FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 34 Articles, Issue 34: April 2009

I am very pleased to add my welcome to Chief Justice French to this jurisdiction, on his first visit in his capacity as Chief Justice of Australia.

I am very pleased to add my welcome to Chief Justice French to this jurisdiction, on his first visit in his capacity as Chief Justice of Australia.

Major anniversaries inspire reflection on the past, and forecasts of the future. This year we celebrate 150 years of good government in this State. That government embraces the work of the third branch, the judiciary.

I am pleased to have the opportunity, today, to affirm the work of the judicial branch of government, especially as this year marks the 50th anniversary of the District Court, and in two years time, we will in 2011 mark the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court.

I wish to speak in this sesquicentenary year of the role of the Supreme Court in particular, in the public life of Queensland.

But before going further, I acknowledge the courts’ high dependence on the support and professionalism of the Bar. In Zeims’ case (1957) 97 CLR 279, 298, Sir Frank Kitto spoke eloquently of the particularly close relationship between the Court and the Bar, observations I repeated at the Christmas Greetings ceremony in December last year. I also then noted the dramatic expansion of the Queensland bar over the last decade, from about 500 barristers to almost 1,200, a prospect that would have dismayed our first barrister, Ratcliffe Pring, on his arrival here in April 1857. Our bar remains notable for its ethical commitment and professional proficiency, of which the courts and the public are the beneficiaries. The Supreme Court’s performance over that decade, and over preceding decades, would have been much diminished absent the assurance of the bar’s support.

And the Bar would have been diminished absent the cohesion engendered by our host, the Bar Association of Queensland, which annually succeeds in convening the best attended bar conference in the nation. The Association reaches its 106th anniversary this year. Its insignia helpfully remind us of the goals and traits which characterize both bar and court, while acknowledging the public orientation of both.

And the Bar would have been diminished absent the cohesion engendered by our host, the Bar Association of Queensland, which annually succeeds in convening the best attended bar conference in the nation. The Association reaches its 106th anniversary this year. Its insignia helpfully remind us of the goals and traits which characterize both bar and court, while acknowledging the public orientation of both.

The Association’s insignia incorporate the Queensland State badge, a light blue Maltese cross with St Edward’s crown at the centre, embellished by a contemporary representation of the scales of justice. There we see symbolic confirmation of actual adherence to enduring traits: the Maltese cross signifying courage; the crown of St Edward the Confessor — benign justice and incorruptibility; and the scales of justice, the rendition to any litigant of what is due, no more, no less. I do not use the word “rendition” in its regrettably contemporary sense.

Let me now speak for a little while about the Court.

It is generally accepted that the Supreme Court of Queensland dates from 7 August 1861. That was the date of assent to the Supreme Court Constitution Amendment Act 1861. The inauguration of the Court was therefore significantly close in time to the date of establishment of Queensland itself, which occurred on 6 June 1859 with the separation of the colony of Moreton Bay, to be named Queensland, from the colony of New South Wales. Of course it was with federation that the colony became a “State”, on 19 January 1901.

I describe that proximity in time between separation and the establishment of the Court as ”significant”, because the early establishment of the Court betrays a view, on the part of our then leaders, of the need to have in place quickly a superior court, in the technical sense, of plenary jurisdiction.

There was also, however, the circumstance that Queenslanders had been but poorly served by the irregular attendances of the New South Wales Judge earlier designated to attend to local needs, Mr Justice Samuel Milford (cf Ross Johnston: History of the Queensland Bar (1978) p 3). A rather indifferent portrait of Milford hangs in the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Sydney, and a copy in the Judges’ Conference Room in Brisbane.

Over the four months immediately prior to separation, the then resident Moreton Bay Judge, Mr Justice Lutwyche, had worked with great dedication. But that early history of the Court was somewhat marked by the turbulence of Lutwyche’s relationship with the government of the day. Fine portraits of Lutwyche and his wife hang in the Supreme Court’s historical precinct, on loan from the Queensland Art Gallery.

