FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 59 Articles, Issue 59: Feb 2013

Professor Ronald Dworkin was one of the most influential legal philosophers of the last century. He challenged both legal positivism and utilitarianism. His contribution as a public intellectual extended beyond the law to controversial political issues and the nature of democracy. In the last decade of his life he published important works that addressed values of liberty and equality and the question ‘What is a Good Life?’1

His theory of law as integrity requires judges to resolve novel legal problems by a process which includes moral reasoning. Judges are not free to simply impose their moral views on the law. The correct interpretation of a statute or a constitution must reconcile existing legal materials: text and precedent. Still, at least in “hard cases”, judges cannot simply follow the law since there is no existing legal answer to the particular problem. A principle must be discerned that fits existing legal materials. Moral reasoning also is involved. Judges draw on common moral understandings. This is unremarkable when there is a moral consensus. It becomes controversial when there is no moral consensus, such as whether abortion is protected by the constitution or whether the state may restrict the institution of marriage to heterosexual couples.

Dworkin placed human dignity at the centre of his moral and political theories. He identified two principles that citizens should share. The first is that every human life is intrinsically and equally valuable. The second is that each person has a personal responsibility for realising his or her own potential. According to Dworkin, an individual must take his or her own life seriously, and accept that it is a matter of importance that their life be “a successful performance rather than a wasted opportunity”2.

By any measure, and even by the standards of his harshest critics, Ronald Dworkin’s life was a successful performance.

Life and career

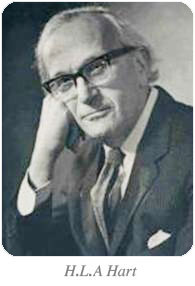

Ronald Myles Dworkin was born in Massachusetts on 11 December 1931. His parents separated when he was young and his mother, a music teacher, supported Dworkin and his two siblings. Dworkin  won a scholarship to Harvard, where he received straight As in all his four years’ classes. Having been awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, he studied law at Oxford, and also apparently played a lot of bridge. His Oxford finals papers were as brilliant as his Harvard results. His undergraduate examiners passed a copy of his jurisprudence paper to the Professor of Jurisprudence, H.L.A Hart. Dworkin’s paper challenged Hart’s arguments, and, according to Hart’s biographer, Hart was amazed by this student’s power of argument. Hart did not take it personally. He would later recommend that Dworkin succeed him to the Oxford Chair of Jurisprudence, and he retained Dworkin’s paper, and quoted from it at Dworkin’s inaugural dinner as an Oxford Professor in 1969.

won a scholarship to Harvard, where he received straight As in all his four years’ classes. Having been awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, he studied law at Oxford, and also apparently played a lot of bridge. His Oxford finals papers were as brilliant as his Harvard results. His undergraduate examiners passed a copy of his jurisprudence paper to the Professor of Jurisprudence, H.L.A Hart. Dworkin’s paper challenged Hart’s arguments, and, according to Hart’s biographer, Hart was amazed by this student’s power of argument. Hart did not take it personally. He would later recommend that Dworkin succeed him to the Oxford Chair of Jurisprudence, and he retained Dworkin’s paper, and quoted from it at Dworkin’s inaugural dinner as an Oxford Professor in 1969.

After graduating in law from Oxford, Ronald Dworkin returned to Harvard to take a further degree in law, and in 1957 worked as a law clerk for Judge Learned Hand, then in his late eighties. Hand has been described as the best judge to have never served on the US Supreme Court. Hand asked Dworkin to read lectures he had drafted for delivery at Harvard in which Hand questioned whether the US Supreme Court had correctly decided Brown v Board of Education, Topeka Kansas. In that 1954 decision the Court had ruled that racially segregated education was necessarily unconstitutional. Dworkin challenged Hand’s views. This was a brave move, since Hand was renowned for his explosive temper. However, Dworkin survived and prospered.

While he was working for Hand Dworkin met his future wife, Betsy Ross. On one of their first dates Dworkin explained that he had to drop a document at the judge’s house and asked her to come in, saying that it would take only a second. Hand invited the couple inside and talked to them for two hours. As they left Hand’s house, Betsy asked Ronald “If I see more of you, do I get to see more of him?”

Often Hand’s clerks went on to work for Justice Felix Frankfurter of the US Supreme Court, ensuring their professional success. Hand wrote a letter of commendation, describing Dworkin as “the law clerk to beat all law clerks”. However, rather than work for Frankfurter (a choice Dworkin came to regret) he joined a Wall Street firm, where he worked between 1958-1962.

Often Hand’s clerks went on to work for Justice Felix Frankfurter of the US Supreme Court, ensuring their professional success. Hand wrote a letter of commendation, describing Dworkin as “the law clerk to beat all law clerks”. However, rather than work for Frankfurter (a choice Dworkin came to regret) he joined a Wall Street firm, where he worked between 1958-1962.

