FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 69: Sept 2014, Speeches and Legal Articles of Interest

Given in the Banco Court, at the official opening of the Path to Abolition, a History of Execution in Queensland — 18 June 20141

I was very humbled to be invited to speak at this event, because I am not much of a history scholar. Much of what I read in preparation for this evening was new to me.

Before being invited to speak tonight, I did not know that Queensland was the first state in the British Empire to abolish capital punishment – the first state in the Empire to make this humanitarian and socially sophisticated move.

And as a Queenslander that made me proud.

So, expanding on the theme of this exhibition — the path to abolition — I wanted to look into what it was that drove Queensland to take this step — what provided the impetus for this significant change.

I have been helped greatly in preparing for tonight by the library and its excellent researchers — in particular Adam Connolly and Zack George — and by my own excellent researcher Jemima Welsh.

The materials I’ve drawn upon include a published thesis by Ross Barber, from 1967, which was part of his Honours degree in Government, entitled Capital Punishment in Queensland and an article by Mr Anthony Morris QC, from 2002, about the Trial of the Kenniff Brothers; Australia’s last bushrangers.

The other source of my content for this evening has been the newspaper reports from the 18 and 1900s about the trials which led to executions in Queensland and about the executions themselves – which were obtained for me by the library.

I found in those reports opinions about the skill of trial judges, comments and opinions about the skill or otherwise of the executioner and an emphasis on the conversion to Christianity of the condemned at the gallows. I found often a report of an execution accompanied the details of a confession said to have been made by the prisoner to prisoner warders before their death, in what seemed to be an attempt at proving that the execution was justified. And there was often a comment at the end of an article that the process of execution itself was a sad and ghastly affair.

But what struck me most about the articles on executions was how matter-of-factly they were reported and the inclusion in the reports of details of the death and the deceased’s final seconds of life in a way which would be considered, I thought, too macabre for today.

And when I checked that idea by looking at current reports of executions in other parts of the world, I found that it was very rare for the detail of the manner of death to be included.

The change in the content and nature of the reports of executions, for Australian consumption at least, of course reflects the change in the thinking of the community about capital punishment at the different times. Then it was thought to be a distasteful necessity. Now, there is recognition that capital punishment is abhorrent to human dignity and there is no desire or demand for details of the executions.

Coming back to the path to abolition in Queensland and the impetus for change — it will come as no surprise to you that they were many factors at play. And as with almost all social change, it took the abolition movement some time to achieve its goal.

It seems to me that in Queensland, abolition was achieved at a time when there was a coincidence of, or a coexistence, of

- majority, though slim majority, political will in favour of abolition — of course;

- public sentiment in favour of abolition; and

- and enough favourable media.

So we find in the years leading up to abolition —

- Queensland politicians passionate about it & ultimately in a position to do something about it;

- a growing unease or moral discomfort about capital punishment in the community & a desire to become, or to be seen to be, more sophisticated and less barbaric;

- And then one or two hangings which particularly troubled the consciences of many;

It was in that environment that abolition was achieved.

The Act which abolished the death penalty in Queensland, the Criminal Code Amendment Act, received Royal Assent on the 31st of July 1922.

Ted Theodore was the premier at the time, having succeeded TJ Ryan, who’d moved on to Federal politics in 1919. The Labor party had been in power in Queensland since 1915.

A good ‘point’ on the path to abolition to start consideration of the political impetus for change is the mid 1890s — so just before Federation, with Queensland having been a separate colony since 1859.

By the mid-1890s, there had already been a significant winding back of the offences which attracted a death sentence.

By the mid-1890s, the arguments in favour of capital punishment had evolved beyond those which focused on revenge — the life for a life arguments — to those which focused on what was said to be its deterrent effect.

At that time, in all but the most brutal cases, arguments were made, usually successfully, particularly in the cases of white Australians, for commutation of the death sentence to one of imprisonment for life.

In 1899, the Criminal Code Bill was introduced into the Queensland Parliament.

At that time, the majority of the Parliamentary Labor Party was opposed to the abolition of capital punishment, although in the years immediately before its introduction, there had been no executions in Queensland.

The Criminal Code Bill proposed that rape and armed robbery with wounding be removed from the list of capital offences but it retained the death penalty for murder and a couple of other offences like treason.