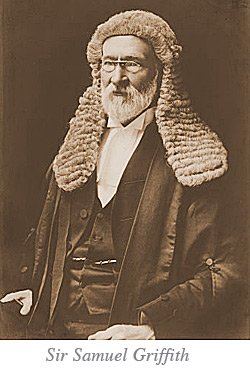

Our historical perspective of the Supreme Court tends to lionize the legendary leadership of Sir Samuel Griffith. His monumental, even Olympian, contribution cannot, however, be allowed to obscure the fact that the first Chief Justice was Sir James Cockle, credited with restoring harmony to the relationship between the Supreme Court and the government, by quelling a turbulent Lutwyche. Cockle was a person, you may recall, who was also able to discover lyrical aspects in algebraic equations. I commend Dr John Bennett’s biography in the “Lives of the Australian Chief Justices” series.

Our historical perspective of the Supreme Court tends to lionize the legendary leadership of Sir Samuel Griffith. His monumental, even Olympian, contribution cannot, however, be allowed to obscure the fact that the first Chief Justice was Sir James Cockle, credited with restoring harmony to the relationship between the Supreme Court and the government, by quelling a turbulent Lutwyche. Cockle was a person, you may recall, who was also able to discover lyrical aspects in algebraic equations. I commend Dr John Bennett’s biography in the “Lives of the Australian Chief Justices” series.

Cockle’s portrait, donated by his granddaughters to the Queensland Library Foundation, hangs behind the bench and the presiding judge’s seat in the Banco Court in Brisbane: it was a generous and greatly appreciated donation, although the granddaughters were said not to have been too upset in parting with the portrait, because gazing at Cockle’s rather ethereal appearance made them feel somewhat uneasy.

Cockle was one of a number of Chief Justices who have over the 147 year history of the Supreme Court displayed courage and independence in supporting and upholding the Court in its conjunction with executive government, into times as recent as those of my immediate predecessor John Macrossan.

I mentioned the inadequate servicing from the colony of New South Wales in the early days as context for the conclusion that Queenslanders were always determined to have their own pivotal institution up and running as soon as possible, casting off as soon as may be any hegemonic dependence on others. A passion for independence is embedded in the Queensland DNA.

It was in this context a delight last August to have the opportunity to edit the Australian Law Journal and with relish to remind the national profession of the important place of our Queensland Courts in the federal constellation.

And so the Supreme Court’s sesquicentenary will follow closely upon the State’s. I was recently bold enough to assert that the people of Queensland have great confidence in the working of their courts. That followed a suggestion from elsewhere that it might be worthwhile establishing a sentencing advisory council. My published claim that there was no clamour for reform of the criminal sentencing process unsurprisingly provoked one citizen to send me a less than complimentary email: but only one, and I note that the “Courier Mail” published a couple of letters expressing substantial confidence in the work of the courts. There is an abiding public respect for the work of our courts.

The confidence is fed by two features, transparency and predictability. That generally so few members of the public take the trouble to come and watch the courts in action does not, I think, signal any broad lack of interest. The inference, rather, is that the courts can be trusted to discharge their responsibility properly, with the ultimate assurance resting in the independence of the judiciary. There is also assurance in the circumstance that if the primary judge is thought to have erred, the result may promptly be rectified on appeal.

Those features of transparency and predictability largely account for the resilience of the courts, a resilience which has characterized our Supreme Court throughout its history. That resilience is occasionally thrown into vivid relief by so-called high profile cases, and comparatively recent proceedings in relation to rapes at Aurukun come to mind. Long term public confidence in the Supreme Court was not dented by those cases: the people accepted their course illustrated the healthy operation of the rule of law.

The long history of the Supreme Court has been sprinkled with controversial cases which have at times provoked not inconsiderable passion. The 1920’s were especially colourful in that respect. Yet none has led to major change in or reform of the institution of the Supreme Court.

We are indebted to the Westminster tradition for the way in which our courts have always discharged their charter of delivering justice according to law, and we must be rigorous to ensure that, as the Supreme Court progresses beyond 2011, we can continue to proclaim those two features, transparency and predictability, as the hallmarks of its independent work.

As to transparency, this jurisdiction remains distinctive for two particular features — the comparative infrequency of suppression orders not mandated by legislation, and comparatively unrestricted public access to court files. I am personally concerned and motivated to preserve that position, notwithstanding pressures for national uniformity, which if followed would erode the high level of transparency we have been able to guarantee in this State because of our approaches in those two respects.

