FEATURE ARTICLE -

Inter Alia, Issue 100: June 2025

Travels in Sindh – A Glimpse into the Legal System of Pakistan, Karachi, and the Vibe

In light of the recent conflicts between India and Pakistan, it appears the subcontinent is garnering a lot of attention. Given the interest, I thought I would write about a less pugilistic aspect of Pakistan (but only slightly so): its legal system.

In April last year I travelled to Pakistan with my wife to visit her family. We spent the first two days of that trip in Karachi. It is not a city for the faint hearted, but until it is experienced, judgment should be reserved. Its legal system reflects the frenetic and often overwhelming nature of a city of 20 million.[i]

We are staying with the Rahmans – the legal branch of my wife’s family. Her grand-uncle is Naim Ur Rahman. He lives with his wife, daughter and grandson. His son, Abdur Rahman has recently been appointed to the High Court of Sindh.

Uncle Naim is by the dining table, having returned from work when we first meet. He is a little hard of hearing and his knees are – to use his words – “wretched”, but his mind is still as sharp as ever. He is nearly 89 and still practises three days per week at the large corporate firm Vellani & Vellani.

Like many lawyers in Pakistan, Uncle Naim studied abroad, in England. He read law at University College London, before his call to the bar at Inner Temple in 1961. It is common for those with the means to do so to study in the UK and join one of the four Inns before returning to Pakistan to commence practice. Today the University of London has established a campus in Lahore – “Universal College Lahore” – to allow students an opportunity to obtain an English degree locally.[ii]

Pakistan’s legal system is fused, and all lawyers are simply referred to as “advocates”. Robes and wigs have gone too, except for judges who wear an open gown over their suits.

However, remnants of Pakistan’s colonial past persist in what is to a large extent a common law legal system.[iii] Moreover, those who are members of one of the four Inns will often style themselves as “barrister”, effectively using it as a substitute for “Mr” or “Ms”. Judges of the High Court (equivalent of our Supreme Court) are referred to not as “Your Honour” but “My Lord”.

In place of wigs and gowns is the “lawyer’s uniform”. Men must wear a black suit with a white shirt, a black tie, and black shoes. In Sindh, men are allowed to wear white tabs instead of tie. Men can wear white trousers if they wish, but during my brief visit to the High Court, Uncle Naim was the only one I saw doing so. The inference is that so long as everything is black and white, there’s no issue, but black tie and trousers are the status quo and what is worn by almost all advocates.

The equivalent for women is a white shalwar kameez,[iv] dupata (scarf), and a black jacket.

The dress-code for men and women is strictly enforced. A few months before I arrived, a lawyer was suspended from practice for three months. He had failed to wear a black tie after being warned by the presiding judge that he was not dressed properly.[v] A two judge bench dismissed the lawyer’s appeal, stating, “the learned counsel was directed to make correction in his uniform by wearing ‘black tie’ as required under the aforesaid Rules and refusal for doing so translated into slapping of the suspension and again when the matter was fixed for recalling of the suspension, the counsel was directed to tender an apology for his behaviour, but not doing so, continued with the suspension, this egoistic behaviour in Court does not call for any leniency”.[vi]

I had already learnt from my wife that lawyers are fiercely protective when it comes to their “uniform”. They’re also rather litigious about it. Many waiters working in hotels and restaurants dress as lawyers do – black suit, white shirt, black shoes, black tie. This is much to the chagrin of some of the country’s advocates.

In 2015 the Punjab Bar sought an injunction to restrain waiters from being allowed to wear a black suit and a black tie. The claim was dismissed, as Justice Ayesha Malik remarked “the court could not issue directions on what citizens could or could not wear”. Three bar councils issued warnings to waiters in 2021 in similar terms, which had, as far as my research could find, little effect.[vii]

Uncle Naim and I chat for a while about this and other matters. He quizzes me on whether I know the difference between a court of law and a court of justice. I admit defeat and that I do not. He then tells me that his son will be home from Court soon, probably by lunch. When Naim began practice, courts would run until 4.00pm or even later, just as they do in Australia. However, he tells me, lawyers (and particularly their wives) grew upset at the long hours lawyers spent in their offices doing paperwork after court. Eventually the court changed its sitting times.

