Good civic architecture is always expressive of the values of the institution that it houses, and of the relationship of that institution with the democratic society it serves. As such, law courts should express the contemporary values of justice and the law, and the inter-relationship of these with democratic society as a whole.

It follows that the appearance of the new Courts Complex should, from outside and within, convey a real sense of the transparency of justice and be seen to be both reassuring and inviting to all participants without appearing to be intimidating or elitist.

Such sentiments no doubt influenced the Chief Justice’s vision for the project — requiring a design to be developed that would not present as a “fortress, the very antitheses of 21st century accessible Justice”.

That then was the design challenge set for the architectural team — Architectus Brisbane and Guymer Bailey.

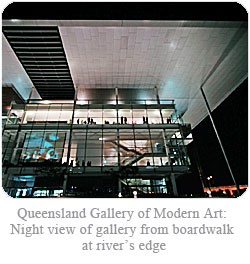

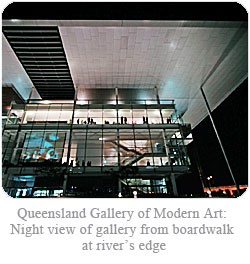

Senior architects in Architectus have provided design services on many signature projects, including the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Chifley Tower, the Neville Bonner Building, and the University of the Sunshine Coast. They also designed the Commonwealth Law Courts building which was completed in 1993 and is recognised as one of the best working courts in Australia. It was delivered 100 days ahead of schedule and within its $130 million budget. The design has attracted numerous awards including the FDG Stanley Award from the RAIA for Design Excellence and the BOMA Award for Best Building.

Senior architects in Architectus have provided design services on many signature projects, including the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Chifley Tower, the Neville Bonner Building, and the University of the Sunshine Coast. They also designed the Commonwealth Law Courts building which was completed in 1993 and is recognised as one of the best working courts in Australia. It was delivered 100 days ahead of schedule and within its $130 million budget. The design has attracted numerous awards including the FDG Stanley Award from the RAIA for Design Excellence and the BOMA Award for Best Building.

Guymer Bailey Architects have similarly won numerous design awards for their work, including the prestigious Royal Australian Institute of Architecture’s commercial architecture award. Their principals, Tim Guymer and Ralph Bailey, have together and individually lectured and published numerous papers and articles on architectural design, vernacular architecture, sustainable architecture, use of timber, furniture design, graphics, ecodesign, ecotourism, landscape planning and design.

Guymer Bailey Architects have similarly won numerous design awards for their work, including the prestigious Royal Australian Institute of Architecture’s commercial architecture award. Their principals, Tim Guymer and Ralph Bailey, have together and individually lectured and published numerous papers and articles on architectural design, vernacular architecture, sustainable architecture, use of timber, furniture design, graphics, ecodesign, ecotourism, landscape planning and design.

Professor John Hockings of Architectus was designated to head up the design team. Professor Hockings is a designer of some renown, an academic, researcher and architectural critic. Before joining Architectus, he was Head of the School of Design at QUT and, prior to that, Head of the Department of Architecture at the University of Queensland. His specialisations are in the fields of architectural design, urban design, subtropical design, and vernacular architecture, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. He has been the recipient of a number of architectural awards and prizes including first prize in the Sydney 2000 Olympic Village International Design Competition. His recent architectural research and practice has been focused on appropriate and sustainable design for tropical and subtropical regions. In 2003, he co-founded and was inaugural Director of the Centre of Subtropical Design.

Given the design brief — to create an architecture which reflects the values of an open, transparent and accessible justice system, and which possesses a dignity and a sense of permanence which reflects the seriousness of the institution being housed — the design team settled upon the following guiding principles:

Given the design brief — to create an architecture which reflects the values of an open, transparent and accessible justice system, and which possesses a dignity and a sense of permanence which reflects the seriousness of the institution being housed — the design team settled upon the following guiding principles:

- To design an architecture in which the public spaces and courts are generous in scale, calm in character, filled with abundant natural light and connected visually with the outside world;

- To achieve a layout in which all spaces and the movements between them are simple and immediately legible;

- To shape a series of spaces and the relationships between them which are dignified and reflect and enhance the seriousness of the social/legal transactions;

- To design a building which is sustainable and enduring in all its aspects.

