That struggle today owes as much to the varied sources of contemporary jurisprudence, as it does to our common law heritage, and the diffuse origins of our legal system. It has thus been said that one of the most fundamental tasks of the modern lawyer ‘… is to integrate rules from [those] different sources into a coherent whole.’2

The Australian legal system is drawn from a diverse range of statutory and non-statutory sources. Speaking extra-judicially in 1943, Sir Owen Dixon made reference to the ‘… surprisingly large number of successive legislative bodies …’ which had by then contributed to the statute law of this country.3 The ‘unwritten’ or general law of this country is similarly multifarious, owing its origins to the numerous courts and tribunals which once comprised the divided English legal system.

Some Historical Comparisons

Some Historical Comparisons

In a manuscript published posthumously in 1713, Sir Matthew Hale touched upon the diversity within the various population groups that have all contributed to the unwritten municipal laws of England:

‘The Kingdom of England being a very ancient Kingdom, has had many Vicissitudes and Changes … under several either Conquests or Accessions of Foreign Nations. For tho’ the Britains were, as is supposed, the most ancient Inhabitants, yet there were mingled with them, or brought in upon them, the Romans, the Picts, the Saxons, the Danes, and lastly, the Normans; and many of those Foreigners were as it were incorporated together, and made one Common People and Nation; and hence arises the Difficulty, and indeed Moral Impossibility, of giving any satisfactory or so much as probable Conjecture, touching the Original of the Laws …’4

A movement towards integration of the many and varied strands of substantive and procedural law which have together emerged from this multitude of sources can be traced through the centuries of history of the various institutions that comprised the divided legal system. That movement can be identified, for example, in the very origins of the common law, to a time when a central feudal Council began to dispense royal justice in competition with the multitude of ecclesiastic and secular jurisdictions which then comprised the English legal system, and the very development of a body of law which was ‘common’ to the entirety of the Kingdom.

A concern for coherence may also be detected in the very technique of the common law — in the common law philosophy of incrementalism and development by analogy; the process of reasoning upwards from decided cases, rather than downwards from abstract generalisations; and in the trend towards integration of the otherwise disparate rules and principles so derived into a single coherent whole. In the words of Baron Parke of the Exchequer:

‘Our common law system consists in the applying to new combinations of circumstances those rules of law which we derive from legal principles and judicial precedents; and for the sake of attaining uniformity, consistency, and certainty, we must apply those rules, where they are not plainly unreasonable and inconvenient, to all cases which arise; and we are not at liberty to reject them, and to abandon all analogy to them, in those to which they have not yet been judicially applied, because we think that the rules are not as convenient and reasonable as we ourselves could have devised.5

Similar sentiments resonate today. In an extra-judicial speech delivered in January, 2008,6 Gleeson CJ emphasised the need for coherence as a legal value having a particular influence in the development of the law of tort. In that same speech, the then Chief Justice also identified the need for certainty and predictability of legal outcome as another important value in contemporary judicial decision-making.

The centuries of development of the various legal ‘streams’ from which our general law has evolved were characterised by institutional jealousy and self-interest, and by the struggle for jurisdiction. One of the results of those centuries of jurisdictional conflict was a refashioning of the substantive law administered within the individual jurisdictional streams into individual branches of law that were capable of a largely peaceful co-existence. As will be shown, this happened not so much as a result of any conscious forethought or design, but as the largely unintended consequence of centuries of conflict between various institutions that made up the divided legal system.

The common law owes its existence to a period when the courts which administered ‘the King’s justice’ were few among many. During the centuries of evolution of the forms of action, from which the common law itself ultimately derived, a rational and coherent legal system was by no means the foremost concern of those responsible for administering the King’s justice. Self-interest, and active competition for the work of other courts and tribunals which comprised the divided legal system, were entirely more motivating influences. In the words of Maitland:

“So long as the forms of action were still in use, it was difficult to tell the truth about their history. There they were, and it was the duty of the judges and text writers to make the best of them, to treat them as though they formed a rational scheme provided all of a piece by some all-wise legislator. It was natural that lawyers should slip into the opinion that such had really been the case, to suppose, or to speak as they supposed that some great king … had said to his wise men ‘Go to now! a well ordered state should have a central tribunal, let us then with prudent forethought analyse all possible rights and provide a remedy for every imaginable wrong.’ It was difficult to discover, difficult to tell the truth, difficult to say that these forms of action belonged to very different ages, expressed very different and sometimes discordant theories of law, had been twisted and tortured to inappropriate uses, were the monuments of long-forgotten political struggles; above all it was difficult to say of them that they had their origin and their explanation in a time when the king’s court was but one among many courts.”7

Yet, whether through ‘prudent forethought’ or otherwise, a measure of order was ultimately realised. By the turn of the eighteenth century, trespass and its progenitors (particularly assumpsit and trover) had emerged as the only forms of action in common use within the English common law.8 Active competition for jurisdiction amongst the courts and tribunals which then comprised the divided English legal system had also, by then, had a substantial impact upon the law administered in other jurisdictions.