Principle confronts an anathema if we countenance conducting court proceedings in private except where indubitably necessary; and likewise, if we suffer what would ordinarily be condemned as denials of natural justice, except with patent justification. Whether considerations of national and international security have sufficiently justified some recent departures, departures which would otherwise be considered erosions of the cornerstone of our judicial system, is a matter for continuing serious debate. The authority of the judgments of our courts, central to the good government of the community, depends on public confidence in the process, and that vitally assumes transparency and accountability.

It is my contention that our Queensland people confidently assume the reliable independence of its judicial officers, instilling faith in the workings of the courts, notwithstanding that most of the work accomplished in the courts passes without notice. As I have said, that the people do not, by and large, trouble to attend court proceedings, does not signal any general lack of interest, or any lack of appreciation of the significance of the courts — although unfortunately not too many people manage to get their heads around the detail of the process.

In his foreword to then Mr Justice McPherson’s history of the Supreme Court, Sir Harry Gibbs observes:

“In a democracy, every educated citizen should have an understanding of the role of the judiciary, the manner in which the courts function and the history of the relationship between the courts and other organs of government. This is particularly important because…the independence and authority of the judiciary, upon which the maintenance of a just and free society so largely depends, in the end has no more secure protection than the strength of the judges themselves and the support and confidence of the public.”

There is persisting public interest in the work of the criminal courts in particular. While that is evident from periodic criticism for perceived leniency in sentencing, there is an underlying genuine wish to comprehend the working of the courts in that particular jurisdiction.

That was interestingly apparent in October last year, when ABC Radio hosted a mock trial in the Banco Court in Brisbane, a direct broadcast live on morning radio. The 612 morning presenter, Ms Madonna King, compered the event, with Judge Dick on the bench, the Director of Public Prosecutions, Mr Tony Moynihan SC as prosecutor, and Mr Rob East from Legal Aid Queensland as defence counsel. There were other participants: from Corrective Services, Legal Aid, the University of Southern Queensland and the media. That it occupied the whole of Ms King’s morning radio session illustrated the ABC’s assessment of that level of public interest, noting that 612 morning radio has a listener catchment comprising 120,000 persons. The “jury” comprised 140 members of the public, all of whom had applied in advance for a berth. It was kept at that number so the event would be manageable. I was told that the feedback to the ABC was substantial and positive. This was a good recent instance of worthwhile community engagement by our courts.

I have spoken of the public’s interest in the work of the courts in this State, and I have offered my thesis as to the reason for that confidence.

Unlike any other court within the Australian federation, the work of the Supreme Court of Queensland is accomplished in a large number of centres throughout the State. In that sense, the development of the Court has followed the development of the separated colony, then State.

The Supreme Court sits, as required, in 11 centres as well as Brisbane: Cairns, Townsville, Mt Isa, Mackay, Rockhampton, Longreach, Bundaberg, Maryborough, Toowoomba, Roma and Southport. There are resident Supreme Court Judges in Cairns, Townsville and Rockhampton.

Necessary decentralization, a feature of both executive government and the judicial branch in this State, extends also to the District and Magistrates Courts. More dramatically than with the Supreme Court, the District Court sits at 44 regional centres, and Magistrates Courts in 106. Consistently, of a State-wide profession exceeding 8,000 practitioners, almost one-fifth practise outside Brisbane. There are substantial local professions operating in six centres: Rockhampton, Mackay, Townsville, Cairns, the Gold Coast and Toowoomba, about 4,500 practitioners in total, more than 700 here at the Gold Coast.

Since the early days of the separated colony, there has been an acknowledgement that where practicable, courts should go to the people rather than the reverse. Two centuries ago, Supreme Court Judges embarked on greatly inconvenient journeys — on horseback and by coastal steamer — to service circuit centres. These days, Magistrates especially, endure considerable burdens servicing Cape and Torres Strait communities.

