He had soft, full dark brown eyes and an elegant nose. He was of Lebanese descent and at times he could look very biblical.

“Well” he said, with his distinctive wheezing giggle “better read it I suppose!” After a while he fluttered his eyes as he gazed into the distance. Then he took a foolscap sheet, folded a margin down the left side and began to write in red biro (couldn’t find the blue one at the time). He wrote a page and a half without hesitating then signed it. He had a sprawling but legible hand and my master said the advice was wonderfully lucid and to the point.

Before long Des Derrington not only enlightened me on the subject of defending rape cases but also taught me how to shave.

“Danny” he observed with considerable gravity as I bumbled away at my chin and neck one morning, “that is not the way to shave.”

The statement had an ex cathedra air about it and I felt quite the callow youth, which of course I was at the grand age of about eighteen years. We were in the male washrooms at the Springsure hotel. There were several other men present most of whom were policemen, graziers and lawyers — all lined up at the wash basins lathering away and gossiping and joking.

We were in Springsure for a case that had nothing to do with rape or my continuing education in the rites of manhood. It was about the ownership of cleanskin cattle impounded by the Stock Squad and suspected of being stolen. Derrington was briefed for the owners of Mantuan Downs station who claimed ownership. Alan Demack appeared for the owners of a neighbouring property. Several experienced cattlemen were there to give evidence about ‘the look’ by which cattle could be identified although unbranded. And of course we were all staying at the Springsure Hotel.

“You see Danny,” Des continued “your beard grows in certain directions, like the grain in a piece of wood. If you just draw the razor down … “ — he demonstrated — “then you are probably going with the grain and not getting a clean shave.”

He gave me that quizzical raised eyebrow look and, satisfied that I was paying attention, returned to the task.

“You must follow with an upward stroke.” Again he demonstrated, and I attempted to emulate his movements without slitting my throat.

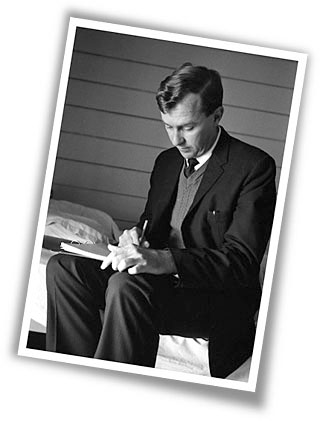

After breakfast and before we crossed the road to court I persuaded Des to let me take the accompanying photograph. Those who met him in later life as a Supreme Court Judge will have no difficulty recognising the dapper, youthful looking Des Derrington. He never really changed.

Over dinner that evening with a couple of our grazier clients and expert cattlemen I plied Des with questions about criminal cases. He obliged with a verbatim account of the cross examination in a recent rape case. As I would discover in later years all barristers really like doing this, and few could do it better than Derrington.

I was fascinated. That morning I had been taught to shave, and now I was having a sex education lesson. The Christian Brothers had never mentioned anything like this. It seemed to be a revelation to the cattlemen as well. A life on the range ridin’ fences had not really prepared them for such intimacies. They had huge hands with thick, calloused fingers from handling the reins or whips or hog tying, or something. And they nervously tugged at their ear lobes and stroked their chins as Des worked towards the climax of the cross examination and, when it came, and the prosecution case lay in tatters — they just about passed out with shock.

to be continued …

Dan Ryan