I commence by acknowledging the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land on which we are meeting this morning. That acknowledgment is a reminder of the role which law played in the traditional societies of Australia’s indigenous people. Years ago, when the people of north¬eastern Arnhem Land claimed an entitlement to their land to protect their heritage, Blackburn J, in a judgment which was constrained by the law as it was then understood, commented1 that —

“The evidence shows a subtle and elaborate system highly adapted to the country in which the people led their lives which provided a stable order of society and was remarkably free from the vagaries of personal whim or influence. If ever a system could be called ‘a government of laws, and not of men’, it is that shown in the evidence before me.”

His Honour’s finding identifies the indicia of the rule of law. It is a system which is appropriate to serve the people of a society, it provides a stable order, it is free from the vagaries of personal whim or influence. Power is controlled not by the dictates of powerful people but by “a subtle and elaborate system”. Western societies boast of the rule of law but traditional societies may also be governed by the rule of law although colonization and the impact of western civilisation have reduced the number of traditional societies and have replaced or at least modified their legal systems. Legal systems necessarily vary from place to place, from people to people, for each system must respond to local culture and conditions. But whatever be the character of a legal system, the rule of law is the underpinning of peace, order and freedom.

Today’s Conference on the rule of law is timely. It is time to understand what it is and what it does, to appreciate the institutions which are responsible for applying the rule of law and to identify the characteristics of the rule of law which ensure its support and continuance. It is time to examine these issues to correct misunderstanding.

A misunderstanding which is sometimes heard is that the rule of law is a mere catch-cry uttered by lawyers in some fictional contest for power between the Judiciary and the Executive. It is nothing of the sort. The Judiciary does no more than apply the law to the Executive government as it does and as it is bound to do to every other element in the community. In the Communist Party Case2, Dixon J observed that among the traditional conceptions in accordance with which our Constitution is framed “it may fairly be said that the rule of law forms an assumption.” There is no contest for power. There may often be tension between those branches of government, and so there should be. If it happens, as it sometimes does, that the Executive government exceeds or misapplies its power and the unlawful exercise of its power is set aside by an order of a court, the Executive government may well feel frustrated, but that is simply the effect of the law. Judges no less than the Executive and its agents, are subject to the rule of law. The tension between the Executive and the Judiciary is not a solely Australian phenomenon. Lord Bingham of Cornhill, the senior Law Lord, in a wide-ranging analysis of the rule of law3 stated the British experience:

“Some sections of the press, with their gift for understatement, have spoken of open war between the government and the judiciary. This is not in my view an accurate analysis. But there is an inevitable, and in my view entirely proper, tension between the two. There are countries in the world where all judicial decisions find favour with the government, but they are not places where one would wish to live. Such tension exists even in quiet times. But it is greater at times of perceived threats to national security, since governments understandably go to the very limit of what they believe to be their lawful powers to protect the public, and the duty of the judges to require that they go no further must be performed if the rule of law is to be observed. This is a fraught area, since history suggests that in times of crisis governments have tended to overreact and the courts to prove somewhat ineffective watchdogs4.”

If the rule of law is the basis on which the Judiciary reviews administrative action as well as the foundation of order in our society, we should understand what the term means. A.V. Dicey5 gave this as the primary meaning —

“the absolute supremacy or predominance of regular law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power… Englishmen are ruled by the law, and by the law alone; a man may with us be punished for a breach of law, but he can be punished for nothing else. It means, again, equality before the law or the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land administered by the ordinary law courts; the ‘rule of law’ in this sense excludes the idea of any exemption of officials or others from the duty of obedience to the law which governs other citizens or from the jurisdiction of the ordinary tribunals.”

The law regulates complex relationships — relationships between people and relationships between the people and the state. In a society governed by the rule of law, special knowledge and skills are needed to administer a “subtle and elaborate system”. Competence, as well as authority, was the concern of Lord Coke’s famous rejection in the case of Prohibitions Del Roy6 of King James I’s pretensions to judge:

The law regulates complex relationships — relationships between people and relationships between the people and the state. In a society governed by the rule of law, special knowledge and skills are needed to administer a “subtle and elaborate system”. Competence, as well as authority, was the concern of Lord Coke’s famous rejection in the case of Prohibitions Del Roy6 of King James I’s pretensions to judge:

“His Majesty was not learned in the laws of his realm of England, and causes which concern the life, or inheritance, or goods, or fortunes of his subjects, are not to be decided by natural reason but by the artificial reason and judgment of law, which law is an act which requires long study and experience, before that a man can attain to the cognizance of it: that the law was the golden met-wand and measure to try the causes of the subjects; and which protected His Majesty in safety and peace.”