Yet, whether through ‘prudent forethought’ or otherwise, a measure of order was ultimately realised. By the turn of the eighteenth century, trespass and its progenitors (particularly assumpsit and trover) had emerged as the only forms of action in common use within the English common law.8 Active competition for jurisdiction amongst the courts and tribunals which then comprised the divided English legal system had also, by then, had a substantial impact upon the law administered in other jurisdictions.

As Maitland noted, the struggle for jurisdiction played a critical part in the centuries of development of the English legal system. During the early years (particularly the years prior to the political struggles which led to the civil war), the jurisdictional conflict between the common law courts themselves (especially the Kings Bench and the Common Pleas) was far more pronounced than any early tensions between the common lawyers and the civilians.9

By the early seventeenth century, however, the civilian jurisdictions (which included the Court of Requests, the High Court of Chivalry and the Ecclesiastical Courts) were feeling distinct pressure from the common law courts, and the High Court of Admiralty had become the focus of that pressure.10 The underlying cause of the conflict between the common law courts and the civilian jurisdictions went beyond mere jurisdictional imperialism on the part of the common lawyers, and was as much philosophical as it was tangible. The English civilians were philosophically committed to cosmopolitanism and to the ideal of a rational legal science, and they strove for a universal test of reason.11 The development of the common law, in contrast, was characterised by its inherent insularity. The civilians’ ideals thus lay in stark contrast to the localised orientation of the common lawyers.

The most profound philosophical differences between the common lawyers and the English civilians, however, concerned the respective sources of the law that they applied in the development of their jurisprudence. While the common lawyers focussed upon localised precedent and custom, the civilians looked routinely to foreign sources for guidance and principle, in the belief that legal systems can be tested by reference to natural reason.12

The civilians also rejected the idea that legal doctrine should develop through incremental decision-making.13 The cosmopolitanism of the civilians led to accusations by the common lawyers of civilian subordination to foreign religious or political authority.14 These fundamental philosophical differences had become apparent by the late sixteenth century.

The conflict between the High Court of Admiralty and the courts of common law also involved a distinctly political aspect. The infiltration of civil and canon law into the English legal system was perceived not merely as a threat to the autonomy of the common law system, but as an infringement upon the very sovereignty of the kingdom. Any dependency upon laws derived from foreign sources was thought by the common lawyers to derogate from the ‘honour and integrity’ of the kingdom itself.15 Thus, in their issue of writs of prohibition against the High Court of Admiralty, the courts of common law were in many cases acting to prevent the admiralty from erroneously applying what they perceived to be alien legal principles to the resolution of controversies that were properly determinable by reference to domestic law. Viewed in that manner, in their issue of prohibition against the High Court of Admiralty, the courts of common law were not purporting to alter the law or to limit or control accrued rights. They were merely preventing the High Court of Admiralty from illegitimately applying foreign law to the resolution of disputes that were properly determinable by reference to domestic law.16

That is not to say that the common lawyers were entirely resistant to the ‘foreign’ doctrine applied in admiralty. Indeed, the common law courts were occasionally prepared not merely to condone the exercise of admiralty jurisdiction, but to extend common law protection to entitlements that were otherwise peculiarly enforceable in admiralty.17 In other areas too, if municipal jurisprudence was not sufficiently developed to deal with particular areas of controversy, the common law courts were prepared to actively borrow from admiralty jurisdiction to ensure that justice was done.18 And within English law at least, a close analysis will show that the municipal lawyers played at least as prominent a role as the civilians themselves in the jurisprudential development of what is thought to be the quintessentially civilian construct: the maritime lien.19

The emergence of the maritime lien as the mainstay of the general jurisdiction in admiralty provides a useful example of how a largely uncontentious co-existence was eventually achieved between two otherwise conflicting jurisdictional streams.

The emergence of the maritime lien as the mainstay of the general jurisdiction in admiralty provides a useful example of how a largely uncontentious co-existence was eventually achieved between two otherwise conflicting jurisdictional streams.

By as late as the mid-nineteenth century, the English courts had not yet adverted to the maritime lien as a distinct legal concept, and nor had they abstracted any conceptual rationalisation for the range of claims that were capable of enforcement in the exercise of the admiralty court’s inherent jurisdiction in rem. It was in the reasoning of a common lawyer, the then Chief Justice of the Common Pleas – Sir John Jervis, that the concept of the maritime lien first came to be acknowledged within English law as a discrete legal concept. In 1851, sitting as part of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the matter of the Bold Buccleugh, the then Chief Justice of the Common Pleas gave the decision for the Board. Drawing heavily upon the contents of an American decision known as the Nestor,20 delivered some two decades earlier, Sir John Jervis identified and described that maritime lien in the following terms:

