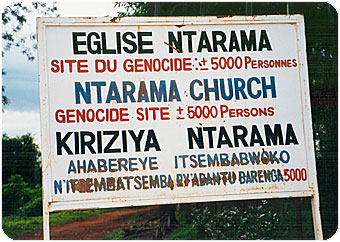

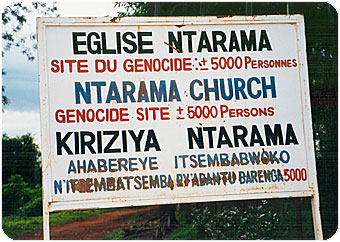

The place is Ntarama. It is a small region south of Kigali, just by what is now the Nelson Mandela Peace Village. But nothing can prepare you for the visually sickening horror that confronts and offends and finally chokes you.

The place is Ntarama. It is a small region south of Kigali, just by what is now the Nelson Mandela Peace Village. But nothing can prepare you for the visually sickening horror that confronts and offends and finally chokes you.

You leave the centre of Kigali and climb a long hill. The road from Kigali is bitumen and is crowded with the business of the day. Vans and trucks are overloaded belching grey and black fumes, a tribute to diesel injectors well overdue for maintenance. But then the rest of the vehicle is as well. The battered rusting hulks are both an analogy, and life blood, of a nation. Life is about getting there and making a living for today; it is ensuring that, tonight, there will be a fire upon which to cook some food.

Bags and bags of charcoal stand in rows waiting for consumers. Consumers of the forests of Rwanda. But there is food. Rwanda is a fertile country, volcanic in origin, with rich red volcanic soil of immense depth. So food is available in many small stalls and shops. Survival demands that there must be a way to make a living and this is one such way. A few pieces of timber, some old galvanised iron, an old sheet of plastic, or even a UN tarpaulin will do. The shop, the stall and the shanty are all open for business. They squeeze every last centimetre of the frontage to the streets as I start to climb out of Kigali, not far from the headquarters of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, in Rwanda.

Bags and bags of charcoal stand in rows waiting for consumers. Consumers of the forests of Rwanda. But there is food. Rwanda is a fertile country, volcanic in origin, with rich red volcanic soil of immense depth. So food is available in many small stalls and shops. Survival demands that there must be a way to make a living and this is one such way. A few pieces of timber, some old galvanised iron, an old sheet of plastic, or even a UN tarpaulin will do. The shop, the stall and the shanty are all open for business. They squeeze every last centimetre of the frontage to the streets as I start to climb out of Kigali, not far from the headquarters of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, in Rwanda.

There is no common architecture, but the permanent buildings mainly are of handmade concrete blocks. The most notable feature of most buildings is the protruding rusting reinforcing, awaiting available funds for the next row of blocks or concrete mix. Every habitable space inside the buildings is taken up, whether buildings are complete or not, and families sit in the dark shade away from the increasing intensity of an equatorial sun.

The road continues to climb but no longer is it a bitumen surface. There are potholes and dust. Choking yellow dust. The stalls still lining the road clean the best they can, but a layer of dust remains. There are pedestrians, thousands of pedestrians, because this is both a cheap and reliable way of travel. Life does not require much travel anymore in Rwanda. The days of flight are over, at least for the time being. Life takes on a pattern of survival, trade and commerce to ensure that today we eat. With that goes the aggressive marketing, the importuning, to extract from me sufficient to buy a meal in exchange for something that I must have. As uncomfortable as it is, who can blame the marketer?

But the mask is there; that blanket over a collective consciousness. The individual emotionless faces are etched by the brutality of one of the most heinous crimes of the 20th Century. Every family will be affected. If they have not lost at least one member to the genocide there will be an emotional or physical cripple to care for, or there will be a member held in prison to account for their part in this immense, stupefying crime. And the war orphans on the streets!