In 1962, Dworkin joined Yale Law School as an academic. In 1969, at the age of 37 he was appointed Professor of Jurisprudence at Oxford; one of the youngest appointments to a chair ever made. In 1975, Dworkin accepted a joint appointment at New York University. After retiring from Oxford, Dworkin became the Quain Professor of Jurisprudence at University College London, where he subsequently became the Bentham Professor of Jurisprudence.

Ronald Dworkin died 14 February 2013 in London at the age of 81. Dworkin’s first wife, Betsy Ross, died in 2000. He is survived by his wife, Irene Brendel Dworkin; his twin children Anthony and Jennifer and his two grandchildren.

Legal Positivism and Taking Rights Seriously

Legal Positivism and Taking Rights Seriously

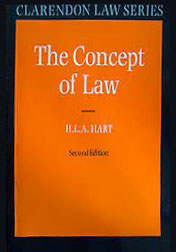

Dworkin’s early work challenged legal positivism, the dominant legal philosophy articulated in Hart’s 1961 book The Concept of Law, which separated moral judgment from legal judgment. Dworkin rejected the view that legal arguments need not involve moral argument. According to Dworkin, there were right answers in hard cases. This contrasted with Hart’s view that in hard cases judges had discretion to make new law.

Dworkin’s interpretative theory is that the law is whatever follows from a correct interpretation of legal materials, aided by moral judgments about what would make the law the best that it could be, and that there is one right answer. This does not mean that most judges will reach the right answer. Judge Hercules, an ideal judge with ample time to study the law and wisely construct a principle to fit the facts of the case, always would come to the right answer. Ordinary judges do not have such luxuries or talents. But, according to Dworkin, there is a right answer, based upon a process of interpretation, even in hard cases.

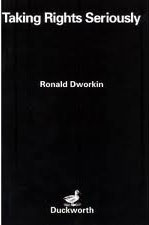

Legal positivism asserts that individuals have only those rights accorded to them by law, political decisions or long-established practices. Law is a matter that has been posited by order, decision or practice, and a law’s validity depends on its sources, not on moral principles. In Taking Rights Seriously Dworkin challenged this prevailing view. He contended that individuals have legal rights beyond those explicitly stated in such sources, and they have political and moral rights against the state that trump the interests of the majority.

Legal positivism asserts that individuals have only those rights accorded to them by law, political decisions or long-established practices. Law is a matter that has been posited by order, decision or practice, and a law’s validity depends on its sources, not on moral principles. In Taking Rights Seriously Dworkin challenged this prevailing view. He contended that individuals have legal rights beyond those explicitly stated in such sources, and they have political and moral rights against the state that trump the interests of the majority.

Fundamental is the right of each individual to the equal respect and concern of those who govern. Individual liberties are not derived from some general right to liberty, but from the right to equal concern and respect itself. Dworkin disputed that liberty and equality were conflicting values.

Interpretation

Interpretation

In Law’s Empire Dworkin further developed the principles upon which the legal system is grounded. Judges decide hard cases by interpreting rather than simply applying past legal decisions. In constitutional cases a court must interpret terms like “equal protection”, “cruel and unusual punishment” and “the right to bear arms” and the task of interpretation involves a moral element. Controversial constitutional cases were not simply disputes about the correct interpretation of text or analysis of precedent. They were struggles about the morality embedded in the constitution.

Two Dimensions of Human Dignity

Ea rly in his writings Dworkin identified equal concern and respect as a fundamental value. He later described it as the sovereign virtue. During the tumultuous and politically divisive first decade of this century, he identified two very basic principles that most of us share, in spite of our great differences on particular issues. It is worth quoting a substantial passage from Is Democracy Possible Here? Principles for a New Political Debate:

rly in his writings Dworkin identified equal concern and respect as a fundamental value. He later described it as the sovereign virtue. During the tumultuous and politically divisive first decade of this century, he identified two very basic principles that most of us share, in spite of our great differences on particular issues. It is worth quoting a substantial passage from Is Democracy Possible Here? Principles for a New Political Debate:

The first principle which I shall call the principle of intrinsic value holds that each human life has a special kind of objective value. It has value as potentiality; once a human life has begun, it matters how it goes. It is good when that life succeeds and its potential is realized and bad when it fails and its potential is wasted. This is a matter of objective, not merely subjective value; I mean that a human life’s success or failure is not only important to the person whose life it is or only important if and because that is what he wants. The success or failure of any human life is important in itself, something we all have reason to want or to deplore. We treat many other values as objective in that way. For example, we think we should all regret an injustice, wherever it occurs, as something bad in itself. So, according to the first principle, we should all regret a wasted life as something bad in itself, whether the life in question is our own or someone else’s.

The second principle the principle of personal responsibility holds that each person has a special responsibility for realizing the success of his own life, a responsibility that includes exercising his judgment about what kind of life would be successful for him. He must not accept that anyone else has the right to dictate those personal values to him or impose them on him without his endorsement. He may defer to the judgments codified in a particular religious tradition or to those of religious leaders or texts or, indeed, of secular moral or ethical instructors. But that deference must be his own decision; it must reflect his own deeper judgment about how to acquit his sovereign responsibility for his own life.

