FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 75 Articles, Issue 75: June 2016

Corporations Act

Paper delivered to Queensland Bar Association CPD Program 14 April 2016

A liquidator’s primary task in carrying out the winding up of a company is simple: get in all the assets available to the company’s creditors and pay them out to the persons entitled to those assets according to law.

Where the winding up involves an insolvent company, the underlying premise of the winding up is to ensure that unsecured creditors share rateably in the assets available to meet their unpaid debts and claims: the pari passu principle. For all the in-roads, modifications and exceptions made by statute, it remains the guiding principle upon which insolvent administration is based.

Of course, the pari passu principle can be applied to the assets of the company on hand at the time of the winding up. However, creditors have an incentive to grab as much as they can before the fateful day, and the company and its controllers have an interest in paying out as much of the company’s assets as possible to particular creditors (such as those holding personal guarantees) or to their own benefit, before the company is wound up, to the detriment of the general body of creditors.

For centuries, the law has sought to give effect to a broader notion of the pari passu principle by ensuring that some creditors (or other persons) are not unfairly benefited over the general body of creditors by the insolvent company by dealings prior to the winding up.

Provisions which permitted the recovery in bankruptcy proceedings of what would now be called unfair preferences have been on the statute books since 1570. Provisions which permitted the recovery in bankruptcy proceedings of what would now be called uncommercial transactions have been in place since 1604.

The statutory regime with which we are concerned today is contained in Part 5.7B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) entitled “Recovering property or compensation for the benefit of creditors of insolvent company”. That statutory regime was first introduced into Australian company law in 1993.

Prior to that time, the scheme which regulated liquidators’ recovery actions was that provided for by s. 565 Corporations Law (and its legislative forebears). Section 565(1) Corporations Law provided:

A settlement, a conveyance or transfer of property, a charge on property, a payment made, or an obligation incurred, by a company that, if it had been made or incurred by a natural person, would, in the event of his or her becoming a bankrupt, be void against the trustee in the bankruptcy, is, in the event of the company being would up, void against the liquidator.

The effect of this provision was to incorporate the avoidance provisions of the Bankruptcy Act into the corporations context. This created ambiguities in the operation of the avoidance provisions in the corporate context.

These ambiguities led the Harmer Commission to recommend the introduction of specific avoidance provisions in the then Corporations Law. The avoidance regime which now exists in Part 5.7B Corporations Act was thereafter introduced in the Corporate Law Reform Act 1992 (Cth).

This explains why there are no cases on the provisions in Part 5.7B before 1993 and why cases from that earlier period in the corporate context are frequently concerned with provisions from the Bankruptcy Act.

Overview of the Statutory Regime for Voidable Transactions

The statutory regime introduced in 1993 is rather complex. Careful attention has to be paid to the particular structure of the Part and to the particular elements of each cause of action.

There are eight Divisions in Part 5.7B.

Brent and I will be concerned today with Division 1, entitled “Preliminary”, and Division 2, entitled “voidable transactions”.

There are, however, a number of other important provisions in Divisions 2A to 7. These relate to matters which include:

(a) The circumstances in which PPSA security interests will vest in a company (Division 2A); and

(b) Insolvent trading (Divisions 3 to 6).