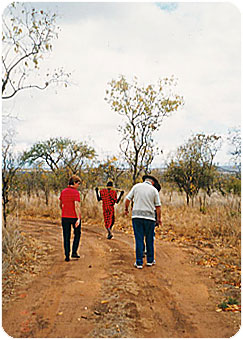

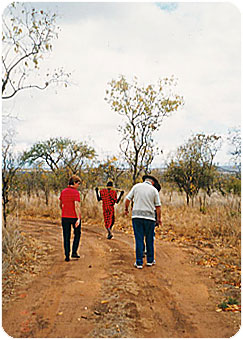

I continue the climb and the city gives way to a bush and rock strewn hill, which is unlike most of Rwanda. There is no vegetation edible to man or beast on this hill, and no intensive farming. It is the dry season, but the area seems to be particularly dry. Just the charcoal burners, they too making a living in the aftermath of a bloody era, and removing what stunted growth remains. The mounds of damp earth leaking smoke identify the locations of these endeavours.

I reached the top, bone jarred, but cocooned in air-conditioned comfort. I descend to a fertile region and there, on the right, are markets. Open air in the main including the barbers doing a roaring trade. Short, back and sides is definitely fashionable. In fact, I suspect they are all number one blades, and even then some are shaven. Handsome with shoulders square facing the world. And colour. Vibrant colour in fabric, especially for women.

Up again and down again, but this time to a broad valley through which is flowing a brown river, surprisingly fast and full. But it is a narrow road and as I take the final left curve to line up with the causeway and the bridge, it is easy to picture the roadblocks of 1994. At that point there was no escape. There was only the prospect of moving forward to something unknown. On each side of a causeway leading out to the centre of the river is marshland planted with grasses to feed cattle and sugarcane of indefinite shape and length. The causeway leads to the main channel and it is there that the bridge spans the Nyabarongo River. This river and its tributaries drain the marshlands of the river valley and it finally makes it way into the Nile System. This was the river which was delivering, as promised, corpses back to Tutsi homelands by their thousands. As Dr Leon Mugersera said on 22 November, 1992, 17 months prior to the genocide:

Up again and down again, but this time to a broad valley through which is flowing a brown river, surprisingly fast and full. But it is a narrow road and as I take the final left curve to line up with the causeway and the bridge, it is easy to picture the roadblocks of 1994. At that point there was no escape. There was only the prospect of moving forward to something unknown. On each side of a causeway leading out to the centre of the river is marshland planted with grasses to feed cattle and sugarcane of indefinite shape and length. The causeway leads to the main channel and it is there that the bridge spans the Nyabarongo River. This river and its tributaries drain the marshlands of the river valley and it finally makes it way into the Nile System. This was the river which was delivering, as promised, corpses back to Tutsi homelands by their thousands. As Dr Leon Mugersera said on 22 November, 1992, 17 months prior to the genocide:

“You cell members, work together watch out for intruders in your cell, suppress them. Do anything you can so that no body sneaks out. The fatal mistake we made in 1959 is that we let them (tutsi) out of the country. Their homeland is Ethiopia, we will cut their throats and sent them to Ethiopia through the short-cut, that is, river Nyabyarongo.”

But you would not imagine it today, given the peace that is apparent and palpable, and the commerce and daily business of the people.

But I can make it to the other side without hindrance, threat or obstacle and I continue to drive south, up another hill, through the dust and the potholes, and then emerge more or less on a plateau. Here now there are no soldiers, police or militia, leading a rabble of civilians armed with whatever weapon comes to hand and can kill. But the descriptions are etched upon the mind and imagination. This is fertile ground and life is slower than the city. This is the place where people wait for the seasons, which are fairly reliable in this part of the world, and the cycle of life bears fruit in its season. There is enough to eat, and even to sell. At the moment though, it is dry and the soil is tilled by hand, awaiting the first rain. This is the time for patience and reflection, and long conversations.