So far as the environs were concerned, the team’s “urban idea” or site concept involved:

- The creation of a major new public civic square for the city which will also act as a forecourt to the Supreme and District Courts;

- The reinforcement and extension of the Tank Street axis as a major new entry axis to the CBD and, in this regard, the Architectus designed Gallery of Modern Art also acknowledges the city grid and axis of Tank Street, whilst maintaining the river connection for the west end district and, as such, would perfectly complement the new Courts Complex;

- The completion of the legal precinct as an integrated urban component which “bookends” the George Street civic axis, with Parliament House at the eastern end, the Executive Building in the centre and the Supreme and District Courts at the western end;

- The creation of the desirable people connections between Tank Street, the Transit Centre, Roma Street Gardens, and the major public buildings in the immediate precinct;

- The extension of Roma Street as a boulevard;

- The extension of George Street as a boulevard.

Also of consideration was that the architecture should unmistakably echo the sentiments of equality, and should, in combination with the civic square, be clearly readable as a place that belongs to the people, the city and the State.

Also of consideration was that the architecture should unmistakably echo the sentiments of equality, and should, in combination with the civic square, be clearly readable as a place that belongs to the people, the city and the State.

As the idea of transparency evolved, the design team was also very aware of the potentially contradictory requirements brought about by the need for security and privacy which has traditionally led to the ‘fortress’ approach to courthouse design. However, one of the basic tenets of subtropical architecture offered a way to resolve this dilemma.

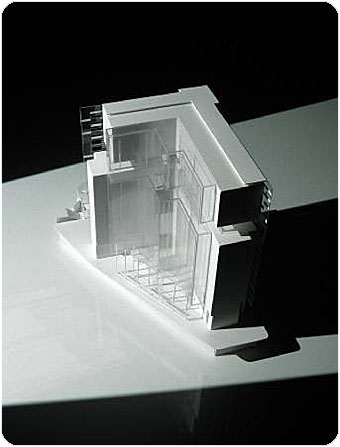

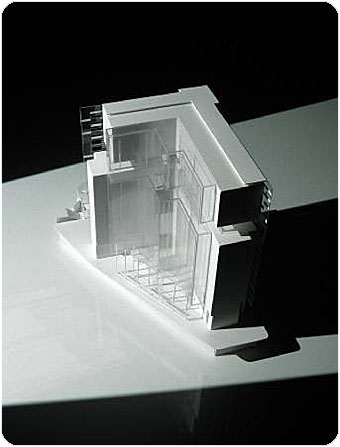

A significant characteristic of subtropical architecture which seeks to link with its surrounding environment and yet control the manner and extent of that linkage has been to develop an architectural skin or shell to the building which is layered, adaptable, and flexible. The shell or skin filters light, view, climate, and privacy.

Through sensitive adaptation, such a design can at the one time screen from external and undesirable circumstances, admit favorable external circumstances, and still permit good connection from the interior to the exterior. The differing quality of the light between the sheltered inside and the outside provides a natural condition where visibility from the inside to the outside is high and visibility from the outside to the inside is muted and more obscure.

Screens and blinds, and variations of transparency and opacity control view and privacy and security. Gaston Bachelard used the word “diaphanous” to capture this quality: light, delicate and translucent. The design team’s approach was to use these familiar and tested ideas to mediate between the controlled secure environment and the project aspirations for open transparent and connected spaces.

In recognition of these principles, Architectus and Guymer Bailey proposed a building enveloped in a sophisticated arrangement of a double skin of glass and screens which provides:

In recognition of these principles, Architectus and Guymer Bailey proposed a building enveloped in a sophisticated arrangement of a double skin of glass and screens which provides:

- Security;

- Privacy;

- Natural light;

- Views;

- Solar control; and

- Climate control.