The public mood at the time was against the execution of persons for murder which was not premeditated. This prompted Sir Samuel Griffith to draw a distinction in the draft code between murder and wilful murder. Wiful murder was a killing with an intention to kill. At its simplest, murder was a killing with an intention to inflict some grievous bodily harm.

Sir Samuel Griffith proposed that in the case of a conviction for a murder other than a willful murder, the sentence of death could be ‘recorded instead of being actually passed’ as was then the case in almost every other capital case.

The distinction between murder and wilful murder was adopted in the Code as passed, and the original section 652 of the Code permitted a sentencing Court, in the case of any capital offence, except treason or wilful murder, to record rather than pass a judgment of death where the Court thought it was proper that the offender be recommended for Royal mercy. That was the means by which the Court could convey its evaluation of the offence to the government.

The first member of the Queensland Parliament to call for more than just a winding back of capital punishment and to call for its total abolition was Joe Lesina, who gave the first speech in response to the Attorney General’s second reading speech relating to the Criminal Code Bill.

He was then a lone voice without support from influential members of the Labor movement. He spoke for two hours against what he called judicial murder.

He began his speech by talking about the gradual reduction in capital offences which had taken place over the century and reforms in European states.

He suggested that there had been an elevation in the moral tone of society — which allowed him to appeal for the abolition of the last vestiges of punishment by mutilation — the lash and the gallows.

And he continued (these are extracts):

I am opposed to these punishments because they are forms of mutilation and are altogether foreign to civilized ideas of punishment.

Our punishment today is largely punitive instead of being reformative. Instead of hanging criminals we should place them in correctional institutions.

The purpose of punishment should be to cure the offender. The criminal is not a wild beast. My view of him is that he is an erring brother whose feet have wandered from the narrow path which we all weakly strive to follow. Undoubtedly he must be punished, but to take his life is not the way to cure him.

Crime is largely a social product – it is the outcome of our present social conditions. It’s greatest breeding grounds are the highly centralised cities of modern industrialized society

Poverty and ignorance are the chief causes of crime.

The alteration of our social and industrial conditions are reforming influences which will have the effect of reducing crime.

I say that murder is just as much murder when authorised and directed by the executive as when it is committed on cold-blood by the private individual.

He also said:

If I should fail it is only I who have failed [for] somebody else as surely as the sun will rise tomorrow will take the matter up where I leave it. I feel perfectly sure that it will not be many years longer before the humanitarian feeling which is now spreading through this colony, and all civilized countries, will demand once and for all the abolition of the death penalty.

We hear in that language appeals to humanitarian ideals and a plea for a civilized approach to punishment in Queensland.

To test Mr Lesina’s statement about the elevation of the moral tone of society, I looked at the newspaper reports from the 1860s onwards. And what I found, generally, supported that observation.

Execution was considered at the least a distasteful practice and there was a certain respect in the reports for those who gave it an aura of respectability — so respect for priests and clergy who saved the soul of the condemned, respect prisoners who were calm and brave, an respect for hangmen who performed the execution ‘well’.

On the whole though the reports of executions were matter-of-fact and only in rare cases given prominence.

In newspapers for colonies outside Queensland, there were usually single columns dealing with the news from other colonies or States — and it was not unusual to find a brief report of an execution in Queensland followed immediately by a report about the Queensland weather and the shipping news.

In Queensland itself, for example, in 1864, a report of the death sentence passed on Alexander Richie was sandwiched between reports about the Warwick races, a police officer being given a gold watch and an evening tea meeting of the ladies of the Wesleyan denomination.

Some reports included what the condemned person had for breakfast on the morning of their execution and almost all commented on their demeanor — whether they were composed or anxious. And as I said, there was respect paid to those who accepted their punishment calmly or who ‘walked firmly’ to the scaffold or who ‘bore themselves well’ and much time spent on the conversion of the condemned and the saving of their soul.

The articles include reports of sentencing judges speaking of their duty in passing the death penalty as a painful one – of it being not their sentence but the sentence required by law – reports about sentencing judges being deeply affected and praying in Court that God would have mercy on the soul of the prisoner.