I drive further and come to the fork in the road heading to the Nelson Mandela Peace Village, a project named after a man of peace, built with an optimism in respect of the future of Rwanda, but more importantly an optimism in respect of human behaviour. That optimism must not be misplaced, just because, a few kilometres further on, is Ntarama. The legend on the map tells me that there is a church or mission at Ntarama. That is my destination, along a side road servicing only a few farms with mostly cattle. There is a place of tranquillity. And the Eucalyptus trees! That is another story of colonial invasion and railway lines. They grow so prolifically in this very beautiful climate and become a feature of the landscape. The Eucalypts have taken over here and formed front and side boundaries to this property. There is now a fence, chain wire, with a gate. Not that that would have done any good at the time. There is a walkway in the shade of the trees, shadows being cast by a slanting sun. There is a caretaker who sits in an alcove in a galvanised iron shed. This shed is next to the church. The church is a rectangular red brick building with a metal roof. It is about 10 metres wide by about 30 metres in length. But there are features which should not be there. There are holes in the walls; bricks smashed out. On the side of the church farthest from the road there are more holes, and behind that are skillion-roofed sheds. There is no rush here, and there is a silence, which is appealing. But then why wouldn’t it be appealing? Gone are the terrors, the screams, the grenades exploding, the guns firing and the sound, the dull sound, of clubbing.

I drive further and come to the fork in the road heading to the Nelson Mandela Peace Village, a project named after a man of peace, built with an optimism in respect of the future of Rwanda, but more importantly an optimism in respect of human behaviour. That optimism must not be misplaced, just because, a few kilometres further on, is Ntarama. The legend on the map tells me that there is a church or mission at Ntarama. That is my destination, along a side road servicing only a few farms with mostly cattle. There is a place of tranquillity. And the Eucalyptus trees! That is another story of colonial invasion and railway lines. They grow so prolifically in this very beautiful climate and become a feature of the landscape. The Eucalypts have taken over here and formed front and side boundaries to this property. There is now a fence, chain wire, with a gate. Not that that would have done any good at the time. There is a walkway in the shade of the trees, shadows being cast by a slanting sun. There is a caretaker who sits in an alcove in a galvanised iron shed. This shed is next to the church. The church is a rectangular red brick building with a metal roof. It is about 10 metres wide by about 30 metres in length. But there are features which should not be there. There are holes in the walls; bricks smashed out. On the side of the church farthest from the road there are more holes, and behind that are skillion-roofed sheds. There is no rush here, and there is a silence, which is appealing. But then why wouldn’t it be appealing? Gone are the terrors, the screams, the grenades exploding, the guns firing and the sound, the dull sound, of clubbing.

The church is empty. Empty? I mean there is no living creature in the church, neither human nor animal. There is instead a putrescent mass 15 centimetres deep across the floor. Nothing has changed from that day in April 1994, except the continuing decay of what was. Perhaps the skulls have been plucked from rotting flesh and membrane, but the human skeletons and the degenerating clothes they wore on the fatal day remain. The pews are low, narrow and backless. This was not a society given to excesses or extremes, but one where those of a Christian faith came together in simplicity, without demonstration of anything but individual and personal faith, and there they died. The churches were a place of sanctuary, and, in one of the most cynical exercises of the ravaging of the heart and soul of the people, the call went out to come to a sanctuary such as this, and there you will find protection. And so the people came with meagre possessions, helping their aged and their infants, unarmed and defenceless, to the building where there were few windows and one door. How many thousands of people were there is difficult to know. But the walls were breached and holes created for grenades to be thrown in, and the rifles to be fired, and so a carnage began.

Those who did not die quickly were slaughtered by hand when the enemy entered the sanctuary. Precious simple possessions were mixed with bibles and hymnals and the church became a sea of screaming, pleas for mercy on the one hand, and for blood on the other. The blood satiated everything including, it would seem, the killers. The blood mixed with the bibles and the hymnals, and the simple possessions, and the bodies of the old men and women, and the mothers and young women and the children. And there they died in the sanctuary.

