FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 91: Mar 2023, Reviews and the Arts

Editor: Nadia WheatleyPublisher: NewSouth BooksReviewed by Franklin Richards

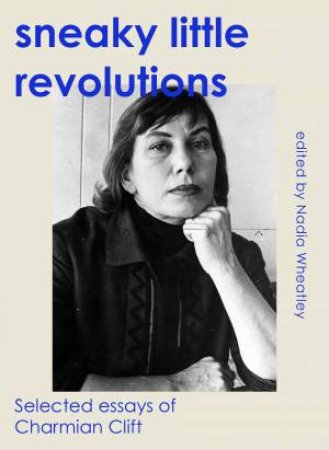

Charmian Clift stares from this book’s cover, her chin resting upon a ramrod arm and clenched fist, looking as defiant and strong as Rosie the Riveter. Even before reading a word of her prodigious body of work, you sense that she was an extraordinary woman. A revolutionary, born brave, who, unashamedly, blazed through life at a time when a woman was not expected to live unashamedly or to blaze.

For her twenty-five adult years, she somehow managed to combine her art, work, love and duty. That she managed to combine these competing elements at all, let alone for as long as she did, until her death by suicide in 1969, is a cause for celebration.

Clift’s life was one of diverse and intense experiences and achievements. There were setbacks of, course, but she kept at it. Editor, Nadia Wheatley, sets the scene, beautifully, in her introduction to Clift’s essays.

Born on 30 August 1923, in the last of a straggle of weatherboard workers’ cottages on the outskirts of the New South Wales coastal township of Kiama, Charmian Clift was bequeathed a double legacy by her birthplace. On the one hand, her consciousness was shaped by the wild beauty and freedom of living so close to the beach that there would be seaweed draped on the front fence of the family home after a storm. On the other hand, she grew up with a sense of living on the outside – at ‘the end, rather than the beginning of somewhere’. Rebellious, ambitious, and fiercely intelligent, she was desperate ‘to get out into the big bad world and do something better than anyone else could do’.

Clift achieved a lot. At just nineteen, she bore and was pressured to adopt out her illegitimate child, she served in the Australian Women’s Army Service, worked for Melbourne’s Argus newspaper, was dismissed for her affair with George Johnston, an older married colleague, and persisted in that partnership that would endure for twenty-three years and produce three children and thirty books.

The couple lived and wrote in England and on the Greek Islands of Kalymnos and Hydra before returning to Australia in 1964. By then, her husband had completed his classic work, My Brother Jack. Though a deeply collaborative work, and despite her own literary career and achievements, it was Johnston who was lauded. Clift, it appeared at the time, was destined ‘to be treated as her husband’s helpmate.’

The opportunity for Clift to disentangle her career from her husbands came in the form of an idea from a senior editor for the Melbourne Herald. He invited her to write some regular pieces for the paper. Johnston later noted that the editor ‘… explained that he was not looking for a women journalist, but a writer. The daily press needed some writing, real writing, from a woman’s point of view.’

Wheatley writes that ‘From her very first “piece”, the essayist found her voice: intelligent, conversational, and intensely personal.’ Charmian Clift’s ‘sneaky little revolutions’, as she once called them, had begun. For the next five years, she produced wonderful essays, published regularly in the Sydney Morning Herald and the Melbourne Herald.

What impresses when reading Clift’s essays is that, though written over half a century ago, they remain relevant. Some remind us of how things once were, others disclose how far we have come, or not come, while still others are marked by their prescience. That’s what impresses the reader, but what smacks, really smacks, is the sharpness of her observations and beauty of her writing. The essays deliver the sort of exquisite turn of phrase that checks the breath and brings a smile.

For example, ‘What are you doing it for’, says this about hubris and our inevitable end.

It is the most pretentious nonsense to believe that the work you do will live after you. It might, but then again it might not, and history will be the judge of that, not you. What most of us leave to posterity are only a few memories of ourselves, really, and possibly a few enemies. A whole human life of struggle, bravery, defeat, triumph, hope, despair, might be remembered, finally, for one drunken escapade.’

Clift had something smart to say about everything. She wrote about the big issues of the day such as conscription, American colonialism and Australia’s place in Asia. She wrote about social issues like ageing, the generation gap and antiquated licensing laws. She wrote movingly of her personal world, about caring for a dying partner, raising children and her happy childhood – ‘when you’re young it’s mostly summer. Endless. Golden’. She created sharply focused portraits of places, far away and close to home. Places like Hydra, central Australia and suburban Sydney.

Of North Queensland, my birthplace and home, she wrote.

People seem more like real people in the northland. Perhaps because there are so very few of them, and each one of the few has so much space to move in that everybody is quite distinct, individual, a figure in a landscape. It is not that the people are really larger than life, or even, I think, unduly eccentric. It is more the feeling that nobody in the north is anonymous.

Charmian Clift was a self-described ‘Yay-sayer’. This and her gusto for life has caused many to wonder whether she took her own life by accident or design. Whatever the truth of it, in her sneaky little revolutions, she has left a shimmering reflection of herself and her world.

For that she ought to be remembered, fondly, and thanked.