In relation to the basic objective, I was disappointed in 2002 when events conspired to prevent the trial of Mr Long, the Childers backpacker murderer, in Bundaberg, which is the closest Supreme Court centre to Childers. As I said in the course of delivering a pre-trial ruling ((2002) 1 Qd R 681, 682): “Recognizing the decentralized nature of the State, it is fundamentally important that a trial ordinarily proceed in the district of the alleged offence.” I am very pleased to acknowledge the executive’s support for court sittings in remote centres with, for example, Magistrates resourced to attend remote Torres Strait centres, lest defendants endure potentially life threatening dingy trips, without their having the fuel to survive (because they cannot afford to buy it).

The comparative remoteness of some court centres has obviously affected, in a number of respects, the way the Court proceeds. For an historical and now aging example, the Court used not to sit on Easter Tuesday, so that parties and witnesses in proceedings adjourned over the Easter period could make sometimes arduous journeys back to courthouses without losing their break.

We have for many years been conscious of the need to avoid imposing unnecessarily on witnesses, and in putting it that way, I am sure Sir James Cockle and Sir Samuel Griffith were similarly impelled. But in these distant lands, our experience intrigues those outside.

I recall the intrigue of some English judges when I informed them in the late 1980’s that our Supreme Court not infrequently took evidence by telephone.

When I was first appointed Chief Justice, I travelled to Longreach to conduct a murder trial. It was of some civic interest because I had lived in Longreach as a child, and also, it was to be the first time the Chief Justice had conducted court proceedings in that centre. Before I left Brisbane, a colleague suggested a conviction was unlikely (not that I was concerned) because Longreach juries never convict their own. The jaundice was surely misplaced. In fact this jury did convict — though I acknowledge the accused hailed from Barcaldine. That irrelevance aside, I mention the case now because of the telephone.

We took the evidence of a medical specialist centred in Rockhampton by telephone. The Longreach courtroom is most atmospheric: a colonial timber courthouse, with the courtroom itself distinguished by an old-style particularly attractively painted coat of arms hanging behind the bench. Contrary to expectations, when the bailiff telephoned the doctor, the call was taken, not by the doctor, but by his receptionist, who put us on hold while she fetched the doctor. The jury and I were then treated to a rollicking two minute rendition of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”. Unsurprisingly, on return to Brisbane, we put in place a protocol for the taking of evidence by telephone.

As we all know, technology has, in many forms over the decades, proved invaluable in the streamlining of court proceedings. I expect, before the end of my term, to see the advent of full electronic filing in Queensland courts, with appropriate accommodation of course for the situation of those without legal representation. Allowing for the nature of technological development, it would be foolhardy to seek to forecast other likely changes, but they are inevitable. Technological support greatly facilitates the dispatch of our work. Timeliness and other efficiencies would be lost, absent that support, with our contemporary case-load.

It amazes me to contemplate the prodigious workload reportedly undertaken by Sir Samuel Griffith while Chief Justice of Queensland from 1893 to 1903, bearing in mind the extremely primitive conditions — in our terms — in which he discharged it. There were only about five judges on the Supreme Court then, and the smallish colony obviously generated much less work for the Court.

It amazes me to contemplate the prodigious workload reportedly undertaken by Sir Samuel Griffith while Chief Justice of Queensland from 1893 to 1903, bearing in mind the extremely primitive conditions — in our terms — in which he discharged it. There were only about five judges on the Supreme Court then, and the smallish colony obviously generated much less work for the Court.

But nevertheless, as well as his court sittings commitments, Griffith took on numerous added burdens: especially, notably his single-handedly drafting the Criminal Code, which remains substantially intact to this day. There were no typewriters, let alone faxes, dictaphones, emails or computers. There was no air-conditioning. If true, as is said, that Griffith consumed half a bottle of Scotch whisky in his horse drawn carriage from New Farm to the courthouse in the morning, and the other half on the way home in the evening, then it is not explained by his origins — he was born in Wales. Perhaps Brisbane water was not then of its presently high purity. But if the whisky inspired his work ethic and stimulated his intellect, then we should be the grateful beneficiaries. It would certainly have eased the inconvenience of the primitive conditions in which he managed to accomplish so much.