And there they remain, slowly and inevitably rotting away, the silent reminder of this 20th Century massacre. Among the clothes are the bones. The bones left as the brutal memorial as this site is, to the carnage and hatred that once existed in this place. It is beyond description, spreading from wall-to-wall, from nave to altar, without discrimination, and now without form or identity. The oneness of humanity; the dust to dust; the nakedness of birth and death; the decay of morality.

And there they remain, slowly and inevitably rotting away, the silent reminder of this 20th Century massacre. Among the clothes are the bones. The bones left as the brutal memorial as this site is, to the carnage and hatred that once existed in this place. It is beyond description, spreading from wall-to-wall, from nave to altar, without discrimination, and now without form or identity. The oneness of humanity; the dust to dust; the nakedness of birth and death; the decay of morality.

On the wall of the entrance to the church is still, faded and tattered with marks all over it, a poster, written in French. 1994 was the International Year of the Woman. The poster commemorates the struggle for recognition of womanhood and tells me that in March of 1994 there was a celebration of that fact within that church. The bones are the ultimate denial of recognition of womanhood and the testament to the inhumanity of man to womanhood. Able men were off doing things. The women, the children and the old men sought refuge in the church. And there they paid with their lives.

There are out buildings as well. Simple buildings of corrugated galvanised iron and mud walls. Buildings used for Christian education, the process of illuminating small groups. There remain small groups in those buildings, small groups of bones of those desperately hiding for their lives, but found and murdered. I go to the partly completed brick building at the end of the church. And there are bags of bones. What can you do if you have too many bones? I suppose you can only put them into maize sacks and store them in available buildings and corners.

There are out buildings as well. Simple buildings of corrugated galvanised iron and mud walls. Buildings used for Christian education, the process of illuminating small groups. There remain small groups in those buildings, small groups of bones of those desperately hiding for their lives, but found and murdered. I go to the partly completed brick building at the end of the church. And there are bags of bones. What can you do if you have too many bones? I suppose you can only put them into maize sacks and store them in available buildings and corners.

Then there is the more substantial building. I am not sure for what purpose that building was used. It was brick and solid, but with no door. Inside was the vision incomprehensible. More bones. Hessian bag after hessian bag filled with bones. For what reason? Awaiting burial? Awaiting assembly in some further tribute to the brutal, macabre energy of what was? Or awaiting the knitting together, a resurrection, some symbol of union or hope, or future?

And then I come to the building that I know houses something, because I am encouraged to look inside. But what can prepare anyone for this? About 1.5 metres from the floor is a rack, occupying the whole of this building except for a walkway down one side. And on that shelf are skulls, skulls, and more skulls, line after line of life extinct. There is not enough room and some have fallen off. There are small skulls and there are large skulls. There are skulls with no apparent sign of violence and there are skulls with bullet holes in them. There are skulls with long gashes through the bone. There are skulls that have simply been whacked and are caved in. There are skulls with irregular jagged holes, victims of the lumps of timber with long nails driven through them. There are skulls with metal still protruding from them. There are eye sockets, thousands of them, all facing the door. There are maybe 2,000 skulls lined up as though on military parade, dressing from the left. The waste, the immense unnecessary tragic waste. The memorial to stupidity, politics, wealth, power and intransigence. A tribute to the lack of sight or action of the world. There are none so blind as those who refuse to see! Nor those so culpable as those who refuse to act!

And then I come to the building that I know houses something, because I am encouraged to look inside. But what can prepare anyone for this? About 1.5 metres from the floor is a rack, occupying the whole of this building except for a walkway down one side. And on that shelf are skulls, skulls, and more skulls, line after line of life extinct. There is not enough room and some have fallen off. There are small skulls and there are large skulls. There are skulls with no apparent sign of violence and there are skulls with bullet holes in them. There are skulls with long gashes through the bone. There are skulls that have simply been whacked and are caved in. There are skulls with irregular jagged holes, victims of the lumps of timber with long nails driven through them. There are skulls with metal still protruding from them. There are eye sockets, thousands of them, all facing the door. There are maybe 2,000 skulls lined up as though on military parade, dressing from the left. The waste, the immense unnecessary tragic waste. The memorial to stupidity, politics, wealth, power and intransigence. A tribute to the lack of sight or action of the world. There are none so blind as those who refuse to see! Nor those so culpable as those who refuse to act!