These two principles that every human life is of intrinsic potential value and that everyone has a responsibility for realizing that value in his own life together define the basis and conditions of human dignity, and I shall therefore refer to them as principles or dimensions of dignity. The principles are individualistic in this formal sense: they attach value to and impose responsibility on individual people one by one. But they are not necessarily individualistic in any other sense. They do not suppose, just as abstract principles, that the success of a single person’s life can be achieved or even conceived independently of the success of some community or tradition to which he belongs or that he exercises his responsibility to identify value for himself only if he rejects the values of his community or tradition. The two principles would not be eligible as common ground that all Americans share if they were individualistic in that different and more substantive sense.

These dimensions of dignity will strike you as reflecting two political values that have been important in Western political theory. The first principle seems an abstract invocation of the ideal of equality, and the second of liberty. I mention this now because it is often said, particularly by political philosophers, that equality and liberty are competing values that cannot always be satisfied simultaneously, so that a political community must choose which to sacrifice to the other and when. If that were true, then our two principles might also be expected to conflict with one another. I do not accept this supposed conflict between equality and liberty; I think instead that political communities must find an understanding of each of these virtues that shows them as compatible, indeed that shows each as an aspect of the other. That is my ambition for the two principles of human dignity as well3.

Justice for Hedgehogs

The title of Dworkin’s last book was drawn from the aphorism that “the fox knows many things, the hedgehog one big thing”. It canvasses issues of law and morality, as well as conceptions of living well and the good life. ‘What is a Good Life?’ is the title to an accessible article in the New York Review of Books 4.

Justice for Hedgehogs more fully explores the theme of “authenticity”: giving our lives a meaning which we choose for them and its implications for how we and the state treat others.

Dworkin’s writings engage notions of rights and responsibilities in a way that sits easily with social democratic theory. If an individual is entitled to insist on being treated with dignity then he or she has a duty to make something of themselves, and we must extend the same dignity to others with whom we deal. The responsibility to treat others with dignity has consequences for resource allocation and politics. For example, without a certain standard of public education and public health care, individuals are deprived of the opportunity to make something of themselves.

Theory of equality

Dworkin contributed to debates about what equality means. His theories were founded on the principle that each individual is entitled to equal concern and respect, but this did not dictate equality of outcome. Individuals were responsible for the life choices they made. But endowments of intelligence and talent should not affect the distribution of resources in society. This form of “luck egalitarianism” distinguishes between outcomes that are the result of luck and those that are the consequence of conscious choices. Justice demands that variations in how well off individuals are should relate to the responsible choices they make and not to differences in the circumstances of their birth.

Individual rights and democratic theory

In Taking Rights Seriously, Dworkin stated:

The institution of rights is therefore crucial, because it represents the majority’s promise to the minorities that their dignity and equality will be respected5.

Dworkin’s conception of rights highlights two competing theories of democracy:

The two views of democracy that are in contest are these. According to the majoritarian view, democracy is government by majority will, that is, in accordance with the will of the greatest number of people, expressed in elections with universal or near universal suffrage. There is no guarantee that a majority will decide fairly; its decisions may be unfair to minorities whose interests the majority systematically ignores. If so, then the democracy is unjust but no less democratic for that reason. According to the rival partnership view of democracy, however, democracy means that the people govern themselves each as a full partner in a collective political enterprise so that a majority’s decisions are democratic only when certain further conditions are met that protect the status and interests of each citizen as a full partner in that enterprise. On the partnership view, a community that steadily ignores the interests of some minority or other group is just for that reason not democratic even though it elects officials by impeccably majoritarian means6.

Critics

As a proud liberal Democrat, Ronald Dworkin engaged in debates, both in public and in print. He was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books.

As a proud liberal Democrat, Ronald Dworkin engaged in debates, both in public and in print. He was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books.

The right wing jurist, Robert H Bork, who once jointly taught a law class with Dworkin at Yale, and whose nomination for the US Supreme Court was blocked, described Dworkin’s approach as a smokescreen. In 1997 Bork wrote:

Dworkin writes with great complexity but, in the end, always discovers that the moral philosophy appropriate to the Constitution produces the results that a moral relativist prefers.

Judge Richard A Posner in 2001 launched a similar attack on Dworkin’s writings as partisan and predictable:

Dworkin’s dominant bent as a public intellectual is to polemicize in favour of a standard menu of left-liberal policies.

The trouble with these ad hominem attacks is they challenge the left/liberal result of Dworkin’s arguments, not the arguments themselves. But it is possible to challenge his arguments, and their consequences. In a recent piece, Professor Eric Posner of the University of Chicago (not to be mistaken with Judge Richard A Posner), accepted that Dworkin’s sophisticated theory of interpretation provides:

an accurate and defensible description of how judges develop the common law … and interpret statutes. Although judges deny that they “make law,” Dworkin rightly pointed out that when confronted with legal texts like statutes, judges must draw on general background norms to interpret them, and these norms frequently reflect common moral and political suppositions. Where there is a moral consensus, the use of these norms is almost invisible. And when judges disagree, or make mistakes, legislatures can easily correct their decisions by passing new statutes7.

