FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 102: December 2025, Regional Bar

The new courthouse, 1975

Fairness, like beauty, lies in the eye of the beholder[1].

The best years of our lives are often spent in pursuit of income. Yet in the justice system, we also give ourselves to a higher purpose – serving the community through fairness, justice, and the steady hand of the rule of law.

In courthouses across the state, justice demands more than skill and strategy. It requires a willingness to step into the darkest of human stories. Because the impact of crime does not end with the act itself. It lingers in shattered lives, traumatised families, and the legal processes that follow.

This year, we celebrate not only the Townsville courthouse as a building, but the extraordinary contributions made to justice and the community within its walls. The colourful characters, the stalwarts, the steady hands on the bench who have guided the flow of trials, given voice to the vulnerable, and ensured every party receives a fair hearing.

Completed in 1975 after years of lobbying, the new courthouse was so long promised that retired Justice R.J. Douglas – the former Northern Judge of the Supreme Court – responded to the announcement with: “I don’t believe that.”

The old wooden courthouse building had been blown up, struck by a cyclone, riddled with holes in the floor, and eventually burnt down. Shockingly, it had no air-conditioning. Judge Finn, then a prosecutor, owned what was thought to be the oldest wig in Australia, held together with glue. He refused to buy a new one, insisting the government should provide the tools of his trade. When a visiting Brisbane judge kept his wig on in court, Finn was forced to follow suit. As the heat rose, the wig melted. Glue slid down his face, and the remains fused to his head.

The old courthouse, 1962

The current Townsville Courthouse is a remarkable structure, influenced by the Japanese Metabolism movement. Coral-inspired facings reflect the local reef. Designed by Ray Smith[2], of Hall, Phillips & Wilson, it won the National Enduring Architecture Award in 2018. The interior was purpose-built with significant input from Justice Skerman, another former Northern Judge. It harbours forward-thinking design: bar tables angled to provide equal access to judge and jury; and a female robing room – small, yet generously fitted with lockers.

Today, the building houses the Magistrates, District and Supreme Courts, together with QCAT and the Land Court. And, on occasion, it receives filings from sovereign citizens – though, true to form, they often “don’t believe that” either.

Supreme Court One is a majestic courtroom, designed to dispense justice in the most solemn of cases. High ceilings, an interior balcony, and an entire wall of square windows connect participants to the vast North Queensland sky, a reminder that life is bigger than the moments inside. It has been the centre of hundreds of murder trials, the gallery often peopled with family and friends – lost sons and daughters invisible, yet never forgotten.

On 24 October 2025, Court One hosted the fiftieth anniversary ceremony, attended by a who’s who of the local legal profession, the judiciary, and the Attorney-General. Yet back in 1993, that same courtroom was occupied by a twenty-year-old woman watching the trial for the murder of her twin brother. Two flatmates, Cowburn and Fulford, accused of bludgeoning him to death with a rock as he slept. Those moments have faded for most, except the families and friends, and every person involved in that trial. The jurors had two weeks to hear the case, two days to deliberate and return a verdict of manslaughter – not murder – and a lifetime to doubt their decision. Thirty years on, her name, like so many others, remains unspoken.

On the balconies beyond the windows, cigarettes have been smoked and secrets shared. Deals negotiated. Affairs begun and ended amidst the blaze of fifteen-hour workdays. Grief, heartbreak and triumph. Grand characters have graced its interiors[3]. Mark ‘Sludge’ Donnelly, of the Townsville Bar from the 1980s to the 2000s. He fired legal arguments at the bench, his throat a powerful machine gun of logic. He once bought an entire jury a beer after they acquitted his client. Sludge, a central figure in the ‘raspberry fuzzberry’ scandal – drinking the cocktail bought for him at the Exchange Hotel by a juror, this incident later emerging in the evidence at a subsequent retrial.

Courtroom One is the second home of barrister Harvey Walters. Trusted and reliable. Prominent in so many major murder trials: MacQueen and Peel, Farr Scrivener and Hills. His address in the Rachael Antonio case has become the stuff of legends. No body had been found: Walters told the jury they could not even be satisfied she was dead. At that moment, a woman with a stunning resemblance to Rachael entered the gallery. A collective gasp. Could it be? She sat quietly – a work experience student. Not Rachael, but the point had been made.