That is why lawyers are essential to the rule of law. The basic assumption of the rule of law is that the law is truly defined. Under the common law system, definition of the law is the ultimate responsibility of the courts. In the familiar words of Chief Justice Marshall in Marbury v Madison,7 “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is”. One may add “the judges assisted by the legal profession”. Or, as Lord Bingham pointed out in A v Secretary of State for the Home Department8 —

“…the function of independent judges charged to interpret and apply the law is universally recognised as a cardinal feature of the modern democratic state, a cornerstone of the rule of law itself.”

The declaration of the law is a basic, but not the only, element in the operation of the rule of law. Much depends on the terms in which the law is framed and on the manner in which it is applied. A literal application of laws which trample on basic human rights may be the very antithesis of the rule of law. Some of Hitler’s heinous policies were implemented in accordance with German law as it then was. There is a difference between the rule of law and rule by law. In a recent speech, the British Attorney-General, Lord Goldsmith QC, said that the rule of law —

The declaration of the law is a basic, but not the only, element in the operation of the rule of law. Much depends on the terms in which the law is framed and on the manner in which it is applied. A literal application of laws which trample on basic human rights may be the very antithesis of the rule of law. Some of Hitler’s heinous policies were implemented in accordance with German law as it then was. There is a difference between the rule of law and rule by law. In a recent speech, the British Attorney-General, Lord Goldsmith QC, said that the rule of law —

“is not simply about rule by law. Such a proposition would be satisfied whatever the law and however unfair, unjust or contrary to fundamental principles, provided only that it was applied to all. Instead it seems to me clear that the rule of law comprehends some statement of values which are universal and ought to be respected as the basis of a free society.”9

That requires a commitment to the rule of law by the legislature and the executive as well as by the judiciary. So much was recognized by Lord Goldsmith who added —

“In my view all the organs of state — the executive, legislature and judiciary — have a shared responsibility for upholding the rule of law. This is not to down play the responsibility of the courts — they provide the critical long-stop guarantee — but the rule of law will only have real meaning in practical terms in a society in which all organs of the state are mindful of their obligations to respect it.”

This theme about the content of the law was taken up by Lord Bingham when he said that the rule of law means, inter alia, “that the law must afford adequate protection of fundamental human rights”, although he accepted that there is “an element of vagueness” about that proposition.

In this country, in the absence of a constitutional Bill of Rights, fundamental human rights are susceptible to extinction by statute. It is surely the function of lawyers to be able to identify laws which have that effect, to seek to have them narrowly applied and to contribute to any public consideration of the necessity for enacting or retaining such laws. There must be an overriding justification of public interest to warrant a denial of any person’s fundamental human rights. That proposition presents today’s lawyers with a significant challenge to keep the law respectful of human rights so far as is compatible with the national interest.

A peaceful and ordered society needs the rule of law but it also needs to be secure against disruption from both external and internal sources. How are these two needs to be satisfied or, if not satisfied, reconciled; or, if not reconciled, balanced? Perhaps the answer is to be found in what it is that sustains the rule of law. Most lawyers are familiar with the danger created by ordinary criminal conduct and, over the years, the courts and the legislature have prescribed the steps to be taken in detecting and punishing crime and the procedures and penalties which are intended to suppress it. But lawyers generally do not know the true nature and extent of the threat posed by terrorism today and, like many others, are uncertain about the steps which should be taken to suppress it. What lawyers do know, however, is what laws, practices and procedures provide the safeguards which maintain public confidence in the rule of law. When the conventional safeguards of law and the legal process are dismantled or reduced so that the public sense that justice according to law is no longer assured to all people within the jurisdiction, public confidence in the rule of law is lost or diminished. That weakens the unity and fabric of society and exposes us to danger from those who do not share a respect for the rule of law.