But, according to Eric Posner, Dworkin made a “wrong move” in applying his ideas to disputes over the meaning of the US Constitution.

Constitutional law differs from statutes and the common law in two relevant ways. First, the process to amend the Constitution is extremely cumbersome, so that if the Supreme Court declares that pornography or campaign spending is protected by the right to free speech, it is virtually impossible for the public to undo this ruling by electing legislators who oppose pornography or support campaign finance reform. Second, the Constitution and most of its significant amendments were produced a century or two ago, when the country was radically different. As a result, they provide only limited guidance today and hence maximum space for judges to “interpret”.

Moreover, Supreme Court justices face no negative consequences if they interpret the Constitution so as to advance their ideological commitments. … Because our system gives judges so much power, Supreme Court justices are able to impose their ideological commitments over an enormous range of public policy issuesâhealth care and gun control, criminal punishment and sexual freedom, religious liberty and public schooling8.

Others argue that Dworkin’s theory of constitutional interpretation gave an excessively large role to federal judges in American society. One such critic is Professor Jeremy Waldron, who questions the democratic legitimacy of judicial review. Waldron and Dworkin also differed over the desirability of  hate-speech laws, with Dworkin opposing such laws on free speech grounds9.

hate-speech laws, with Dworkin opposing such laws on free speech grounds9.

Waldron, a former student of Dworkin, describes being inspired, challenged and even annoyed by Dworkin’s work. Waldron accurately describes Dworkin as “a giant in legal and political philosophy”. As to their disagreements, Waldron recalls:

I always learned a lot from these disagreements. When I was a graduate student at Oxford, I would bring him papers on rights and property and equality, and I would sit in his room at University College, listening to him take my ideas apart. It wasn’t really disagreement at that stage, it was learningâlearning what it was like to argue seriously, learning what it meant to be responded to as someone worth arguing with. Everything I have written bears the improving mark of those rigorous sessions10.

Other former students describe his generosity in reading their undergraduate papers and framing their arguments in their best possible form before dismantling them. As Waldron observes:

I learned to appreciate and reciprocate the cheerfulness and good humor of my supervisor. I learned how to write gracefully under pressure. I came to understand that it was a privilege to have my papers taken apart and taken seriously11.

A similar theme appears in the recollections of Harvard Professor, Charles Fried:

Anyone who has undergone the discipline of the famous NYU seminars he conducted with his friend and infinitely subtle, refined intellectual peer, Thomas Nagel, would see the life of reason in its highest form. An invitee would offer a paper, which all the participants would have read beforehand. Dworkin and Nagel would take him to lunch and the three of you would decide what are the main themes and pressing questions raised by the paper. Then that afternoon at the seminar itself the two of them would present the guest’s thesis to the assemblage. I am sure I am not the only such guest who found that their presentation of his thesis was finer and richer than he himself might have thought. For it was their, and certainly Ronnie’s fundamental style to look for what was the very best in any argument, and only then to proceed to criticize and perhaps to dismantle or demolish it12.

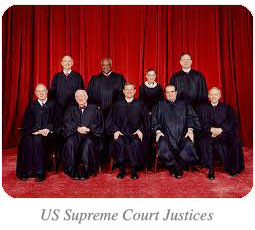

Citizens United v FEC and the Roberts Court

Dworkin had an elegant writing style. His arguments were beautifully constructed and delivered with verve. He took exception to the 2010 decision of the US Supreme Court in Citizens United v FEC. His compelling critique of the decision appeared in an article titled ‘The Decision that Threatens Democracy’13. It starts:

No Supreme Court decision in decades has generated such open hostilities among the three branches of our government as has the Court’s 5—4 decision in Citizens United v FEC in January 2010. The five conservative justices, on their own initiative, at the request of no party to the suit, declared that corporations and unions have a constitutional right to spend as much as they wish on television election commercials specifically supporting or targeting particular candidates 14.

No Supreme Court decision in decades has generated such open hostilities among the three branches of our government as has the Court’s 5—4 decision in Citizens United v FEC in January 2010. The five conservative justices, on their own initiative, at the request of no party to the suit, declared that corporations and unions have a constitutional right to spend as much as they wish on television election commercials specifically supporting or targeting particular candidates 14.

Dworkin then proceeds to expose flaws in the majority’s decision, its inconsistency with free speech principles and precedent and its terrible implications. He pulls no punches in his conclusion:

The Supreme Court’s conservative phalanx has demonstrated once again its power and will to reverse America’s drive to greater equality and more genuine democracy. It threatens a step-by-step return to a constitutional stone age of right-wing ideology. Once again it offers justifications that are untenable in both constitutional theory and legal precedent. Stevens’s remarkable dissent in this case shows how much we will lose when he soon retires. We must hope that Obama nominates a progressive replacement who not only is young enough to endure the bad days ahead but has enough intellectual firepower to help construct a rival and more attractive vision of what our Constitution really means15.

