FEATURE ARTICLE -

Advocacy, Issue 93: Sep 2023

In Hunt Leather Pty Ltd v Transport for NSW [2023] NSWSC 840 (19 July 2023) a decision of Cavanagh J of the Supreme Court of New South Wales – that being a class action – the lead plaintiff shopkeepers affected by the construction of the Sydney Light Rail succeeded in proof of entitlement to damages in the tort of private (but not public) nuisance. The court found the alleged nuisance proved and the entitlement to recovery was unaffected by s 43A of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW), the analogue of s 36 of the Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld).The decision is instructive as to proof of nuisance by shopkeepers affected by construction of public infrastructure and the operation of statutory defences in relation thereto. Due to the length of the decision, we include below only the factual background and conclusory paragraphs, together with a summary thereof delivered by his Honour. The emphasis in bold is ours:

INTRODUCTION

- Attached to this judgment is a summary which was delivered orally on 19 July 2023 for the benefit of the parties and those members of the community who are interested in these proceedings. The summary contains extracts from this judgment. All of the passages in the summary are to be found in the judgment.

- These proceedings are representative proceedings pursuant to Part 10 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW) (“CPA”). The proceedings are pursued on behalf of the persons said to be affected by the construction and development of the Sydney Light Rail (“SLR”) between Circular Quay and Randwick/Kingsford in Sydney.

- As set out in paragraph 1 of the third further amended statement of claim filed on 26 October 2022, the proceedings are pursued on behalf of all persons:

- who or which:

- hold, or have held, an interest in land in the vicinity of the SLR; and

- have suffered loss or damage by reason of the defendant’s interference with their enjoyment of their interest in land (“the Private Nuisance Group Members”); and/or

- who or which have suffered a loss or damage as pleaded by reason of the defendant’s interference with public land through the carrying out of the SLR project (“the Public Nuisance Group Members”); and

- All of the persons who may come within the descriptions set out in paragraphs (a) and (b) are said to be “Group Members”.

- The defendant is a New South Wales Government agency constituted as a statutory corporation pursuant to s 3C of the Transport Administration Act 1988 (NSW) (“TA Act”) and, by operation of s 13A(1)(a) of the Interpretation Act 1987 (NSW) (“Interpretation Act”), is a statutory body representing the Crown pursuable by way of s 50(1)(c) of the Interpretation Act and/or s 5(2) of the Crown Proceedings Act 1988 (NSW).

- The defendant is the NSW Government agency which planned, designed and managed the processes leading towards the construction of the SLR, although it did not actually undertake the construction work.

- The powers and functions of the defendant are governed by the TA Act. As set out in s 3D of the TA Act, an objective of the defendant is “to plan for a transport system that meets the needs and expectations of the public”.

- The general functions of the defendant are set out in s 3E and Schedule 1 of the TA Act. These include:

- transport planning and policy, including for integrated rail networks, road networks, maritime operations and maritime transport and land use strategies for metropolitan and regional areas;

- the administration of the allocation of public funding for the transport sector; and

- the planning, oversight and delivery of transport infrastructure.

- Division 2A of Part 9 of the TA Act contains “special provisions relating to light rail”. These provisions include s 104O, pursuant to which the defendant may develop and operate light rail systems or facilitate their development and operation by other persons.

- The defendant says that it was exercising the powers conferred on it by s 104O when it was involved in the planning, development and design of the SLR prior to the commencement of the construction work.

- There are four lead plaintiffs, being:

- Hunt Leather Pty Ltd (“Hunt Leather”), which operates a retail leather goods business;

- Ms Sophie Hunt, who has been the Chief Executive Officer of Hunt Leather since approximately 2003;

- Ancio Investments Pty Ltd (“Ancio”), being the trustee of the unit trust known as the Ancio Unit Trust, which between May 2009 and April 2019 operated a restaurant business on Anzac Parade in Kensington; and

- Nicholas Zisti, who was the sole director of Ancio and operated and who had responsibility for the restaurant.

- After a short delay and some preliminary arguments, the hearing commenced on 7 November 2022 (an earlier hearing date had been vacated).

- The hearing concluded on 13 December 2022.

- The hearing which took place during that period was to determine:

- the liability of the defendant to the lead plaintiffs;

- the amount of damages (if any) which would be payable by the defendant to the lead plaintiffs; and

- agreed common questions.

- Although the legal representatives for the plaintiffs estimate that there may be thousands of people who fall within the class defined as Group Members, the initial hearing was only in respect of the lead plaintiffs. However, like all class actions, the purpose of the hearing was also to determine common questions which may impact on the entitlement of other Group Members to any damages.

- In this matter, there are particular difficulties with the potential common questions as, unlike some class actions where there may be a single cause of loss sustained by all members of the class, the causes of any loss suffered by Group Members are in dispute and may vary.

- Fundamentally, that is because there may be substantial differences between the impact that the construction of the SLR had on landholders and business owners at certain points along the route compared to others. This was demonstrated in the initial hearing because Hunt Leather occupied stores in what is described as Fee Zones 5 and 6 on George Street in the Sydney Central Business District (“CBD”), whereas Mr Zisti’s restaurant operated in Fee Zone 29 on Anzac Parade in Kensington.

- There may be some commonality in terms of what occurred outside Mr Zisti’s restaurant and the Hunt Leather stores but there are also some significant differences.

The Sydney Light Rail

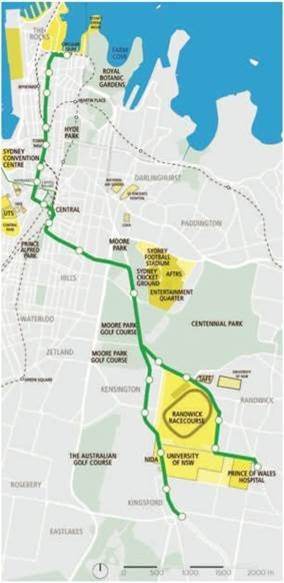

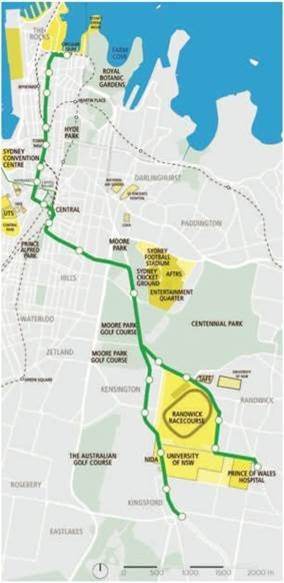

- The SLR is well-known to Sydneysiders. It constituted a major infrastructure development by the NSW Government. It commences at Circular Quay and runs through the heart of Sydney via one of Sydney’s main streets, George Street. It then proceeds up through dense and busy areas such as Surry Hills and along one of Sydney’s south-eastern thoroughfares, Anzac Parade, before branching off into two lanes, one from Centennial Park to Randwick along Alison Road and the other from Moore Park to Kingsford (via the University of New South Wales) along Anzac Parade.

- A map showing the SLR route is below:

- The main planning of the SLR commenced in 2012. The defendant determined that the SLR would be built and operated through a public and private partnership (“PPP”) with the entity appointed by the defendant being responsible for both the construction and the operation of the SLR for a period of 15 years. Under a PPP, the State enters into a project deed pursuant to which the other party in the partnership agrees to finance, design, construct commission, operate and maintain the asset which is built for a specified term (in this case, 15 years).

- The timetable proposed by the defendant allowed for a period of approximately two years of planning and development, with entry into a project deed in December 2014. In fact, this is what occurred. After significant investigation and planning, the defendant called for proposals. It selected a proponent (being Connecting Sydney, known as “CSY”), negotiated and then entered into a project deed on 17 December 2014 (“Project Deed”). CSY nominated a number of ALTRAC companies as the entities through which it wished to contract.