The aquiline noses have gone and all that remains is the cleft where once a nose was. The high cheekbones are visible. But it is the teeth that drag your attention down. The teeth tell the story of a people and their massacre. There are large skulls with few, or no, teeth. The aged who have lived their full life until now are dead, not because they deserve to die; not because they have made no contribution to the welfare of their community; not because they are not revered or loved in their community; but purely because they were Tutsi. Then, at the other end of the scale, there are the small skulls, there are the tiny skulls, some with no teeth, some with a few front teeth, and some with a small set of teeth. The infants, the innocents, not because of over population, not for spiritual sacrifice, not because they are unwanted by their community and their families, but because they are, or suspected to be, Tutsi. And then there are the skulls, obviously of females. They are delicate, with well preserved teeth, teeth of young people who are perhaps mothers or who have learnt to take care of themselves in a world which has been kind to them, a world where, perhaps, they were courted by young men of a different ethnic grouping or a different village, or a world in which their husband was a good man, either a Tutsi or a Hutu. But they are dead, not because they are not good mothers, not because they have not cared and provided for their children and family, not because they would not make good mothers, but just because they are Tutsi. And in the bitterest irony, on the back wall of the church was the poster dedicated to the International Year of the Woman, celebrated on a Sunday only one month before.

The aquiline noses have gone and all that remains is the cleft where once a nose was. The high cheekbones are visible. But it is the teeth that drag your attention down. The teeth tell the story of a people and their massacre. There are large skulls with few, or no, teeth. The aged who have lived their full life until now are dead, not because they deserve to die; not because they have made no contribution to the welfare of their community; not because they are not revered or loved in their community; but purely because they were Tutsi. Then, at the other end of the scale, there are the small skulls, there are the tiny skulls, some with no teeth, some with a few front teeth, and some with a small set of teeth. The infants, the innocents, not because of over population, not for spiritual sacrifice, not because they are unwanted by their community and their families, but because they are, or suspected to be, Tutsi. And then there are the skulls, obviously of females. They are delicate, with well preserved teeth, teeth of young people who are perhaps mothers or who have learnt to take care of themselves in a world which has been kind to them, a world where, perhaps, they were courted by young men of a different ethnic grouping or a different village, or a world in which their husband was a good man, either a Tutsi or a Hutu. But they are dead, not because they are not good mothers, not because they have not cared and provided for their children and family, not because they would not make good mothers, but just because they are Tutsi. And in the bitterest irony, on the back wall of the church was the poster dedicated to the International Year of the Woman, celebrated on a Sunday only one month before.

The afternoon sun slants through the Eucalypts surrounding the site, and through holes in the western wall of this skillion roofed structure, hastily built to house the starkest evidence of inhumanity, brutality, even barbarism. The sun casts eerie shadows punctuated by sharp light on skull, the contrast of the source and continuum of life and the untimely, unnecessary and bloody death of hundreds of thousands of people.

“But why did you kill the women and the children?” I asked witness after witness called in defence of the Minister for Information, Niyitegeka. “Because that is what happens in war” said witness after witness called to justify the perverse excesses of a hundred days. “But surely the women and the children were not participating in the war?” I asked the same question to witness after witness. “But the families belonged to the enemy and they had to die” came a couple of responses.

And the corrugated galvanised iron doors were drawn shut on this macabre arrangement, this virtuoso performance of death.

There are many other churches, many other mosques, schools, hospitals, public buildings and open spaces which saw the same senseless, needless, heedless, brutality. There are hundreds of sites of mass burials, and there are so many skeletons and bones that saw no burial, but were dismembered by the foraging of wild animals.

There are truths so central to human existence that these bones reverberate with more life than any sermon, homily, lesson, political manifesto or diatribe. And it reminds me that I am privileged to live in a society that embraces the rule of law.