Generally, the Sindh High Court sits until around 1.30pm. That period is truncated until around 11.30am on Fridays to accommodate the observance of Friday Prayers. [viii] Lawyers then spend the last hours of the day catching up on paperwork before returning home at a reasonable hour. Justice Abdur Rahman – affectionally known in the family as “Bhai”, meaning “Brother” – will be home even sooner, despite the fact it’s still the morning.

Our visit coincides with the end of Ramadan, and people expect Eid[ix] to be declared any day now. The timing is uncertain because it requires the sighting of a crescent moon, by a certain time of night by a panel of experts. Everyone knows though that it will be either tomorrow or the day after. Eid itself holds similar significance in the Muslim calendar to Christmas Day in the West. This gives people an extra reason to wrap up early where they can.

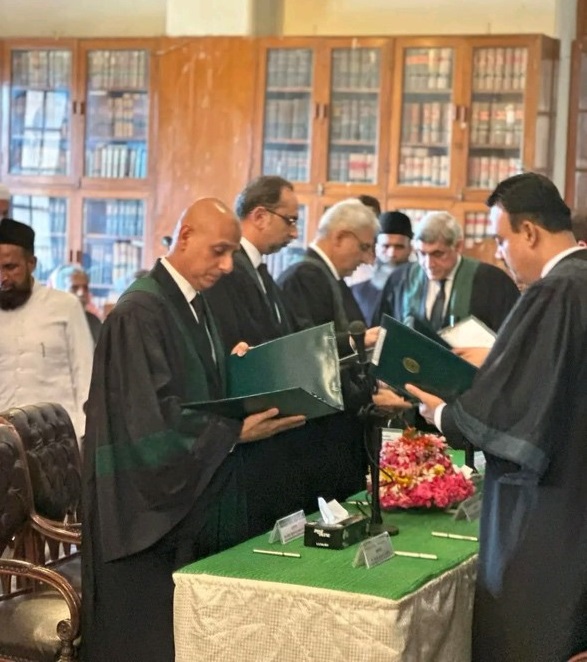

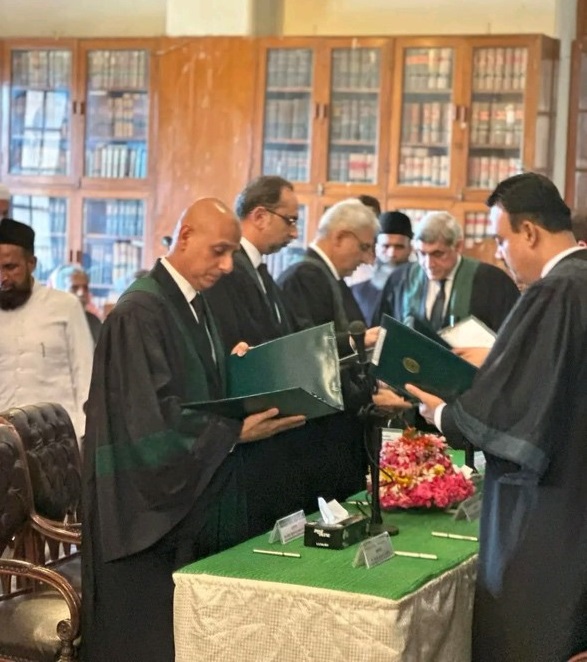

Mr Justice Abdur Rahman (front left) on the day of his swearing in, 2023. Source: The Lex

Sure enough, after a little while I meet Bhai. He comes in the side door and welcomes me to Pakistan. He casts an impressive figure – black suit, black tie, white shirt – braces too; dressed to the nines.

I resist the urge to call him “Bhai” and simply refer to him as “Judge”. My wife explains to him that tomorrow Naim and I will attend the Sindh High Court for me to look around and observe proceedings. “Good God,” he exclaims, curious about why anyone would come so far just to watch Court proceedings. He asks me about the law in Australia and eventually I run out of things to say. Not wanting to be responsible for the death of the conversation, I discuss the first thing that comes to mind – “The Castle”. Despite his prior study in the UK he is unaware of this niche aspect of Australian culture. I describe the notion of the “vibe” and how some lawyers during my time in Darwin described themselves as “vibe lawyers”, relying not on case law or legislation but their own instinct and the “vibe” of the law. The judge finds this amusing.

