Bangladesh is a country of many challenges and difficulties. It is a country where the poverty is abject, where, over 8 million children, from about 5 or 6 years of age, must work to either support themselves or supplement a meagre family income. Typically, these children work as domestic servants, hawkers, brick breakers, rag pickers or day labourers.

Workplace health and safety is an indulgence not afforded them. Sitting in a class room to receive an education is a luxury which simply cannot compete with the immediate need to earn a miniscule sum of money for the most basic of food and shelter.

Thus, poverty and its bedfellow illiteracy, another significant problem in Bangladesh, create a vicious, generational cycle of poor, illiterate parents, whose children must therefore work. In turn, those children become impoverished, uneducated adults and then poor, illiterate parents. The cycle continues.

But education can be the game changer. As Nelson Mandela said: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

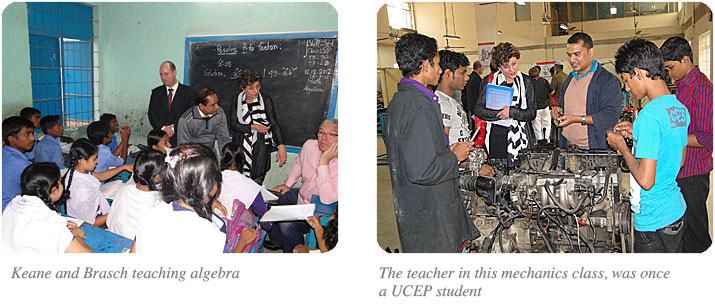

You all no doubt remember the letters sent to you each year by Dan O’Gorman SC requesting donations for the UCEP Schools. Those of you who recently donated will be receiving pictures and short biographies of the children your donations have helped. Brasch and (Peachy) Keane recently saw first-hand those schools and those children who would otherwise remain largely illiterate and certainly living well below that country’s poverty line.

You all no doubt remember the letters sent to you each year by Dan O’Gorman SC requesting donations for the UCEP Schools. Those of you who recently donated will be receiving pictures and short biographies of the children your donations have helped. Brasch and (Peachy) Keane recently saw first-hand those schools and those children who would otherwise remain largely illiterate and certainly living well below that country’s poverty line.

As much as we:

- enjoyed the delights of down town Dhaka (where all road rules are optional and temporary, but we couldn’t enter our hotel without bomb tests on our car);

- had a ball with O’Gorman in otherwise dry-Dhaka when he received the phone call that his daughter (and our colleague) Kateena had safely delivered her and Zim’s daughter, and thus Dan & Madeline’s granddaughter (he discovered a single bottle of Moet costs more than AUD$450 in Dhaka);

- were mesmerized watching men skin chickens in the median strip of a busy highway (most of us ate vegetarian from thereon in);

- managed to converse with our Victorian colleagues (despite their incessant chatter about AFL and equally strange gym attire);

- enjoyed teaching the advocacy courses at the Bar Council of Bangladesh (the actual point of our trip);

without a doubt, the singular highlight of our journey was our visit to two of the UCEP School’s in Dhaka.

There, in two UCEP schools in an urban slum — “slum” being their title (imagine a ghetto without hygiene or ethnic diversity) – we met hundreds of students, all of whom proudly called themselves “Child Workers”. We soon learned however that to be a flower seller or fruit seller or ice cream seller was to run between cars on congested roads, thick with smog, knocking on windows to hawk their wares. We also learned that to be a factory worker involved, perhaps at 6 years old, welding without any protective equipment, or, pouring acids, again without any protection, from one decomposing plastic bottle to a smaller one. But they were all proud that they were workers.

Yet, they seemed even prouder to be at school, to be learning and to be wearing a uniform. No matter how destitute the child, every student had a clean and beautifully pressed uniform, which they all seemed to wear as a badge of honour. Perhaps, they understood that the uniform was a tangible symbol representing a path out of the slums; their path to a life not likely to be of great wealth and privilege, but a ticket to hope. Both schools were as clean and tidy as any place we visited in Dhaka.

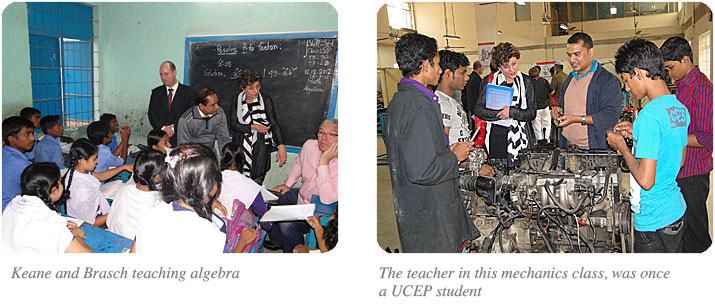

The 53 UCEP primary schools throughout Bangladesh run on a very clever model. The children only attend 3.5 hours a day, meaning they can still work. They must buy the material for their uniform (50 Taka = AUD$0.60) which therefore demonstrates commitment to the Program. They, or their parents, are required to make the uniform. The schools are all built in the urban slums, where the target group of child workers live, meaning they can walk there. They do grades 1 -8 in 4 years, again reducing the competition with work. Upon completion of primary school they can complete a 6 month bridging course and then learn a trade at one of the UCEP Vocational Colleges, which takes 1.5 years to complete.