Ken Fleming QC

T.J. Ryan Chambers

The place is Ntarama. It is a small region south of Kigali, just by what is now the Nelson Mandela Peace Village. But nothing can prepare you for the visually sickening horror that confronts and offends and finally chokes you.

The place is Ntarama. It is a small region south of Kigali, just by what is now the Nelson Mandela Peace Village. But nothing can prepare you for the visually sickening horror that confronts and offends and finally chokes you. Bags and bags of charcoal stand in rows waiting for consumers. Consumers of the forests of Rwanda. But there is food. Rwanda is a fertile country, volcanic in origin, with rich red volcanic soil of immense depth. So food is available in many small stalls and shops. Survival demands that there must be a way to make a living and this is one such way. A few pieces of timber, some old galvanised iron, an old sheet of plastic, or even a UN tarpaulin will do. The shop, the stall and the shanty are all open for business. They squeeze every last centimetre of the frontage to the streets as I start to climb out of Kigali, not far from the headquarters of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, in Rwanda.

Bags and bags of charcoal stand in rows waiting for consumers. Consumers of the forests of Rwanda. But there is food. Rwanda is a fertile country, volcanic in origin, with rich red volcanic soil of immense depth. So food is available in many small stalls and shops. Survival demands that there must be a way to make a living and this is one such way. A few pieces of timber, some old galvanised iron, an old sheet of plastic, or even a UN tarpaulin will do. The shop, the stall and the shanty are all open for business. They squeeze every last centimetre of the frontage to the streets as I start to climb out of Kigali, not far from the headquarters of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, in Rwanda. Up again and down again, but this time to a broad valley through which is flowing a brown river, surprisingly fast and full. But it is a narrow road and as I take the final left curve to line up with the causeway and the bridge, it is easy to picture the roadblocks of 1994. At that point there was no escape. There was only the prospect of moving forward to something unknown. On each side of a causeway leading out to the centre of the river is marshland planted with grasses to feed cattle and sugarcane of indefinite shape and length. The causeway leads to the main channel and it is there that the bridge spans the Nyabarongo River. This river and its tributaries drain the marshlands of the river valley and it finally makes it way into the Nile System. This was the river which was delivering, as promised, corpses back to Tutsi homelands by their thousands. As Dr Leon Mugersera said on 22 November, 1992, 17 months prior to the genocide:

Up again and down again, but this time to a broad valley through which is flowing a brown river, surprisingly fast and full. But it is a narrow road and as I take the final left curve to line up with the causeway and the bridge, it is easy to picture the roadblocks of 1994. At that point there was no escape. There was only the prospect of moving forward to something unknown. On each side of a causeway leading out to the centre of the river is marshland planted with grasses to feed cattle and sugarcane of indefinite shape and length. The causeway leads to the main channel and it is there that the bridge spans the Nyabarongo River. This river and its tributaries drain the marshlands of the river valley and it finally makes it way into the Nile System. This was the river which was delivering, as promised, corpses back to Tutsi homelands by their thousands. As Dr Leon Mugersera said on 22 November, 1992, 17 months prior to the genocide: I drive further and come to the fork in the road heading to the Nelson Mandela Peace Village, a project named after a man of peace, built with an optimism in respect of the future of Rwanda, but more importantly an optimism in respect of human behaviour. That optimism must not be misplaced, just because, a few kilometres further on, is Ntarama. The legend on the map tells me that there is a church or mission at Ntarama. That is my destination, along a side road servicing only a few farms with mostly cattle. There is a place of tranquillity. And the Eucalyptus trees! That is another story of colonial invasion and railway lines. They grow so prolifically in this very beautiful climate and become a feature of the landscape. The Eucalypts have taken over here and formed front and side boundaries to this property. There is now a fence, chain wire, with a gate. Not that that would have done any good at the time. There is a walkway in the shade of the trees, shadows being cast by a slanting sun. There is a caretaker who sits in an alcove in a galvanised iron shed. This shed is next to the church. The church is a rectangular red brick building with a metal roof. It is about 10 metres wide by about 30 metres in length. But there are features which should not be there. There are holes in the walls; bricks smashed out. On the side of the church farthest from the road there are more holes, and behind that are skillion-roofed sheds. There is no rush here, and there is a silence, which is appealing. But then why wouldn’t it be appealing? Gone are the terrors, the screams, the grenades exploding, the guns firing and the sound, the dull sound, of clubbing.