- The term OpCo is used in the Project Deed to identify the other party to the Project Deed i.e. ALTRAC. I will use OpCo and ALTRAC interchangeably in this judgment. At the same time as it entered into the Project Deed, ALTRAC entered into a design and construct contract (“the D&C contract”) with its nominated contractor, a joint venture between Acciona and Alstom (“the D&C contractor”). The O&M contractor was Transdev. In reality, the parties standing behind CSY were the same parties behind OpCo and the D&C contractor.

- The terms of the D&C contract were similar to the terms of the Project Deed. Obligations and entitlements imposed on OpCo through the Project Deed were thus passed down the line to the D&C contractor. The project was due to be completed by March 2019. It was supposed to be completed in stages or according to “fee zones”, thereby ensuring minimal disruption to businesses along the route. As it turned out, it was not completed until March 2020. On any view, the project was beset with problems and delays. The defendant and the D&C contractor fell into dispute, with the D&C contractor claiming a significant additional sum from the defendant.

- I am not privy to the details of that dispute, as there was only limited evidence about it adduced in these proceedings. I am told that the defendant ultimately paid the D&C contractor an additional $550 million.

- The D&C contractor was originally a party to these proceedings but it is no longer a party. I do not know why it was originally joined to the proceedings and why it is no longer a party, other than that there has been a settlement, which must in some way be referable to that payment.

The lead plaintiffs’ businesses

The Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store

- Hunt Leather was established in 1975 by John and Elizabeth Hunt. In 2015, it operated ten stores throughout Australia, some of which were branded stores selling only international brands, such as Longchamp and Rimowa.

- Much of the evidence was directed towards the interference with the Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store and the losses sustained by Hunt Leather arising from that interference. Whilst there was also evidence relating to the Hunt Leather store in the Queen Victoria Building (“QVB”) and, of course, the impact on Mr Zisti’s restaurant, the focus of the evidence was very much on how the SLR construction activities impacted the operation of the Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store. This may be because, on one view, the impact on the Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store was both obvious and direct.

- When compared to some of the other fee zones (in particular, Fee Zone 29), the Sydney CBD is densely populated by buildings, both new and old, retail shops, apartments, department stores, restaurants and food stores. Further, perhaps another reason why the focus of some of the evidence was on Fee Zone 5 and the Strand Arcade store was because only at the Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store (and not the QVB store) was the opening of the premises on the footpath adjacent to hoardings that were erected when the construction activity started.

- Hunt Leather had been operating its Strand Arcade store since 12 April 2013. Its flagship store was previously in the MLC Centre in Martin Place, which it had operated since 1975. The Strand Arcade is a prestigious arcade in Sydney running between George Street and Pitt Street Mall. The Strand Arcade is replete with boutique stores, luxury stores, original specialty stores and food stores.

- The Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store occupied the north-western corner of the arcade at ground level, with large doors opening onto George Street and also an internal entrance on the arcade side.

- The Strand Arcade store produced Hunt Leather’s highest turnover of anywhere in Australia. It sold Hunt Leather goods as well as branded goods, such as Longchamp products. It sold a variety of products such as briefcases, compendiums and folios.

- According to Ms Hunt, business had been increasing in the Strand Arcade. At least to a certain extent, this is reflected in the increase in turnover in the Strand Arcade store. The turnover in the 2014-15 financial year was 65% higher than it was for the 2013-14 financial year.

- The Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store remained open throughout the whole period of the SLR construction and remained open until, like all businesses, it was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, Hunt Leather moved from its George Street-facing store to a space further inside the Strand Arcade, where it now continues to operate.

The Hunt Leather QVB store

- Hunt Leather also operated a retail store in the QVB in Fee Zone 6. Fee Zone 6 covered George Street between Market Street and Park Street. The QVB is a large, grand building of important historical significance which runs between Market Street and Sydney Town Hall. Like the Strand Arcade, the QVB houses a range of shops selling luxury goods, food, clothes and accessories (amongst other things).

- The lower ground level of the QVB forms part of the pedestrian walkway which runs from underneath the Myer building on the corner of Market and George Streets to Town Hall train station. Town Hall station is situated underneath Sydney Town Hall, which is across the street from the southern end of the QVB.

- Hunt Leather operated a Longchamp branded store in the QVB. That store closed in around November 2018. According to Ms Hunt, its closure was forced due to the inability of Hunt Leather to continue to support it, both because of the impact of the SLR construction activities in Fee Zone 6 and because Hunt Leather could no longer fund the QVB store using the profits of the Strand Arcade store.

- Longchamp is an international luxury goods brand. It is a French-owned company. Longchamp entered into an agreement with Hunt Leather to enable Hunt Leather to operate three stores in Australia selling only Longchamp goods. The agreement with Longchamp was not an exclusive agreement, in the sense that Longchamp bags and accessories were also sold in other stores in Sydney.

- The QVB store was on the ground level of the QVB. The entrance to the store was inside the QVB but it had a window or shopfront which faced George Street.

Mr Zisti’s restaurant

- Mr Zisti’s restaurant was situated on the eastern side of Anzac Parade at 1/240-268 Anzac Parade, Kensington (in Fee Zone 29). Mr Zisti operated his business through a corporate structure, as follows:

- from about May 2009 until April 2019, Mr Zisti was the sole director of Ancio and operated a restaurant business;

- from about May 2009 to July 2011, Ancio operated the restaurant premises as a Thai restaurant known as “In the Mood for Thai”. At that time, Mr Zisti worked in the business;

- from about 4 July 2011 until July 2018, another Thai restaurant (“Khing Thai”) operated from the restaurant premises;

- from about June 2013 to June 2014, Ancio operated a coffee cart outside the restaurant premises known as Giddy Up Expresso Bar (“Giddy Up”); and

- from about August 2018 to April 2019, an Italian restaurant (“Sugo Pasta Bar”) operated from the restaurant premises. During this time, Mr Zisti had a hands-on role in managing the business and operating the front-of-house.

- As his financial records show, Mr Zisti had been developing his business over the five years prior to the commencement of construction of the SLR. In the year before the construction commenced, his profits had reached better than ever levels at $149,000.

- There is no dispute that the SLR construction commenced in Fee Zone 29 on 7 May 2016. Occupation of Anzac Parade in Fee Zone 29 ended on 26 June 2019. Mr Zisti claims that the restaurant was impacted throughout this whole period, such that his entitlement to losses amounts to the diminution of sales or the net profit that he would have generated but for the SLR construction activities.

- In 2018, Mr Zisti closed his Thai restaurant due to low sales and opened a pasta bar instead. He says that he did so because of the impact of the SLR construction works. The pasta bar was not a success. He did not renew the lease in 2019; he says this was because he was not making any money from the venture.

THE POSITION OF THE PARTIES

- There is no claim that the noise and disruption caused by the SLR, once operational, constitutes a nuisance. Rather, the acts constituting the nuisance are said to have occurred during the construction of the SLR.

- Further, the plaintiffs do not complain about the conduct of the defendant during the period when construction was being undertaken (as the defendant did not undertake the construction work). The conduct of the defendant of which the plaintiffs complain is the conduct prior to construction, during the design, planning and contract negotiation phases of the project.

- This judgment will necessarily involve a consideration of complex legal issues and the interpretation of many construction-related documents, including an extensive project deed.

- As noted, the plaintiffs include the four lead plaintiffs. As lead plaintiffs, their names appear on the pleadings.

- The plaintiffs pursue only one cause of action. It is a cause of action in nuisance, both private and public. Private nuisance is a different legal concept from public nuisance but, in some respects, it gives rise to a consideration of the same principles. Nuisance is a tortious remedy. It is different from negligence, albeit there is a dispute between the parties about the extent to which the plaintiffs can establish nuisance without establishing some failure to take care on the part of the defendant.

