Your Honours, Colleagues, Friends,

First, may I thank you, Justice McMeekein, for the honour you have paid me in inviting me to propose the toast to the law this evening. As many of you know, my attendance at the CQLA conference from time to time is something of a homecoming. I am, proudly, a Rocky Boy. Bringing my family “back home” is always a joy. An opportunity for them to experience the warmth of this great community.

In fact, in a little over a month’s time, it will be the 30th anniversary of the completion of my schooling at St Joseph’s Christian Brothers College, West Street. And, one week after that, it will be the 30th anniversary of an event which occurred only metres from where we are gathered tonight. An event which would play a major part in my, initial, perception of the practice of the law.

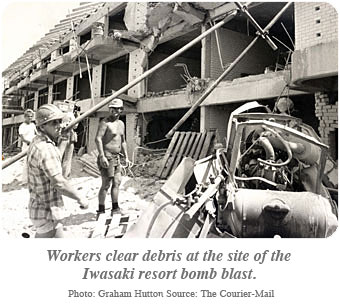

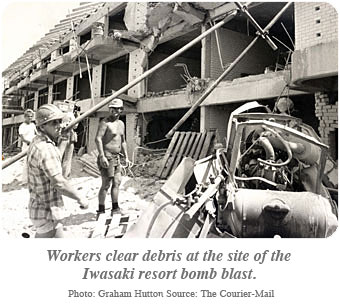

The event of which I speak is the bombing of two of the accommodation buildings at this resort, when it was then the yet to be completed and yet to be opened, Iwasaki Resort.

The event of which I speak is the bombing of two of the accommodation buildings at this resort, when it was then the yet to be completed and yet to be opened, Iwasaki Resort.

The bombing occurred at the conclusion of what would now be called “Schoolies” but which was then, somewhat less imaginatively, called “the Beach Week”.

When the bomb was detonated, it shook the ground and it could be felt where we were staying.

Like most young men who had recently completed senior, I arrived at the beach, staying not too far from here, with perhaps the faintest of hopes that there may be a moment during that week when the earth would move for me.

But I was thinking metaphorically, not literally.

I commenced articles, articled to John Shaw at Swanwick Murray & Roche, a few weeks later. My first week, it may even have been the first day, of my working life coincided with the arrest and appearance in the Rockhampton Magistrates Court of one John “Gunner” Guisman who had been charged with offences relating to the bombing. Mr Guisman had earned the soubriquet “Gunner”, as it would later be alleged, because he was always boasting, usually at the Railway or Club hotels in Yeppoon, that he was gunna’ do this or gunna’ do that. The particular boast that had made him a suspect in the investigation was, so it was alleged, that he was “gunna’ blow up the Jap”.

Many of you would recall that the building of the resort by Japanese interests, and matters concerning the title to the associated lands, had been highly controversial in the local community for some time. The Premier of the day had been a major supporter of the project. That had, perhaps, been reflected in the number of detectives who had been flown in from the South to find the bomber.

And so, in that first week, I walked along East Street, in 40 degree heat, to the Magistrates Court to find highly armed tactical response police securing the court. There were television crews with lights blazing and cameras rolling. There may even have been a chopper in the air.

There was no mistaking it — I had ticked the correct box on the QTAC form — the Law was the most exciting career on the planet. And Rocky was the place to practise it!

And this impression did not diminish in the ensuing months due to the continued activity that followed the bombing. Just before the commencement of the trial, I was playing tennis with Paul Braddy at his home. Paul was Mr Guisman’s solicitor. There was a call for Paul (on the house phone as it was still some 15 years from the advent of the mobile phone). He took the call and then explained to me that he would not be able to finish the set as a key witness, who until that time had been unable to be located, had suddenly been found. Paul had to meet with him immediately to take a statement. The excitement! This didn’t even happen to Perry Mason!

And then the trial itself.

I was there for its commencement, in the public gallery at the old Supreme Court, along with, so it seemed, half the population of Rockhampton. Ken McKenzie QC, later Crown Solicitor, Solicitor-General and Justice of the Supreme Court but who was then chief crown prosecutor, was leading the prosecution. Bob Greenwood was for the defence. The trial commenced with an application by Greenwood for bail for his client for the duration of the trial. If bail were to be granted, Greenwood said, Mr Guisman would not go near the Iwasaki land. The judge said that this was all very well, but that it was quite unhelpful as he had no understanding of where the land was, and thus where Mr Guisman undertook that he would not go.