A maritime lien does not include or require possession. The word is used in Maritime Law not in the strict legal sense in which we understand it in Courts of Common Law…but to express, as if by analogy, the nature of claims which neither presuppose nor originate in possession. This was well understood in the Civil Law, by which there might be a pledge with possession, and a hypothecation without possession, and by which in either case the right travelled with the thing into whosesoever [sic] possession it came. Having its origin in this rule of the Civil Law, a maritime lien is well defined by Lord Tenterden, to mean a claim or privilege upon a thing to be carried into effect by legal process; and Mr Justice Story explains that process to be a proceeding in rem, and adds, that wherever a lien or claim is given upon the thing, then the Admiralty Forces it by a proceeding in rem, and indeed is the only Court competent to enforce it. A maritime lien is the foundation of the proceeding in rem, a process to make perfect a right inchoate from the moment the lien attaches…This claim or privilege travels with the thing, into whosesoever possession it may come. It is inchoate from the moment the claim or privilege attaches, and when carried into effect by legal process, by a proceeding in rem, relates back to the period when it first attached.21

Through the vehicle of the maritime lien, the day to day business of the High Court of Admiralty became confined to those areas of admiralty business in which the courts of common law were either unable or unwilling to assist litigants. Within those areas, the utility of admiralty procedures and remedies came to be acknowledged and accepted by the courts of common law. In Ouston v Hebden,22 for example, prohibition was sought to restrain an action in rem by a co-owner of a ship. In declining to prohibit the action in its totality, Lee C.J. observed:

‘I have no doubt but the Admiralty has a power in this case to compel a security, for this is a proceeding in rem and not in personam; and this jurisdiction has been allowed to that Court for the public good …’23

Similarly, in Menetone v Gibbons,24 prohibition was declined in respect of an action in rem to enforce a bottomry bond, with Lord Kenyon C.J. commenting:

‘On the principal question in this case there can be no doubt; it has been settled for this last century … that the Court of Admiralty has jurisdiction in a case like the present. And indeed it would be highly inconvenient if it were otherwise, because that Court proceeds in rem, whereas the Courts of Common Law can only proceed against the parties.’25

Within these areas of admiralty business in which the courts of common law were either unable or unwilling to intrude, the action in rem came to be acknowledged as performing a service that could not be achieved by the municipal courts. Within these areas, the administration of a jurisdiction in rem was effectively conceded to the High Court of Admiralty for the public convenience.

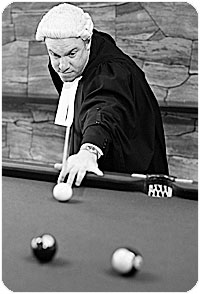

By this process, two discrete, sometimes overlapping, and sometimes conflicting, jurisdictions were brought into largely harmonious co-existence. While, by their own account, the courts of common law in their issue of prohibition against the High Court of Admiralty were merely acting to prevent an inferior court from illegitimately applying foreign law to the resolution of disputes properly justiciable under domestic law, they were also inspired by less principled objectives. A more elementary inspiration for the common lawyers’ day to day competition for judicial business was revealed in the course of the nineteenth by Lord Campbell in the matter of Scott v Avery in the following passage:

‘Now, I wish to speak with great respect of my predecessors the judges; but I must just let your Lordships into the secret of that tendency. My Lords, there is no disguising the fact, that as formerly the emoluments of the judges depended mainly or almost entirely of fees, and they had no fixed salary, there was great competition to get as much as possible of litigation into Westminster Hall, and a great scramble in Westminster Hall for the division of the spoil …’26

Within the context of the divided legal system, the process of rationalisation of the competing jurisdictional streams can thus be seen to have occurred not so much as a result of any particular forethought or design on the part of the lawmakers, but as a largely unintended consequence of centuries of jurisdictional struggle between competing courts and tribunals.

An at least implicit desire for jurisprudential coherence was nevertheless reflected in the aspirations and philosophies of prominent English jurists such as Lord Mansfield who disliked the separation between the common law and equity.27 A similar aspiration might be thought to have influenced the policies that supported the succession of statutory reforms which culminated in the implementation of the judicature reforms with effect from 1 November, 1875.28

Some Contemporary Dynamics

In contemporary jurisprudence on the other hand, the push for coherence manifests itself in a number of ways. It is from time to time influential in the development of individual general law streams, particularly in marginal cases at the fringe of legal orthodoxy. It is a value which can be seen to play a role in statutory interpretation, and at the interface between statute and the general law. And it is a value which lies at the very core of certain established legal principles which regulate the availability of particular bodies of law, and which serve to prevent overlap in their day to day functioning.