- The essential proposition advanced by the plaintiffs is that during the construction of the SLR, the members of the class were subject to a nuisance in the sense that their rights, enjoyment and occupation of their properties were subject to an interference arising from the construction activities which was substantial and, if it is necessary to so find, unreasonable. As may be expected, the law does not merely permit any home or business owner to claim damages from a party who in some way created an interference by way of construction activities. To do so would impede the ability and entitlement of both private citizens and the government to undertake ordinary construction work, such as building and roadworks.

- In order to succeed in an action such as this, it will be necessary for the plaintiffs to establish that there was interference with their land (or the land that they occupied) at such a level as to constitute a legally actionable nuisance and, further, that the defendant should be liable for that nuisance.

- In this case, the plaintiffs submit that the nuisance was constituted both by the nature of the activities (which involved heavy construction machinery, vibrations, noise and dust, the presence of hoardings and the general restriction of pedestrian and vehicular movement) and the length of time that the work was being conducted outside their respective premises.

- Issues arise as to whether nuisance must necessarily involve construction activities being performed adjacent to the premises, or whether nuisance can be constituted by (for example):

- the erection of barricades on a roadway some distance from a shop, which might deter potential customers from walking past the shop;

- the placement of hoardings and barricades in the middle of the road when the entrance to the shop is not on the road but inside an adjacent building (i.e. inside the QVB); or

- the blockage by hoardings of the line of sight of a shopfront window from the other side of the road.

- The plaintiffs say that although the defendant did not actually do the physical construction work, it is personally responsible for the nuisance because it was the statutory authority which developed, procured, planned and organised the work. Further, they say that the nuisance arose because of the defendant’s failures in the planning, design and contracting phase (up to December 2014).

- The plaintiffs submit that if the defendant is liable in nuisance, then it is liable to pay damages to the lead plaintiffs.

- Damages are compensatory. If their claim is successful, the plaintiffs are entitled to be put back into the position they would have been in if not for the tortious conduct. That necessarily involves a consideration of whether and how the activities giving rise to the nuisance caused the lead plaintiffs to suffer loss (including loss of amenity).

- Ms Hunt and Mr Zisti also claim personal losses in the nature of damages for inconvenience and hurt arising from the public nuisance.

- The defendant’s response to these claims is to:

- deny that there has been any nuisance, whether private or public. The defendant submits that the plaintiffs have not established the elements of the tort of nuisance. They say this for a number of reasons, including that, whilst not disputing the essential proposition that noise, dust and construction work would and did have an impact on adjoining businesses:

- the interference was not substantial and unreasonable, highlighting that, on the defendant’s case, it is necessary for the plaintiffs to establish that the defendant failed to take reasonable care (as those terms are understood and informed, having regard to the relevant case law); and

- it could not be liable in nuisance because the interference was an inevitable consequence of the SLR construction;

- rely on s 43A of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) (“CLA”). That is, the defendant says that it has statutory protection in respect of this type of action against it; and

- rely generally on its role as a statutory corporation and, in particular, s 141 of the Roads Act 1993 (NSW) (“Roads Act”) as a defence to the alleged public nuisance.

- The case is conceptually difficult because the plaintiffs seek to rely on the way in which the construction activities were undertaken during the period of construction work for the purposes of establishing the nuisance, but they only seek to rely on their criticisms of the defendant’s conduct for the period up until the Project Deed was entered into in December 2014 (before the construction actually started). In these circumstances, there has been limited exploration of what actually happened during the course of the construction. Indeed, the defendant did not adduce any evidence of what actually happened during the SLR construction. The plaintiffs adduced evidence from one of their experts (Mr Mark Griffith) as to the cause of the prolonged periods of construction in the individual fee zones.

- The amount of loss said to have been caused by the nuisance is also in dispute. This is because, on the defendant’s case, there were other factors impacting the profitability of the Hunt Leather business and Mr Zisti’s restaurant, aside from the SLR construction. An example in respect of Hunt Leather is the increased competition in the luxury goods market. An example in respect of Mr Zisti’s restaurant is the change in parking restrictions on the street outside the restaurant.

- The case was prepared and presented in a thorough, competent and efficient manner by the parties. However, the evidence is extensive and the issues are complex. The combined submissions of the parties comprised over 1000 pages. The volume of material relied upon and the detail to which the parties descended in their efforts to refute the opposing case was extraordinary. The expert reports, when combined, amount to more than ten volumes of material. At times, it felt like this case was more a construction dispute than a claim in nuisance.

- At least according to the parties, there could be little doubt as to the correctness of their positions. Alas, the outcome of litigation does not permit a draw.

- It is important to observe that there are really two questions which arise in this hearing, as far as the plaintiffs are concerned:

- subject to any defences available to the defendant, was the interference to the lead plaintiffs’ properties such as to constitute an actionable nuisance? and

- should the defendant be liable for such a nuisance?

- I should say that there is some merit in the defendant’s suggestion that this is not a particularly apt vehicle for a class action. Whilst it is possible to answer some common questions, as will be apparent from consideration of the lead plaintiffs’ properties and businesses and the interference said to have been caused by the SLR construction, the nature and extent of interference with properties along the SLR route would vary significantly.

- For example, it does not seem to me that the following circumstances in and of themselves (that is, without some other matters or factors giving rise to interference with the use and enjoyment of the property), would be sufficient to be an actionable nuisance:

- the permanent closure of a section of George Street to vehicular traffic;

- the changing of parking restrictions; and

- the fact, if established, that less vehicles or people might have travelled along the road at any particular point.

- Questions of proof loom large for a number of different reasons.

- At the very beginning of the case, Mr Miller, on behalf of the defendant, submitted that the evidence adduced by the plaintiffs would not satisfy the Court of the fundamental proposition advanced by them, being that the defendant’s failures in planning and procurement caused a substantial delay and prolongation of the construction activities. Even though the occupation of individual fee zones was prolonged for periods of two or three times of what was initially anticipated, he submitted that this case would not provide an answer to members of the community as to why that occurred.

- Mr Miller submitted that it was not up to the defendant to prove why the construction activities took so long, such that the defendant would not be adducing evidence to explain the delay. Indeed, the defendant’s programming expert, Mr McIntyre, did not address the cause of the delay in his evidence, albeit he was critical of the methodology adopted by the plaintiffs’ expert, Mr Griffith.

- At the very end of the case, I again asked Mr Miller what caused the delay, if what was asserted by the plaintiffs did not. He gave essentially the same answer, being that the plaintiffs had not proved what caused the delay and it was not up to the defendant to establish the reason for the delay. As Mr Owens added after Mr Miller, there could be many causes, particularly in relation to the design decisions made by the D&C contractor.

- As I perhaps indicated during exchanges, I found it a little surprising that at the end of a case involving a government agency and thousands of members of the community who were affected by prolonged construction activities, the Court would be left uninformed about the cause of such a delay.

- In assessing the sufficiency of evidence, it is permissible to draw inferences and, of course, have regard to the power of each party to adduce evidence. The principle in Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63; (1774) 98 ER 969 applies. That is, evidence is to be weighed according to the capacity of a party to adduce it. One of the features of this case is that the parties obviously made forensic decisions as to the evidence which would be adduced. The plaintiffs prepared expert evidence on defined issues. The defendant opted to respond to some (but not all) of those opinions and did not seek to explain through additional evidence other issues, such as causation.

- Further, if a failure to take care is relevant, the parties are at odds about who bears the onus of establishing failure to take care. The plaintiffs’ position is that the exercise of reasonable care is not relevant to their primary cases. If it is relevant, the defendant bears the onus of establishing that it took care. The plaintiffs have not pleaded the existence or breach of any duty of care, although they refer to casually significant failures by the defendant.