I drive further and come to the fork in the road heading to the Nelson Mandela Peace Village, a project named after a man of peace, built with an optimism in respect of the future of Rwanda, but more importantly an optimism in respect of human behaviour. That optimism must not be misplaced, just because, a few kilometres further on, is Ntarama. The legend on the map tells me that there is a church or mission at Ntarama. That is my destination, along a side road servicing only a few farms with mostly cattle. There is a place of tranquillity. And the Eucalyptus trees! That is another story of colonial invasion and railway lines. They grow so prolifically in this very beautiful climate and become a feature of the landscape. The Eucalypts have taken over here and formed front and side boundaries to this property. There is now a fence, chain wire, with a gate. Not that that would have done any good at the time. There is a walkway in the shade of the trees, shadows being cast by a slanting sun. There is a caretaker who sits in an alcove in a galvanised iron shed. This shed is next to the church. The church is a rectangular red brick building with a metal roof. It is about 10 metres wide by about 30 metres in length. But there are features which should not be there. There are holes in the walls; bricks smashed out. On the side of the church farthest from the road there are more holes, and behind that are skillion-roofed sheds. There is no rush here, and there is a silence, which is appealing. But then why wouldn’t it be appealing? Gone are the terrors, the screams, the grenades exploding, the guns firing and the sound, the dull sound, of clubbing. And there they remain, slowly and inevitably rotting away, the silent reminder of this 20th Century massacre. Among the clothes are the bones. The bones left as the brutal memorial as this site is, to the carnage and hatred that once existed in this place. It is beyond description, spreading from wall-to-wall, from nave to altar, without discrimination, and now without form or identity. The oneness of humanity; the dust to dust; the nakedness of birth and death; the decay of morality.

And there they remain, slowly and inevitably rotting away, the silent reminder of this 20th Century massacre. Among the clothes are the bones. The bones left as the brutal memorial as this site is, to the carnage and hatred that once existed in this place. It is beyond description, spreading from wall-to-wall, from nave to altar, without discrimination, and now without form or identity. The oneness of humanity; the dust to dust; the nakedness of birth and death; the decay of morality. There are out buildings as well. Simple buildings of corrugated galvanised iron and mud walls. Buildings used for Christian education, the process of illuminating small groups. There remain small groups in those buildings, small groups of bones of those desperately hiding for their lives, but found and murdered. I go to the partly completed brick building at the end of the church. And there are bags of bones. What can you do if you have too many bones? I suppose you can only put them into maize sacks and store them in available buildings and corners.

There are out buildings as well. Simple buildings of corrugated galvanised iron and mud walls. Buildings used for Christian education, the process of illuminating small groups. There remain small groups in those buildings, small groups of bones of those desperately hiding for their lives, but found and murdered. I go to the partly completed brick building at the end of the church. And there are bags of bones. What can you do if you have too many bones? I suppose you can only put them into maize sacks and store them in available buildings and corners. And then I come to the building that I know houses something, because I am encouraged to look inside. But what can prepare anyone for this? About 1.5 metres from the floor is a rack, occupying the whole of this building except for a walkway down one side. And on that shelf are skulls, skulls, and more skulls, line after line of life extinct. There is not enough room and some have fallen off. There are small skulls and there are large skulls. There are skulls with no apparent sign of violence and there are skulls with bullet holes in them. There are skulls with long gashes through the bone. There are skulls that have simply been whacked and are caved in. There are skulls with irregular jagged holes, victims of the lumps of timber with long nails driven through them. There are skulls with metal still protruding from them. There are eye sockets, thousands of them, all facing the door. There are maybe 2,000 skulls lined up as though on military parade, dressing from the left. The waste, the immense unnecessary tragic waste. The memorial to stupidity, politics, wealth, power and intransigence. A tribute to the lack of sight or action of the world. There are none so blind as those who refuse to see! Nor those so culpable as those who refuse to act!