A peaceful and ordered society needs the rule of law but it also needs to be secure against disruption from both external and internal sources. How are these two needs to be satisfied or, if not satisfied, reconciled; or, if not reconciled, balanced? Perhaps the answer is to be found in what it is that sustains the rule of law. Most lawyers are familiar with the danger created by ordinary criminal conduct and, over the years, the courts and the legislature have prescribed the steps to be taken in detecting and punishing crime and the procedures and penalties which are intended to suppress it. But lawyers generally do not know the true nature and extent of the threat posed by terrorism today and, like many others, are uncertain about the steps which should be taken to suppress it. What lawyers do know, however, is what laws, practices and procedures provide the safeguards which maintain public confidence in the rule of law. When the conventional safeguards of law and the legal process are dismantled or reduced so that the public sense that justice according to law is no longer assured to all people within the jurisdiction, public confidence in the rule of law is lost or diminished. That weakens the unity and fabric of society and exposes us to danger from those who do not share a respect for the rule of law.

Lawyers should be, and often are, involved in the process of making our laws. Apart from their engagement in politics, they can explain how the rule of law is impaired by dismantling or reducing the conventional safeguards of law and the legal process. The lawyer’s public role, I suggest, is to advocate the importance of preserving the safeguards of the rule of law unless it is tolerably clear that any proposed abrogation of the traditional laws, practices and procedures is necessary to protect the community, that the abrogation is proportionate to the apprehended harm and has a substantial prospect of achieving the desired protection.

Let us then reflect on some of the key features of our system which establish and sustain the rule of law. It matters not that the public does not consciously advert to some of these features; after all, we do not consciously think about the air we breathe. But if any of us were caught in the toils of a system which denied the rule of law, we would surely be conscious of what we had lost. By reminding ourselves of characteristic features of the rule of law, we can identify the risk to our freedom which is posed by any law or practice which eliminates or diminishes those features.

1. Public promulgation of laws made by the democratic process

To maintain confidence in the rule of law, the laws must be publicly promulgated. Retrospectivity is incompatible with the rule of law. It denies the freedom which individuals are entitled to enjoy subject to conformity with the law. It unbalances the relationship between the government and the governed. If we accept that the moral authority of the law comes from the people, the people must have the ability to reject the laws by changing the lawmakers. The rule of law is not possible, in my view, if the people cannot change the law. In a democracy, a dissident minority agrees to be bound by laws from which that minority dissents and that minority is free to express dissent. Absent that right, dissent festers until expressed in disruptive protest.

The right to peaceful dissent is not merely something to be tolerated. It is an important safeguard of peace and order; it is a feature of a free society under the rule of law. Subject to the ordinary laws governing the limits of free speech, restriction on the freedom to dissent or to contribute fairly to political discussion10 is an impairment of the rule of law.

2. The public administration of the law

The public requires assurance of the proper application of the law, so the courts must conduct their proceedings in public. In 1913, the High Court said11 that the admission of the public to attend proceedings is “one of the normal attributes of a court”. Stephen J (as Sir Ninian then was) in Russell v Russell12 said that “a tribunal which as of course conducts its hearings in closed court is not of the same character as one which habitually conducts its proceedings in open court”. Public scrutiny of curial proceedings gives the assurance of integrity in the application of the law. The administration of the law is a public function and secret trials lead inevitably to injustice. To quote Sir Frank Kitto:13

“The process of reasoning which has decided the case must itself be exposed to the light of day, so that all concerned may understand what principles and practice of law and logic are guiding the courts, and so that full publicity may be achieved which provides, on the one hand, a powerful protection against any tendency to judicial autocracy and against any erroneous suspicion of judicial wrongdoing and, on the other hand, an effective stimulant to judicial high performance. Jeremy Bentham put the matter in a nutshell … when he wrote …:

‘Publicity is the very soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion and the surest of all guards against improbity. It keeps the judge himself while trying on trial’.”

3. The application of the law must be, and be seen to be, impartial

Impartiality is the supreme judicial virtue.14 It regulates the conduct of the proceedings, the evaluation of evidence, the conclusion of facts and the analysis and application of legal rules. It guarantees that equality of treatment which is at the heart of the rule of law. It is a fundamental precept that the courts must act impartially between the parties.15 Professor Winterton, commenting on the Communist Party Case,16 said that it

“demonstrated that our freedom depends upon impartial enforcement of the rule of law, of which courts are the ultimate guardians. Although, of course, not infallible, impartial and fearless courts determined to exercise their proper powers are our final defence against tyranny.”17

The appearance of impartiality is as critical to the confidence reposed in the courts as impartiality itself. Lord Devlin pointed out that —

“[t]he Judge who does not appear impartial is as useless to the process as an umpire who allows the trial by battle to be fouled or an augurer who tampers with the entrails.”