Many competent prosecutors have worked Courtroom One: David “Moggy” Meredith, James “Jim” Henry SC (now Justice Henry), Justin Greggery KC and others. Competent, diligent prosecutors. Patiently guiding juries to the truth, through the maze of misdirection strewn by the colourful cast of defence lawyers.

The Townsville courtrooms have witnessed every kind of drama: the competent lawyer, the reckless lawyer, the acquittal, the high-stakes case. It has been a theatre of human experience, a thrill ride more intense than any film. A small stage, yet vast in its impact.

Judges’ associates, often fresh from James Cook University, are thrust into the intensity of Townsville courtroom trials, riding every emotional wave. One associate, tasked with reading lengthy transcripts to the jury late at night, unconsciously adopted the accents and mannerisms of the colourful barristers she was quoting, amusing the courtroom while keeping the jury informed in the prerecording days, when stenographers typed every word.

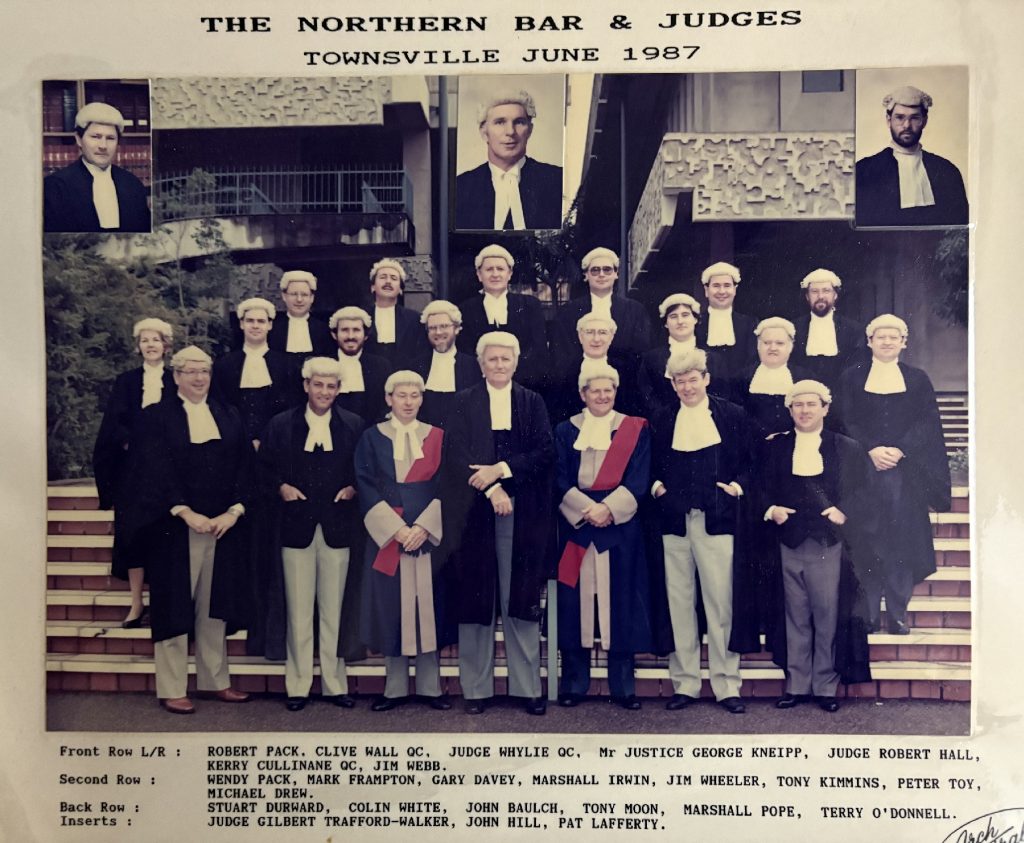

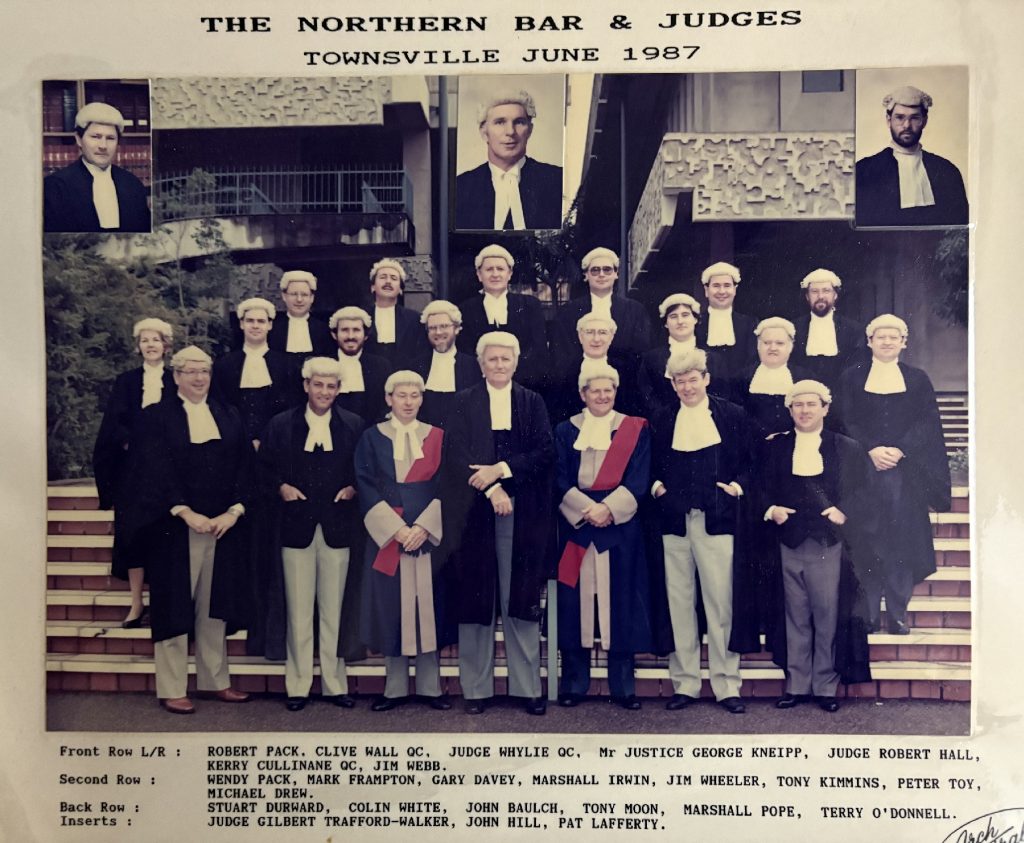

Civil trials are still run in Townsville – medical negligence, workplace injuries, wills and commercial disputes. Specialist lawyers have their own colour: Michael “Swampy” Drew for plaintiffs, wily and strategic; stern insurance representatives frowning as cases turn unexpectedly; and silks such as John Baulch and Stuart Durward, were stalwart in every crisis. The Northern Bar has always been regarded as particularly strong.