The next day I don my blackest suit and my whitest shirt: I’d rather not declare contempt in a foreign court on my practising certificate application. I’m grateful for the advice of Vice President O’Connor, to whom I was associate two years prior: “always travel with black tie or at least a suit. You’ll never know when you’ll need it”. It’s probably not the “black tie” he had in mind but thanks to his words of wisdom I’m prepared. Naim gifts me one of his ties, telling me to choose from the rack of about twenty black ties in the cupboard.

The author with Naim in the dining room of his Karachi Home.

Naim’s driver waits for us and we depart for the High Court of Sindh around mid-morning. It takes 20 or more minutes to traverse the hive of traffic on Karachi’s roads. After a few traffic jams and an anti-clockwise trip around a round-about, we arrive at the rear of the Sindh High Court.

The Court Building was constructed in 1923 from sandstone in what was then British India. The front entrance with its grand stairs and neo-classical pillars lies disused. Like Brisbane’s Federal Courts, the entrance to the building is now from the back. I suspect this is simply because it makes security easier to manage. The rear courtyard and parking area is completely fenced with concertina wire running along its length.

Heavily armed police personnel wave us down as we approach a gate. One officer, rifle slung over his shoulder, exits the guard post and holds an inspection mirror under our vehicle. Our driver says something in Urdu to the other guard, after which he peers down into the car and sees Uncle Naim. He nods and motions to the other who retracts the mirror and motions towards the gate. The gate is opened, and we drive through.

We park close to the entrance and I see the courtyard is replete with lawyers. Many are on their phones, speaking frantically and pacing back and forth. Some are in small groups looking at documents. Others strut towards the entrance, files in hand. Almost all of them looked stressed.

Sindh High Court. Source: “The News International”

I’m ahead of Naim, and I pass through the metal detector which goes off. The guard sees I’m with Naim and smiles, muttering thik hai, thik hai (“it’s fine”) and beckons me through. As Naim crosses the threshold both guards stand, one salutes him. Naim seems embarrassed by this. As we turn left and begin down the corridor I ask him why they salute, and if it’s due to his years of experience. He insists that they’re only saluting him because of who his son is. I doubt this as we continue down the corridor and another guard rises and salutes.

The black and white tiled halls echo against the stone ceilings. Everyone mutters softly as voices carry too. Not much seems to have been done by way of renovation since the building’s completion, but it has stood the test of time.

The Sindh High Court is about a century old but it’s by no means crumbling or run down. It seems to have “good bones” and despite its age, or perhaps because of it, conveys a sense of charm.

On our right, at about ten-metre intervals, are the courtrooms. Mid-way between each of the courts are closed doors. Some have a guard seated by them, others don’t. I looked closely at the plaques above and realised that the doors lead into judges’ chambers. Each judge has their plaque above the door, accessible from the main corridor of the court.

It was rather a shock to see chambers so accessible, in stark contrast to all Australian courts with chambers tucked away on a higher floor. However, no one seemed particularly bothered by this layout, and Naim explains that’s simply just the way the British built it.

We peer into one of the courtrooms. Two judges preside over what appears to be something analogous to the applications list. It is common for two judges to preside in many matters. The courtroom has beige walls and ornate timber fittings. Bookcases filled with law reports line the rear wall. About 20 lawyers sit in the gallery waiting for their matters to be called on.

No coat of arms adorns the space above the bench. Instead, there is a photo of Pakistan’s founder – Mohammad Ali Jinnah that has replaced a picture of the regent of the British Empire. Jinnah is referred to through the country as Quaid-e-Azam or The Great Leader. He commands special significance in legal circles as he himself was a barrister, joining Lincoln’s Inn in 1893 and being called to the Bar in 1896.[x]

Proceedings are in English, as are judgments. Different provinces have different rules regarding whether English or Urdu is the status quo. It can also vary depending on whether the matter is criminal or civil in nature. In Sindh – at least in civil matters – English seems to reign supreme. The rules of the Sindh High Court prohibit reception of documentary evidence unless it is either in English or has an English translation.[xi]

This practice has not gone without criticism due to what is perceived by some as classism and a colonial hangover.[xii] Nevertheless, one of the judges explains to an advocate in very, very, very clear English the great difficulty he is having with that advocate’s argument.