With perfect timing, and to assist the judge in his understanding of these matters, Greenwood produced a copy of the map of the lands, which was a schedule to the Queensland International Tourist Centre Agreement Act 1978. It disclosed quite a tract of land, of which the resort itself was only a tiny part.

“That? All that?”; asked the judge.

“Yes”: answered Greenwood.

“Bail granted”: said the judge.

In the end, Mr Guisman was acquitted.

To a wide eyed 17 year old it seemed wonderful theatre. But, of course, it was not. It was so much more than that.

It was the resolution of the tension between, on the one hand, the right of the public to be protected from, and for the State to punish, criminal acts of violence (and have no doubt – in today’s parlance this bombing easily would fit the description of an act of terrorism) — and on the other hand a citizen’s right to liberty which is only to be removed after proof of the charge against him or her beyond reasonable doubt after a fair trial. It was the law in action.

May I briefly mention something of the local profession at that time? The Rockhampton Bar of that time proved to be a veritable departure lounge for judicial office. The resident crown prosecutor was Marshall Irwin, who was soon followed by Kerry O’Brien. The private Bar comprised Messrs Hall, Dodds, Jones, White, Britton — and the young athletic one, McMeekin. Every one of those gentleman would be appointed to either the District Court, or in the cases of Jones and McMeekin, the Supreme Court.

I always liked the young bloke McMeekin. Whenever you delivered a brief (and I mean the act of physically walking a brief around to his chambers — that was the extent of my authority) he was very friendly and welcoming. Always ready for a chat, sometimes a cup of tea over which we would discuss recent selections in the Australian rugby team. He agreed with me that Ella was to be preferred to McLean at 5/8th. He ticked all the boxes. He was truly a good bloke.

I would later discover, through my own professional need, that such charm and faux hospitality is extended by all at the bottom of the foodchain at the bar to even the most lowly of articled clerks in the hope that it may bring work.

Upon appointment to the judiciary, each of those gentlemen took an oath of office in which they swore to do equal justice to the poor and rich and discharge the duties of their office according to the law to the best of their knowledge and ability without fear, favour or affection. These are not hollow words of mere ceremony. They are, in short form, the embodiment of our system of law.

Chief Justice, we the people of Queensland, are deeply indebted to you and grateful for your selfless service to us as a Justice of the Supreme Court for now in excess of a quarter of a century, the last 12 as our Chief Justice.

Justice McMeekin, Judge Britton, Magistrates Carroll and Press, Acting Magistrate Morrow, we are grateful to you for your administration of justice according to law in this region.

May I return then to another Central Judge, and another connection with Japan?

Mr Justice D M Campbell was Central Judge from the mid 1960’s to the early 1970’s (It was as his Honour’s first associate that Paul Braddy came to Rockhampton). But it is of a time prior to his becoming a judge that I wish to speak.

Like so many of his brother judges of that age, DM Campbell had served in the second world war. Upon the surrender of the Japanese in the Pacific, he was, because of his legal training, assigned duties as defence counsel for a number of Japanese officers and soldiers charged with war crimes. At the conclusion of one trial, the commanding officer of a number of soldiers with whom he was co-accused wrote the following letter of thanks to Campbell.

“For your labours as leader of the defence in the trial of nine of my subordinates, my defendants and I express our thanks. Last night I read in detail the record of your pleading in the courtroom. Our feelings are overwhelming when we realize that you, an Australian charged with the defence of accused who were Japanese faced your task with an attitude of impartiality, laying aside all feelings as an Australian, and gave all that you had to the work. As you not only said all that we would have wanted said, but also pointed out countless things that we could not possibly have thought of, everyone of the accused is absolutely satisfied. We have now to await the verdict, but — having had the finest possible defence — we have not an ounce of regret, whatever the outcome be.”

Campbell had done his duty. Not merely his duty to carry out the command of his orders, but his duty also to his clients – people who were so recently his enemies and who had been charged with atrocities against his comrades – and, ultimately, his duty to the law.

You see that Japanese officer, who was executed for his crimes, knew that he had been, as Mr Guisman many years later also would be, although to very different ends, the beneficiary of justice according to Law.

I can think of no finer exemplar to us all than this of the law which we are all happy, humbled and honoured to serve.

I give you a toast: To the law.

The event of which I speak is the bombing of two of the accommodation buildings at this resort, when it was then the yet to be completed and yet to be opened, Iwasaki Resort.

The event of which I speak is the bombing of two of the accommodation buildings at this resort, when it was then the yet to be completed and yet to be opened, Iwasaki Resort.