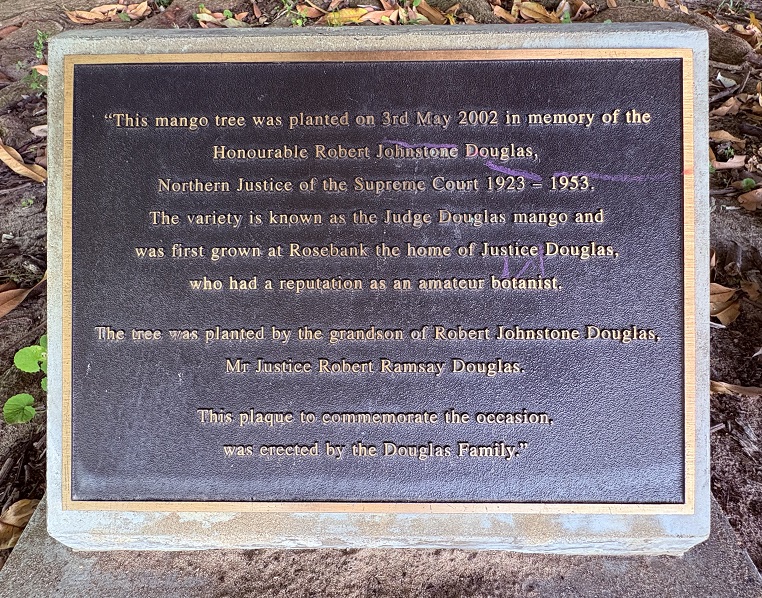

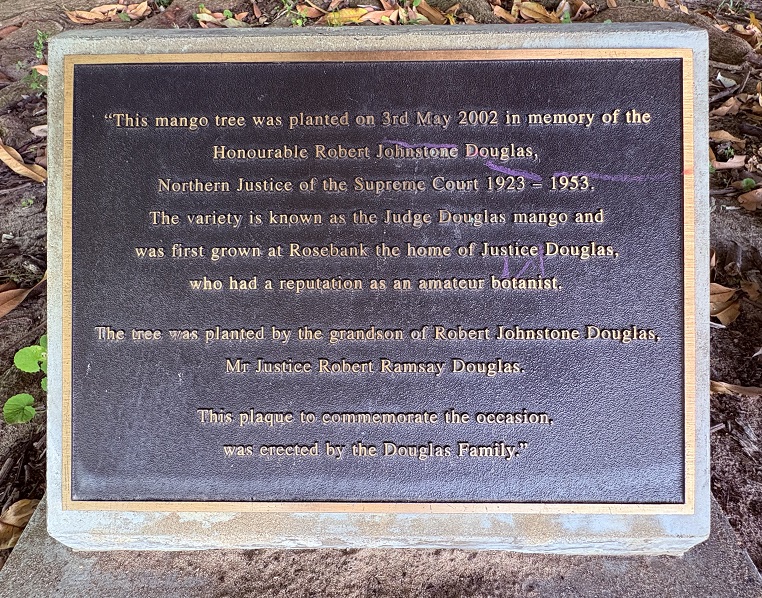

Kerry and Bob planting the RJ Douglas mango tree

Many Judges have come and gone over the last fifty years. The mango tree out the front of the courthouse was planted by then Justices K.A. ‘Kerry’ Cullinane and Robert ‘Bob’ Douglas. The tree itself is a genus created by Justice R.J. Douglas, again, Northern Judge for over forty years and a keen botanist. Cullinane purchased it at market, where it was advertised as the “Judge R.J. Douglas” tree. It bears little fruit but, as Cullinane notes, stands where the innocent and guilty pass equally.

Portraits in Courtroom One capture Justices Cullinane and Sir George Kneipp, successive Northern Judges, dignified in oil as they were on the bench. Kneipp never wore a wig and is famous for his capacity for beer, often consumed at the public bar. He suffered personal tragedy, but continued working with quiet determination – he and Lady Ada lost their daughter, Christine, to an incident at the waterhole in Arcadia Bay on Magnetic Island at Easter in 1966. He passed away soon after his retirement. His ghost is said to haunt the judges’ chambers on Level D. When told about this, Lady Ada said: “That’d be right, if the blighter ever came back, he’d go straight to work.”

Justice Cullinane. What more can you say about a man than that he is a hero to his associates, and loved by his wife and children. Registry staff compiled a history of the Judge when he retired, and on the front they stated: “Kerry, the kind and considerate.”

Judges’ Chambers behind the courtrooms on Levels C and D have a sense of space—wide corridors, rectangular windows evenly spaced for light, and anterooms where associates can gossip while preserving the balance of privacy and access. From Chambers, the view stretches over the legal mean streets below.

One afternoon, Justice Cullinane asked his associate to call a solicitor, who was late. They stood quietly, side by side, watching a suited figure charge down Walker Street—jacket billowing, briefcase flapping. He tripped, suspended in air, arms and legs flailing, then catlike found his feet. By the time he reached court, the Judge simply nodded. No need for apology.