A need for coherence in the law has in recent years proven influential in the disposition of a number of marginal cases in which litigants have sought to extend general law concepts and principles beyond their established bounds. In 2001, for example, in the matter of Sullivan v Moody,29 the High Court was called upon to consider whether a common law duty of care might be owed by those responsible for investigating and reporting upon cases of alleged child abuse to those suspected of having committed the abuse. A unanimous bench denied the existence of any common law duty of care in those circumstances out of an expressed concern for ‘… the coherence of the law’.30 In another matter more recently determined by the New South Wales Court of Appeal, one of the grounds upon which that court denied the existence of a common law duty of care on the part of a governmental employer to conduct its disciplinary procedures so as to avoid psychiatric harm to an employee was an expressed concern that the imposition of a duty of that kind would give rise to issues of compatibility and coherence between the law of tort, on the one hand, and statute, contract and administrative law, on the other.31

A need for coherence in the law has in recent years proven influential in the disposition of a number of marginal cases in which litigants have sought to extend general law concepts and principles beyond their established bounds. In 2001, for example, in the matter of Sullivan v Moody,29 the High Court was called upon to consider whether a common law duty of care might be owed by those responsible for investigating and reporting upon cases of alleged child abuse to those suspected of having committed the abuse. A unanimous bench denied the existence of any common law duty of care in those circumstances out of an expressed concern for ‘… the coherence of the law’.30 In another matter more recently determined by the New South Wales Court of Appeal, one of the grounds upon which that court denied the existence of a common law duty of care on the part of a governmental employer to conduct its disciplinary procedures so as to avoid psychiatric harm to an employee was an expressed concern that the imposition of a duty of that kind would give rise to issues of compatibility and coherence between the law of tort, on the one hand, and statute, contract and administrative law, on the other.31

A similar ideal may also be relevant to the construction of statutes, and to the broader interaction between statute and the general law. It is worth recalling after all, as Lord Steyn observed in R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Pierson,32 that the common law and statute law must ultimately ‘… coalesce in one legal system’.33

At one level, coherence is served by the idea that an Act should be interpreted in such a way that all of its various integers operate congruously and harmoniously.34 It is also evident at the interface between statute and the general law — in the idea that Parliament does not legislate in a vacuum, and that legislation must be interpreted with due regard to contextual rights, freedoms and immunities.35 It has thus become acknowledged that it is sometimes appropriate for courts taxed with the interpretation of legislation to take express account of the need for coherence in the law.36

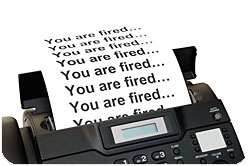

The natural development of the general law may also be affected by statute, and by the need to ensure coherence with statutes. In Johnson v Unisys Limited,37 the House of Lords rejected the appellant’s claim for common law damages for unfair dismissal on the ground that a newly developed common law right of the kind contended for would cover the same ground as rights which had been expressly provided for by statute. As Lord Hoffmann explained:

The natural development of the general law may also be affected by statute, and by the need to ensure coherence with statutes. In Johnson v Unisys Limited,37 the House of Lords rejected the appellant’s claim for common law damages for unfair dismissal on the ground that a newly developed common law right of the kind contended for would cover the same ground as rights which had been expressly provided for by statute. As Lord Hoffmann explained:

‘… judges, in developing the law, must have regard to the policies expressed by Parliament in legislation. Employment law requires a balancing of the interests of employers and employees, with proper regard not only to the individual dignity and worth of the employees but also to the general economic interest. Subject to observance of fundamental human rights, the point at which this balance should be struck is a matter for democratic decision. The development of the common law by the judges plays a subsidiary role. Their traditional function is to adapt and modernise the common law. But such developments must be consistent with legislative policy as expressed in statutes. The courts may proceed in harmony with Parliament but there should be no discord.’38

Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead concluded that the common law right propounded by the appellant could not satisfactorily co-exist with the existing statutory right provided for by Parliament, given that it would ‘fly in the face’ of various limits prescribed by the legislature.39

Choices and Subordination

One of the requirements for a seamless interaction between the different bodies of law that comprise a unified legal system is the need to avoid potentially inconsistent overlap between discrete bodies of law in terms of their potential application to the circumstances of any given dispute. Prior to the judicature reforms, jurisdictional overlap was largely avoided by the jurisdictional divisions within the English legal system, and by the remedial and institutional superiority of different parts of that divided legal system. With institutional unification of the system, those responsible for the judicature reforms perceived a specific need to resolve any potential future conflict between at least rules of common law and those of equity, and stipulated expressly that in the event of any such conflict or variance the rules of equity would prevail.40

The general law has developed various other rules and principles which serve to regulate the choices available in circumstances of such potential conflict. Some of the more obvious rules and principles of this kind have developed within the realm of private international law. Others are confined within the realm of domestic law proper.

It was only in the latter part of the nineteenth century that it became accepted within the courts of common law that English courts might legitimately apply foreign law to the resolution of the disputes that came before them. As late as 1760, in the matter of Robinson v Bland,41 Justices Dennison and Wilmot of the Kings Bench (with Mansfield CJ dissenting) preferred the idea that a litigant who seeks the assistance of an English court must be prepared to submit to the law of England for resolution of the relevant dispute.42

By the close of the eighteenth century, however, the courts of common law were willing to acknowledge that English municipal courts might legitimately apply foreign legal doctrine to the resolution of controversies before them.43 Since that time, a series of principles have of course emerged to regulate the choice of law questions that are from time to time presented by the putative application of foreign law within the courts of the forum.