No unsuccessful party should be left with any reasonable apprehension of bias affecting the decision. Nor should the public have any ground for concern on that score. For that reason, the courts themselves have laid down the rule18 that a challenge to a decision on the ground of bias will succeed if “in all the circumstances the parties or the public might entertain a reasonable apprehension that the judge might not bring an impartial and unprejudiced mind to the resolution of the matter before him”.19 To ensure impartiality it is essential that a judge be independent — independent of those who can confer a benefit or cause a detriment, independent of politics or power, independent of influences that might inappropriately affect the performance of the judicial function.

4. Natural justice must be observed

In Leeth v The Commonwealth,20 the majority observed that —

“it may well be that any attempt on the part of the legislature to cause a court to act in a manner contrary to natural justice would impose a non-judicial requirement inconsistent with the exercise of judicial power.”

The observance of natural justice, or procedural fairness, is not an obligation imposed only on the exercise of judicial power. We are familiar with this requirement in the review of administrative action and, to the legal professional, it is axiomatic. Natural justice requires, inter alia, that a party whose interests might be affected by a decision must be heard before the decision is made and must have an opportunity to answer any adverse material which might affect the decision to be made When statute exempts any repository of power from the obligation to observe natural justice, an exercise of the power is attended with the risk of injustice — injustice which is not curable by judicial intervention and which may not even be revealed if the repository of the power does not have to disclose the material on which he or she acted.

5. Justice must be done according to law

The judicial function is not merely to interpret but also to apply the law. The judicial method of reasoning is calculated to ensure that, in the application of the law, justice is done as far as is consistent with the law. The rules of statutory interpretation, for example, are designed to preserve fundamental human rights so far as is consistent with the language of the statute. The freedoms and immunities recognized by the common law are not denied unless the language of the statute so demands. This approach led a Cambridge academic, R W M Dias,21 to comment that, in the application of legal rules —

“…it is commonplace that… [the judges] are guided by their sense of values according to which they balance the interests in dispute.

This explanation, brief as it is, makes it possible to relate judicial independence to the ‘rule by law’/’rule of law’ dichotomy. Where ‘rule by law’ obtains, the judiciary is a tool of government, which, along with others, reflects and implements official policies and interests. Where ‘rule of law’ obtains, judges are free to decide on values of their own, and the check on power derives from their being able to hold governmental interests in balance against others. In this way the British judiciary has built up its tradition of independence over the centuries. By and large judges have contrived to preserve as much balance of power in society as they could by siding with the weaker side whenever the balance tilted against it.”

Dias is mistaken in his phrase “values of their own”: Judges do not purport to apply their idiosyncratic values, but rather to give expression to those deep and enduring values of the community which, in large measure, inform the common law. An exercise of the leeway which judges have in applying the law requires as much assistance from the legal profession as the ascertainment of a legal rule.

6. The law must be applied universally

The law must be applied to all, subject only to exceptions that are justified by a relevant and reasonable ground of differentiation. If it were otherwise, the distinction between those covered by the law and those who are not would be a source of discontent, if not oppression. The law would not rule, that is, it would not govern the conduct of all or order the relationships of individuals or of individuals with the State. In the Supreme Court of the United States, Justice Jackson observed22 that:

“The framers of the Constitution knew, and we should not forget today, that there is no more effective practical guaranty against arbitrary and unreasonable government than to require that the principles of law which officials would impose upon a minority must be imposed generally. Conversely, nothing opens the door to arbitrary action so effectively as to allow those officials to pick and choose only a few to whom they will apply legislation and thus to escape the political retribution that might be visited upon them if larger numbers were affected. Courts can take no better measure to assure that laws will be just than to require that laws be equal in operation.”

The law must apply equally to all since, as John Locke pithily observed:

“Where-ever law ends, tyranny begins.”23

Thus it has been held that the criminal law applies equally to all, including those who purport to act in breach of the law under the authority of the executive government24.