Every student, upon the completion of each grade of school and College is given 400 Taka ($4.78) as’ compensation for the income they have forgone while at school. Then, perhaps most importantly, the school has a job placement program with a success rate of 96% of students placed in a job, for which they have trained, within 6 months.

As another perspective, in a country where many of the male population seem to place women as far, far less than equal, and where illiteracy amongst women is even worse than men, the school requires a 50-50 gender spread enrolment. Of the students at the UCEP School we visited, 63 young girls attended the school because they had been sent to Dhaka for “Migration for Marriage”; they were 10-14 years old. We don’t know how they ended up at the school. All we know is 63 young girls are enrolled at this school who were sent to Dhaka to be married at such a tender age. We doubt though that they would have been at the school if also married.

The other causes for entrance into the school as underprivileged, be it male or female, included: economic hardship; homeless; landless; river erosion; looking for work; and, family conflict. More than 20% of the students earned less than 11 Taka a day (AUD 13 cents). Sixty percent earned between 11 Taka to 25 Taka a day (AUD 30 cents). Twenty per cent lived under a tin shed wall, another 20% lived in tin sheds, whilst a little less than 10% specified their housing to be “a bamboo mat.”

The other causes for entrance into the school as underprivileged, be it male or female, included: economic hardship; homeless; landless; river erosion; looking for work; and, family conflict. More than 20% of the students earned less than 11 Taka a day (AUD 13 cents). Sixty percent earned between 11 Taka to 25 Taka a day (AUD 30 cents). Twenty per cent lived under a tin shed wall, another 20% lived in tin sheds, whilst a little less than 10% specified their housing to be “a bamboo mat.”

The ray of hope though is that the children, once through the school and College, will increase their income by an average of 450% and perhaps more powerfully, are literate in both Bangla and English as well as computer skills, and their chosen vocation. The Schools which we visited in Mirpur were English medium schools (that is all the classes were in English). Frankly the level of fluency of these children put some of our Advocacy Course students to shame (to put that in perspective all superior Bangladeshi Courts are conducted in English —a legacy of the colonial history our nations share).

As marvellous as this school program is, it is sobering to then understand that:

At present UCEP is addressing about 0.56 percent (45,000) of the total working children. Most of these unfortunate children are employed in the sectors earmarked as hazardous for children by the International Labor Organization.1

Do the maths — if UCEP reaches only 0.56% of working children, then, there are over 8 Million child labourers in Bangladesh working in ill-paid and hazardous jobs. Through the efforts of Dan O’Gorman SC, our Bar Association is a small but significant supporter of UCEP. We contribute as an association approximately $30,000 USD each year. This is something to be proud of, however to expand the UCEP program each new school costs $250,000 AUD. This should be our target in the years to come.

For us, one young lady summed up all that is the value of every dollar we, Queensland Barristers, individually donate to this school. After telling us her mother lived in an island village many miles away from Dhaka, that her father was “estranged to us”, that her brothers lived somewhere else in Dhaka, and that she lived at an NGO shelter in Dhaka, she then turned to us with a giant smile and proudly told us that this year she hopes to earn enough:

“To rent a mat in the shelter”

Her name is Sanjana, she is 12.

Through UCEP, she will become a computer technician.

For more, see: www.ucepbd.org

For the shelter where this student lived, see: www.seep.org.bd

Photos courtesy of www.ucepbd.org

Footnotes

- http://www.ucepbd.org/future/index.htm

You all no doubt remember the letters sent to you each year by Dan O’Gorman SC requesting donations for the UCEP Schools. Those of you who recently donated will be receiving pictures and short biographies of the children your donations have helped. Brasch and (Peachy) Keane recently saw first-hand those schools and those children who would otherwise remain largely illiterate and certainly living well below that country’s poverty line.

You all no doubt remember the letters sent to you each year by Dan O’Gorman SC requesting donations for the UCEP Schools. Those of you who recently donated will be receiving pictures and short biographies of the children your donations have helped. Brasch and (Peachy) Keane recently saw first-hand those schools and those children who would otherwise remain largely illiterate and certainly living well below that country’s poverty line. The other causes for entrance into the school as underprivileged, be it male or female, included: economic hardship; homeless; landless; river erosion; looking for work; and, family conflict. More than 20% of the students earned less than 11 Taka a day (AUD 13 cents). Sixty percent earned between 11 Taka to 25 Taka a day (AUD 30 cents). Twenty per cent lived under a tin shed wall, another 20% lived in tin sheds, whilst a little less than 10% specified their housing to be “a bamboo mat.”

The other causes for entrance into the school as underprivileged, be it male or female, included: economic hardship; homeless; landless; river erosion; looking for work; and, family conflict. More than 20% of the students earned less than 11 Taka a day (AUD 13 cents). Sixty percent earned between 11 Taka to 25 Taka a day (AUD 30 cents). Twenty per cent lived under a tin shed wall, another 20% lived in tin sheds, whilst a little less than 10% specified their housing to be “a bamboo mat.”