Side-tracking just a little — there was one particularly commentary which caught my eye. In 1872, the Brisbane Courier said that the judge in the trial of Patrick Collins summed up in a ‘masterful manner’, and after 35 minutes, Collins was convicted of murder. And about that same case, the Queensland Times said that the case had been ‘so wonderfully got up by the Crown’ that anything but a conviction was out of the question.

But mostly, the articles conveyed repugnance. The condemned were referred to as unfortunate or miserable, weak-minded, neglected or misguided.

In 1865, the Courier described the execution of Rudolph Mourberger as a disgusting ceremony and added that it was rendered more so by the cool and off-hand way in which the hangman performed his duty. In 1868, the Courier referred to a hangman making his ghastly preparations. In 1870 the Courier called a hangman disgustingly brusque and officious ‘and rather to relish the work before him’. In the 1870s, the Darling Downs Gazette referred to the morbid taste of the multitude.

So we do find the elevation in moral tone detected by Mr Lesina — though as I said, he was then without much support.

It has been suggested that one reason for the lack of support was that Labor then stood for a White Australia and many members of the Labor movement were then hostile towards ‘coloured aliens’ — in particular, Kanakas (workers imported from the Pacific Islands) and the Chinese because they were an economic threat to white laborers and to unionism.

There was a disproportionately high crime and execution rate among Kanakas and a point to be made about the corrupting influence of Kanakas at each execution.

Even after the passing of Federal legislation which terminated the transportation of Kanakas to Australia there was a tendency to ignore the executions of Kanakas and Chinese.

It was more effective to publicly protest against capital punishment when it was possible to generate public discontent — or to take advantage of existing public discontent — about the person to be executed.

And that can be seen in the case of the Kenniff Brothers — an example which particularly invigorated public opposition to capital punishment.

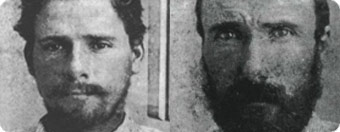

The Kenniff brothers – James and Patrick – were horse stealers from Roma.

In 1902, they were pursued by police and indigenous trackers and James was caught.

He was bound and left with two police officers while the rest of the police and the trackers continued to hunt for Patrick.

They could not find Patrick & when they returned to where James and the two police officers had been left, no one was there — although there were bullet marks in surrounding trees and indications that human remains had been burnt.

After a massive man hunt, James and Patrick were arrested and charged with murder of the two police officers.

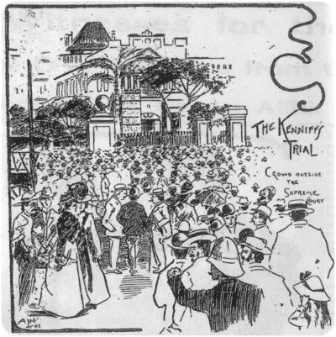

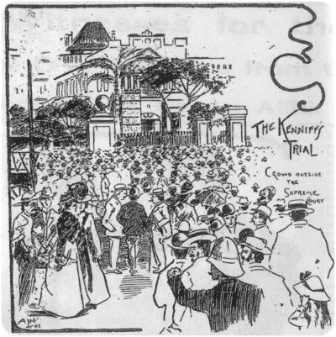

The brothers were not tried in Roma — as would have been usual — instead they were brought to Brisbane.

Their trial was before the Chief Justice, Sir Samuel Griffith — but instead of being tried by a jury of 12, they were tried by a special jury of 4.

From left: Chief Justice Sir Samuel Griffith, Justice Sir Pope Cooper, Justice Patrick Real, Justice Charles Chubb

Legislation existed which permitted the Crown to apply for a special jury rather than a common jury. A special jury was not a jury selected randomly, but rather a jury made up of affluent people like property owners or business men.

The idea behind special juries was that they might be required in cases of particular complexity. One of the complexities relied upon by the Crown in this case was that the evidence against the brothers was circumstantial. But it was of course likely that men of the class included in special juries would have no sympathy for the Kenniffs.

The brothers had no barrister at trial. They were represented a solicitor. They were both convicted — in about an hour — of wilful murder.

At that time, there could be no appeal from that verdict, but instead, questions of law could be reserved to the Full Court.

A report of their trial and the verdicts included this:

When, after an hour, the jury returned

with their verdict, the prisoners were visibly

nervous. The jury announced that they

found both the prisoners guilty.