The Supreme Court’s conservative phalanx has demonstrated once again its power and will to reverse America’s drive to greater equality and more genuine democracy. It threatens a step-by-step return to a constitutional stone age of right-wing ideology. Once again it offers justifications that are untenable in both constitutional theory and legal precedent. Stevens’s remarkable dissent in this case shows how much we will lose when he soon retires. We must hope that Obama nominates a progressive replacement who not only is young enough to endure the bad days ahead but has enough intellectual firepower to help construct a rival and more attractive vision of what our Constitution really means15.

Last year, he wrote an article ‘The Court’s Embarrassingly Bad Decisions’ which shows that his analytic powers and writing style remained to near the end of his life. He elaborated on the theme that many of the most important constitutional clauses are drafted in abstract language; and justices must interpret those clauses by trying to find principles of political morality that explain and justify the text and the past history of its application. He wrote:

They will inevitably disagree about which principles best satisfy that test, and they will inevitably be influenced, in making that judgment, by their own sense of what a good constitution would provide.

But that does not mean that the justices are free to interpret the abstract clauses of the Constitution to match their own political convictions, whatever these are. It is essential to the rule of law that they accept the constraints as well as the responsibilities of the jurisprudence of principle. They must rely only on principles that they honestly think provide a persuasive justification for our actual constitutional traditions. They must set out the principles on which they rely in their opinions transparently; and they must apply those principles consistently across all the cases that come before them. They must not invent arbitrary exceptions when these principles yield results they find uncongenial. Unless justices accept those constraints, they are only unelected politicians16.

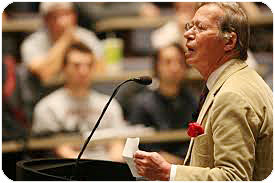

Lectures and public debates

Ronald Dworkin was a master rhetorician. He defended his liberal democratic views and his legal philosophy in public debates, sometimes with acerbic lines. An observer recalls him devastate Judge  Richard Posner at a conference at the University of Chicago, at which Posner promoted his theory of wealth maximisation, which Dworkin systematically dismembered.

Richard Posner at a conference at the University of Chicago, at which Posner promoted his theory of wealth maximisation, which Dworkin systematically dismembered.

I had the privilege to attend some of his seminars at Oxford in 1984 at which he would deliver a brilliant series of arguments over a two hour period, occasionally glancing at a few notes written on a piece of paper the size of a small envelope.

A Professor Nagel recalls Dworkin giving a “beautifully constructed 50-minute lecture” at Stanford after being introduced by the University’s President. After it was over the President rose and explained that he had inadvertently picked up the Professor’s detailed notes from the lectern after introducing him. This did not stop Dworkin from launching into the lecture without his notes17.

The person

Such a gracious act, in launching into a lecture without notes rather than embarrass the University President, is consistent with reports of Dworkin’s personal qualities. The Felix Frankfurter Professor of Public Law at Harvard University, Carl Sunstein, recounts his own disagreements with Dworkin in person and in print:

But I learned , as did everyone who encountered him, that he had one of the finest and most probing minds on the planet, and that if you were lucky enough to lose an argument to him (winning was out of the question), your own understanding would be immeasurably improved. He was not only a giant but also a good and gracious man18.

He divided his time almost equally between the United States and Britain, with houses in Lond on, New York and Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, where he sailed. A recent obituary observed:

on, New York and Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, where he sailed. A recent obituary observed:

For a man who contrived, through sheer intellectual brilliance and a formidable capacity for work, to be both a consummate scholar’s scholar and a lawyer’s lawyer, Dworkin could give the impression of something not far from indolence. He loved company, talk, good food and drink, music, including opera, and travel, and moved easily through the different societies of New York and Martha’s Vineyard, Oxford and London. Friends and family were more important to him than society, however, and work perhaps ultimately, in spite of his apparently self-indulgent lifestyle, more important than either19.

Product value or performance?

In ‘What makes a Good Life?’ Dworkin observes that we may count a life’s positive impact as the way the world is itself better because that life was lived — as its product value. Instead, he argued, as did ancient philosophers, that a good life is a harmonious life achieved through order and balance which may have no impact at all. Lives spent in the satisfaction of conviviality, friendship and family have subjective value, and it is “the performance rather than the product value of living that way that counts”.

In sheer product value, Ronald Dworkin left the world with the output of a remarkable mind and an individual of exceptional industry. By all reports, his life was a successful performance, and, by his own definition, therefore a good life.

The Epilogue to Justice for Hedgehogs discusses two ethical ideals: living well and having a good life. In it Dworkin reflects on how individuals who suffer bad luck, great poverty or serious injustice can live well without having a good life. Many people lead contented lives without wealth. Also, the unjustly rich may have a life that lacks value, living in a nation split between affluence and desperate poverty. He observes that it “counts against the value of a life that it is led with other people’s money, and nothing they can do with their additional wealth can make up that value shortfall”20. And he remarks that cultures have tried to teach:

a malign and apparently persuasive lie: that the most important metric of a good life is wealth and the luxury and power it brings. … The ridiculous dream of a princely life is kept alive by ethical sleepwalkers. And they in turn keep injustice alive because their self-contempt breeds a politics of contempt for others21.

According to Dworkin, these people use their wealth politically to persuade the public to elect or accept leaders who will make them even richer. The injustice of a nation split between great affluence and desperate poverty means that the poor suffer more because they are aware of their misfortune. But Dworkin argues that the rich suffer as well since “it makes it difficult for most of them to lead as good a life as they could in less unjust circumstances”22.

The Epilogue ends with this distillation:

The justice we have imagined begins in what seems an unchallengeable proposition: that government must treat those under its dominion with equal concern and respect. That justice does not threaten Â- it expands – our liberty. It does not trade freedom for equality or the other way around. It does not cripple enterprise for the sake of cheats. It favors neither big nor small government but only just government. It is drawn from dignity and aims at dignity. It makes it easier and more likely for each of us to live a good life well. Remember, too, that the stakes are more than mortal. Without dignity our lives are only blinks of duration. But if we manage to lead a good life well, we create something more. We write a subscript to our mortality. We make our lives tiny diamonds in the cosmic sands23.

Conclusion

Ronald Dworkin was more than a legal philosopher. His decades as a public intellectual and champion of liberal causes rank him as a great political philosopher. He developed a sophisticated theory of democracy, eschewing crude majoritarian conceptions of democracy, and developing a philosophy that sought to integrate moral and political theory. Contrary to received wisdom, liberty and equality are not in conflict. Properly understood, these values could be seen as reflective of a fundamental principle that requires human dignity to be respected.

Ronald Dworkin was more than a legal philosopher. His decades as a public intellectual and champion of liberal causes rank him as a great political philosopher. He developed a sophisticated theory of democracy, eschewing crude majoritarian conceptions of democracy, and developing a philosophy that sought to integrate moral and political theory. Contrary to received wisdom, liberty and equality are not in conflict. Properly understood, these values could be seen as reflective of a fundamental principle that requires human dignity to be respected.

His harshest critics accused him of being chief ideologist of a “rights culture” and spawning a human rights industry. Those critics may not have appreciated the sophistication of his arguments, and his clear and early concession that most areas of the law must reflect the will and interests of the majority. They also ignore the fact that Dworkin’s focus was not simply on rights against the state. His concern extended to the responsibility of each individual to fulfil their potential and to live authentically.

His contribution to debates on numerous controversial issues ranging from abortion to election campaign finance should not overshadow his achievement in the area of legal philosophy, in which he departed from two prevailing legal philosophies. The first was legal positivism, with its conception of law as what the established conventions of society say it is. The second was law as an instrument by which judges and others seek to improve society. Dworkin rejected both views. He argued that judges are engaged in interpreting past legal materials and, at least in hard cases, are writing a new chapter of the law based upon an interpretation of what has gone before. The judge could not properly write a new chapter that did not fit with a principle that emerged from the existing legal materials. But the process of making new law was not a mechanical exercise, free from individual and collective morality. A judge did not have a discretion to make new law in a novel case. There was a right answer, not easily found, but one dictated by a process of interpretation.

Dworkin should be remembered for his big idea, which put human dignity at the centre of political philosophy and democratic practice.

If, instead, he is simply to be remembered for his defence of rights, one might choose to read the concluding paragraphs of his essay Taking Rights Seriously, which first appeared in the December 17 1970 edition of the New York Review of Books. The Vice President at the time the essay was written was one Spiro Agnew, who argued that “the liberals’ concern for rights was a headwind blowing in the face of the ship of state”. Incidentally, Agnew was to resign later in disgrace. Yet similar views about liberals’ concern for rights can be found most days in the pages of our national newspapers. Ronald Dworkin’s response is both prescient and compelling:

The Vice President supposes that rights are divisive, and that national unity and a new respect for law may be developed by taking them more skeptically. But he is wrong. Our country will continue to be divided by its social and foreign policy, and if the economy grows weaker the divisions will become more bitter. If we want our laws and our legal institutions to provide the ground rules within which these issues will be contested, then these ground rules must not be the conqueror’s law that the dominant class imposes on the weaker, as Marx supposed the law of a capitalist society must be. The bulk of the lawâthat part which defines and implements social, economic, and foreign policyâcannot be neutral. It must state, in its greatest part, the majority’s view of the common good. The institution of rights is therefore crucial, because it represents the majority’s promise to the minorities that their dignity and equality will be respected. When the divisions among the groups are most violent, then this gesture, if law is to work, must be most sincere.

The institution requires an act of faith on the part of the minorities, because the scope of their rights will be controversial whenever they are important, and because the officers of the majority will act on their own notions of what these rights really are. Of course these officials will disagree with many of the claims that a minority makes. That makes it all the more important that they take their decisions gravely. They must show that they understand what rights are, and they must not cheat on the full implications of the doctrine. The government will not re-establish respect for law without giving the law some claim to respect. It cannot do that if it neglects the one feature that distinguishes law from ordered brutality. If the government does not take rights seriously, then it does not take law seriously either24.