Scheme of Division 2: Voidable transactions

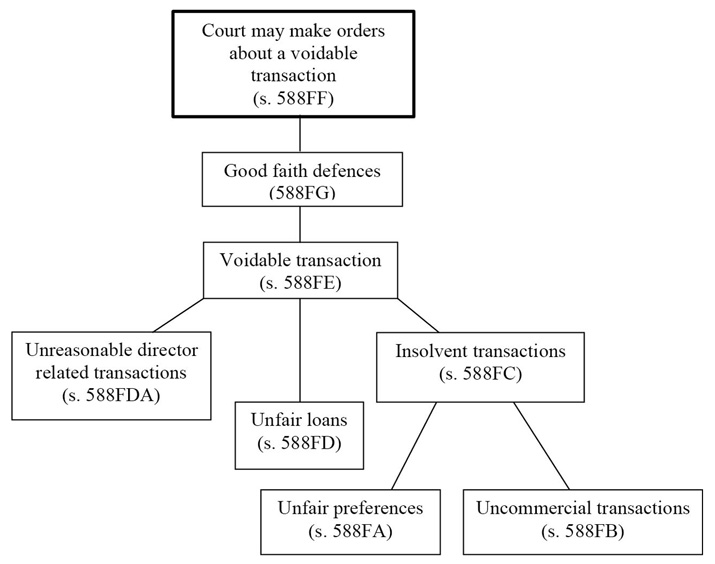

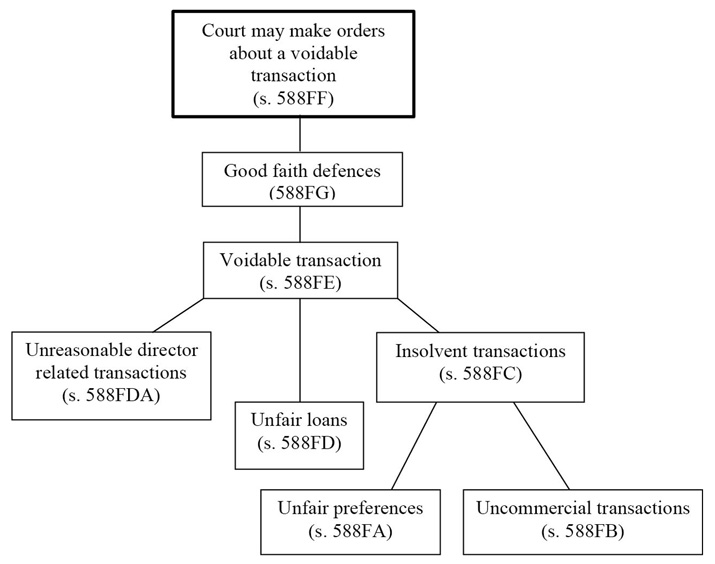

For those who are unfamiliar with Division 2, it might come as a surprise to know that the causes of action conferred on liquidators by the Division are not to recover a

preference or to set aside an uncommercial transaction. Rather, the Division adopts the somewhat unwieldy approach shown in the diagram below:

There are a number of matters to note by way of overview.

Single cause of action under s. 588FF

The cause of action conferred by Division 2 is not one to set aside a preference or an uncommercial transaction. Strictly speaking, the cause of action is that created by s. 588FF. That section confers power on the Court, on the application of the liquidator, to make one or more of a wide range of orders if satisfied that a transaction is voidable under s. 588FE. Accordingly, the task of the liquidator is to make out all the elements of a voidable transaction under s. 588FE.

Four basic transactions

There are four basic kinds of transaction that can comprise a voidable transaction (specific transactions):

(a) An unreasonable director related transaction;

(b) An unfair loan;

(c) An unfair preference which is also an insolvent transaction; and

(d) An uncommercial transaction which is also an insolvent transaction.

The specific transactions route to voidable transaction status is as follows:

(a) For each of the specific transactions, the elements are identified in the specific statutory provisions identified in the flow chart;

(b) The additional requirement to make an unfair preference or an uncommercial transaction into an insolvent transaction is made out where the company is insolvent at the time of the transaction or becomes insolvent because of the transaction; and

(c) The additional requirement that makes one of the four specific transactions into a voidable transaction is that the transaction in question occurred after certain dates determined by reference to the “relation-back day”.

Timing issues under s. 588FE

The relation-back day is usually the date of the filing of the winding-up order or, if the winding up was preceded by some other insolvency administration (such as voluntary administration), the date of the commencement of that administration. Be aware, therefore, that in some circumstances, the identification of the correct relation-back day might require some careful consideration of the journey of the particular company to insolvency. The definition of “relation-back day”[1] refers one to Division 1A of Part 5.6, which contains the detailed provisions applicable.

The period in which a transaction may be impeached as a voidable transaction differs for each of the specific transactions:

(a) For an unfair preference, the transaction will be a voidable transaction if the transaction or an act done to give effect to it occurred within 6 months prior to the relation-back day;[2]

(b) For an uncommercial transaction, the voidable period is 2 years prior to the relation-back day;[3]

(c) An unfair loan is a voidable transaction whenever it was entered into; and

(d) An unreasonable director related transaction will be voidable if it is entered into 4 years prior to the relation-back day.

Sections 588FE(4) and (5): Extended periods for insolvent transactions

Section 588FE also introduces two additional distinct voidable insolvent transactions by way of identification of extended voidable transaction periods:

(a) Section 588FE(4) provides that an insolvent transaction is a voidable transaction if a related entity of the company was a party to the transaction and it was entered into within 4 years prior to the relation-back day; and

(b) Section 588FE(5) provides that an insolvent transaction is a voidable transaction if the company became a party to it “for the purpose, or for purposes including the purpose, of defeating, delaying, or interfering with, the rights of any or all of its creditors on a winding up of the company” and it was entered into within 10 years prior to the relation-back day.

There are a couple of points to note about these provisions.

First, the use of the expression “insolvent transaction” in each of those provisions means that not only will an uncommercial transaction be caught by those provisions, but so will an unfair preference. That is, despite 6 months being the commonly understood period applicable to transactions said to be unfair preferences, this period can be extended to 4 years if a party to the preference was a related entity, and 10 years if the purpose of the unfair preference was interference with the rights of creditors on a winding up. The provisions do not seem to be applied often[4] but it is something to be kept in mind.

Second, s. 588FE(5) is the method by which the concept of a transaction to defeat creditors is introduced into Division 2. Equivalent provisions exist in s. 228 Property Law Act 1974 (Qld) and cognate statutory provisions in other states, and in s. 121 Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth). Section 228 applies where there is an “alienation of property…with intent to defraud creditors”. Section 121 uses the concept of purpose and is in generally analogous terms to s. 588FE(5).[5]

There are numerous authorities dealing with these provisions and their scope and application, particularly the character of the state of mind required.[6] While similar issues arise in all three, and cases on the other provisions can assist in the interpretation and application of the Corporations Act provision, careful attention must be paid to the particular form of the statutory provision.

