FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 99: March 2025, Reviews and the Arts

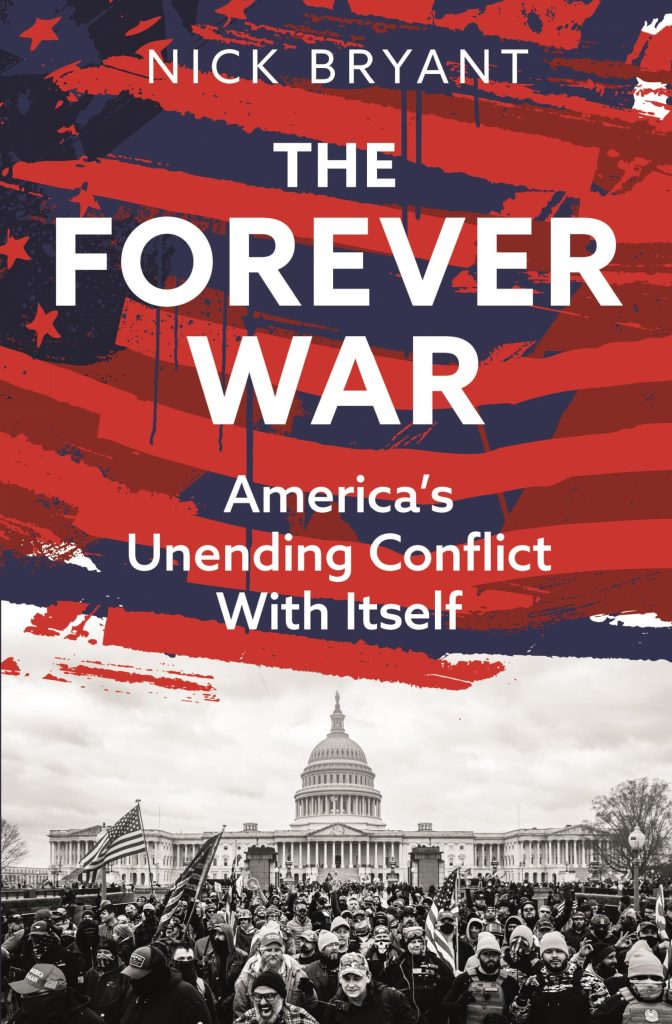

Author: Nick BryantPublisher: Viking (an imprint of Penguin Books)Reviewer: Stephen Keim

The Forever War owes much of its inspiration to the re-emergence of Donald Trump as the Republican nominated candidate for the 2024 election for the Presidency of the United States. Although published in 2024 and, therefore, strikingly contemporary at the time of my reading of the book and the writing of this review, the book went to press before Bryant and the rest of us became aware that Trump had triumphed in the November election and is to become the 47th President of the United States on 20 January 2025.

Nonetheless, The Forever War is not a book about Trump. The Forever War is intended to place the most recent emergence of Trump in an historical context. The Forever War is about the history of the colonial project that became the United States and the history of that country from its emergence from that project until now.

The intention of The Forever War is to cut away the myths which the United States promulgates about itself; its history; its political and social system; and its virtues and to reveal a much starker and bleaker reality. In the context, so provided, Trump appears less of an anomaly and more of a product of the forces at work in American society for more than 200 years.

Bryant comes to American history and politics, uniquely equipped. He was a BBC correspondent for nearly 30 years. He spent some of that time in Australia. (I managed to have a short conversation with him, sometime in 2007.) One of his five books is The Rise and Fall of Australia: How a Great Nation Lost its Way. He spent time covering the United States in the 1990s and, again, for a period that included the Trump years. In addition to these journalistic credentials, Bryant did an undergraduate degree in history at Cambridge and then completed a PhD in American politics from Oxford.

To achieve his purpose, Bryant is remorseless in plumbing past and recent history. Each chapter provides a history of the American Republic focussed on a different aspect of myth destruction. So, chapter 1, The Strange Career of American Democracy, describes in detail how the founding fathers of American democracy were not, in fact, proponents of that philosophy but, rather, regarded such a form of government as dangerous and how their great work, the Constitution of the United States of America, was carefully designed to avoid rule by the people from ever taking place. It goes on to describe the long history of legal stratagems and violence used to prevent persons of colour from voting in elections in the United States including the 1946 fatal shooting of US army veteran, Maceo Snipes, and the almost contemporaneous Moore’s Ford lynchings which resulted in the shooting deaths of two Black married couples who, also, had the temerity to vote. The result of Bryant’s historical analysis is that the modern attempts of Republican politicians to make voting more difficult for minority voters, such as requiring state issued photographic ID to vote in elections, and, thereby, to reduce participation seems more a continuation of an ongoing pattern rather than an unprecedented evil.