If the rule of law is to apply universally, the jurisdiction of the courts to judicially review an exercise of administrative power is essential. To the extent that the courts are denied jurisdiction to review judicially an exercise of administrative power, the power is beyond control by operation of law. If the courts are denied jurisdiction to enforce the law governing the exercise of power, the repository of the power can refuse to obey the law with impunity and the rule of law is negated. By reason of s 75(v) of the Constitution, however, decisions taken in exercise of federal power cannot be totally exempt from judicial review. As the High Court pointed out in Plaintiff S157/2002,25 the jurisdiction conferred on the High Court by that provision —

“is a means of assuring to all people affected that officers of the Commonwealth obey the law and neither exceed nor neglect any jurisdiction which the law confers on them. The centrality, and protective purpose, of the jurisdiction of this Court in that regard places significant barriers in the way of legislative attempts (by privative clauses or otherwise) to impair judicial review of administrative action. Such jurisdiction exists to maintain the federal compact by ensuring that propounded laws are constitutionally valid and ministerial or other official action lawful and within jurisdiction.”

The Role of the Legal Profession

I have spoken chiefly of the role of the courts in the maintenance of the rule of law. The ultimate responsibility for maintaining the standards, practices and procedures which are the critical aspects of the rule of law rests with the judiciary. But the courts are the long-stop. The law which rules is the law according to the rulings of the courts, but it is applied in the offices and chambers of the legal profession. It is applied in drafting and advising; in consultations more than in litigation. But, because the courts are the long-stop and because the rulings of the courts determine the way in which the law operates, judicial decision-making is critical to the maintenance of the rule of law. So it is in litigation that the practising legal profession works at the cutting edge of the rule of law. They are the initiators who produce the evidence and frame the issues for determination; they are the principal officers involved in the testing of evidence and honing the issues for judicial consideration; they are the researchers who identify the statutes and the precedents and whose submissions assist in ascertaining the facts and applying the relevant law or, on occasions, in exercising a judicial discretion.

To perform their appointed function, the members of the practising profession must be knowledgeable in the law and competent in its application. It is not sufficient to be mere technicians, familiar with the words of a statute or a precedent. There may be a need to understand the underlying purpose of the statute or the principle to which the precedent is giving effect. The law develops organically and incrementally, and the legal profession usually provides the stimulus to its growth. The advocate, respectful of judge, witness and opponent but fearless in advancing the client’s case, is the daily witness to the work of the judiciary. In that role, the advocate is bound not only to assist in the elucidation of relevant fact and law but to ensure and defend the impartial discharge of judicial duty. Misbehaviour by a judge is antithetical to the rule of law and, at whatever cost, the advocate’s duty is, firmly but respectfully, to propose a return to judicial propriety. It is a commonplace that judges acknowledge the important role which advocates play in the dispensing of justice according to law. To perform that function, the advocate must be independent of any influence that might tend towards a deviation from an advocate’s duty — even the influence of the client to whom a duty is owed, which is a duty subordinate to the duty to the court.

Outside the Court, the legal profession has a role to play in the framing of our laws. Individually and institutionally, the legal profession can seek to ensure that the values of the common law are preserved to the extent possible at a time when we are concerned by the threat of terrorism. That is not to suggest that it is the function of the institutional profession to oppose any law simply because it trespasses upon one of the values of the common law. When laws enacted within power do abrogate the ordinary safeguards of the rule of law, it is the function of the practising profession to apply them according to their terms, construing them by established canons of construction. Thus is the rule of law preserved to the extent that it is legally possible to do so. But it should be remembered that, over the centuries, the common law balance of individual freedom and community protection is the balance which the community has accepted as appropriate in an ordered but free society. Only a modicum of freedom can be traded for security without affecting the rule of law. When new incursions are to be made on individual freedom or the values of the common law are to be trespassed upon in some way, some justification must be shown. In recent times, the Parliament has enacted laws which make substantial incursions on individual freedom and the values of the common law.

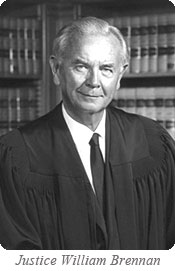

Under the Australian Security Organization Act 1979,26 some persons may be detained without any suspicion of their being involved in the commission of any offence; their detention may be authorized on the basis of information of which they have no knowledge; orders can be made in secret without public access or accountability. And the Commonwealth Criminal Code27 allows the making of control orders against persons who may not have committed any offence if the order is thought to be reasonably necessary to protect the public from a terrorist act. Incursions on the rule of law may be essential to combat the risk of terror but the cautionary words of Justice William Brennan28 of the United States Supreme Court in 1987 remain pertinent:

“There is considerably less to be proud about, and a good deal to be embarrassed about, when one reflects on the shabby treatment civil liberties have received in the United States during times of war and perceived threats to national security … After each perceived security crisis ended, the United States has remorsefully realized that the abrogation of civil liberties was unnecessary. But it has proven unable to prevent itself from repeating the error when the next crisis came along.”