Justice Peter Applegarth

Supreme Court of Queensland

February 2013

Introduction photo: Professor Dworkin in High Street, Oxford

Footnotes

1. Ronald Dworkin, ‘What is the Good Life?’ (2011) 58(2) New York Review of Books.

2. Ronald Dworkin, Justice for Hedgehogs (Harvard University Press, 2011) 203.

3. Ronald Dworkin, Is Democracy Possible Here? Principles for a New Political Debate (Princeton University Press, 2006) 9-11.

4. Ronald Dworkin, ‘What is the Good Life?’ (2011) 58(2) New York Review of Books. Available at http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/feb/10/what-good-life/?pagination=false .

5. Ronald Dworkin, ‘Taking Rights Seriously’ (1970) 15(11) New York Review of Books.

6. Ronald Dworkin, Is Democracy Possible Here? Principles for a New Political Debate (Princeton University Press, 2006) 131.

7. Eric Posner, ‘Ronald Dworkin’s Error’ Slate Magazine 19 February 2009 <http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/view_from_chicago/2013/02/ronald_dworkin_the_legal_scholar_s_big_mistake.html>.

8. Ibid.

9. For videos of their speeches: http://abcdemocracy.net/2012/07/06/ronald-dworkin-and-jeremy-waldron-on-hate-speech/ .

For Justice John Paul Stevens 2012 review of Waldron’s book see: “Should Hate Speech be Outlawed?” http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/jun/07/should-hate-speech-be-outlawed/?pagination=false .

10. Jeremy Waldron, ‘Remembering Ronald Dworkin’ The Chronicle of Higher Education 19 February 2013 http://chronicle.com/blogs/conversation/2013/02/19/remembering-ronald-dworkin/>.

11. Ibid.

12. Charles Fried, ‘Remembering Ronald Dworkin’ New Republic 18 February 2013

<http://www.newrepublic.com/article/112451/ronald-dworkin-memoriam >.

13. Ronald Dworkin, ‘The Decision that Threatens Democracy’ (2010) 57(8) New York Review of Books.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ronald Dworkin, ‘The Court’s Embarrassingly Bad Decisions’ (2011) 58(9) New York Review of Books. Other recent essays can be found at http://www.nybooks.com/contributors/ronald-dworkin-2/.

17. Adam Liptak, ‘Ronald Dworkin, Scholar of the Law, is Dead at 81’ New York Times (New York) 14 February 2013.

18. Carl Sunstein ‘The Most Important Legal Philosopher of Our Time’ Bloomberg, 16 February 2013

<http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-15/the-most-important-legal-philosopher-of-our-time.html >.

19. Godfrey Hodgson, ‘Ronald Dworkin Obituary’ The Guardian (London) 14 February 2013.

20. Ronald Dworkin, Justice for Hedgehogs (Harvard University Press, 2011) 422.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.423.

24. Ronald Dworkin, ‘Taking Rights Seriously’ (1970) 15(11) New York Review of Books.

won a scholarship to Harvard, where he received straight As in all his four years’ classes. Having been awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, he studied law at Oxford, and also apparently played a lot of bridge. His Oxford finals papers were as brilliant as his Harvard results. His undergraduate examiners passed a copy of his jurisprudence paper to the Professor of Jurisprudence, H.L.A Hart. Dworkin’s paper challenged Hart’s arguments, and, according to Hart’s biographer, Hart was amazed by this student’s power of argument. Hart did not take it personally. He would later recommend that Dworkin succeed him to the Oxford Chair of Jurisprudence, and he retained Dworkin’s paper, and quoted from it at Dworkin’s inaugural dinner as an Oxford Professor in 1969.

won a scholarship to Harvard, where he received straight As in all his four years’ classes. Having been awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, he studied law at Oxford, and also apparently played a lot of bridge. His Oxford finals papers were as brilliant as his Harvard results. His undergraduate examiners passed a copy of his jurisprudence paper to the Professor of Jurisprudence, H.L.A Hart. Dworkin’s paper challenged Hart’s arguments, and, according to Hart’s biographer, Hart was amazed by this student’s power of argument. Hart did not take it personally. He would later recommend that Dworkin succeed him to the Oxford Chair of Jurisprudence, and he retained Dworkin’s paper, and quoted from it at Dworkin’s inaugural dinner as an Oxford Professor in 1969. Often Hand’s clerks went on to work for Justice Felix Frankfurter of the US Supreme Court, ensuring their professional success. Hand wrote a letter of commendation, describing Dworkin as “the law clerk to beat all law clerks”. However, rather than work for Frankfurter (a choice Dworkin came to regret) he joined a Wall Street firm, where he worked between 1958-1962.