Even within the confines of domestic law there is the possibility of overlap between different bodies of law in the day to day functioning of the courts. Rules have developed in a number of areas which have the effect of subordinating particular bodies in circumstances of potential conflict.

A rule has developed, for example, at the interface between law and equity which effectively subordinates the remedies offered by the common law to those available in equity in the circumstances to which the rule applies. This rule is particularly identifiable in circumstances where a dispute has arisen between the members of a partnership, or between participants in a joint venture characterised by the existence of fiduciary duties inter se.

In disputes of that character, the existence of a fiduciary relationship between the parties is apt to engage the exercise of equitable jurisdiction,44 and to do so to the exclusion of the common law remedies that might otherwise lie. This is because the fiduciary relationship has traditionally attracted the exercise of equitable jurisdiction,45 to the virtual exclusion of jurisdiction at common law.46

It was for this reason, for example, that in the absence of any specific settlement between the parties,47 an action at law was not maintainable between the parties to a fiduciary relationship to the extent that it involved any question requiring the taking of an account. The courts of common law were considered to be without the remedial flexibility to do justice in disputes of that kind.

It was for this reason, also, that an action in trover (or conversion as it is now known) was not maintainable by one partner against another involving a complaint as to the disposition of a partnership asset.48 The limit of any given partner’s rights in such circumstances was to have an account taken in the exercise of the court’s equitable jurisdiction, and to be paid any balance that might be found due upon the taking of the account.49

It was for this reason, too, that an action for moneys had and received was not available to a partner seeking to recover against another who had, subsequent to a dissolution, applied a partnership asset in satisfaction of an asserted partnership liability.50 Until an account has been taken, a common law action was considered premature,51 with the claimant’s remedy lying properly in equity, and not at law.52

The judicature reforms have in no way altered this fundamental remedial limitation. In Wilson v Carmichael,53 for example, the High Court affirmed orders under appeal which took effect to restrain a litigant from proceeding with a common law claim for moneys had and received pending the winding up of a partnership and the taking of an account. In Green v Hertzog,54 a claim by a partner who had instituted a common law action to recover monies said to have been advanced by way of loan to a partnership was described as ‘misconceived’ by the English Court of Appeal. It was instead held in that matter that the only way that the money concerned could be recovered was through the remedy of account.

The English Court of Appeal’s reasoning in Green v Hertzog was more recently approved by the House of Lords in Hurst v Bryk.55 In his speech in Hurst v Bryk, Lord Millett observed that:-

‘By entering into the relationship of partnership, the parties submit themselves to the jurisdiction of the court of equity and the general principles developed by that court in the exercise of its equitable jurisdiction in respect of partnerships. There is much to be said for the view that they thereby renounce their right by unilateral action to bring about the automatic dissolution of their relationship by acceptance of a repudiatory breach of the partnership contract, and instead submit the question to the discretion of the court.’56

By subordinating common law principles and remedies in these circumstances, the courts can avoid the possibility of competing (and possibly inconsistent) legal principles being brought to bear in the resolution of any given dispute. By subordinating one branch of the law in such circumstances, a harmonious co-existence may be ensured.

A similar rule operates at the interface between contract and restitution. What has become known as the ‘subsidiarity’ principle dictates that in circumstances where a contract is effective between two parties, the contractual allocation of risk as between the parties cannot be subverted by the application of restitutionary principles to those same facts and circumstances.57 In other words, in circumstances where a contract is effective between two parties the law of restitution must effectively yield to the law of contract so as to avoid possibly inconsistent overlap.58 It has been acknowledged by the High Court that in the development of the law of restitution, no less than elsewhere, the courts must strive to ensure coherence and harmonious co-existence with other branches of the law.59

Conclusion

Conclusion

In Woolcock Street Investments Pty Ltd v CDG Pty Ltd,60 McHugh J observed that the law today is too complex to be a seamless web, and that the courts should, so far as possible, strive for coherency in the law’s principles and policies. As has been shown, the goal of coherence has today assumed an acknowledged place in the development of the individual jurisdictional streams, and in their interaction within our unified legal system.

As an ideal, coherence may be influential not just in the adjudication of marginal or novel cases, but also in the process by which courts administering a given jurisdiction are sometimes able to draw upon principles or apply remedies which owe their origin to an entirely different branch.61 It can also play a role in the incremental development of jurisdictional streams to fill ‘gaps’ left in other areas.62

Coherence is also today served by the idea that the local laws of the various States and Territories which comprise the Commonwealth are not to be treated as if they were each discrete legal systems.63 It is further reflected in the idea that Australian courts administer a uniform common law throughout the various ‘law areas’ which constitute the Commonwealth.64

It is worth remembering, after all, that the law of this country must be regarded as a single unit, its content comprising both legislation and the common law. In the words of Sir Owen Dixon, the common law must be treated as ‘… antecedent in operation to the constitutional instruments which first divided Australia into separate colonies and then unified her in a federal Commonwealth’.65 And as that great jurist also observed, the ‘… anterior operation of the common law is not just a dogma of our legal system, an abstraction of our constitutional reasoning. It is a fact of legal history.’66

M.A. Jonsson

TRINITY CHAMBERS

Footnotes

- (2005) 203 CLR 660, at para [27].