- There is an issue as to who bears the onus of proof in establishing that the interference with the plaintiffs’ use of their land was inevitable in circumstances in which the defendant maintains that it was a statutory authority acting in accordance with the authority given to it.

- Finally, the plaintiffs maintain that the s 141 Roads Act defence to the claim in public nuisance is not maintainable, unless the defendant establishes that it complied with the conditions of the consent granted by the Roads and Maritime Services (“RMS”) on 2 October 2015. The plaintiffs nominate some conditions with which they say the defendant did not comply but then assert that it is up to the defendant to prove that it did so comply. The defendant asserts that the onus would be on the plaintiffs to prove that it did not comply with the conditions stipulated by the RMS.

- Generally, it would be preferable if cases were not decided on onus of proof issues. However, having regard to the way in which this case was pursued and defended, who proved what may be important.

The pleadings

- During the hearing, there was considerable focus on the pleaded case, particularly by the defendant. The plaintiffs perhaps took a broader approach to the pleadings.

- I granted leave to the plaintiffs to file a third further amended statement of claim on 24 October 2022. The final version of the statement of claim was filed on 26 October 2022. On 24 October 2022, I also granted leave to the plaintiffs to file a further amended reply. The final version of the defence was filed on 7 November 2022. The final version of the reply relied upon by the plaintiffs was filed on 17 November 2022.

- It is not necessary to consider earlier versions of the pleadings. I will thus refer to the third further amended statement of claim as “the Statement of Claim”, the amended defence as “the Defence” and the further amended reply as “the Reply”.

- The pleaded background is not in dispute. The plaintiffs do not plead the existence of a duty of care, the risk of harm or any breach of duty. Indeed, in the Reply, the plaintiffs plead that “these proceedings do not concern whether the Defendant had a duty of care or breached its duty of care.”

- Having set out the background to the commencement of the construction activities, the plaintiffs plead that there were delays in the Civil Works caused by the defendant. It is paragraphs 12(a)-(f) and 13-14(d) of the Statement of Claim which give rise to the central factual dispute in these proceedings.

- I summarise those paragraphs as follows:

- in March and May 2015, the D&C contractor advised the defendant that it had received guidelines from Ausgrid as to its requirements for the treatment of utilities along the SLR route;

- the Ausgrid guidelines differed significantly from the approach to utilities, which had been developed and agreed between the defendant and the D&C contractor (as recorded in Schedule F8 to the relevant project documentation);

- the new Ausgrid guidelines resulted in a substantial change to the scope of the project, leading to an estimated delay of over two years and four months and an estimated additional cost of around $426 million in civil construction works;

- a substantial cause of the Ausgrid scope changes was the defendant’s failure to finalise agreements with stakeholders, such as utility providers (including Ausgrid) and local councils, regarding the treatment of utility assets prior to entry into the Project Deed;

- during the course of the civil construction works, the defendant issued the D&C contractor with approximately 60 directions to change the scope of work (“project scope changes”);

- a substantial cause of the project scope changes was the failure by the defendant to effectively plan and procure the project between 2011 and 2014;

- during the course of the civil construction works, the D&C contractor encountered many unknown utilities which had the effect of prolonging the occupation of Fee Zones 5, 6 and 29 (“utilities prolongation”);

- the substantial cause of the utilities prolongation was that the defendant had entered into the Project Deed on terms that allowed the D&C contractor relief under the Project Deed and allocated no risk in respect of unknown utilities to the D&C contractor, in circumstances where unknown utilities were likely to be encountered (“the contracting conduct”);

- after the commencement of the construction, the defendant made repeated public statements to the effect that the project would be completed by 2019;

- the delays in the completion of the project and, alternatively, the prolonged occupation of individual fee zones was caused by delays during the civil construction works phase of the project; and

- each of the Ausgrid scope changes, the project scope changes and the contracting conduct were a substantial cause of the Civil Works delay, which was caused by the defendant’s conduct in:

- failing to finalise agreements with stakeholders, such as utility providers including Ausgrid and local councils, prior to entry into the Project Deed;

- failing to effectively plan and procure the project between 2011 and 2014; and

- engaging in the contracting conduct.

- Further, the plaintiffs plead that:

- there was a substantial delay in the completion of the overall project, or a delay in the planned occupation of the individual fee zones during the undertaking of the Civil Works; and

- that substantial delay was caused by the defendant’s conduct prior to commencement of the Civil Works by:

- failing to enter into appropriate agreements prior to entry into the Project Deed; and

- failing to effectively plan and procure the project prior to entry into the Project Deed and, alternatively, engaging in what it pleads as the contracting conduct.

- The plaintiffs then plead that, through its conduct in authorising or permitting the construction of the project and/or causing the Civil Works delay, the defendant caused a substantial and unreasonable interference with the plaintiffs’ and all Group Members’ enjoyment of their respective interests in land located in the vicinity of the project.

- Further, the plaintiffs then plead that through the conduct to which I have referred, the defendant has caused substantial and unreasonable disruption or inconvenience to the public in the exercise of public rights (namely, by the damage to and obstruction of roadways and footpaths, as well as road closures and the direction of hoardings) (“the public nuisance”).

- Put simply, by their pleadings, the plaintiffs allege that there were failures in the planning and procurement phase of the SLR and that those failures led to excessive delays in the construction works, thereby giving rise to a substantial and unreasonable interference with their properties.

….

CONCLUSION

- The first and third plaintiffs have succeeded, although Hunt Leather has only succeeded in respect of the Strand Arcade store. In my view, the interference with the Strand Arcade store and Mr Zisti’s restaurant was substantial and unreasonable for a period. The defendant is responsible for such interference because it created the state of affairs which led to the extended period of interference in circumstances in which the harm was foreseeable and, indeed, predictable.

- The defendant sought to minimise the interference with the businesses along the SLR route through its fee zone strategy but its fee zone strategy failed for the reasons I have identified.

- The defendant may have been exposed to additional costs but the persons who ended up bearing the costs of the prolonged construction activity in the fee zones were some of the business owners along the light rail route. They had been promised minimal disruption and a staged process of construction, which would have seen them exposed to the construction activities for months, rather than years.

- On any view, the original projections by the defendant were optimistic and not soundly based. I have thus allowed a longer period than that originally projected as being reasonable. There was obviously a degree of imprecision in trying to work out the point at which the interference with the businesses (which commenced when the construction work commenced) became unreasonable. I have relied on the opinion of the only expert who really attempted to undertake the analysis, Mr Griffith, in this regard. I have also accepted Mr Griffith’s opinion as to the cause of the prolonged period of construction in Fee Zones 5, 6 and 29.

- There is no alternative opinion or alternative evidence. There are merely assertions that Mr Griffith’s analysis is flawed.

- I have rejected the defendant’s statutory authority defence of inevitability.

- Further, I have found that s 43A of the CLA does not apply in the circumstances of this case.

- I have also rejected the plaintiffs’ claims in public nuisance.

