FEATURE ARTICLE -

Articles, Issue 100: June 2025

Semipalatinsk is a large area in the north east of Kazakhstan which, in 1949, was known as the Kazakh SSR, one of the constituent republics of the USSR. On 29 August of that year it was where the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic device[i]. The reaction here and elsewhere was one of surprise and of heightened concern about the USSR’s military capacity and intention. General apprehension about the Cold War and the presence of communist spies increased when, a month later, Mao Zedong proclaimed the creation of the Peoples Republic of China.

Against this backdrop of international tension and the dawn of the nuclear age Australia was grappling with its own internal challenges. Shortly before those two events, Australia had been in the grip of one of its most serious strikes. The coal mines were closed and a Labor government had stepped in and used the army to clear strikers. It was a time when, not only Australia, but also many other western nations perceived a direct and substantial threat from communists and their sympathisers.

For contemporary readers, these events may seem distant. That era was defined by leaders such as Clement Attlee, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom; Harry Truman, the President of the United States; and Robert Menzies, who assumed office as Australia’s Prime Minister for the second time in December 1949. Though these events occurred 70-75 years ago, they offer valuable historical lessons about the balance between security and civil liberties.

Marx House, the headquarters of the Australian Communist Party Central Committee on George Street, Sydney, circa 1950. (Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

When Mr Menzies came into office, one of his new government’s highest priorities was the destruction of Australian communism. This was to be achieved through the Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950. The Act outlawed and dissolved the Communist Party of Australia and provided for the confiscation of its assets. Organisations affiliated with or controlled by the CPA could be declared unlawful, and individuals who were or had after 10 May 1948 been members of the CPA could be declared to be so and thus debarred from employment in the Commonwealth Public Service or from holding office in a trade union. A person who was the subject of such a declaration had the onus of proving that he or she was not liable to the making of that declaration.

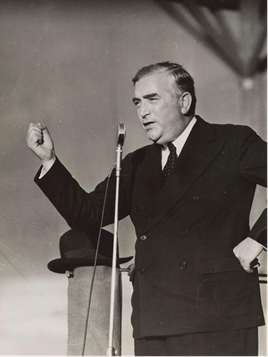

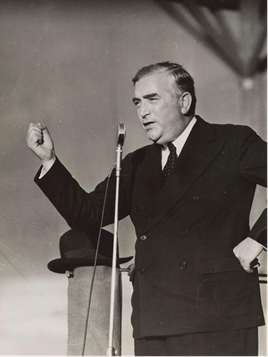

Mr Menzies

This was part of the “war on communism”. It was a conflict about which the participants felt so strongly that they were prepared to cut away at longstanding provisions essential to the healthy survival of the rule of law. Of course we now understand that the Communist Party of Australia, while aligned with the Soviet Union, posed a threat that was not as overwhelming as many then believed. However, it is crucial to understand the prevailing climate of fear and suspicion that shaped the political landscape at the time. That is the precious gift of hindsight. This process was well captured in the words of William Brennan, former Justice of the United States Supreme Court, who said in 1987:

“There is considerably less to be proud about, and a good deal to be embarrassed about, when one reflects on the shabby treatment civil liberties have received in the United States during times of war and perceived threats to national security… After each perceived security crisis ended, the United States has remorsefully realised that the abrogation of civil liberties was unnecessary. But it has proven unable to prevent itself from repeating the error when the next crisis came along.”[ii]

That statement can be neatly contrasted with what was said by Mr Menzies in the House of Representatives after the High Court had ruled that his government’s Communist Party Dissolution Act was unconstitutional. He told the House:

“We cannot deal with such a conspiracy urgently and effectively if we are first bound to establish by strict technical means what an association or an individual is actually doing. Wars against enemies … cannot be waged by a series of normal judicial processes.”[iii]

The decision of the High Court[iv] invalidating the Communist Party Dissolution Act has been described as “undoubtedly one of the High Court’s most important decisions”[v]. Had the Act been upheld and then enforced without scrupulous oversight, then its effect on the rule of law could have been devastating. Former member of the High Court, Michael Kirby, has suggested that apartheid South Africa provided a model of what Australia might have become had the legislation been upheld.[vi]

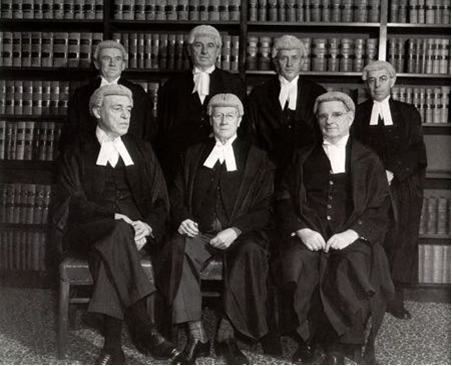

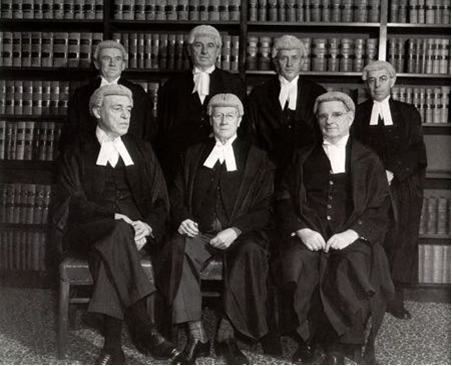

The High Court of AustraliaBack Row: Fullagar, Webb, Williams, and Kitto JJFront Row: Dixon J, Latham CJ, McTiernan J

The ultimate foundation for the decision was the rule of law. It was an example of the constitutional principle that a parliament cannot recite itself into power and, at a more particular level, that only the judicial power is permitted to bridge the gap between making a classification and placing a person within it.[vii]

The Court did not establish a blanket prohibition against reversing the burden of proof, as courts still retain authority to determine whether constitutional facts exist in such cases. Furthermore, the Court acknowledged that while the Commonwealth could not enact such legislation, State governments probably could.

So, who were the principal counsel in the Communist Party case?

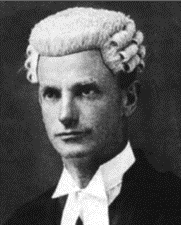

Frederick (Fred) Paterson, a Rhodes Scholar, was counsel for the Communist Party. He was the only representative of the Australian Communist Party to be elected to an Australian parliament. He was the member for the State seat of Bowen from 1944-1950.

Garfield Barwick KC, was leading counsel for the Commonwealth, who later became the Commonwealth Attorney-General, Minister for External Affairs and Australia’s longest serving Chief Justice, led three silks and six juniors at the hearing.

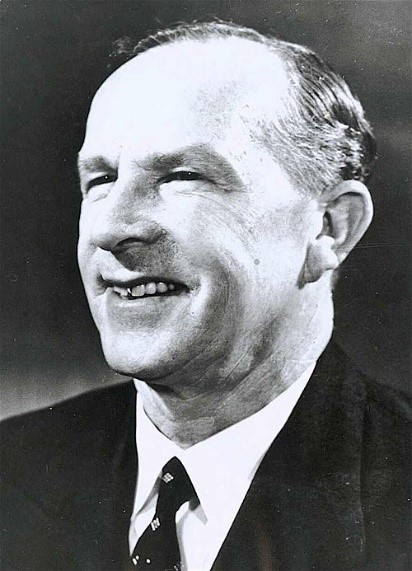

H V (Bert) Evatt KC was counsel for the Waterside Workers Federation and would become the Leader of the Opposition in the Commonwealth Parliament three months after the High Court delivered its decision.

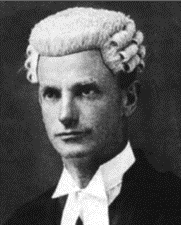

F W Paterson, Counsel for the Communist Party

G E Barwick KC, Leading counsel for the Commonwealth

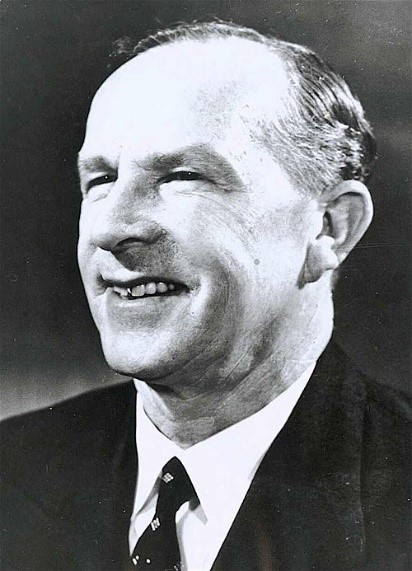

H V Evatt KC, for the Waterside Workers Federation

This case illustrates the proposition that in a settled western democracy, the role of the advocate in the protection and maintenance of the rule of law is essential. While the courts, and depending upon their public persona, some judges, can fleetingly become the objects of veneration for their role in upholding that principle, none of this could occur without advocates willing to develop a case and present it to the court. As Sir Gerard Brennan observed:[viii]

“… the courts are the long-stop. The law which rules is the law according to the rulings of the courts, but it is applied in the offices and chambers of the legal profession. It is applied in drafting and advising; in consultations more than in litigation. But, because the courts are the long-stop and because the rulings of the courts determine the way in which the law operates, judicial decision-making is critical to the maintenance of the rule of law. So it is in litigation that the practising legal profession works at the cutting edge of the rule of law.”

In a settled democracy, where the practice of law can result in a comfortable living, it is sometimes too easy to become more concerned about the prompt payment of fees than the integrity of the institution which allows the fee to be charged. While the courts do resolve the issues and while members of the judiciary do decide the cases which allow the rule of law to be maintained, they do not reach out into the community to bring the cases before them. Without the profession acting for those whose rights have been affected and without its members recognising that sometimes there are aspects of legislation which are inconsistent with the rule of law, then damage can be done.

It is obvious that our society is subject to numerous threats: by terrorists, by organised crime and by the galaxies of unlawful activities which revolve around the sale and consumption of illicit drugs. Evolving criminal methodologies and terrorist tactics demand innovative approaches and a resolute determination to deal with them.

It remains a necessary part of an advocate’s role when engaged in litigation to identify elements of legislation that, despite worthy intentions, may diminish the rule of law. This obligation can be complex. Whether in jurisdictions with human rights legislation or without, advocates serve the rule of law by applying validly enacted laws and interpreting them appropriately. The common law has always sought a balance between individual freedoms and community protections. If legislatures restrict fundamental freedoms or diminish common law values, advocates must be prepared to present arguments challenging these actions.

As Sir Gerard Brennan concluded:

“Sometimes that may be an anxious duty, sometimes difficult to perform. But that has long been the experience of a robust and proud profession.”[ix]

[i] In 2007, the capital of this area, Semipalatinsk City, changed its name to Semey because its existing name had negative associations due to the extensive atomic testing which had taken place.

[ii] ‘The quest to develop a jurisprudence of civil liberties in times of security crises’ (1988) 18(11) Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 1.

[iii] 212 Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 13 March 1951, 366.

[iv] Australian Communist Party v The Commonwealth (1951) 83 CLR 1 (Dixon, McTiernan, Williams, Webb, Fullagar and Kitto JJ agreeing; Latham CJ in dissent).

[v] George Winterton, ‘The Significance of the Communist Party Case’(1992) 18 Melbourne University Law Review 630.

[vi] ‘H V Evatt, The Anti Communist Referendum and Liberty in Australia’ (1991) 7 Australian Bar Review 93, 100-101.

[vii] Geoffrey Sawer, ‘Defence Power of the Commonwealth in Time of Peace’ (1953) 6 Res Judicatae 214, 219.

[viii] ‘The Role of the Legal Profession in the Rule of Law’ in Francis Neate (ed), Rule of Law: Perspectives from Around the Globe (LexisNexis, 2009).

[ix] Ibid.

Marx House, the headquarters of the Australian Communist Party Central Committee on George Street, Sydney, circa 1950. (Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Marx House, the headquarters of the Australian Communist Party Central Committee on George Street, Sydney, circa 1950. (Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Mr Menzies

Mr Menzies

The High Court of AustraliaBack Row: Fullagar, Webb, Williams, and Kitto JJFront Row: Dixon J, Latham CJ, McTiernan J

The High Court of AustraliaBack Row: Fullagar, Webb, Williams, and Kitto JJFront Row: Dixon J, Latham CJ, McTiernan J

F W Paterson, Counsel for the Communist Party

F W Paterson, Counsel for the Communist Party

G E Barwick KC, Leading counsel for the Commonwealth

G E Barwick KC, Leading counsel for the Commonwealth

H V Evatt KC, for the Waterside Workers Federation

H V Evatt KC, for the Waterside Workers Federation