- P. Birks (ed.), 1, English Private Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 12.

- O. Dixon, Jesting Pilate and Other Papers and Addresses (Collected by Woinarski, Sydney: Law Book Company, 1965), 201.

- M. Hale, The History of the Common Law of England (C.M. Gray (ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 39.

- Mirehouse v Rennell (1833) I Cl. & F. 527, 546 (5 ER 759; 6 ER 1015, 1023).

- M. Gleeson, ‘The Role of a Judge in a Representative Democracy’, Speech presented to the Judiciary of the Commonwealth of the Bahamas, 4 January, 2008.

- F.W. Maitland, The Forms of Action at Common Law, A Course of Lectures (ed. By A.H. Chaytor and W.J. Whittaker, London: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 9.

- Id. 58.

- D.R. Coquillette, The Civilian Writers of Doctors’ Commons, London. Three Centuries of Juristic Innovation in Comparative Commercial and International Law (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1988), 31-32.

- Coquillette, 102-103.

- Coquillette 8.

- Coquillette 32-33.

- Coquillette 8.

- Ibid.

- M. Hale, The History of the Common Law of England. Edited by C.M. Gray (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 47.

- See, for example, The Neptune (1835) 3 Knapp. 94, 116 (12 ( E.R. 584, 592).

- For example, by allowing a common law possessory lien to be asserted by a salvor seeking to secure an entitlement to salvage reward — see Hartford v Jones (1698) 1 Ld. Raym. 393 (91 E.R. 1161).

- An example of this particular phenomenon is instanced by the common lawyer’s absorption of the admiralty jurisprudence of general average (to the virtual exclusion of the High Court of Admiralty) through the common law action for indebitatus assumpsit — see, for example, Birkley v Presgrave (1801) 1 East. 220 (102 E.R. 86).

- By the turn of the nineteenth century, the concept of the maritime lien was virtually unrecognisable within the jurisprudence of the civilians who practised in admiralty. In the second edition of his influential work upon the civil law and the law of admiralty published in 1802, for example, Arthur Browne in terms denied that circumstances that might expose a ship to arrest and sale in the exercise of a court’s admiralty jurisdiction might properly be said to give rise to an hypothecation of the ship, or to produce any lien thereon — see A. Browne, 2 A Compendious View of the Civil Law, and of the law of Admiralty (2nd ed., London: Butterworth, 1802), at 143. By that time, however, the defining characteristics of the maritime lien and of the personification theory of the action in rem had nevertheless become reasonably well developed. The emergence and evolution of these characteristics can be traced to decisions of the municipal courts delivered more than a century earlier — in matters such as Clay v. Sudgrave (1700) 1 Salk. 33 (91 E.R. 34), Corset v. Husely (1688) Comb. 135 (90 E.R. 389) and Wells v. Osman (1704) 2 Ld. Raym. 1044 (92 E.R. 193). The Chancery, too, can be seen to have played an important part in the recognition of those features that distinguish the maritime lien from any comparator within the municipal streams — compare Watkinson v. Bernadiston (1726) 2 P. Wms. 368 (24 E.R. 769) and Hussey v. Christie (1807) 13 Ves. Jun. 594 (33 E.R. 417). It was only from about the turn of the nineteenth century that the High Court of Admiralty came to expressly recognise the concept of the lien as synonymous with that court’s authority to exercise its jurisdiction in rem — see, for example, the Two Friends (1799) 1 C. Rob. 271 (165 E.R. 174), the Batavia (1822) 2 Dods. 500 (165 E.R. 1559) and the Eleanor Charlotta (1823) 1 Hagg. 156 (166 E.R. 56).

- (1831) 18 Fed. Cas. 9.

- (1851) 7 Moo. P.C. 267, 284-285 (13 E.R. 884, 890-891).

- (1745) 1 Wils. K.B. 101 (95 E.R. 515).

- See also, for example, Blacket v Ansley (1697) 1 Ld. Raym. 235 (91 E.R. 1053); Lambert v Aeretree (1697) 1 Ld. Raym. 223 (91 E.R. 1045); Degrave v Hedges (1707) 2 Ld. Raym. 1285 (92 E.R. 343) and Dimmock v Chandler (1731) Fitz-G. 197 (94 E.R. 717).

- (1789) 3 T.R. 267 (100 E.R. 568).

- See also, for example, Johnson v Shippin (1704) 1 Salk. 35 (91 E.R. 37).

- (1857) 28 LT 207 — The practice of remuneration of Judges by recourse to court fees was not abolished within the English legal system until 1826.