- Those findings may assist going forward, bearing in mind that my determination only relates to two members of the class and three (out of 31) fee zones. However, it seems to me that there remains a significant problem in applying my findings about substantial and unreasonable interference to all members of the class. To the extent that this judgment, through the common questions and my findings in respect of the lead plaintiffs, is intended to provide a basis for the assessment of entitlements of other members of the class, I emphasise these matters:

- the reason that Hunt Leather and Ancio have succeeded is, in part, that they operated small businesses which were highly susceptible to the effects of construction activities without any means of reducing the impact. It is not difficult to understand how a small boutique luxury goods store which opened directly onto the construction works would suffer because of those works. It is not difficult to understand how a small specialist restaurant which relied on the amenity of its premises would suffer as a result of construction activities happening right outside its front door;

- however, the position may be different with other businesses. Mere proximity to the construction works does not establish substantial interference, no matter what the period of interference, as I have found in respect of the Hunt Leather QVB store. Many businesses may have been affected by the construction of the SLR in ways which would not constitute a nuisance, despite some diminution in profitability flowing from the construction of the SLR; and

- it must be remembered that the defendant was a statutory authority and was trusted with the responsibility of improving public transport in Sydney. Infrastructure development will always result in some impact on businesses in the relevant area and changes to an area caused by infrastructure development may have a detrimental effect on businesses. I do not consider that persons would have an actionable nuisance merely based upon factors such as:

- the closure of a road to vehicular traffic;

- changes in parking restrictions, such as parking being prohibited outside a business;

- changes in traffic conditions, resulting in a reduction in vehicular traffic;

- reductions in pedestrian traffic;

- premises becoming dusty in ways which could be relieved through self-help measures, such as by cleaning; and

- line of sight restrictions.

- Nuisance has been established in this matter by a combination of factors, particularly having regard to the way in which the construction activity impacted upon the business activities of the lead plaintiffs.

- It follows that the fact that persons were operating businesses adjacent to the SLR route during the period of construction does not, of itself, give rise to any cause of action on their part. More is required.

- The fact that these are representative proceedings does not alter the legal principles which apply. As I said at the outset, this is not a particularly apt vehicle for a class action, albeit as I have identified, some of the issues might be common and have been determined by this judgment. Going forward, there will need to be a process or mechanism developed for the determination of both entitlement and loss.

- My preliminary view is that referees (who are subject to the Court’s oversight) should be appointed to determine outcomes based on guidelines and parameters. Suffice to say, any system which involves each Group Member being required to spend vast sums on quantum experts and have extensive reports prepared for the purposes of assessing their loss (as the lead plaintiffs have done through the funder) must be unworkable.

- The lead plaintiffs, Hunt Leather and Ancio, are entitled to succeed. The other lead plaintiffs, Ms Hunt and Mr Zisti, are not.

- There will need to be another short hearing in order to:

- finalise damages for the lead plaintiffs;

- determine a process going forward; and

- consider whether there might be any other common questions which could be answered.

- I will list the matter for further directions.

….

**********

SUMMARY OF JUDGMENT

This Summary was delivered orally on 19 July 2023.

Introduction

- These proceedings are representative proceedings pursuant to Part 10 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW) (“CPA”). The proceedings are pursued on behalf of the persons said to be affected by the construction and development of the Sydney Light Rail (“SLR”) between Circular Quay and Randwick/Kingsford in Sydney.

- The defendant is the NSW Government agency which planned, designed and managed the processes leading towards the construction of the SLR, although it did not actually undertake the construction work.

- There are four lead plaintiffs, being:

- Hunt Leather Pty Ltd (“Hunt Leather”), which operates a retail leather goods business;

- Ms Sophie Hunt, who has been the Chief Executive Officer of Hunt Leather since approximately 2003;

- Ancio Investments Pty Ltd (“Ancio”), being the trustee of the unit trust known as the Ancio Unit Trust, which between May 2009 and April 2019 operated a restaurant business on Anzac Parade in Kensington; and

- Nicholas Zisti, who was the sole director of Ancio and operated and who had responsibility for the restaurant.

- The hearing which took place during in November to December 2022 was to determine:

- the liability of the defendant to the lead plaintiffs;

- the amount of damages (if any) which would be payable by the defendant to the lead plaintiffs; and

- agreed common questions.

- Although the legal representatives for the plaintiffs estimate that there may be thousands of people who fall within the class defined as Group Members, the initial hearing was only in respect of the lead plaintiffs. However, like all class actions, the purpose of the hearing was also to determine common questions which may impact on the entitlement of other Group Members to any damages.

- In this matter, there are particular difficulties with the potential common questions as, unlike some class actions where there may be a single cause of loss sustained by all members of the class, the causes of any loss suffered by Group Members are in dispute and may vary.

- Fundamentally, that is because there may be substantial differences between the impact that the construction of the SLR had on landholders and business owners at certain points along the route compared to others. This was demonstrated in the initial hearing because Hunt Leather occupied stores in what is described as Fee Zones 5 and 6 on George Street in the Sydney Central Business District (“CBD”), whereas Mr Zisti’s restaurant operated in Fee Zone 29 on Anzac Parade in Kensington.

- The main planning of the SLR commenced in 2012. The defendant determined that the SLR would be built and operated through a public and private partnership (“PPP”) with the entity appointed by the defendant being responsible for both the construction and the operation of the SLR for a period of 15 years.

- The timetable proposed by the defendant allowed for a period of approximately two years of planning and development, with entry into a project deed in December 2014. In fact, this is what occurred. After significant investigation and planning, the defendant called for proposals. It selected a proponent (being Connecting Sydney, known as “CSY”), negotiated and then entered into a project deed on 17 December 2014 (“Project Deed”). CSY nominated a number of ALTRAC companies as the entities through which it wished to contract.

- At the same time as it entered into the Project Deed, ALTRAC entered into a design and construct contract (“the D&C contract”) with its nominated contractor, a joint venture between Acciona and Alstom (“the D&C contractor”). In reality, the parties standing behind CSY were the same parties behind ALTRAC and the D&C contractor.

- The terms of the D&C contract were similar to the terms of the Project Deed. Obligations and entitlements imposed on ALTRAC through the Project Deed were thus passed down the line to the D&C contractor. The project was due to be completed by March 2019. It was supposed to be completed in stages or according to fee zones, thereby ensuring minimal disruption to businesses along the route. As it turned out, it was not completed until March 2020.

- The D&C contractor was originally a party to these proceedings but it is no longer a party. I do not know why it was originally joined to the proceedings and why it is no longer a party, other than that there has been a settlement.

- The Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store remained open throughout the whole period of the SLR construction and remained open until, like all businesses, it was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Hunt Leather also operated a retail store in the QVB in Fee Zone 6. Fee Zone 6 covered George Street between Market Street and Park Street.

- Hunt Leather operated a Longchamp branded store in the QVB. That store closed in around November 2018. According to Ms Hunt, its closure was forced due to the inability of Hunt Leather to continue to support it, both because of the impact of the SLR construction activities in Fee Zone 6 and because Hunt Leather could no longer fund the QVB store using the profits of the Strand Arcade store.

- Mr Zisti’s restaurant was situated on the eastern side of Anzac Parade in Kensington (in Fee Zone 29).

- In 2018, Mr Zisti closed his Thai restaurant due to low sales and opened a pasta bar instead. He says that he did so because of the impact of the SLR construction works. The pasta bar was not a success. He did not renew the lease in 2019; he says this was because he was not making any money from the venture.

The position of the parties

- There is no claim that the noise and disruption caused by the SLR, once operational, constitutes a nuisance. Rather, the acts constituting the nuisance are said to have occurred during the construction of the SLR.

- Further, the plaintiffs do not complain about the conduct of the defendant during the period when construction was being undertaken (as the defendant did not undertake the construction work). The conduct of the defendant of which the plaintiffs complain is the conduct prior to construction, during the design, planning and contract negotiation phases of the project.

- The plaintiffs pursue only one cause of action. It is a cause of action in nuisance, both private and public.

- The essential proposition advanced by the plaintiffs is that during the construction of the SLR, the members of the class were subject to a nuisance in the sense that their rights, enjoyment and occupation of their properties were subject to an interference arising from the construction activities which was substantial and, if it is necessary to so find, unreasonable. As may be expected, the law does not merely permit any home or business owner to claim damages from a party who in some way created an interference by way of construction activities. To do so would impede the ability and entitlement of both private citizens and the government to undertake ordinary construction work, such as building works and roadworks.

- In this case, the plaintiffs submit that the nuisance was constituted both by the nature of the activities (which involved heavy construction machinery, vibrations, noise and dust, the presence of hoardings and the general restriction of pedestrian and vehicular movement) and the length of time that the work was being conducted outside their respective premises.

- The plaintiffs say that although the defendant did not actually do the physical construction work, it is personally responsible for the nuisance because it was the statutory authority which developed, procured, planned and organised the work. Further, they say that the nuisance arose because of the defendant’s failures in the planning, design and contracting phase (up to December 2014).

- The defendant’s response to these claims is to:

- deny that there has been any nuisance, whether private or public. They say this for a number of reasons, including that, whilst not disputing the essential proposition that noise, dust and construction work would and did have an impact on adjoining businesses:

- the interference was not substantial and unreasonable, highlighting that, on the defendant’s case, it is necessary for the plaintiffs to establish that the defendant failed to take reasonable care (as those terms are understood and informed, having regard to the relevant case law); and

- it could not be liable in nuisance because the interference was an inevitable consequence of the SLR construction;

- rely on s 43A of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) (“CLA”). That is, the defendant says that it has statutory protection in respect of this type of action against it; and

- rely generally on its role as a statutory corporation and, in particular, s 141 of the Roads Act 1993 (NSW) (“Roads Act”) as a defence to the alleged public nuisance.

- The case was prepared and presented in a thorough, competent and efficient manner by the parties. However, the evidence is extensive and the issues are complex.

- At least according to the parties, there could be little doubt as to the correctness of their positions. Alas, the outcome of litigation does not permit a draw.

- It is important to observe that there are really two questions which arise in this hearing, as far as the plaintiffs are concerned:

- subject to any defences available to the defendant, was the interference to the lead plaintiffs’ properties such as to constitute an actionable nuisance? and

- should the defendant be liable for such a nuisance?

- In their closing submissions, the plaintiffs put their case in three alternative ways. As they say, the primary case is Case A, which they say requires them only to establish that the interference with their premises was substantial, giving rise to an entitlement to damages from the time when the construction work commenced. They advance alternative cases in the event that they are unsuccessful in their primary case.

Consideration of evidence and the plaintiffs’ complaints

- In the pleadings, throughout the conduct of the hearing and during submissions, the parties referred to the “utilities risk”. The utilities risk is also referred to in many documents relied upon by the parties.

- Generally, the utilities risk was the potential for problems to arise during the SLR construction from the presence of utilities along the SLR route. As I will identify, at the time of entry into the Project Deed, it was known that there were many utilities along the route which would need to be treated in order for construction to proceed. It was also expected that there would be more utilities which were not known to exist at the time of entry into the Project Deed but which would be discovered during the course of the construction.

- The utilities risk was the risk of delay and additional costs arising from the need to treat utilities and the discovery of previously unknown utilities.

The planning and development of the SLR

- The judgment contains an extensive analysis of the pre-Project Deed documents. Only my conclusions from those documents are contained in this summary.

Conclusions from planning documents

- A number of things are clear from the pre-Project Deed documents, including that:

- the defendant’s original intention was to deliver the project through an extensive Early Works contract, which would include the utilities treatments followed by a separate Civil Works contract. Over the pre-Project Deed period, particularly in 2014, that plan changed such that the defendant decided that the utilities treatment works would form part of the Civil Works contract and the Early Works contract would be limited to six key intersections (and would include utilities treatments);

- the defendant was aware of the significant risk to business owners along the SLR route arising from the construction activities. It was aware that the construction of the SLR would have a significant impact on businesses. It was aware of the Gold Coast experience in which 15% of businesses along that route had failed during the construction period. It was aware that it needed to minimise interference with local businesses as far as possible and that doing so would be critical to the viability of the businesses;

- the defendant was well aware of the utilities risk. It was one of the primary risks associated the project, particularly bearing in mind that the project would require excavation of one of Sydney’s busiest streets (being George Street);

- at the time of entry into the Project Deed, the defendant was aware that it had not yet discovered all utilities along the route and that there would be unknown utilities. It was aware that the discovery of unknown utilities could delay the Civil Works. It was aware that its investigation into utilities was more thorough along Route A (which included George Street) than other areas, such as Anzac Parade. It was aware that the discovery of unknown utilities would delay the progress of the construction works. It was aware that 30% of the utilities being discovered through the trenching contract were unknown utilities;

- at the time of entry into the Project Deed, the defendant was aware that no agreement was in place with the major provider of utility services, Ausgrid, or indeed, other utility providers (such as Sydney Water) as to how their utilities could be treated. This was identified by the defendant as another risk to the performance of the Civil Works, that is, the risk remained that Ausgrid might require different treatment methods from those identified in the Project Deed. This is what the D&C contractor said occurred and what led to a substantial claim for compensation from the D&C contractor;

- the defendant had been warned by Ausgrid that the defendant’s own plans, in terms of cost and timing in dealing with the utilities, was likely to be a significant underestimation. Ausgrid had warned in very direct terms that the treatment of utilities would take much longer and cost much more than might have been anticipated. Ausgrid had also cautioned that the timetable for the Early Works contract was unachievable;

- at no point prior to entry into the Project Deed was there any statement by the defendant, through its various planning groups or Risk Register, that the significant risks that it had been highlighting were somehow reduced. For example, there is no statement that those risks which were highlighted as being major, such as the risk of unknown utilities or delay risks associated with the absence of agreements with utility providers, were reduced by December 2014; and

- the defendant was aware that it needed to engage the proponent on terms that work would be done by the D&C contractor in stages, with limited concurrency between the stages. Thus, it needed to both impose a fee zone schedule and impose terms which would deter OpCo from not complying with that fee zone schedule. This was critical to minimising extensive harmful interaction with business owners along the SLR route.

The Project Deed

- The Project Deed is an extensive document comprising 317 pages with thousands of pages of annexures. The “Definitions” section is itself 62 pages.

- The Project Deed did not just cover the design and construction of the SLR. The agreement which ALTRAC and the defendant entered into was to the effect that ALTRAC would be paid a certain sum in respect of its design and completion of the SLR and that, thereafter, it would have a right to operate it for a period of 15 years.

The fee zone strategy

- Consistently with the announcements made by the government and the representations made to business owners during the government’s promotion of the SLR, the defendant developed what I would describe as a fee zone strategy. Whilst there would be some overlap, there were 31 separate fee zones. Through the Project Deed, the defendant established occupation periods for each fee zone. Further, the IDP attached to the Project Deed set out OpCo’s delivery program in each fee zone.

- Integral to the construction of the SLR was that it be completed in stages. The IDP must be viewed as a realistic and reasonable estimate by OpCo as to how the work could be done consistently with the defendant’s fee zone requirements, based on the information available at the time of entry into the Project Deed and assuming that the utilities risk was appropriately reduced through the pre-Project Deed investigation and planning.

- The IDP set out the expected start and finish dates for works within each fee zone.

- The defendant’s fee zone strategy was intended to ensure that the disruption to business owners along the route was kept to a minimum. Ensuring that the work was done in stages and that the D&C contractor was sufficiently deterred and incentivised was integral to minimising the disruption to businesses.

- However, every time a Utility Works Event (UWE) occurred, and OpCo could demonstrate that a delay to the Occupation Cessation Date for a fee zone was caused, then OpCo could make a claim for an extension to the Base Fee Zone Occupation Period.

- Further, as set out in cl 26.1 of the Project Deed, if a Compensation Event (which is defined to include a UWE) caused OpCo to incur loss, OpCo could claim compensation in accordance with cl 26 (Compensation Events).