Patrick Kenniff was asked had he anything

to say before sentence was passed. ‘Yes,’

he said, in a husky voice, ” I know the

sentence that is going to be passed on me.

Before your Honor passes it, I would like

you to understand that I am an innocent

man. I hope before you depart from this

world that you will find I am an innocent

man.”

James Kenniff was then asked if he had

anything to say. He replied : Yes, your

Honor, I wish to comment upon your summ-

ing up to day. You never gave us one atom

of justice. I have no other witnesses to

call, except Almighty God, to show that I

am an innocent man to-day. I hope when

your Honor shuffles off this mortal coil you

will find I am an innocent man.”

The Chief Justice then intimated to Mr.

M’Grath, prisoners’ counsel that he would

reserve to the Full Court counsel’s points,

namely, that there was no evidence to go to

the jury that the prisoners committed the

murder.

…

Addressing the prisoners, he said he entire-

ly agreed with the verdict of the jury. His

Honor them donned the black cap and passed

sentence of death, adding that the execution

would be respited pending the result of the

appeal to the Full Court.

The prisoners heard the sentence in sil-

ence. They looked at each other, and ex-

changed a few words. Before leaving the

dock they briefly conversed with their coun-

sel, and also shook hands with his business

partner. The prisoners walked from the

dock with firm steps.

Although the Chief Justice told the jury that he entirely agreed with their verdict, he sat, with three other Justices, on the Full Court to determine the questions referred.

The four Justices agreed that there was sufficient evidence to convict Patrick Kenniff.

Three of the four Justices agreed that there was sufficient evidence to convicted James — but Justice Real, in a strong dissent, argued that the police officers may have been shot while Patrick tried to free James, and without James being involved at all.

One of the papers described Justice Real’s dissent as a small detail in an otherwise unanimous conclusion about guilt — but the public did not miss that small detail.

There had been already public concern about the venue for the trial, the special jury, and the newspapers effectively convicting the Kenniffs even before they were arrested.

There was a concert held to raise money for an appeal to the Privy Council — Joe Lesina arguing that murder had not been clearly proven in the case.

Petitions were signed in Rockhampton, Brisbane, Toowoomba, Charters Towers and Townsville.

On the 24th of December 1902, the brothers’ solicitor informed Premier Philp that there would be a petition to the King-in-Council seeking permission to appeal to the Privy Council. On the 31st of December, then Executive Counsel announced that the sentence imposed upon James would be commuted to life imprisonment but that Patrick would be hanged on the 12th of January.

The Government’s attitude, as reported in the Courier, was that it was not controlled by any intention on the part of the prisoners to appeal.

But this show of force or determination, in the case of these men, just served to strengthen the position of the abolitionists in Queensland.

Patrick abandoned his appeal, because he would have been dead before any reply from England.

Despite petitions and deputations and 4000 people standing in heavy rain to hear Joe Lesina speak about how justice would suffer were the execution not postponed — the government — supported by the Courier — was immovable. As a consequence the Kenniffs became heroes and martyrs — ‘poster boys’ for the abolitionists’ cause.

Despite petitions and deputations and 4000 people standing in heavy rain to hear Joe Lesina speak about how justice would suffer were the execution not postponed — the government — supported by the Courier — was immovable. As a consequence the Kenniffs became heroes and martyrs — ‘poster boys’ for the abolitionists’ cause.

So too Arthur Ross, who in 1909 was convicted of the murder of a bank teller. He was 21 and the jury had expressly acquitted him of willful murder and strongly recommended mercy because he was so young. Nevertheless, the government decided to execute him.

On the Saturday before his execution, Albert Hall was filled to overflowing with people calling for the commutation of his death sentence. Petitions containing thousands of signatures were presented to the Governor. A deputation was made to the Premier said to be on behalf of all classes of the community.

The Premier’s reply — that the gallows were a bulwark of society was met with scorn by the Worker – which was the newspaper affiliated with the Labor party — and you will see in the exhibition downstairs the front page of the edition containing the cartoon which was part of the response of the Worker to that comment.

The Worker’s editorial response included this statement — that:

the time has arrived for the enlightened modern spirit to repudiate the grisley gospel of the gallows —

and the editors also praised as a ‘manly and enlightened deliverance’ a sermon by a Methodist minister in favour of the abolition of capital punishment, which had attracted a large crowd.

Less than a year after the execution of Arthur Ross, the sixth Labor-in-Politics convention was held. By now, abolitionists had influence in the party — and without debate, a motion that the abolition of capital punishment should become part of the Party’s general program under the heading of social reform was accepted.

The inner-party battle was won at a time which seemed to coincide with a step up in public opinion in support of abolition. But the issue really lay dormant until Labor was victorious at the polls in 1915.

There was an attempt to abolish capital punishment in 1916 by the deputy minister for justice. I won’t go into the detail of it — other than to say that it was defeated in the Legislative Council and in any event the public were not particularly interested in it — perhaps because there had been no executions since Labor assumed power.

More momentum built from about 1920.

At the Labor-in-Politics convention then, abolition was elevated to the leading plank in the party’s social reform platform.

By 1921, there were sufficient supporters nominated to the Legislative Council for it to abolish itself.

The first unicameral Parliament opened in Queensland in 1922 & the Labor government immediately introduced the Bill to abolish capital punishment.

In April of that year, when a child murderer was hanged in Melbourne, the Worker ensured that the Labor party’s political agenda was complemented by carrying a feature article calling for the abolition of capital punishment accompanied by an emotive cartoon about the horror of execution — and that cartoon is in the display.

Clearly, the time was ripe & the bill passed by 33 votes to 30.

Statements made against the Bill were to the effect that the Executive could use their prerogative to deal with doubtful convictions, but those who violently killed were a cancer of society and the only thing to do with them was to get them out of the road. It was argued that violent killers were afraid of death and that fear was their greatest deterrent.

Part of the argument of the then Attorney General, John Mullan, in support of abolition included this:

Hanging has proved to be a failure; it is merely a survival of the primitive instinct for revenge and it is time that capital punishment was abolished. We should be more humane and adopt a more humane method. A more humane method would be to inflict the penalty of imprisonment for life. I believe that, as a result of more humane laws in connection with this matter, and more humane methods generally, and more liberal education, together with an improvement in our social conditions, we will do more to mitigate and eliminate horrible crimes than we can do by other means.

As we know, the bill passed and received Royal Assent on the 31st of July, and the hangman was shown the exit as depicted in the cartoon on the front page of the Worker on July 27, 1922, which is the last piece in the exhibition downstairs.

As we know, the bill passed and received Royal Assent on the 31st of July, and the hangman was shown the exit as depicted in the cartoon on the front page of the Worker on July 27, 1922, which is the last piece in the exhibition downstairs.

So with slim majority political will and power and an elevation in moral tone and compassion and humanism in the community and martyrs to the cause, Queensland became the first State in the British Empire to abolish capital punishment.

Thank you.

Soraya Ryan QC

Intro image (top): James and Patrick Kenniff

Stetch: Crowds gathered outside the Supreme Court building in George Street, Brisbane, for the Kenniff trial – from Sunday Truth newspaper, 9 November 1902

Photograph right (bottom): The Hon Justice Hugh Fraser, Soraya Ryan QC and the Hon IDF Callinan AC QC taken at the Oration to open the Supreme Court Library’s Path to Abolition exhibition in the Sir Harry Gibbs Legal Heritage Centre.

Despite petitions and deputations and 4000 people standing in heavy rain to hear Joe Lesina speak about how justice would suffer were the execution not postponed — the government — supported by the Courier — was immovable. As a consequence the Kenniffs became heroes and martyrs — ‘poster boys’ for the abolitionists’ cause.

Despite petitions and deputations and 4000 people standing in heavy rain to hear Joe Lesina speak about how justice would suffer were the execution not postponed — the government — supported by the Courier — was immovable. As a consequence the Kenniffs became heroes and martyrs — ‘poster boys’ for the abolitionists’ cause. As we know, the bill passed and received Royal Assent on the 31st of July, and the hangman was shown the exit as depicted in the cartoon on the front page of the Worker on July 27, 1922, which is the last piece in the exhibition downstairs.

As we know, the bill passed and received Royal Assent on the 31st of July, and the hangman was shown the exit as depicted in the cartoon on the front page of the Worker on July 27, 1922, which is the last piece in the exhibition downstairs.