Often Hand’s clerks went on to work for Justice Felix Frankfurter of the US Supreme Court, ensuring their professional success. Hand wrote a letter of commendation, describing Dworkin as “the law clerk to beat all law clerks”. However, rather than work for Frankfurter (a choice Dworkin came to regret) he joined a Wall Street firm, where he worked between 1958-1962. Legal Positivism and Taking Rights Seriously

Legal Positivism and Taking Rights Seriously Legal positivism asserts that individuals have only those rights accorded to them by law, political decisions or long-established practices. Law is a matter that has been posited by order, decision or practice, and a law’s validity depends on its sources, not on moral principles. In Taking Rights Seriously Dworkin challenged this prevailing view. He contended that individuals have legal rights beyond those explicitly stated in such sources, and they have political and moral rights against the state that trump the interests of the majority.

Legal positivism asserts that individuals have only those rights accorded to them by law, political decisions or long-established practices. Law is a matter that has been posited by order, decision or practice, and a law’s validity depends on its sources, not on moral principles. In Taking Rights Seriously Dworkin challenged this prevailing view. He contended that individuals have legal rights beyond those explicitly stated in such sources, and they have political and moral rights against the state that trump the interests of the majority. Interpretation

Interpretation  rly in his writings Dworkin identified equal concern and respect as a fundamental value. He later described it as the sovereign virtue. During the tumultuous and politically divisive first decade of this century, he identified two very basic principles that most of us share, in spite of our great differences on particular issues. It is worth quoting a substantial passage from Is Democracy Possible Here? Principles for a New Political Debate:

rly in his writings Dworkin identified equal concern and respect as a fundamental value. He later described it as the sovereign virtue. During the tumultuous and politically divisive first decade of this century, he identified two very basic principles that most of us share, in spite of our great differences on particular issues. It is worth quoting a substantial passage from Is Democracy Possible Here? Principles for a New Political Debate:

As a proud liberal Democrat, Ronald Dworkin engaged in debates, both in public and in print. He was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books.

As a proud liberal Democrat, Ronald Dworkin engaged in debates, both in public and in print. He was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books. hate-speech laws, with Dworkin opposing such laws on free speech grounds

hate-speech laws, with Dworkin opposing such laws on free speech grounds No Supreme Court decision in decades has generated such open hostilities among the three branches of our government as has the Court’s 5—4 decision in Citizens United v FEC in January 2010. The five conservative justices, on their own initiative, at the request of no party to the suit, declared that corporations and unions have a constitutional right to spend as much as they wish on television election commercials specifically supporting or targeting particular candidates

No Supreme Court decision in decades has generated such open hostilities among the three branches of our government as has the Court’s 5—4 decision in Citizens United v FEC in January 2010. The five conservative justices, on their own initiative, at the request of no party to the suit, declared that corporations and unions have a constitutional right to spend as much as they wish on television election commercials specifically supporting or targeting particular candidates The Supreme Court’s conservative phalanx has demonstrated once again its power and will to reverse America’s drive to greater equality and more genuine democracy. It threatens a step-by-step return to a constitutional stone age of right-wing ideology. Once again it offers justifications that are untenable in both constitutional theory and legal precedent. Stevens’s remarkable dissent in this case shows how much we will lose when he soon retires. We must hope that Obama nominates a progressive replacement who not only is young enough to endure the bad days ahead but has enough intellectual firepower to help construct a rival and more attractive vision of what our Constitution really means

The Supreme Court’s conservative phalanx has demonstrated once again its power and will to reverse America’s drive to greater equality and more genuine democracy. It threatens a step-by-step return to a constitutional stone age of right-wing ideology. Once again it offers justifications that are untenable in both constitutional theory and legal precedent. Stevens’s remarkable dissent in this case shows how much we will lose when he soon retires. We must hope that Obama nominates a progressive replacement who not only is young enough to endure the bad days ahead but has enough intellectual firepower to help construct a rival and more attractive vision of what our Constitution really means Richard Posner at a conference at the University of Chicago, at which Posner promoted his theory of wealth maximisation, which Dworkin systematically dismembered.

Richard Posner at a conference at the University of Chicago, at which Posner promoted his theory of wealth maximisation, which Dworkin systematically dismembered. on, New York and Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, where he sailed. A recent obituary observed:

on, New York and Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, where he sailed. A recent obituary observed: Ronald Dworkin was more than a legal philosopher. His decades as a public intellectual and champion of liberal causes rank him as a great political philosopher. He developed a sophisticated theory of democracy, eschewing crude majoritarian conceptions of democracy, and developing a philosophy that sought to integrate moral and political theory. Contrary to received wisdom, liberty and equality are not in conflict. Properly understood, these values could be seen as reflective of a fundamental principle that requires human dignity to be respected.

Ronald Dworkin was more than a legal philosopher. His decades as a public intellectual and champion of liberal causes rank him as a great political philosopher. He developed a sophisticated theory of democracy, eschewing crude majoritarian conceptions of democracy, and developing a philosophy that sought to integrate moral and political theory. Contrary to received wisdom, liberty and equality are not in conflict. Properly understood, these values could be seen as reflective of a fundamental principle that requires human dignity to be respected.