FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 46 Articles, Issue 46: Dec 2010

Introduction

In 1995, the then new Trade Marks Act 1995 introduced the possibility of registering a shape as a trade mark. Since then there have been a number of cases which have considered this area of trade mark law. A party who has successfully registered a shape mark, and who commenced enforcement proceedings, has usually been faced with the defence that the trade mark is not inherently capable of distinguishing the trader from others, on the basis that the shape is dictated by its function. In other words, it is the shape it is because of functional considerations not because the trader has chosen a mark capable of distinguishing the trader’s goods or services from other traders.

It is fundamental in trade mark law, that a trade mark is a sign1 used to distinguish traders:

A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.2

Coca Cola v Pepsi

Coca Cola v Pepsi

Coca-Cola has several registered trade marks in which the shape of its contour bottle is sought to be protected. The Delaware corporation has, for example, 3 views of the shape registered with the Coca Cola name as mark 1055635 and 4 views of the shape, also with the words, as mark 1057210 :

The endorsement to the registration notes that ‘the trade mark consists of the word COCA-COLA applied to the shape of a silver coloured 3-dimensional bottle as shown in the representations attached to the application form.’

On 14 October 2010, Coca-Cola commenced an action against Pepsi, claiming that Pepsi had in the promotion and sale of its soft drink, taken the shape of the Coca-Cola contour bottle, without authority, and thereby infringed its trade mark.

Coca-Cola said in its statement of claim, that it had been using the contour bottle’s ”distinctive shape and silhouette” since 1938 in Australia. From the 1960s the drink has been sold in cans as well as in the contour bottles. Since the 1970s Coca-Cola has been sold mainly in plastic bottles. Notwithstanding this evolution, the contour bottle has remained a mark or sign, which is readily recognised by its shape alone as the “Coca-Cola” or “Coke” bottle. Since 1994 a significant proportion of the marketing of the Coca-Cola beverage in Australia has used or promoted the image of the contour bottle.3 In Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect, the respondent was a confectionery wholesaler which imported and distributed, amongst other products, cola flavoured confectionary in the shape of a contour bottle ‘somewhat like the contour bottle.’4 One aspect of the primary judge’s decision, successfully appealed by Coca-Cola, was that the confectioner’s use of the contour shape of the confectionary, was a use of the mark as a trade mark. Relevantly, infringement occurs:

“… if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.”5 (underlining added)

With reference to the question as to whether the shape of the confectionary was used as a trade mark, their Honours concluded at [25]:

The confectionary has three features that are not descriptive of the goods. They are the silhouette, the fluting at the top and bottom, and the label band. It is not necessary for the respondent to adopt any of those features in order to inform consumers that its product is a cola flavoured sweet. It could do so by using the cola colour, the word COLA and the shape of an ordinary straight-walled bottle. The silhouette, fluting and band are striking features of the confectionary, and are apt to distinguish it from the goods of other traders. The primary function performed by these features is to distinguish the goods from others. That is to use those features as a mark. It is true, as the respondent said, that the fact that a feature is not descriptive of goods does not necessarily establish that it is used to distinguish or differentiate them. But in the present case we are compelled to the conclusion that the non-descriptive features have been put there to make the goods more arresting of appearance and more attractive, and thus to distinguish them from the goods of other traders. (Underlining added)

The relevance to the recently commenced proceeding will no doubt be that if the court has found that the contour shape is capable of being used as a trade mark by a respondent, for the purpose of that element of infringement, then that must go a long way to assisting Coca-Cola argue that the contour shape is not dictated by function and that there are choices behind the contour shape, which have been designed to make the goods more appealing, thereby capable of distinguishing the goods of Coca-Cola from other traders.

Directions were given in the matter by Dodds-Streeton J of the Federal Court of Australia, ordering a pleading schedule, exchange of categories of documents for discovery and a separate the hearing in relation to liability issues before issues of quantum are heard. The matter is listed for further directions in April 2011.