- W.S. Holdsworth, ‘Equity’ (1935) 51 Law Quarterly Review 142, 148; W.S. Holdsworth, ‘Blackstone’s Treatment of Equity’ (1929) 43 Harvard Law Review 1, 27.

- With the commencement of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873 (U.K.) in amended form on that date. While the impact of the judicature reforms upon adjectival law was undoubtedly profound, the effect of those reforms upon the substantive law of England has proven more controversial. Indeed, the debate as to the extent to which the judicature reforms have impacted upon substantive Anglo-Australian jurisprudence continues today – see, for example, J. Edelman and S. Degeling, ‘Fusion: The Interaction of Common Law and Equity’ (2004) 25 Australian Bar Review 195.

- (2001) 207 CLR 562.

- (2001) 207 CLR 562, at para. [55]; and see also the reasoning of Gleeson CJ in the matter of Tame v New South Wales (2002) 211 CLR 317, at para [28].

- State of New South Wales v Paige (2002) 60 NSWLR 371; and see, particularly, the reasoning of Spigelman CJ at para. [95].

- [1998] AC 539.

- [1998] AC 539, at 589.

- Eastman v Director of Public Prosecutions (ACT) (2003) 214 CLR 318, at para [85].

- In other words, in the development and functioning of the various interpretive presumptions which are today considered to fall within the ambit of the overarching concept that has become known as the legality principle — see the passage within the speech of Lord Hoffmann in R v Home Secretary; ex parte Simms [2002] 2 AC 115, at 131; which has since been expressly approved and adopted by Gleeson CJ in Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth (2003) 211 CLR 476, at para [30]; and by Kirby J in Daniels Corporation International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002) 213 CLR 543, at 582. Compare also J. Spigelman, ‘The Principle of Legality and the Clear Statement Principle’, Speech presented to the New South Wales Bar Association Conference, 18 March, 2005

- See the observations of Gleeson CJ in Purvis v New South Wales (2003) 217 CLR 92, at para [7]; and those of Callinan J in Sons of Gwalia Ltd v Margaretic (2007) 81 ALJR 525, at para [255].

- [2003] 1 AC 518.

- [2003] 1 AC 518, at para [37].

- [2003] 1 AC 518, at para [2].

- Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873 (UK), s. 25(11). The same stipulation applies in Queensland today by force of s. 249 of the Supreme Court Act 1995.

- (1760) 1 Black. W. 256 (96 ER 141).

- (1760) 1 Black. W. 256, 262-262 (96 ER 141, 142-143).

- See, for example, the reasoning of Lord Mansfield in Mostyn v Fabrigas (1774) 1 Cowp. 161, 173-174 (98 ER 1021, 1028) and Holman v Johnson (1775) 1 Cowp. 341, 343 (98 ER 1120, 1121). Compare also the comments of Eyre CJ in Melan v The Duke de Fitzjames (1797) 1 Bos & Pul 138 (126 ER 822).

- And it matters not that the relationship might not be able to be susceptible to characterisation as a partnership in the strict sense — compare, for example, Russell v Austwick (1826) 1 Sim. 52 (57 ER 498); McInroy v Hargrave (1867) 16 LT 509; and United Dominions Corporation Ltd v Brian Pty Ltd (1985) 157 CLR 1.

- See Makepeace v Rogers (1865) 4 De G & S 649 (46 ER 1070).

- The limited extent to which the common law courts retained an active jurisdiction in this area was described in Tate v Barry (1928) 28 SR (NSW) 380, at 383.

- As to which, see for example, Jackson v Stopherd (1834) 2 C & M 361 (149 ER 800); Wiles v Woodward (1850) 5 Ex 556 (155 ER 244).

- Fox v Hanbury (1776) 2 Cowp 445 (98 ER 1179).

- Fox v Hanbury, at 449 (1181).

- Harvey v Crickett (1816) 5 M & S 336 (105 ER 1074).

- Harvey v Crickett, at 340 (1075-1076); and see also Woodbridge v Swan (1833) 4 B & Ad 633 (110 ER 594).

- Morgan v Marquis (1853) 23 LJ Exch 21, at 23.

- (1905) 2 CLR 190.

- [1954] 1 WLR 1309.

- [2002] 1 AC 185, 194.

- [2002] 1 AC 185, 194, at 196 — and see also, for example, Mullins v Laughton [2003] Ch 250.

- See the comments of Mason P of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in the matter of Nikolic v Oladaily Pty Ltd [2007] NSWCA 252, at para [101].

- See, for example, the reasons of Kirby J in Roxborough v Rothmans of Pall Mall Australia Pty Ltd (2001) 208 CLR 516, at para [166].

- The need for coherence in this area was recently recognised in the joint reasons of Gummow, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ in Lumbers v W Cook Builders Pty Ltd (In Liquidation) [2008] HCA 27, at para [78].