Speaking incidentally of horse drawn carriages and the Supreme Court, may I be pardoned this personal observation? My great grandfather, Frederick de Jersey, maintained a hansom cab outside the Supreme Courthouse, and his passengers over the years included the Prince of Wales, Dame Nellie Melba, and regularly a succession of Chief Justices including Sir James Blair (1925 to 1940) and Hugh Macrossan (1940). Sir Charles Wanstall, who was Chief Justice of Queensland from 1977 to 1982, was born in the year 1912: the newborn Charles was taken home from hospital in the cab driven by my great grandfather. I had the privilege of being Sir Charles’ Associate in 1970. The “Courier Mail” archives retain a photograph of my great grandfather in his hansom cab outside the courthouse.

Coming back to the present, I observe that while the mission of the courts is immutable, and the fundamentals of our workings are not subject to change, the courts have of course nevertheless varied their approach consistently with reasonable current expectations.

A recent illustration is a response to the increased incidence of self-representation in the courts. Since the year 2007, a citizens’ advice bureau has operated from the Supreme and District Courthouse in Brisbane. It is modelled on a highly successful service which has operated from the Royal Courts of Justice in London now for many years. The initiative is called “accessCourts”, and includes a free-of-charge professional advice service run by the Queensland Public Interest Law Clearing House from the courthouse, in conjunction with a network of trained volunteers who assist persons involved in court proceedings through the process. Those volunteers are known as “blue jackets”. The service is operating most effectively, and with the financial support of the Queensland government. It is the first of its kind in Australia, and may be the first such service ever outside the United Kingdom. Its development was inspired, as I have said, by the increasing incidence of unrepresented litigants within our process. To illustrate the demand for the service, the last three months of last year saw 2,674 contacts between members of the public and network volunteers. Since 2007, the advice bureau has dealt with the problems of as many as 221 clients. As increasing the accessibility of justice remains a persisting challenge, this initiative goes some way in reducing the limits experienced by, frankly, too many members of our community.

I have sought today to distil the essence of the role of the Supreme Court in the life of this State.

If the public takes the Court for granted, then it pays the Court something of a compliment, in betraying implicit faith in the courts’ conscientious and effective discharge of its mission. But I believe there is an abiding active public interest in the work of all State courts, with the Supreme Court at the pinnacle, and it is an interest flavoured by confidence borne of the independence, transparency and predictability of the process. Ultimately, there is confidence in the healthy operation in this State of the rule of law.

May I say finally that the Supreme Court of Queensland, and thereby the people of our State, have also been the beneficiaries of the respect of our executive government, for the separation of powers and independence of the judiciary, and that has been conspicuous over recent decades. There is additionally an abiding acknowledgment by executive government of the significance of the role played by the Supreme Court in the good government of the people. Evidence of that acknowledgement rests in the courthouses themselves.

“The courthouse” has long symbolized the stability and security of the community it serves. A visit to regional centres confirms this. We see a fine courthouse, in the middle of town: a focal point for government and civil enforcement. And the government has properly recognized it should be an inspiring building. If you are fortunate to travel around Queensland, you will agree with my observation.

The Supreme Court sits in many fine courthouses throughout this State. Some were designed by the respected Colonial Architect F G D Stanley, including the grand Brisbane courthouse which was burned down in 1968, and the imposing existing courthouse in Maryborough. There is soon to be a new metropolitan courthouse.

Queensland will at last have a metropolitan courthouse optimally suited to the disposal of the mass of very serious work daily accomplished in the Supreme and District Courts. The 47 courtrooms and related facilities in the new complex will constitute essential infrastructure which will serve the people well for many years to come.

We tend to focus on utility, for the litigating public, jurors, court staff and prisoners. But that should not mask a broader, striking public vision.

As a former State Architect recently reminded me, this will be the most significant public building constructed in our capital city since the current Executive Building, which was completed some 37 years ago. 140 years after the opening of Parliament House in 1868, it is still breathtaking for Queensland citizens to gaze on that graceful seat of government.

143 years later in the year 2011, which will mark the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court, our citizens will, I am confident, be greatly impressed by a new emanation, at the other end of George Street, of their third branch of government.

143 years later in the year 2011, which will mark the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court, our citizens will, I am confident, be greatly impressed by a new emanation, at the other end of George Street, of their third branch of government.