And then I come to the building that I know houses something, because I am encouraged to look inside. But what can prepare anyone for this? About 1.5 metres from the floor is a rack, occupying the whole of this building except for a walkway down one side. And on that shelf are skulls, skulls, and more skulls, line after line of life extinct. There is not enough room and some have fallen off. There are small skulls and there are large skulls. There are skulls with no apparent sign of violence and there are skulls with bullet holes in them. There are skulls with long gashes through the bone. There are skulls that have simply been whacked and are caved in. There are skulls with irregular jagged holes, victims of the lumps of timber with long nails driven through them. There are skulls with metal still protruding from them. There are eye sockets, thousands of them, all facing the door. There are maybe 2,000 skulls lined up as though on military parade, dressing from the left. The waste, the immense unnecessary tragic waste. The memorial to stupidity, politics, wealth, power and intransigence. A tribute to the lack of sight or action of the world. There are none so blind as those who refuse to see! Nor those so culpable as those who refuse to act! The aquiline noses have gone and all that remains is the cleft where once a nose was. The high cheekbones are visible. But it is the teeth that drag your attention down. The teeth tell the story of a people and their massacre. There are large skulls with few, or no, teeth. The aged who have lived their full life until now are dead, not because they deserve to die; not because they have made no contribution to the welfare of their community; not because they are not revered or loved in their community; but purely because they were Tutsi. Then, at the other end of the scale, there are the small skulls, there are the tiny skulls, some with no teeth, some with a few front teeth, and some with a small set of teeth. The infants, the innocents, not because of over population, not for spiritual sacrifice, not because they are unwanted by their community and their families, but because they are, or suspected to be, Tutsi. And then there are the skulls, obviously of females. They are delicate, with well preserved teeth, teeth of young people who are perhaps mothers or who have learnt to take care of themselves in a world which has been kind to them, a world where, perhaps, they were courted by young men of a different ethnic grouping or a different village, or a world in which their husband was a good man, either a Tutsi or a Hutu. But they are dead, not because they are not good mothers, not because they have not cared and provided for their children and family, not because they would not make good mothers, but just because they are Tutsi. And in the bitterest irony, on the back wall of the church was the poster dedicated to the International Year of the Woman, celebrated on a Sunday only one month before.

The aquiline noses have gone and all that remains is the cleft where once a nose was. The high cheekbones are visible. But it is the teeth that drag your attention down. The teeth tell the story of a people and their massacre. There are large skulls with few, or no, teeth. The aged who have lived their full life until now are dead, not because they deserve to die; not because they have made no contribution to the welfare of their community; not because they are not revered or loved in their community; but purely because they were Tutsi. Then, at the other end of the scale, there are the small skulls, there are the tiny skulls, some with no teeth, some with a few front teeth, and some with a small set of teeth. The infants, the innocents, not because of over population, not for spiritual sacrifice, not because they are unwanted by their community and their families, but because they are, or suspected to be, Tutsi. And then there are the skulls, obviously of females. They are delicate, with well preserved teeth, teeth of young people who are perhaps mothers or who have learnt to take care of themselves in a world which has been kind to them, a world where, perhaps, they were courted by young men of a different ethnic grouping or a different village, or a world in which their husband was a good man, either a Tutsi or a Hutu. But they are dead, not because they are not good mothers, not because they have not cared and provided for their children and family, not because they would not make good mothers, but just because they are Tutsi. And in the bitterest irony, on the back wall of the church was the poster dedicated to the International Year of the Woman, celebrated on a Sunday only one month before.