- Woolcock Street Investments Pty Ltd v CDG Pty Ltd (2004) 216 CLR 515, at para [102].

- During the centuries of development of the common law, for example, the common law frequently drew upon laws and customs administered in other courts and tribunals in the development of its own jurisprudence (and often to the ultimate exclusion of that jurisprudence from the courts and tribunals from which it was drawn). The law merchant, for example, was absorbed by the common law in this way — compare, for example, Edie v East India Company (1761) 2 Burr. 1216 (97 ER 797) and Pillans v Van Mierop (1765) 3 Burr. 1663 (97 ER 1035).

- It has been said for example that equity and restitution both evolved to fill gaps which existed in the rest of the law — note the observations of Gummow J in Roxborough v Rothmans of Pall Mall Australia Ltd (2001) 208 CLR 516, at para [75].

- See, for example, the observations of Deane J. in Thompson v The Queen (1989) 169 CLR 1, 34.

- See, for example, Lipohar v The Queen (1999) 200 CLR 485, at paras [43] and [44] and John Pfeiffer Pty Ltd v Rogerson (2003) 203 CLR 503, at para [2].

- O. Dixon, Jesting Pilate and Other Papers and Addresses (Collected by Woinarski, Sydney: Law Book Company, 1965), 199.

- Ibid.

Some Historical Comparisons

Some Historical Comparisons  Yet, whether through ‘prudent forethought’ or otherwise, a measure of order was ultimately realised. By the turn of the eighteenth century, trespass and its progenitors (particularly assumpsit and trover) had emerged as the only forms of action in common use within the English common law.8 Active competition for jurisdiction amongst the courts and tribunals which then comprised the divided English legal system had also, by then, had a substantial impact upon the law administered in other jurisdictions.

Yet, whether through ‘prudent forethought’ or otherwise, a measure of order was ultimately realised. By the turn of the eighteenth century, trespass and its progenitors (particularly assumpsit and trover) had emerged as the only forms of action in common use within the English common law.8 Active competition for jurisdiction amongst the courts and tribunals which then comprised the divided English legal system had also, by then, had a substantial impact upon the law administered in other jurisdictions. The emergence of the maritime lien as the mainstay of the general jurisdiction in admiralty provides a useful example of how a largely uncontentious co-existence was eventually achieved between two otherwise conflicting jurisdictional streams.

The emergence of the maritime lien as the mainstay of the general jurisdiction in admiralty provides a useful example of how a largely uncontentious co-existence was eventually achieved between two otherwise conflicting jurisdictional streams. A need for coherence in the law has in recent years proven influential in the disposition of a number of marginal cases in which litigants have sought to extend general law concepts and principles beyond their established bounds. In 2001, for example, in the matter of Sullivan v Moody,29 the High Court was called upon to consider whether a common law duty of care might be owed by those responsible for investigating and reporting upon cases of alleged child abuse to those suspected of having committed the abuse. A unanimous bench denied the existence of any common law duty of care in those circumstances out of an expressed concern for ‘… the coherence of the law’.30 In another matter more recently determined by the New South Wales Court of Appeal, one of the grounds upon which that court denied the existence of a common law duty of care on the part of a governmental employer to conduct its disciplinary procedures so as to avoid psychiatric harm to an employee was an expressed concern that the imposition of a duty of that kind would give rise to issues of compatibility and coherence between the law of tort, on the one hand, and statute, contract and administrative law, on the other.31

A need for coherence in the law has in recent years proven influential in the disposition of a number of marginal cases in which litigants have sought to extend general law concepts and principles beyond their established bounds. In 2001, for example, in the matter of Sullivan v Moody,29 the High Court was called upon to consider whether a common law duty of care might be owed by those responsible for investigating and reporting upon cases of alleged child abuse to those suspected of having committed the abuse. A unanimous bench denied the existence of any common law duty of care in those circumstances out of an expressed concern for ‘… the coherence of the law’.30 In another matter more recently determined by the New South Wales Court of Appeal, one of the grounds upon which that court denied the existence of a common law duty of care on the part of a governmental employer to conduct its disciplinary procedures so as to avoid psychiatric harm to an employee was an expressed concern that the imposition of a duty of that kind would give rise to issues of compatibility and coherence between the law of tort, on the one hand, and statute, contract and administrative law, on the other.31  The natural development of the general law may also be affected by statute, and by the need to ensure coherence with statutes. In Johnson v Unisys Limited,37 the House of Lords rejected the appellant’s claim for common law damages for unfair dismissal on the ground that a newly developed common law right of the kind contended for would cover the same ground as rights which had been expressly provided for by statute. As Lord Hoffmann explained:

The natural development of the general law may also be affected by statute, and by the need to ensure coherence with statutes. In Johnson v Unisys Limited,37 the House of Lords rejected the appellant’s claim for common law damages for unfair dismissal on the ground that a newly developed common law right of the kind contended for would cover the same ground as rights which had been expressly provided for by statute. As Lord Hoffmann explained: Conclusion

Conclusion