Over the years, eminent Judges have filled the Chambers on Level C. Among them was Judge Kerry O’Brien, a former prosecutor who was to be appointed Chief Judge of the District Court – a fair Judge who enjoyed Bar dinners and the occasional sing-along. Judge Pack QC, an icon at the bar and then the bench, with his keen intellect, low booming voice, understanding of life out West, and zero tolerance for dangerous drivers.

Then there was Judge Clive Wall QC (now KC), formerly of the local Bar, who brought his unique flair to the bench. A straight shooter with a penchant for sharp wit, he lunched in style, wore short-sleeve business shirts from Best and Less, and played a fierce game of lawn bowls. He had little patience for fools or cowards, and in Court, he led from the hip.

Northern bar and Judges 1987

Some lawyers viewed an appearance before Judge Wall as a walk in the lion’s den. But the better ones saw an opportunity. His directness laid out every concern, giving them the chance to address each point – and, with enough skill, steer him—sometimes reluctantly, metaphorically kicking and screaming – towards the outcome they sought.

Then there’s Judge Greg Lynham, graduate of James Cook University, who was a popular President of the JCU Law Students’ Society[4]. He is a former train driver, and an Anglican Priest, which perhaps explains his unflappable nature. He practised at the Townsville Bar before his appointment to the Bench, where he continues to keep proceedings on track.

The District Court in Townsville has seen its share of complex and often harrowing cases over the last fifty years. A paedophile ring uncovered in an otherwise quiet suburb—an unimaginable honey trap that lured vulnerable foster children into drugs and exploitation. And the soldier thirty years ago who smashed his twin babies heads together, leaving both brain-damaged. Convicted of grievous bodily harm, his sentence has long been served. But those babies, now adults, and their mother, are still serving theirs.

This is the grim reality of life in the Townsville Courthouse. We cannot turn back time and undo the damage. We do not fix things. Our justice system has no magic wand, much as we might wish. What we can offer is a steadfast commitment to the rule of law, a fair hearing, and just consequences in accordance with the rule of law.

But even as we uphold these principles, gaps remain. Fifty years ago, Justice Skerman ensured fair provision of services for women lawyers in the Court. Yet, despite these efforts, no woman has ever been appointed as a sitting Judge in Townsville.

Across the landing from the District Court, the Magistrates’ Courts on Level B plays a critical role in the Townsville justice system. While their connection to the broader judicial landscape is less visible, magistrates hear ninety-five percent of all cases in Townsville[5].

Level B is where the full circle of criminal life unfolds. Like Rumpole of the Bailey – who knew the Timmins family better than they knew themselves – magistrates often come to know local families intimately. Newborns enter the child protection system – some with foetal alcohol syndrome, others abandoned in shopping centres or forgotten in showers. Their parents, weighed down by drug or alcohol addictions, repeatedly appear in magistrates’ courts – for tenancy disputes, theft, drugs, domestic violence, and complaints about vicious dogs.

As the children grow, their offences escalate – shoplifting, break-ins, stolen cars. Occasionally, later comes robbery, rape, or murder. Time in jail often morphs the offending into domestic violence and public drunkenness. Eventually, these offenders wear out, winding down with public nuisance charges on Level B before fading from the system altogether, far older than their years.

One of the first trials I observed as associate to Justice Cullinane involved a 17-year-old indigenous teenager from Palm Island, charged with murder. He shot someone in the street, accusing the dead man of being a paedophile. I never really knew if the accusation was true. He was convicted of manslaughter and served a seven-year sentence.

Twenty-five years later, I sat as a Magistrate in the same courthouse – except now, two floors lower. The teenager, now fully grown, appeared on videolink from the same prison where he had served his sentence. His criminal record had evolved, now including multiple convictions for paedophilia. His life is a stark reminder of the circle of crime that repeats itself through the generations.

And it begs the question: in the decades to come, how many of his victims will walk through these same old courthouse doors, and embark on a similar journey?