- The fee zone strategy thus required the D&C contractor to complete its work in any particular fee zone in accordance with the Occupation Schedule or else it would be subject to a financial penalty, except that:

- the D&C contractor could obtain relief from such penalty and indeed claim compensation for certain events, including (and relevantly to this matter) a UWE; and

- the maximum penalty for overstay over the life of the project was $7.5 million.

- The plaintiffs say that such a contractual arrangement was so unreasonable that no authority exercising the powers of the defendant would have entered into the Project Deed on those terms.

- The defendant rejects this. It says that looking at those terms in isolation ignores the importance of the very significant impost on the D&C contractor arising out of moving from one fee zone to another and leaving work incomplete, being the D&C contractor’s own costs.

Lay evidence as to interference with businesses

- As is clear from the lay evidence, there was either actual construction work or the appearance of construction activities outside the lead plaintiffs’ businesses for periods far in excess of what was contemplated.

Ms Hunt’s evidence

- Ms Hunt provided a detailed chronology as to her observations of the SLR construction activities and the ways in which those construction activities affected Hunt Leather’s business in both stores.

- There was no real challenge to Ms Hunt’s evidence in respect of the period up to December 2017. That is because there is no dispute that, at least between the time of commencement of construction and December 2017, Fee Zone 5 was the subject of regular construction activities and remained boarded up during that time. Specifically, there were hoardings on both sides of the road on George Street and, in particular, directly out the front of the Hunt Leather Strand Arcade store.

- It is clear from the daily photographic record that George Street between King and Market Streets was re-opened in December 2017 and the hoardings which had been in place up until that time were removed (albeit the hoardings remained in place at both King and Market streets).

- Ms Hunt emphasised that the problem for her stores was not just that the works were noisy and dusty, but that customers would have found it difficult to walk up George Street and international tourists were deterred from doing so. As she said, the shopping experience was greatly diminished, not only because of the noise and dust, but also the mere presence of the hoardings and barricades along George Street.

Mr Zisti’s evidence

- According to Mr Zisti, he chose Anzac Parade for his restaurant business because it was on a main road and easily accessible to the public. It had large windows out the front which allowed natural light and enabled customers to look into the premises.

- According to Mr Zisti, the primary source of revenue up until the commencement of the SLR construction was in-house dining, rather than takeaway.

- Mr Zisti says that during the period leading up to the SLR construction, his sales were continuing to increase (I will discuss this later in this judgment).

- Mr Zisti says that on 7 May 2016, construction of the SLR began on Anzac Parade. He recalls that barricades were established around the median strip and parking was removed on either side of the road. The parking lane was designated for traffic.

- According to Mr Zisti, in the first few days of construction, his revenue was reduced by 29%.

- Mr Zisti describes the nature of the construction work which he observed outside his restaurant and the impact on his restaurant on a monthly basis from May 2016 to 2019.

- In July 2018, Mr Zisti decided to save on expenses by closing the restaurant for lunch and only operating during the evenings. He said this caused him to lose the revenue generated by university students, who would generally visit during the daytime.

- In July 2018, he closed the restaurant for a few weeks to remodel and fit out the restaurant business to operate as an Italian restaurant, known as Sugo Pasta Bar. That business name was registered on 3 July 2018.

- Mr Zisti operated Sugo Pasta Bar from August 2018 to April 2019.

- Mr Zisti did not renew the lease when it expired in April 2019.

- As Mr Zisti said, and as his records disclose, 2018 was the first time that his restaurant suffered a loss. He had originally operated a successful business which decreased in profitability after the commencement of the SLR construction. He was not required to continue to operate his business at a loss. A year later, he was forced to decide whether to renew the lease for a period of a further five years. He decided not to. The Italian restaurant was not successful.

Expert evidence

- The parties relied on a range of expert evidence, some of which may be critical to the outcome of the case and some of which was barely relevant. That expert evidence included:

- utilities experts – Edward Szmalko on behalf of the plaintiffs and Craig Sampson on behalf of the defendant. The defendant also adduced evidence from Stephen Lewcock, a utilities manager who had been employed on the SLR project;

- planning and programming experts – Mark Griffith on behalf of the plaintiffs and Ian McIntyre on behalf of the defendant;

- procurement expert – Jarred Hardman on behalf of the defendant;

- noise experts – Neil Gross on behalf of the plaintiffs and Renzo Tonin on behalf of the defendant;

- air quality experts – Gary Graham on behalf of the plaintiffs and Aleksander Todoroski on behalf of the defendant;

- traffic experts – Oleg Sannikov on behalf of the plaintiffs and Shaun Smedley on behalf of the defendant;

- retail experts – Chris Abery on behalf of the plaintiffs and Ian Shimmin on behalf of the defendant; and

- quantum experts – Tony Samuel on behalf of the plaintiffs and Ashley McPhee on behalf of the defendant.

Summary of findings on utilities experts

- There is an extensive review of the expert evidence in the judgment. I will refer only to my conclusions in this summary.

- As I have identified in my review of the evidence of the utilities experts, there are a number of problems with Mr Szmalko’s evidence. Specifically, some of the assumptions he made are not borne out by the evidence and some of his conclusions are directly contrary to the evidence. The basis of some of his opinions is not clear. To the extent that he offered opinions on any alternative delivery model or on the basis that the defendant intended to completely transfer the risk to OpCo through the Project Deed, those opinions cannot be accepted.

- Further, I accept the evidence of Mr Lewcock and Mr Sampson on the difficulties that would have arisen if Mr Szmalko’s proposed alternate delivery models had been adopted.

- Having said that, there is some consistency between the utilities experts on a number of issues. The deterrence clause (cl 12.3) in the Project Deed was described as unique. Investigating utilities prior to commencing the Civil Works was important and necessary. The general effect of Mr Szmalko’s Utilities Mitigations Steps was not really in dispute. The fact that the trenching contract was unlikely to have discovered all utilities was not in dispute, as it was merely a survey. The suggestion of 100% quality level A in Fee Zone 5 was apt to mislead.

- It is also clear from the evidence of Mr Lewcock and Mr Sampson that, as I have already accepted with reference to the pre-Project Deed documents, the presence of unknown utilities was a big risk on this project and that the requirements of utility providers were not finalised and remained a risk at the time of entry into the Project Deed.

- Mr Sampson said that the discovery of previously unknown utilities would make a huge difference to the outcome. As I will explain, he was correct.

- To a certain extent, the defendant’s expert evidence on utilities tended to highlight the significance, risk and complexity of the utilities problem. The defendant’s evidence assisted its case in resisting the s 43A unreasonableness point but also highlighted the fact that the defendant was well-aware of the risk of substantial delay in completing the Civil Works at the time it entered into the Project Deed.

Mr Griffith

- The plaintiffs retained Mr Griffith as their programming expert. The defendant retained Mr McIntyre as its programming expert. At times during their evidence, it did seem like this was a construction case between a principal and a contractor, rather than a claim for damages in nuisance.

- Mr Griffith considered that the delay risk associated with unknown utilities should have been known to the defendant. He says that the defendant should have taken further steps to reduce this risk by:

- undertaking more utility surveys covering the rail alignment and adjacent properties with statistical analysis of the differences between the utility plans and survey results; and

- reaching concluded agreements with utility providers that clearly defined treatment plans and agreed expected procedures.

- Mr Griffith opined that the SLR project took longer than it should have, stating that the planned occupation of Fee Zones 5, 6 and 29 was extended due to the defendant’s conduct.

- In his initial view, the increase in occupation was as follows:

- for Fee Zone 5, from 281 to 1105 days (a 393% increase);

- for Fee Zone 6, from 318 to 1116 days (a 351% increase); and

- for Fee Zone 29, from 191 to 1146 days (a 600% increase).