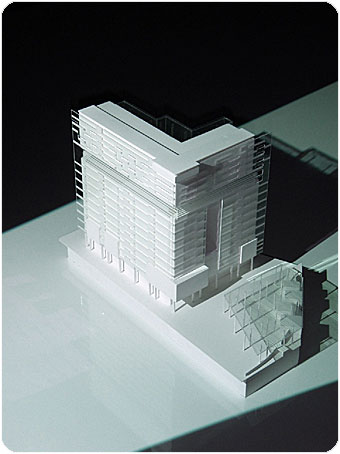

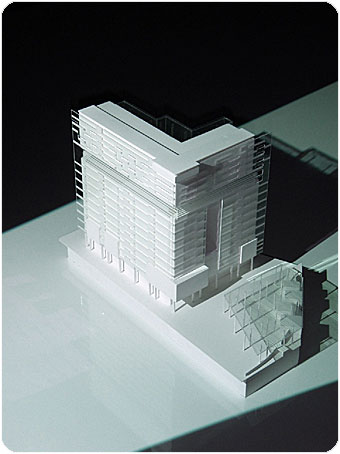

In the resulting design, the Complex when built will be a technologically advanced subtropical courthouse. A delicate arrangement of clear glass, translucent glass, variable blinds, and internal double glazing will wrap the Complex in a truly diaphanous veil which responds ideally to the desire to convey openness and transparency, and yet also gives the most sophisticated control over security and privacy.

In the end, Architectus and Guymer Bailey have created a sophisticated, open, accessible and transparent design in sharp contrast to the existing precast concrete courthouse. The design indeed jettisons the “fortress approach of the old” and introduces an extraordinary degree of transparency, openness and legibility.

Note: The models featured in this article are indicative only, and are subject to change.

Senior architects in Architectus have provided design services on many signature projects, including the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Chifley Tower, the Neville Bonner Building, and the University of the Sunshine Coast. They also designed the Commonwealth Law Courts building which was completed in 1993 and is recognised as one of the best working courts in Australia. It was delivered 100 days ahead of schedule and within its $130 million budget. The design has attracted numerous awards including the FDG Stanley Award from the RAIA for Design Excellence and the BOMA Award for Best Building.

Senior architects in Architectus have provided design services on many signature projects, including the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Chifley Tower, the Neville Bonner Building, and the University of the Sunshine Coast. They also designed the Commonwealth Law Courts building which was completed in 1993 and is recognised as one of the best working courts in Australia. It was delivered 100 days ahead of schedule and within its $130 million budget. The design has attracted numerous awards including the FDG Stanley Award from the RAIA for Design Excellence and the BOMA Award for Best Building. Guymer Bailey Architects have similarly won numerous design awards for their work, including the prestigious Royal Australian Institute of Architecture’s commercial architecture award. Their principals, Tim Guymer and Ralph Bailey, have together and individually lectured and published numerous papers and articles on architectural design, vernacular architecture, sustainable architecture, use of timber, furniture design, graphics, ecodesign, ecotourism, landscape planning and design.

Guymer Bailey Architects have similarly won numerous design awards for their work, including the prestigious Royal Australian Institute of Architecture’s commercial architecture award. Their principals, Tim Guymer and Ralph Bailey, have together and individually lectured and published numerous papers and articles on architectural design, vernacular architecture, sustainable architecture, use of timber, furniture design, graphics, ecodesign, ecotourism, landscape planning and design. Given the design brief — to create an architecture which reflects the values of an open, transparent and accessible justice system, and which possesses a dignity and a sense of permanence which reflects the seriousness of the institution being housed — the design team settled upon the following guiding principles:

Given the design brief — to create an architecture which reflects the values of an open, transparent and accessible justice system, and which possesses a dignity and a sense of permanence which reflects the seriousness of the institution being housed — the design team settled upon the following guiding principles: Also of consideration was that the architecture should unmistakably echo the sentiments of equality, and should, in combination with the civic square, be clearly readable as a place that belongs to the people, the city and the State.

Also of consideration was that the architecture should unmistakably echo the sentiments of equality, and should, in combination with the civic square, be clearly readable as a place that belongs to the people, the city and the State. In recognition of these principles, Architectus and Guymer Bailey proposed a building enveloped in a sophisticated arrangement of a double skin of glass and screens which provides:

In recognition of these principles, Architectus and Guymer Bailey proposed a building enveloped in a sophisticated arrangement of a double skin of glass and screens which provides: