FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 100: June 2025, Reviews and the Arts

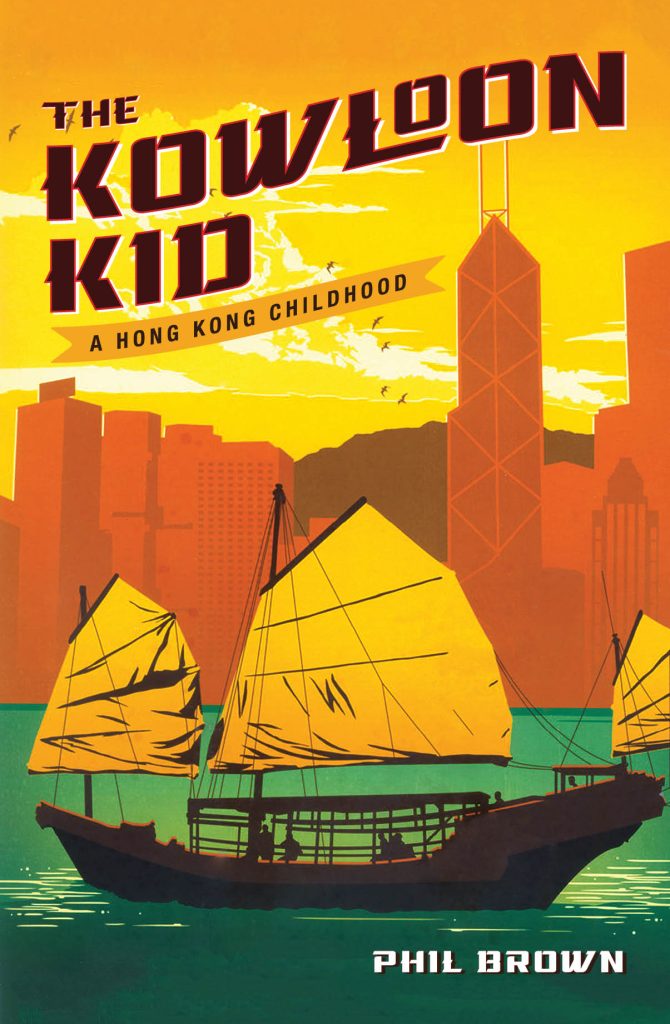

Author: Phil BrownPublisher: Transit LoungeReviewer: Stephen Keim

Phil Brown, who lives a few streets from me, will be known from his writing to many of Hearsay’s readers. Many will know his work as long time Arts Editor of the Courier-Mail and many from his column in the Brisbane News.

Kowloon Kid is a memoir which focuses mostly, but not exclusively, on a patch of Brown’s childhood, from 1963 to 1970, during which Brown, born in 1956, lived the privileged life of a child of Empire among the primarily Asian population of what was still one of the last outposts of that same Empire.

Brown was born in 1956. He had, until the family’s uprooting and transfer to Kowloon, to further Brown’s father’s construction business, lived in the relatively small Hunter Valley town of Maitland in New South Wales. After the seven years in Hong Kong, the family moved back to live on the Gold Coast in Queensland requiring Brown to return to the persona and lifestyle of an Aussie teenager.

Very few people have had seven of their formative years spent in the exotic environs of Hong Kong sandwiched between years of mundanity, living in Australia. It is not surprising that Brown retains a deep love of those years of his childhood as well as great affection for and deep interest in Hong Kong, itself, now a unique outpost of the Middle Kingdom.

Kowloon Kid opens on one of Brown’s many visits back to Hong Kong in the company of his wife, Sandra, and their son, Hamish. Suffering from a bad case of flu, Brown is feeling sorry for himself in the lobby of the Peninsula Hong Kong Hotel, a place of refined luxury, hosting the remains of the Hotel’s famous High Tea.

It turns out that the Peninsula is a symbol of the life that the Brown family lived in the sixties. The same lobby doubled as Brown senior’s de facto business office where Brown senior not only conducted his appointed meetings but, also, hailed fellow well met movie stars and states people and any other famous or interesting person who happened to be, otherwise, having a quietly anonymous time within the lobby’s classy and classical décor.

Brown and his siblings were also familiar with the Peninsula dining there with their parents on a regular basis.

Brown introduces the reader to a number of other famous institutions of Kowloon among them the Kowloon Cricket Club. Not unlike the Peninsula, the Cricket Club was a familiar destination for Brown and his siblings as children. Also, characteristically, the Cricket Club displayed the type of self-importance and stuffy traditions which hundreds of years of empire is particularly good at developing.

Just as Brown introduces the reader to the Peninsula through his illness (accompanied by Sandra’s skepticism developed through years of Brown’s hypochondria), Brown’s contemporary experience of the Cricket Club is ventilated through his embarrassment and annoyance at being called to account for breaching the stuffy tradition that receiving phone calls is strictly off limits in the green and pleasant land that is the Cricket Club.

Brown’s narrative technique is recognisable for his self-deprecation and his use of the much more recent past to give contemporary relevance to the distant past (the focus of the narrative). And, Brown, the likeable fool who makes so many missteps to the scorn of loved ones doubling as travel companions, is a source of humour that shines throughout the text and gives a lightness and interest to the essential narrative.

Kowloon Kid is not just about respected institutions of the Empire. The ordinary and daily life of Brown and his siblings as children living in Kowloon is as important as the streetscape and the institutions. As was de rigeur for Europeans living in Hong Kong, the Brown family had servants. The children had closest contact with their amahs or child minders who looked after them on an ongoing basis. Despite this close contact, Brown marvels at his complete lack of knowledge of anything about Ah Chan and Ah Moy, the two amahs who, between them, served the family for most of the seven years. Amahs traditionally wore a “uniform” of black and white clothing. They were wholly dependent on their employer family so that, if an Australian or British family transferred back to their country of origin, the amah may have faced a lengthy period without employment.

Brown’s years in Hong Kong almost coincided exactly with the years in which the Beatles were a band. Brown’s love of rock music in general and the Beatles in particular is a highlight of those years. Kowloon Kid details the occasions when singles and albums became available for the first time on the streets of Kowloon as well as the experiences of Brown and his friends in discovering the magic that lay within those discs. He reminds the reader that the White Album was actually called, simply, The Beatles” and that it was the world of fans who christened it by reference to the defining colour of the album cover.

Rock music was not just a listening experience. A group of school friends, led by an American friend of Brown, formed a group and performed, at the invitation of a cool and empathetic teacher, on one occasion only, a number of popular songs of the time. The Hutchence family, including young Michael, were friends of the Brown children and Michael and Brown attended the same school. In his characteristic, self-mocking manner, Brown suggests that, not only was he a performing rock star years before Michael Hutchence, but, just maybe, it was Brown’s musical prowess that inspired the young Hutchence to the major musical successes he experienced before his tragic death.

Kowloon Kid covers a lot of bases. It documents, beautifully, long past days of empire ambience in one of the world’s great cities. For boomers, it evokes a beautiful nostalgia for those days when we were young and, despite our youth, we knew everything. It also conveys a humorous but empathetic tale of family life in which trivial events carry importance for individuals and the people they love.

Kowloon Kid was published in 2019. Brown has another book being launched at Queensland Writers Festival in October 2025. Kowloon Kid is a very enjoyable read. But, despite the lightness of its tone and narrative, it is an important book, as well.