After a few minutes Uncle Naim whispers that we’ve seen enough. We move further down the corridor until we come to Bhai’s chambers. A guard stands up, salutes and lets us in. Bhai is sitting at the far end of the chambers on one of the sofas. Another judge is with him. I learn this is Mr Justice Muhammad Faisal Kamal Alam.

Justice Alam has an impressive legal background, practising both in Pakistan and the UAE before going to the bench. Like Naim and Bhai, he is/was an “Advocate of the Supreme Court”. Pakistan has an equivalent of King’s counsel, “Senior Advocate of the Supreme Court”. However, becoming a “Senior Advocate” requires the advocate to first be an “Advocate of the Supreme Court”. That in itself contains a number of steps and is an achievement.

A newly minted advocate in Pakistan does not have a right of appearance in all courts. For the first two years they are limited to the lower courts, effectively the Magistrates Court equivalent. At the two-year mark they may apply to enrol as an advocate of the “High Court” of their province, for instance Sindh province (where Karachi is the capital) or Punjab (where Lahore is the capital) etc. They then have a right of appearance in the High Court. After seven years or so practising as an “Advocate of the High Court” a lawyer earns the right to apply to be an advocate of the Supreme Court.

The stepping stones to achieving the “Supreme Court Advocate” status imports bragging rights among some of the Pakistan’s lawyers. To my surprise and mild amusement, it is commonplace for lawyers to have plaques above or below their vehicle number plates displaying that they are an advocate, or an advocate of the High Court or even Supreme Court.[xiii] This has been met with criticism in the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) with one judge – speaking extra-curially – suggesting they were illegal.[xiv] It is hard to imagine members of the Queensland or interstate Bars putting “barrister” above their number plates. I’m not sure how that would go down with members of the public.

What I observed from three weeks in Pakistan across three cities, Islamabad, Karachi and Lahore, was countless vehicles (and even a few motor-bikes) with the custom numberplate or plaque. They seemed to be particularly common in Lahore. However, despite their ubiquity, having an “Advocate” number plate didn’t appear to garner much favour among other motorists. In fact, if anything it was the opposite.

As I sit down Bhai introduces me to Justice Alam and, to my surprise, informs me they have just been discussing the “vibe”.

“We find this concept quite interesting,” he recounts. The two judges have been sitting together earlier that morning over applications, and inform me that the “vibe” is something they often observe in their courts, but until now hadn’t been able to put it into words.

Earlier that morning they had a matter where a lawyer turned up to court without his file, and was unable to confirm with the court whether he was appearing for the petitioner (applicant) or respondent. There are a lot of matters like that, they tell me. It slows down an already stretched system to the point where the backlog of judgments seems almost insurmountable.[xv]

I tell them about Queensland’s Vexatious Proceedings legislation and our mechanisms for summary and default judgment. They would be handy at times, they tell me, but ultimately a drop in the ocean. Justice Alam informs me that vexatious litigants aren’t the problem, nor are claims with no reasonable prospect of success. It’s a sheer “numbers game”. The cases simply comprise, almost overwhelmingly, of people with triable claims who just need to have their day in court. All the judges can do is simply work hard to ensure the petitioners, many of whom are poor and disadvantaged, have their day in court.

Later that day, at dinner, I learn from Bhai that he does not have the luxury of being able to issue ex-tempore judgments. He writes and publishes all his decisions, even, it seems on applications. Since his appointment in early 2023, he has disposed of around 2000 matters. Granted, some of them are brief, but the sheer number of cases is staggering. He also does not have an associate; he is to bear the burden of drafting, proof-reading and editing alone.

We discuss the nuances of Pakistan’s legal system. At its core, it is a common law system. Elements of Islamic Sharia are woven into the legislation, generally where the Islamic law will conflict with the common law. We “don’t have constructive trusts here” Bhai tells me, “as it has all been codified. we simply have ‘trusts’. But there’s an Islamic concept of ‘Waqf’ which is analagous”. There is also a Federal “Shariat” court which moderates and oversees new laws to see whether they are “repugnant to the values of Islam”.[xvi] It has the backing of the Constitution and has the power to declare laws Un-Islamic and effectively void.