Other attempts to register or defend shape marks have been: Rodney Gibson [2010] ATMO 73 (Delegate Thompson, 12 August 2010) in respect of shapes relating to transportable buildings; Chocolaterie Guylian N.V. v Registrar of Trade Marks [2009] FCA 891 (18 August 2009) in respect of the sea-horse shape of the Guylian chocolate range; Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v Nestle Australia Ltd [2010] FCA 198 (10 March 2010) (Trial Judge) Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v Nestlé Australia Ltd [2010] FCAFC 117 (Full court) in respect of a sweet named ‘luscious lips’. Appeal the Full Court affirmed the Sundberg J’s decision that the respondent’s use was descriptive of the candy not a use as a trade mark, offending the applicant’s registered trade mark; World Brands Management Pty Ltd v Cube Footwear Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 769 (Heerey J, 4 June 2004) regarding the shape of a shoe (interlocutory application for injunctive relief).

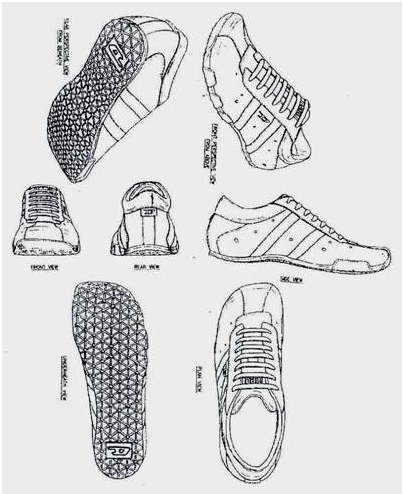

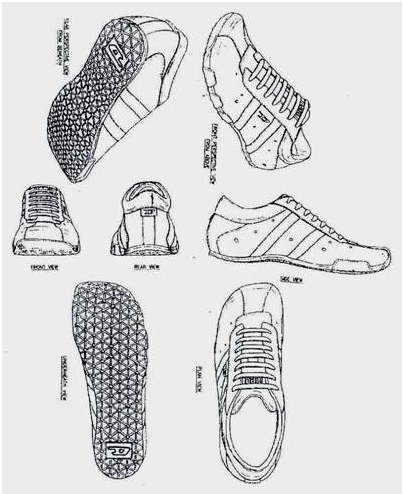

Certainly if one registered a shape mark, and that shape contained some identification of the trader such as a large capital ‘D’, it could be expected that a copying of the shape and the capital ‘D’, would put the motive of the respondent in question. This was the case in Global Brand Marketing Inc v YD Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 605 (7 May 2008). In that case the trade mark was the following depicted shape:

Sundberg J observed at [117]f, in relation to Diesel shape mark:

“Diesel does not claim a sole as such. Rather the claim is to a diamond shaped pattern with a panel containing a stylised D. That combination is such that by its use Diesel is likely to attain the object of distinguishing its Trainers from those of others. In addition, other traders in Trainers would not reasonably want to apply the sole mark to their own goods, especially as it incorporates Diesel’s D.

YD’s cross claim based on s 41 fails.”

Comment

In the author’s view, these cases give rise to public policy considerations. In copyright, one concern of government was the copyright protection afforded to a three dimensional version of a two dimensional artistic work. For example, a drawing of chair has copyright protection. The protection was the life of the author plus 50 years, now 70. A three dimensional version of the two dimensional drawing, the chair, had copyright protection for the same period.

Government considered that this was an unreasonable protection for what was effectively a design and would under the then Designs Act 1906, only have protection for a total of 16 years (s 27A of the 1906 Act). Of course the Designs Act had a requirement of being ‘new or original’. Effectively, a person could get a monopoly in a design for the life of the designer/author plus 50 years.

Accordingly, ss 74 -77 of the Copyright Act 1968 came into effect, providing a defence to copyright claims for such industrially applied corresponding designs.

The trade marks scenario should pose in theory a greater mischief. A trade mark registered as a shape mark, would give a perpetual right of ownership in a shape. A shoe design for example, if registered as a shape mark, effectively gives a perpetual monopoly in the shoe.

The ‘release valve’, however with trade marks, is the consideration that if other traders acting reasonably and with proper motives, would be entitled to use the mark, it will lack distinctiveness under s 41 of the Trade Marks Act. This however, may be overridden by satisfactory evidence of use leading to the applicant’s goods or services acquiring distinctiveness: (ss 41(5) and (6).

By Dimitrios Eliadis

Footnotes

- As defined in s 6 of the Trade Marks Act 1995

- Trade Marks Act 1995 s 17.

- As per (the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia in Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 43 IPR 47 (Trial Judge); (1999) IPR 481; [1999] FCA 1721 (Full Court) at [7].

- Full Court at [2].

- Trade Marks Act 1995 s 120.

Coca Cola v Pepsi

Coca Cola v Pepsi