“There is considerably less to be proud about, and a good deal to be embarrassed about, when one reflects on the shabby treatment civil liberties have received in the United States during times of war and perceived threats to national security … After each perceived security crisis ended, the United States has remorsefully realized that the abrogation of civil liberties was unnecessary. But it has proven unable to prevent itself from repeating the error when the next crisis came along.”

The legal profession has an important role in maintaining the rule of law, no less in times of danger as in times of peace. We remember the powerful proclamation of Lord Atkin in his celebrated dissent in Liversidge v Anderson29 written in one of the darkest periods of World War II:

“In this country, amid the clash of arms, the laws are not silent. They may be changed, but they speak the same language in war as in peace.”

The legal profession is a profession of service. In maintaining the rule of law, it gives vitality to the peace and order, the freedom and the decency, of the society in which we live. Sometimes that may be an anxious duty, sometimes difficult to perform. But that has long been the experience of a robust and proud profession.

The Hon Sir Gerard Brennan AC KBE

Discuss this article in the Hearsay Forum

Footnotes

- Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd (58) (1971) 17 FLR 141, 267.

- Australian Communist Party v. The Commonwealth (1951) 83 CLR 1, 193.

- Sixth Sir David Williams Lecture, Cambridge, 16 November 2006.

- See Tom Bingham, “Personal Freedom and the Dilemma of Democracies” (2003) 52 ICLQ 841.

- Introduction to the study of the law of the Constitution (10th ed, 1959) at 202-203.

- (1607) 12 Co Rep 63 at 64-65 [77] ER 1342 at 1343].

- (1803) 5 US (1 Cranch) 137, 177.

- [2005] 2 AC 68, [2004] UKHL 56, paras 42.

- “Government and the Rule of Law in the Modern Age” in the LSE Law Department and Clifford Chance Lecture series on Rule of Law 22 February 2006.

- See Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v The Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106.

- Dickason v Dickason (1913) 17 CLR 50, 51; [1913] HCA 77 per Barton ACJ for the Court.

- (1976) 134 CLR 495, 532 [1976] HCA 23 par 10.

- “Why Write Judgments?” (1992) 66 Australian Law Journal 787 at 790.

- See Devlin “Judges and Lawmakers” (1976) 39 Modern Law Review 1 at 4, reproduced in Devlin, The Judge (1979) at 4.

- R v Watson; Ex parte Armstrong (1976) 136 CLR 248.

- Australian Communist Party v The Commonwealth (1951) 83 CLR 1.

- (1992) 18 Melbourne University Law Review 630 at 658.

- The rule does not apply when, of necessity, a particular judge must sit on a case.

- Grassby v The Queen (1989) 168 CLR 1 at 20 per Dawson J. citing Livesey v New South Wales Bar Association (1983) 151 CLR 288 and Reg. v Watson; Ex parte Armstrong (1976) 136 CLR 248.

- (1992) 174 CLR 455, 470 per Mason CJ, Dawson and McHugh JJ.

- “Götterdammerung -gods of the law in decline” (1981) 1(1) Legal Studies 3, 13.

- Railway Express Agency Inc v New York 336 US 106, 112-113 (1949), cited by Lord Bingham.

- John Locke, Second Treatise of Government (1690), Chap XVII, s.202 (Cambridge University Press, 1988), quoted by Lord Bingham.

- A v Hayden (1984) 156 CLR 532; Ridgeway v The Queen (1995) 184 CLR 19.

- Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth of Australia (2003) 211 CLR 476, 513-514; [2003] HCA 2 and see Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs; Ex parte Applicant S20/2002 [2003] HCA 30; 77 ALJR 1165.

- Division 3.

- Part 5.3, Division 100.

- William J Brennan Jr, “The Quest to Develop a Jurisprudence of Civil Liberties in Times of Security Crises” 18 Israel Yearbook of Human Rights (1988) 11 cited by Lord Bingham in the Sixth Sir David Williams Lecture.