One particular difference between s. 588FE(5) and those other provisions is that s. 588FE(5) requires the liquidator to prove that the company was insolvent at the time the transaction was carried out. It is not enough to prove that it was carried out with the purpose of defeating or delaying creditors. It is difficult to see why this additional requirement is appropriate if the purpose to defeat or delay creditors is established. It adds to the difficulty of establishing this kind of voidable transaction. It might explain why s. 588FE(5) does not appear as decisive in many decided cases.

The problem was addressed to some extent by the introduction of s. 588FDA which makes unreasonable director related transactions voidable transactions without the requirement of proving insolvency.

Section 588FF: Orders about voidable transactions

Section 588FF(1) provides that on the application of the liquidator, the Court may make one or more of a range of orders where the Court is satisfied that a transaction is voidable under s. 588FE.

Section 588FF also identifies the limitation periods applicable to the causes of action conferred by that section. An application under s. 588FF(1) must be brought within 3 years after the relation-back day or 1 year after the appointment of the liquidator, whichever is the later.[7]

However, the Corporations Act also recognises that these periods can be insufficient. Section 588FF(3)(b) provides that the limitation period can be extended on application by the liquidator made prior to the expiry of the default limitation period. This requirement must be strictly complied with. It has been authoritatively determined that it covers the field and there is no scope for extensions to be granted under general provisions like s. 1322(4)(d) Corporations Act.[8]

Applications under this provision must be prepared with care, particularly if a “shelf” order is sought extending time generally, rather than with respect of specific claims. Particular care has to be taken in seeking such a shelf order if there are particular claims of which the liquidator is or should be aware at the time of the application. In that case, notice of the application might have to be given to the relevant potential respondent and orders sought specifically in respect of such potential claims.[9]

588FG: Defences

Although referred to as a defence provision, s. 588FG does not use that term. Rather it imposes limitations on the orders which a court can make under s. 588FF. It provides that a court is not to make an order under s. 588FF which materially prejudices the interests of two classes of persons.

(a) The first class is persons who were not parties to the voidable transaction which the liquidator has established. Section 588FG(1) applies to that class of person. It applies where the third party received no benefit or, if they did, the benefit was received in good faith and without reasonable grounds for suspecting insolvency. A non-party does not have to show that they provided consideration for any benefit received.

(b) The second class is persons who were parties to the voidable transaction. Section 588FG(2) applies to that class of person. It applies where the person:

(i) Became a party to the transaction in good faith without reasonable grounds for suspecting insolvency; and

(ii) Provided consideration or changed position in reliance on the transaction.

Despite the provision not being cast expressly in the form of a defence, it has been held that the onus of establishing that a person has the benefit of one of the exculpatory provisions lies on the respondent.[10]

Read more… Download full article

Footnotes

- Section 9 Corporations Act.

- Note s. 588FE(2) applies not to an unfair preference but to an insolvent transaction. This will also include an uncommercial transaction which is an insolvent transaction, though there follow specific provisions which deal with various kinds of uncommercial transaction.

- Section 588FE(3).

- For some examples where the provisions were discussed see International Cat Manufacturing Pty Ltd & Anor v Rodrick & Ors [2010] QSC 30 at [12] and [13]; Warner v Wong, in the matter of Bellpac Pty Limited (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (In Liq) (No 5) [2015] FCA 784 at [282] to [299].

- See s. 121(1)(b) Bankruptcy Act: this section includes further provisions to assist in demonstrating the purpose identified which are not present in s. 588FE(5).

- Leading authorities of recent times include: PT Garuda Indonesia v Grellman (1992) 107 ALR 199; Cannane v J Cannane Pty Ltd (1998) 192 CLR 557; Trustees of Cummins v Cummins (2006) 227 CLR 278 esp. at [36] to [41]; Jedhar Pty Ltd v Grosse [2004] QCA 167; The Beach Retreat P/L & Anor v Mooloolaba Marina Ltd & Anor [2008] QCA 224; Chen v Marcolongo (2009) 260 ALR 353; Marcolongo v Chen (2011) 242 CLR 546.

- Section 588FF(3)(a).

- BP Australia Ltd v Brown (2003) 58 NSWLR 322 at [114]-[129] per Spigelman CJ with whom Mason P and Handley JA agreed; approved in Gordon v Tolcher (2006) 231 CLR 334 and [37]-[40]; Grant Samuel Corporate Finance Pty Ltd v Fletcher (2015) 317 ALR 301 at [23]-[25].

- Fletcher (as Liquidators of Octaviar Administration Pty Ltd) v Anderson (2014) 103 ACSR 236 a decision of the NSWCA.

- Cook’s Construction Pty Ltd v Brown (2004) 49 ACSR 62 at [1] per Young CJ (in Eq) with whom Hodgson and Santow JJA agreed.