Chapter 2, From July 4th to January 6th, looks at the history of politically motivated violence in the United States, much of it largely disappeared from public consciousness, which has punctuated the two and a half centuries since the Declaration of Independence and the Revolutionary War. Until very recently, the destruction of homes and businesses and the massacre of 300 Black residents in “Black Wall Street”, the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 was entirely swept clean from the historical record. As with the history of attempts to restrict the right to vote, the widespread use of violence to gain social and political ends over time places the attack on the Capitol of 6 January 2021 in a perspective which makes it appear to be more part of a continuing pattern than an aberration.

Chapter 3, The Demagogic Style in American Politics, and chapter 4, American Authoritarianism, draw similar lessons as to continuity rather than novelty and, for obvious reasons, have particular applicability to Trump, himself.

Two chapters, chapter 7, In guns we trust, and chapter 8, Roe, Wade and the Supremes, stress discontinuity rather than the sense of a continuing pattern. Between them, they provide a wonderful guide to anyone interested in a short but enlightening history of the Supreme Court of the United States of America.

Chapter 7, which documents the destructive effect on life in America of unrestricted gun laws, also documents a history in which politics transformed the meaning of the Second Amendment from a provision to protect the original states’ ability to maintain civilian militias into a guarantee of entirely unrestricted private gun ownership.

The twenty-seven words of the Amendment appear to make its original intended meaning very clear: “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.” As Bryant documents, that was, for most of the nation’s history, uncontroversial, and sensible gun ownership restriction laws were supported on a bi-partisan basis. As he also documents, myth making by the gun manufacturing industry and political intervention by the National Rifle Association changed all that. Bryant points out that the wildness of the Wild West was vastly overstated, first, by encouraging the publication of dime novels and, latterly, by the production of movie westerns all of which created the impression of a west that was, at best, exaggerated and, in reality, in the most part, fictional.

Chapter 8’s discussion of the Supreme Court highlights that the original intention of the framers of the Constitution for the Court was that it be neither powerful nor important in the exercise of government. While Marbury v Maddison changed the power ratios by creating the principle of judicial review, the membership of the Court was not a subject of significant partisan disputation until the last half century.

Another singular lesson is that, when Roe v Wade was decided, abortion was opposed by the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church but was not a cause celebre for either the Protestant Churches or the right wing of American politics. That has all changed, of course, and the cause of overthrowing Roe v Wade became the cause of stacking the Supreme Court with right wing ideologues. Both objectives have been achieved to the detriment of the American populace which, despite Republican success at all levels of government, still supports ready access to abortion by a healthy majority.

Bryant’s thesis is that America has always been at war with itself. That led to a civil war in the early 1860s which left a peace in which slavery was abolished but the race question was never resolved in a way that established consensus. The antipathy against black Americans and other minorities has continued to be expressed through violence and legal restrictions and created division at all levels of politics. Other issues, the distribution of political power; immigration; sexual identity; and reproduction have all attracted the creation of insoluble division and the resort to violence. America is and has been, forever, in unending conflict with itself.

Bryant’s closing chapters are vaguely but not deeply optimistic. He sees no end to the continuation of deepening partisanship and ongoing loss of respect between those arranged against one another in political struggle. However, he thinks regular resort to a hot war of political violence, in the near term, is unlikely. His epilogue mourns, in gentle tones, his own falling out of love with America.

The Forever War is an extremely readable piece of historical writing in which the reader is provided with a historical context denied them by almost any other medium which deals with contemporary political events. As events unfold from 20 January 2025, it will provide a touchstone to which one can return, again and again.

The Forever War is, nonetheless, a history of the United States from an American point of view. There is some discussion of opposition to America becoming an imperial power at the time that the royal government was overthrown in Hawaii with American government involvement in 1893. In the decade that followed, there was some controversy about the extent to which the United States should go to war with Spain and, in victory, take control of former Spanish possessions. It was, at the same time, that Hawaii was annexed. But The Forever War does not deal in any depth with the impact of America’s repeated interventions overthrowing governments throughout the world including regularly acting to remove democratically elected governments.

This is not surprising. Perhaps, this is because, with rare exceptions when the cost of imperial action has become too much, such as when the Vietnam War dragged on and on, such actions have not created the kind of internal bitterness and division raised by a Black person voting or a woman having an abortion.