â A Perspective from the Bar

For practising barristers, the courthouses of Queensland are not regarded as mere workplaces or offices of government. They have a special character â both practical and symbolic â as the places which have been historically set apart for the delivery of justice according to law.

The public proceedings in court buildings are usually adversarial and stressful â for the complainants who have been injured or wronged, for the defendants who face prison or ruin, for the witnesses whose memories and honesty are being publicly tested, for the lawyers whose efforts may affect the fate of their clients and for the judges and jury members who must decide the fate of others.

These proceedings are conducted in a principled and ritualised way â before a Judge who has sworn an oath to do equal justice to all persons, through lawyers who have sworn oaths of honesty and fidelity, and through the testimony of witnesses who have sworn oaths of truthfulness.

To serve their purpose, court buildings should provide a practical environment in which proceedings of this nature can be safely and efficiently conducted. Ideally, their architecture should also convey â to those directly involved in court proceedings and to society as a whole â the independence and authority of the courts and their historic commitment to resolving disputes on a fair and principled basis.

There are about 1000 practising barristers in Queensland, each with their own views as to which of the State’s courthouses best achieve these objectives.

Their preferences are often quite personal. So the purpose of this essay is not to suggest that the Queensland Bar has any single, unified view about the merits of the former Law Courts complex in Brisbane or the new Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law. It is simply to record some of the views which have been widely expressed within the Bar, at the present point of transition from the old to the new.

The Bar’s perspective of the courthouses is largely from the viewpoint of a regular visitor, rather than as a permanent resident. For this reason, perhaps, it is difficult to recall any concern being expressed about the lack of natural light in the courtrooms of the former Law Courts complex. Indeed, this feature had its advantages. On most levels of that building, the layout allowed visitors to assemble outside the courtrooms in an attractive gallery area overlooking a shaded garden courtyard, which created the centrepiece of the complex. The natural light, the garden outlook and the extensive use of carpet and fabric all had a calming effect. When visitors were required in court, however, there was a marked transition, as they passed through heavy doors into a formal, internal courtroom, which was designed to focus attention on the bench and the witness box. For lawyers and laypeople alike, the change in atmosphere was a very clear signal of the solemnity and importance of the proceedings within the courtroom. Given the natural limits of sustained concentration, these proceedings were usually only conducted in one to two hour sessions. So it was never long before visitors could return again to the outside world â with the reverse transition to a more natural and serene environment.

This effect was magnified in the Banco Court of former Law Courts complex. This courtroom was constructed on a grand scale, with gently raking public seating which could accommodate more than 300 visitors. The walls were lined with numerous full-length formal portraits of the State’s Chief Justices, creating a suitably impressive atmosphere for the Court’s ceremonial occasions and for the hearing of appeals and other significant court proceedings.

Rather than being concerned about the lack of natural light within these courtrooms, the Bar was more concerned about their functional and technological limitations and their somewhat worn and dated appearance. Given the magnitude of the changes in technology and trial processes which had occurred in the 30 years since 1981, there was a clear need to develop a new courthouse which could accommodate these changes and provide the additional court facilities required to meet the needs of the State’s expanding population.

Rather than being concerned about the lack of natural light within these courtrooms, the Bar was more concerned about their functional and technological limitations and their somewhat worn and dated appearance. Given the magnitude of the changes in technology and trial processes which had occurred in the 30 years since 1981, there was a clear need to develop a new courthouse which could accommodate these changes and provide the additional court facilities required to meet the needs of the State’s expanding population.

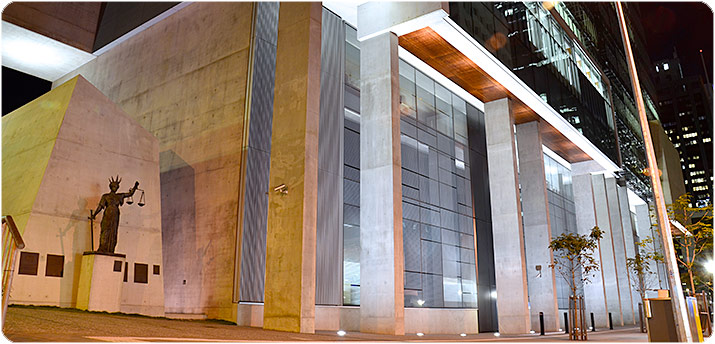

The opening of the new Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law gave much to admire. It is a striking building, and its setting on a public square, does convey something of the independence and authority of the courts. The logic and functionality of the building, with its separate circulation systems for judges, juries and persons in custody, are impressive. The spacious foyers, the modern courtrooms and the attractive judges’ chambers are a tribute to all involved in the planning and design process.

However, the new building has not been without its share of controversy. Amongst members of the Bar, there seemed to be seven main topics of debate.

First, there is the choice of finishes. Many welcomed the fresh and modern approach. For some, however, the extensive use of exposed concrete and plywood created an unduly harsh environment, which lacked some of the warmth which had been achieved in the former Law Courts by the use of carpets, fabrics and colour. If it was hoped that the environment would help visitors deal with the stress of the occasion, then for some at least this may not have been achieved.

Secondly, there are the acoustics. In busy courts, such as the applications court, the timber flooring seems to magnify the sound of footsteps and the murmur of private conversations. To some extent, this problem affects all the courtrooms, as members of the public and visiting students regularly come and go. Fortunately, the courtrooms have a sophisticated electronic sound system, which goes a long way towards alleviating this problem. In the views of some, however, the distraction of noise can only be resolved by the installation of carpet on the courtroom floors â a solution which would seem to be equally controversial.

Thirdly, there is the lighting. In general, the introduction of natural light through the wall of glass behind the bench has been well received. There are, however, two unfortunate side effects. From a barrister’s perspective, the source of the natural light can introduce more than the usual element of glare from the bench (sometimes compounded by reflections from other buildings). Conversely, when the level of natural light is low, it can also be a little difficult to read papers from a lectern (as the task lights are built into the bar table at a lower level). These problems are being overcome, to some extent, by the simple measure of lowering blinds (when necessary) and introducing clip-on lights to the lecterns.

Fourthly, there is the Banco Court. For some, the first sight of the new ceremonial court was rather shocking. The height and proportions of the courtroom were impressive, but in functional terms it seemed too small to accommodate the number of visitors who conventionally attend ceremonial occasions. The eastern wall of glass overlooking the square was certainly striking, but the treatment of the southern wall above the bench was puzzling. Why was this massive mural thought relevant or appropriate for the State’s principal courtroom? Why was it painted around a single massive, off-centre concrete buttress? And what was the buttress doing there anyway? Time has softened most of these initial reactions â particularly with the installation of the judicial portraits from the former Banco Court in the gallery area immediately outside the new court. Indeed, the Banco Court and the gallery area have quickly become a popular focus of public events at the court.

Fifthly, there is the design of the Library. In theory, the Library seemed to have all the facilities which could be desired â extensive shelving space, ample work areas, a large lecture room and numerous private conference and study rooms. In reality, for many users, the Library simply does not provide a work space which is either welcoming or efficient. Efforts to develop suitable workspaces, and reconfigure at least part of the Library’s collection, are continuing.

Sixthly, there is the matter of symbolism. It is easy to be dismissive of the familiar symbols which appear in courthouses throughout the western world â the scales of justice, the figure of Themis, the legal maxims, the neo-classical elements, the coats of arms, the sculptures and judicial portraits. These familiar symbols are, however, highly effective in marking a building as being dedicated to the delivery of justice according to law. If they are not to be used, is there nothing to take their place? For some, it is a matter for regret that the external form of the new building contains little to distinguish it as a courthouse, that the new public artwork appears to serve only an aesthetic role and that the familiar statue of Themis has been relegated to a position of no importance.

Finally, there is the name of the building. In a modern constitutional monarchy, there was always a case for naming a court complex in honour of a well-loved sovereign. For many, however, this was an unusual choice in modern Australia.

Controversies of the nature were inevitable in a project of this significance and complexity, and they need to be kept in their proper perspective. The new court complex is a significant improvement upon its predecessor in almost all respects and, for many, a remarkably effective building.

Mr John McKenna QC*

* Chair, History and Publications Committee, Supreme Court Library Queensland. This article was originally published in the Queensland Legal Yearbook 2012 published by the Supreme Court of Queensland Library and appears by courtesy of the Library

Rather than being concerned about the lack of natural light within these courtrooms, the Bar was more concerned about their functional and technological limitations and their somewhat worn and dated appearance. Given the magnitude of the changes in technology and trial processes which had occurred in the 30 years since 1981, there was a clear need to develop a new courthouse which could accommodate these changes and provide the additional court facilities required to meet the needs of the State’s expanding population.

Rather than being concerned about the lack of natural light within these courtrooms, the Bar was more concerned about their functional and technological limitations and their somewhat worn and dated appearance. Given the magnitude of the changes in technology and trial processes which had occurred in the 30 years since 1981, there was a clear need to develop a new courthouse which could accommodate these changes and provide the additional court facilities required to meet the needs of the State’s expanding population.