- Liversidge v Anderson [1942] AC 206, 245 at p.244.

The law regulates complex relationships — relationships between people and relationships between the people and the state. In a society governed by the rule of law, special knowledge and skills are needed to administer a “subtle and elaborate system”. Competence, as well as authority, was the concern of Lord Coke’s famous rejection in the case of Prohibitions Del Roy6 of King James I’s pretensions to judge:

The law regulates complex relationships — relationships between people and relationships between the people and the state. In a society governed by the rule of law, special knowledge and skills are needed to administer a “subtle and elaborate system”. Competence, as well as authority, was the concern of Lord Coke’s famous rejection in the case of Prohibitions Del Roy6 of King James I’s pretensions to judge: The declaration of the law is a basic, but not the only, element in the operation of the rule of law. Much depends on the terms in which the law is framed and on the manner in which it is applied. A literal application of laws which trample on basic human rights may be the very antithesis of the rule of law. Some of Hitler’s heinous policies were implemented in accordance with German law as it then was. There is a difference between the rule of law and rule by law. In a recent speech, the British Attorney-General, Lord Goldsmith QC, said that the rule of law —

The declaration of the law is a basic, but not the only, element in the operation of the rule of law. Much depends on the terms in which the law is framed and on the manner in which it is applied. A literal application of laws which trample on basic human rights may be the very antithesis of the rule of law. Some of Hitler’s heinous policies were implemented in accordance with German law as it then was. There is a difference between the rule of law and rule by law. In a recent speech, the British Attorney-General, Lord Goldsmith QC, said that the rule of law — A peaceful and ordered society needs the rule of law but it also needs to be secure against disruption from both external and internal sources. How are these two needs to be satisfied or, if not satisfied, reconciled; or, if not reconciled, balanced? Perhaps the answer is to be found in what it is that sustains the rule of law. Most lawyers are familiar with the danger created by ordinary criminal conduct and, over the years, the courts and the legislature have prescribed the steps to be taken in detecting and punishing crime and the procedures and penalties which are intended to suppress it. But lawyers generally do not know the true nature and extent of the threat posed by terrorism today and, like many others, are uncertain about the steps which should be taken to suppress it. What lawyers do know, however, is what laws, practices and procedures provide the safeguards which maintain public confidence in the rule of law. When the conventional safeguards of law and the legal process are dismantled or reduced so that the public sense that justice according to law is no longer assured to all people within the jurisdiction, public confidence in the rule of law is lost or diminished. That weakens the unity and fabric of society and exposes us to danger from those who do not share a respect for the rule of law.

A peaceful and ordered society needs the rule of law but it also needs to be secure against disruption from both external and internal sources. How are these two needs to be satisfied or, if not satisfied, reconciled; or, if not reconciled, balanced? Perhaps the answer is to be found in what it is that sustains the rule of law. Most lawyers are familiar with the danger created by ordinary criminal conduct and, over the years, the courts and the legislature have prescribed the steps to be taken in detecting and punishing crime and the procedures and penalties which are intended to suppress it. But lawyers generally do not know the true nature and extent of the threat posed by terrorism today and, like many others, are uncertain about the steps which should be taken to suppress it. What lawyers do know, however, is what laws, practices and procedures provide the safeguards which maintain public confidence in the rule of law. When the conventional safeguards of law and the legal process are dismantled or reduced so that the public sense that justice according to law is no longer assured to all people within the jurisdiction, public confidence in the rule of law is lost or diminished. That weakens the unity and fabric of society and exposes us to danger from those who do not share a respect for the rule of law. “There is considerably less to be proud about, and a good deal to be embarrassed about, when one reflects on the shabby treatment civil liberties have received in the United States during times of war and perceived threats to national security … After each perceived security crisis ended, the United States has remorsefully realized that the abrogation of civil liberties was unnecessary. But it has proven unable to prevent itself from repeating the error when the next crisis came along.”

“There is considerably less to be proud about, and a good deal to be embarrassed about, when one reflects on the shabby treatment civil liberties have received in the United States during times of war and perceived threats to national security … After each perceived security crisis ended, the United States has remorsefully realized that the abrogation of civil liberties was unnecessary. But it has proven unable to prevent itself from repeating the error when the next crisis came along.”