What is emerging at the Roma Street end of George Street will fix public perceptions of the role of the Supreme Court upon the reality, which is its being a bastion of independence and objectivity in the delivery of justice according to law. The inspired design of the new building will reflect the challenge of that mission, and the building’s utility will help assure the fulfilment of the undertaking. I imagine the litigation bar especially will be interested to move in due course into what will become a district legal precinct, with all State and Commonwealth courts in close proximity.

And so, almost 150 years have passed, and the immutability of our mission will take the Court forward. In times of global turmoil and insecurity, people tend to find reassurance in values, beliefs and institutions of unchanging fundamentals: the Supreme Court of Queensland is one such institution, inspiring for the reliable discharge of its mission over many years past, and reassuring for the confidence that with the valued support of the profession, it will continue to do so indefinitely into the future.

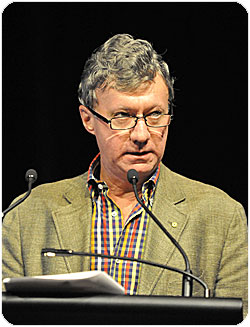

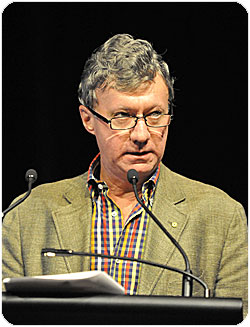

The Honourable Paul de Jersey AC

I am very pleased to add my welcome to Chief Justice French to this jurisdiction, on his first visit in his capacity as Chief Justice of Australia.

I am very pleased to add my welcome to Chief Justice French to this jurisdiction, on his first visit in his capacity as Chief Justice of Australia. And the Bar would have been diminished absent the cohesion engendered by our host, the Bar Association of Queensland, which annually succeeds in convening the best attended bar conference in the nation. The Association reaches its 106th anniversary this year. Its insignia helpfully remind us of the goals and traits which characterize both bar and court, while acknowledging the public orientation of both.

And the Bar would have been diminished absent the cohesion engendered by our host, the Bar Association of Queensland, which annually succeeds in convening the best attended bar conference in the nation. The Association reaches its 106th anniversary this year. Its insignia helpfully remind us of the goals and traits which characterize both bar and court, while acknowledging the public orientation of both.  Our historical perspective of the Supreme Court tends to lionize the legendary leadership of Sir Samuel Griffith. His monumental, even Olympian, contribution cannot, however, be allowed to obscure the fact that the first Chief Justice was Sir James Cockle, credited with restoring harmony to the relationship between the Supreme Court and the government, by quelling a turbulent Lutwyche. Cockle was a person, you may recall, who was also able to discover lyrical aspects in algebraic equations. I commend Dr John Bennett’s biography in the “Lives of the Australian Chief Justices” series.

Our historical perspective of the Supreme Court tends to lionize the legendary leadership of Sir Samuel Griffith. His monumental, even Olympian, contribution cannot, however, be allowed to obscure the fact that the first Chief Justice was Sir James Cockle, credited with restoring harmony to the relationship between the Supreme Court and the government, by quelling a turbulent Lutwyche. Cockle was a person, you may recall, who was also able to discover lyrical aspects in algebraic equations. I commend Dr John Bennett’s biography in the “Lives of the Australian Chief Justices” series. It amazes me to contemplate the prodigious workload reportedly undertaken by Sir Samuel Griffith while Chief Justice of Queensland from 1893 to 1903, bearing in mind the extremely primitive conditions — in our terms — in which he discharged it. There were only about five judges on the Supreme Court then, and the smallish colony obviously generated much less work for the Court.

It amazes me to contemplate the prodigious workload reportedly undertaken by Sir Samuel Griffith while Chief Justice of Queensland from 1893 to 1903, bearing in mind the extremely primitive conditions — in our terms — in which he discharged it. There were only about five judges on the Supreme Court then, and the smallish colony obviously generated much less work for the Court. 143 years later in the year 2011, which will mark the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court, our citizens will, I am confident, be greatly impressed by a new emanation, at the other end of George Street, of their third branch of government.

143 years later in the year 2011, which will mark the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court, our citizens will, I am confident, be greatly impressed by a new emanation, at the other end of George Street, of their third branch of government.