It is not just lawyers who’ve given their best to this Courthouse. Volunteers like Salvation Army Officer Bob Downs – now in his nineties – have been at the front desk for more than forty-five years. Anne Frankcom, whose portrait hangs on the front desk, supported domestic violence victims from the early 1990s – long before government services were available.

On the landing between courts, security guards work hard to keep everyone safe – scanning, searching, checking. But for most of the courthouse’s history, that landing was a different place. There were no checks. Security used to be a retirement job, with elderly guards passing the time doing crosswords. Occasionally, someone would be reprimanded for leaving a cigarette butt on the walkway. Once, a man snatched a gun from a police officer in the magistrates’ court and escaped, waving it around in the foyer before bolting. We talked about it for weeks. We didn’t want more security, just fewer guns. Defendants would wander in and out, dressed in their finest. Now, you’re lucky to get a collared shirt. The courthouse has evolved with society.

The District and Supreme Court Registry in Townsville has been a centre of excellence for fifty years. Competent, polite, and efficient, the staff have seen it all—article clerks dashing in with documents that needed filing yesterday, assisting the Registrar to collar jurors on the street when there weren’t enough to fill the panel, serving legal process to people on ships. Long-serving members like Phil Green – who has worked there for forty-five years – Rita Green, Katina Argyros, Robin Wegener, Lisa Dyke, and Angela Blackford have been the backbone of this operation.

Jenny Dawson, who cleaned the courts for over forty years, was a quiet presence until she retired.

1992

Brian Hooper, the Supreme Court bailiff for many years, was exemplary – only once did a juror escape on his watch. The jury were seconded at the Sugar Shaker. After midnight, one juror was spotted by police in The Bank nightclub. The juror bolted back to the hotel and ran around the jury floor (an unbroken circle), trying to evade police. Brian sat still and got his man, but it was an expensive night for the government – they had to fund a retrial.

On the magistrates’ registry side, the workload is relentless. Staff come and go like the rolling tide, but there are the stayers who have kept the place afloat over the last fifty years – Kerry Christopher, Judy Stagg, Hilda Wilson, Debra Shibasaki, Ellen Brown, Graeme Evans, Brendan Moule, Susie Warrington (now magistrate).

On the ground floor, bailiff Ian Kennedy has been on duty for thirty-seven years. Once with his own office, now his desk is under his hat on the first floor. His unflappable nature and amused smile are his best tools of enforcement. When he says the court process has been served, you can rely on him.

Beneath the courthouse, in the cells, police, inmates, Salvation Army chaplains, lawyers, and nurses work tirelessly with the never-ending surge of prisoners. Over the past fifty years, watchhouse keepers have played a vital role in ensuring safety and order, overseeing the flow of detainees – from meth addicts in withdrawal to children after crime sprees.

This article is a snapshot of life in the Townsville Courts over the past fifty years. Many people have been mentioned, but countless others who should have been mentioned have shared the best days of their lives, imparting their knowledge, time and ability with the community of Townsville – barristers, solicitors, magistrates and judges, clerks, security, support staff, cleaners, police, and volunteers – making the Townsville courthouse a place where justice, on balance, has prevailed.

No system is flawless – to err is human. But if the role of a court is to apply the law impartially, free from fear or favour, affection or ill will, then those who envisioned and built the Townsville Courthouse would take pride in its first fifty years.

The RJ Douglas mango tree today

[1] Lord Nicholls, White v White [2000] UKHL 54netny

[2] after attending the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka

[3] Colourful personalities fill the Courtrooms with enchantment.

[4] At the same time I was Editor of the JCU Student Law Society Journal, The Precedent.

[5] https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/courts/magistrates-court/about-the-magistrates-court

The new courthouse, 1975

The new courthouse, 1975

The old courthouse, 1962

The old courthouse, 1962

Kerry and Bob planting the RJ Douglas mango tree

Kerry and Bob planting the RJ Douglas mango tree

Northern bar and Judges 1987

Northern bar and Judges 1987

1992

1992

The RJ Douglas mango tree today

The RJ Douglas mango tree today