Nevertheless, the remnants of English law are seen frequently, and the large number of students studying at English universities probably reinforces this.

Finally, we talk about the best evidence rule, which, Bhai assures me is alive and well in Pakistan. “I applied that rule in a case just last week,” he tells me excitedly.

By the time we leave Karachi I am left with the distinct impression that despite Pakistan’s occasional dubious reputation in the West – coupled with its litigious lawyers protective of black suits and white shirts – it comprises many hard-working and devoted advocates, committed to the advancement of justice in a country where many are born disadvantaged and have the cards stacked against them.

I suspect many Pakistani judges, like in Australia, make a significant financial sacrifice in accepting a judicial appointment, but are happy to do so out of an abiding obligation of service to the community at large. Bhai loves his job and wouldn’t be happy doing anything else. Uncle Naim continues to work, and, like most barristers, will probably never stop.

Author: Nicholas was called to the bar in May 2025 and is a reader with Denning Chambers. The author is greatful to Justice Rahman for his feedback on this article.

[i] Commissioner Karachi, Census data https://commissionerkarachi.gos.pk/population

[ii] Universal College Lahore, https://ucl.edu.pk

[iii] An article in Pakistan’s popular paper “Dawn” that was published in late 2023 can be found here. It criticises the judicial system for a number of reasons, including, principally, its alleged deference to its colonial past https://www.dawn.com/news/1787151

[iv] Shalwar Kameez is unisex type of clothing in Pakistan comprising trousers and long sleeve shirt with the front and back of the shirt coming down to around the knees.

[v] Muhammad Aktar Khan v Registrar, High Court of Sindh & Ors D-752 of 2024.

[vi] See also Sindh Legal Practising and Bar Council Rules 2017.

[vii] https://images.dawn.com/news/1186868/pakistans-lawyers-turn-fashion-police-tell-waiters-to-stop-wearing- their-uniform

[viii] The High Court of Sindh, 24 March 2022 (Sitting Hours) https://sindhhighcourt.gov.pk/news_notifications/source_files/Timings_ramzan_2022.pdf. See also for times outside of Ramazan https://www.sindhhighcourt.gov.pk/news_notifications/source_files/notification_%20office_timings_260917.pdf

[ix] Eid is the day which comes immediately after the end of the month of Ramadan. It is a celebration and denotes the end of the obligatory fastin period.

[x] The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, “Into the Archives: Mohammad Ali Jinnah” https://www.lincolnsinn.org.uk/library-archives/tales-from-the-archive/into-the-archives-mohammed-ali-jinnah/

[xi] Sindh High Court Rules r 286.

[xii] https://www.dawn.com/news/1787151

[xiii] Numberplate image sources: (1) Propakistani.pk “Advocates finally learn a lesson on illegal numberplates”; (2) Faisal Sherjan (Twitter) 25 April 2022.

[xiv] Pakwheels.com, “writing advocate on number plates is illegal, says IHC judge” https://www.pakwheels.com/blog/writing-advocate-on-number-plates-is-illegal-ihc-judge/#:~:text=Justice%20Tariq%20Mehmood%20Jahangiri%20of,certificates%20were%20distributed%20among%20lawyers.

[xv] Dawn, “Over two million cases pending in courts across country”, 13 July 2022, https://www.dawn.com/news/1699337#:~:text=The%20Sindh%20High%20Court%20disposed,pendency%20stood%20at%2044%2C703%20cases

[xvi] https://www.federalshariatcourt.gov.pk/en/objective-and-functions/

Mr Justice Abdur Rahman (front left) on the day of his swearing in, 2023. Source: The Lex

Mr Justice Abdur Rahman (front left) on the day of his swearing in, 2023. Source: The Lex

The author with Naim in the dining room of his Karachi Home.

The author with Naim in the dining room of his Karachi Home.

Sindh High Court. Source: “The News International”

Sindh High Court. Source: “The News International”