- In my view, the periods of fee zone occupation were not quite as extensive as he suggests but, on any view, they were much longer than planned and exceeded two years.

- Mr Griffith identified the cause of the delays in the occupation of Fee Zones 5, 6 and 29 as being:

- the number of modifications issued by the defendant during the course of the construction work;

- the discovery of many previously unknown utilities, leading to delays in the treatment these utilities; and

- delays in reaching agreement with utility providers in respect of the treatment of the utilities.

Mr McIntyre

- Mr McIntyre prepared two reports dated 11 February 2022 and 17 November 2022. He was initially asked two questions, being:

- what works occurred in Fee Zones 5, 6 and 29 relevant to the complaints made in the Statement of Claim within the proximity of the premises? and

- did he agree or disagree with Mr Griffith’s opinion as to whether the utilities conduct and any failures identified resulted in any of the Fee Zones 5, 6 or 29 being occupied for longer than otherwise expected?

- He adopted a classification system for the construction and related works. He defined Category 2 activities as moderate or heavy construction or related works. He analysed when Category 2 works were being performed in Fee Zones 5, 6 and 29.

- The second question Mr McIntyre was asked to answer was whether the utilities conduct or any failures identified resulted in the occupation of the fee zones for longer than initially planned. Mr McIntyre did not consider that it was possible to answer this question. He did not agree with Mr Griffith’s methodology of comparing what actually happened with what was shown on the program adopted by the D&C contractor at an earlier point in time.

Summary of programming evidence

- I am persuaded by Mr Griffith’s analysis of what happened on this project. I do not accept, as the defendant submits, that no conclusion on the cause of the substantial prolongation of the D&C contractor’s occupation in the fee zones could be made without tracing the impact of every utility across the life of the project. I do not accept the defendant’s submission that no conclusion can be drawn without evidence of the D&C contractor’s resources and how the delays in each fee zone might have been caused by under-resourcing on the part of the D&C contractor.

- In the end, there was little between Mr Griffith and Mr McIntyre in terms of their assessments of the occupation periods. There was also little between them in terms of the number of days that the D&C contractor actually performed work in the fee zones.

- The real difference between Mr Griffith and Mr McIntyre related to whether Mr Griffith could offer an opinion on the cause of the delays based on his methodology and analysis, or whether, as suggested by Mr McIntyre, that methodology did not provide a proper basis for expressing an opinion as to cause.

- Of course, Mr McIntyre did not offer any opinion as to the cause of the prolonged periods of occupation, merely suggesting that Mr Griffith’s approach was flawed. Further, Mr McIntyre did not offer any opinion as to what a reasonable allowance for the performance of the work in the fee zones might have been, assuming that sufficient utility investigations were undertaken and agreements with providers were in place prior to the commencement of work. Rather, he suggested that, because the so-called counterfactual would involve an entirely different delivery model, there could be no reference to the IDP as a base from which to work.

- Whilst the defendant submits that the plaintiffs have not proved the counterfactual, I understand the plaintiffs to be submitting that the counterfactual is the amended IDP. Of course, it would have always been difficult for the defendant to put forward some alternative counterfactual (not that it was required to do so) because it says that the nuisance was inevitable. I do not accept this. Nor do I accept that in a nuisance claim, the plaintiffs must necessarily expose a counterfactual.

- The difference between the parties on these issues is, again, a reflection of their differing approaches to what the plaintiffs must prove to succeed.

Project scope changes

- As set out in paragraphs 12(c) and 12(d) of the Statement of Claim, the plaintiffs allege that during the course of the project, the defendant issued the D&C contractor with approximately 60 directions to change the scope of those works. The plaintiffs allege that a substantial cause of the project scope changes was the failure by the defendant to effectively plan and procure the project between 2011 and 2014.

- In my view, the only complaint of substance is in respect of Modification 25.

Legal issues

- The parties differ markedly in their approach to the law which applies to this case and their differences have some impact on the outcome.

- Nuisance is a tort. The law of torts is concerned with the allocation of losses which arise incidental to the activities of people in modern society. [12]

- There are many cases where precisely the same facts would establish liability both in nuisance and in negligence. [13] It may be that this case could have been framed in both negligence and nuisance, but it is not. It is only brought in nuisance. It is important not to confuse the concepts. Further, it is important to observe that the plaintiffs do not particularise any failure to exercise reasonable care as part of their pleadings. They refer to failures by the defendant but they do not plead the existence of a duty of care, risk of ham or negligence. They refer to the defendant’s failures in the context of delays in the construction activity.

- One of the central areas of dispute in these proceedings is whether, in order to succeed in their cause of action in nuisance, the plaintiffs must establish that the defendant failed to take reasonable care or acted negligently. The defendant says that the plaintiffs must establish that the defendant failed to take reasonable care in order to succeed. The defendant’s position on nuisance is best summarised in its closing submissions, as follows:

“To suggest that the burden of proof shifts to the Defendant is inconsistent with the very premise of the entire issue. In these circumstances, the existence of negligence is fundamental to, or definitional of, the existence of the nuisance. That is to say, it is only the negligent carrying on of the activity that turns it into an “unreasonable user” of land, with the result that there is a legal nuisance. ….It is thus a matter that the plaintiff must prove in order to establish the existence of the tort…”

- On one view of the case law, there may be some difference of opinion about those propositions. Having said that, the High Court of Australia has not yet held that, in order to succeed in nuisance in a case such as this, a claimant must establish that the tortfeasor acted without reasonable care or “negligently”.

- There are three types of interference with land which may constitute a nuisance:

“(a) causing encroachment on the neighbour’s land, short of trespass;

(b) causing physical damage to the neighbour’s land or any building, works or vegetation on it; and

(c) unduly interfering with a neighbour in the comfortable and convenient enjoyment of his or her land.”

- In this case, the Court is concerned with the third kind of interference noted above, although the plaintiffs’ case is put more broadly than that. On their case, the nuisance is said to involve a combination of factors, including the emanation of things from the defendant’s land onto the plaintiffs’ land (such as noise and dust), the erection of hoardings close to the plaintiffs’ premises and the closing of surrounding areas and roads (which reduced the volume of foot and vehicular traffic near the businesses).

- Not every interference with the use or enjoyment of land gives rise to an actionable claim in nuisance. A balance must be struck between the right of the landowner to use its land as it sees fit and the interest of the adjoining landowner to be protected from interference with their rights as a landowner.

- One way in which that balance is struck is to preclude actions arising out of a mere inconvenience, annoyance or temporary disturbance. This is done by limiting actions to interferences which are substantial.

- The need for the interference to be substantial may be particularly significant in this class action because the level of interference with Group Members along the SLR route varied greatly. Indeed, the level of interference varied even between the three businesses run by the lead plaintiffs.

- Another way in which the balance between competing interests is achieved is through the concept of reasonableness. Consistently with some cases, the defendant describes this as the “reasonable user” principle.

- The defendant highlights the reasonable user principle as the touchstone of liability in a nuisance action, suggesting that it requires the plaintiffs to establish that the defendant has “acted with negligence.”

- The plaintiffs submit in rather simple terms that, in circumstances whereby the use of the adjoining land (that is, the roads constituting the SLR route) was for the development and construction of a light rail, then the use of the land by the defendant could not be described as common or ordinary. The plaintiffs submit that they therefore only need to establish that the interference with their land was substantial, and no more.

- On the other hand, the defendant submits that this rather simple analysis must fail, in part because the construction of the SLR would fall within the meaning of ordinary or common use of the land (the land being public roads and the construction being roadworks) and also because that approach ignores the complex balancing of the parties’ interests which must take place, said to be based on the reasonable user principle.