FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 95: March 2024, Reviews and the Arts

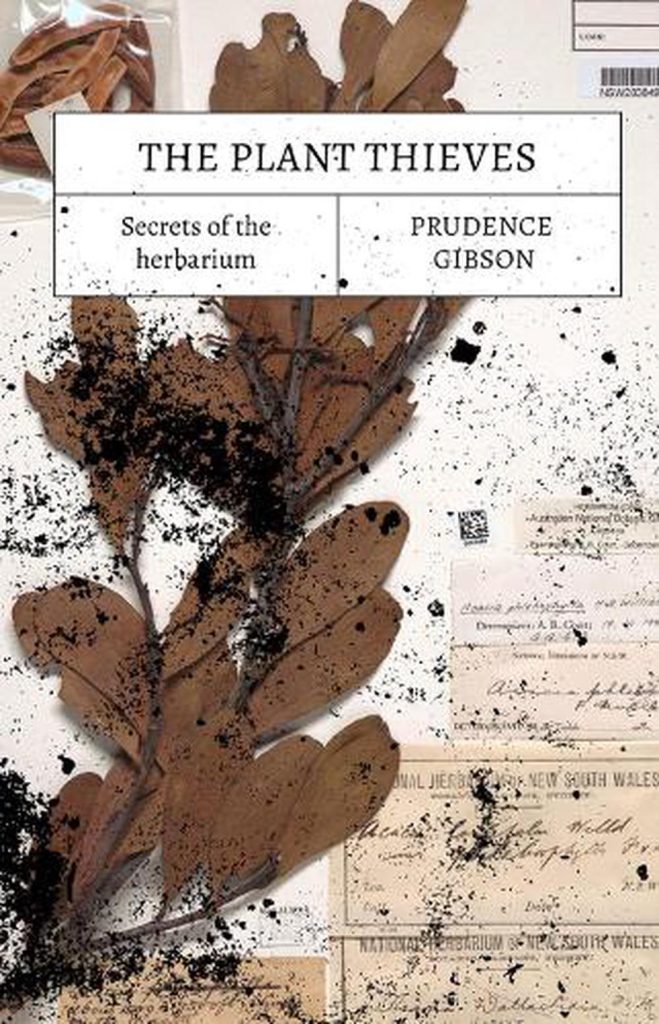

Author: Prudence GibsonPublisher: New South PublishingReviewer: Stephen Keim

The Plant Thieves (“Plant Thieves”) is one result of a project challenging the discipline boundaries within which expertise is usually exercised. The project, Exploring Botanic Gardens Herbarium’s Value via Environmental Aesthetics, was a collaborative effort funded by the Australian Research Council’s linkage program. It linked academics from the Universities of New South Wales and Melbourne and staff of royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust and of the Bundanon Trust.

The author of Plant Thieves, Prudence Gibson, as an author and research academic in plant studies at the School of Art and Design at the University of New South Wales, is well-qualified to bring aesthetic sensibilities to the botanical world.

Originally designed to explore the aesthetics of the National Herbarium of New South Wales’ plant collection, the project took place during and after the collection’s move to a new facility at the Australian Botanic Gardens at Mount Annan. As a result, Plant Thieves manages to document many of the challenges and revelations of a momentous moving process along with the subtleties and revelations of a digitisation process of all the information held about all the 1.4 million plants in that huge and priceless collection.

Gibson, from the beginning of Plant Thieves acknowledges the political and moral questions that surround an institution that seeks to advance knowledge and human welfare by maintaining a collection of plants but has achieved its collection and status accompanied by and part of aggressive colonialism of a continent whose Indigenous owners and inhabitants, themselves, lived extremely closely with their environment and whose purpose in life was to care for that environment in every aspect of the way in which they lived their lives.

Every visitor to the British Museum considers themselves attending in the virtuous appreciation of knowledge and history. Every such visitor must, at some time, however, face the question whether, by crossing that threshold, they make themselves a party to the theft of the Elgin Marbles and, perhaps, many other objects in the collection.

So it is with the Herbarium.

As Gibson expresses it, the Herbarium’s collection is the epitome of the colonialist fervour to collect and dominate nature. Part of the inextricable relationship between plants and colonialism is all the theft, all the death and all the control exerted over land and First Nations peoples that are a part of Australia’s history. And, while the Herbarium is a place of exquisite beauty and holds seeds and secrets of future life, it also records the violence and the damage done to the earth, the trees, the plants and to the very future it promises to secure.

Gibson wrestles with the ugly aspects of botany in colonialist Australia and, as she also states, the Herbarium’s paradoxical role in this regard as taker and keeper is a matter of endless interest.

The project on which Gibson was engaged required her to learn about the Herbarium, its collection and the people who make it work. She also made herself familiar with the “physical matter of the archival documents”. Among the things Gibson learned is that a herbarium is more than an archive. It is a repository for stories: stories which are as much about people as they are about plants. Those stories fill the pages of Plant Thieves.

Gibson explores the colonisation of Australian plants through the juxtaposition of Gamileroi poet, Luke Patterson, who grew up at Kurnell on the shores of Botany Bay playing war games tossing Banksia serrata conesat his playmates and going to school where everything, even the names of the school houses, honoured Captain James Cook and his collector, Joseph Banks. Banks, who took 30,000 specimens from Australian shores continues to be revered as a pioneering botanist including through the honour of having the generic name one of Australia’s most distinctive plant groups named for him. At the same time, while Banksia species were culturally and materially important to Indigenous groups up and down the continent, hardly one Indigenous word has found its way into the official Linnaean manner of grouping and naming plants of this kind.

And as for banksias, so for most Australian plants. The process of colonialism not only dispossessed and murdered Indigenous people, its scientific language erased their existence from most botanical records.

Exploring what might be done to decolonise botany, Gibson spoke to Mbabarram man, Gerry Turpin, an ethnobiologist working in Cairns as an ethno-botanist. Turpin has a plant, a native legume named after him. Turpin is employed by the Tropical Indigenous Ethnobotany Centre to record and document traditional plant use on Cape York Peninsula. Turpin has worked to develop reconciliation action plans which include actions to protect Indigenous cultural and intellectual rights and Indigenous regeneration plans. Such plans use an approach to botany known as two way: Indigenous and Western knowledge working together. Gibson examples Indigenous fire management practice which she identifies as used widely across Australia, especially, since the tragic 2019-2020 bushfires, as a form of two way methodology.

It is encouraging to read of the progress being made in accepting Indigenous knowledge on Indigenous terms to advance the understanding and protection and conservative use of the Australian environment. The work of Turpin and others including Victor Steffensen is important in this regard. Despite such optimism, the work of decolonising environmental science in Australia, including botany, has a long way to go. There are a lot of specimens in the herbarium still bearing the names of the servants of the colonising process including, but not limited to, Joseph Banks.

Gibson’s stories of people and of specimens are well worth telling. They include herbarium librarian, Miguel Garcia, and his love of the zombie fungus, ophio-cordyceps, which sends out its mycelial threads to penetrate and take over the body of insect larvae, keeping them alive while directing the larva, through its central nervous system, to keep on behaving in a way that supports the growth and maturation of the fungus until it is a fruiting body transported conveniently by the larva to the surface to send forth its spores for a new generation of zombies to take over new generations of insect larvae for their own nefarious purposes in the great game of natural selection.

Another example of the fascinating stories of people and plants associated with the herbarium concerns the former head of science at the Herbarium, Barbara Briggs, who rose to that position after starting as a PhD candidate in 1959 but continues to be active in botany, more than six decades, later, aged 87. Briggs’ story is interesting not just for the 80 plants described and named by her but for her enduring interest in people and the world and the enjoyment she continues to obtain from the natural world’s endless variety. Among the tidbits she shared with Gibson is the story of the black wings, English moths which evolved in the 19th century to a deeper shade of dark to ensure their improved safety in a world where pollution ruled the atmosphere.

Almost as a side project, Gibson devotes thirteen chapters and 70 pages to psychoactive plants and the collection of passing strange but fascinating people in the community who value them, grow them and who, occasionally, partake of their psychoactive properties. Some of these people live in the shadows and Gibson’s talent as a journalist who can build trust is attested to by her ability to contact and interview members of the psychoactive botanical community.

Gibson details the legal restrictions on growing and using psychoactive plants and discusses the arguments in favour of society taking a more tolerant attitude to these plants and the people who appreciate them.

Part 3 of Plant Thieves is entitled Rewilding, conservation and creative revaluing. The title suggests ninety pages of evangelism and it is the case that Gibson considers various philosophical and normative issues in part 3.

For every discussion of what might and should be done, however, Gibson produces an accompanying narrative about plants and people that fascinates as much as it instructs.

Anecdote, interest, engagement and fascination are the hallmarks of every page of Plant Thieves. For the reader who has always claimed an interest in plants and botany, Plant Thieves is a pleasant way of continuing that interest and expanding one’s knowledge. Plant Thieves is more than just a collection of plant stories. Along with the anecdotes and the science, accessibly presented, every page also raises questions for the reader that survey deeper issues and challenge us to question deeply held but unconsidered beliefs such as our unthinking hero worship of the Joseph Bankses of our growing years without a thought for the people from whose land they were gathering their specimens.