The Man

The Man

Julian Burnside QC is a polymath. He reminds this reviewer of the nineteenth century amateur learned man, popping up unexpectedly in one area of learning or another, reading a paper on mathematics at the Royal Society; publishing an illustrated book on Plants of the Congo; and reforming the Royal Mint.

Mr. Burnside’s accomplishments include a children’s book, Matilda and the Dragon; a book on the uses and abuses of the English language, Wordwatching: Fieldnotes of an Amateur Philologist; and, as editor, From Nothing to Zero: letters from refugees in Australia’s detention centres. His website2 which doubles as a site for Liberty Victoria, the Victorian equivalent of Queensland Council for Civil Liberties, is a simple but extraordinarily useful database of links to information on a broad range of topics but with a particular focus on the plight of asylum seekers and human rights information, generally.

Mr. Burnside is a busy commercial silk whose portfolio of involvement in important human rights cases in Australia is second to none. On top of all that, he seems to be flying to all corners of Australia on at least a weekly basis delivering a powerful defence of justice, both procedural and substantive, and the rule of law and an equally powerful critique of those who display little love for those concepts.

And in all of that, Mr. Burnside achieves a writing and speaking style that matches complex subjects with simplicity of language and easy accessibility. He is a master of the art that conceals art.

The Book: The Methodology

The Book: The Methodology

Even knowing all of that, Watching Brief still astounds with the range of subject matter covered and the brilliant narrative which emerges from that range. Watching Brief incites the compulsion of the thriller in a text which covers autobiography and recent political and legal history against a background of the more distant human rights struggles on which the foundation stones of modern democratic practice and theory are based. And that’s not all.

Mr. Burnside displays one of the key attributes of storyteller and teacher, the ability to find themes across different subject matter and to use those themes to draw comparisons. Thus lessons are drawn, and the familiarity of well worn narratives are used, to enhance and emphasise political points made concerning current and recent events.

Mr. Burnside also knows well the architecture of the human heart, our strange ability to fail to blanch at stories of millions being tortured and killed while chaining ourselves to the television to follow the story of a single stranded whale or a boy trapped down a well. So, the small heroes of his speeches and essays have names and personal histories. The parties in his case reports have personalities that spill out across the page. And many of his subjects tell their stories in their own powerful words even when their English fails to be perfectly framed.

The Book: The Content

Watching Brief is primarily comprised of speeches and essays prepared by the author since 2001. They are edited to avoid repetition and cross-referenced to allow easy access to information appearing elsewhere in the book on a similar or related subject. As the Preface warns, the chapters, especially, those on Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers, because of the time that they were written, describe circumstances that have since changed.

Early Days

Part 1, entitled Foundations, is by far the shortest of the four Parts of Watching Brief. It recounts a little of the author’s social and intellectual origins and may surprise many who are aware of Mr. Burnside’s powerful advocacy on human rights and justice issues. Among anecdotes of particular teachers, Chapter 1 reveals that Mr. Burnside is an alumnus of Melbourne Grammar School; that he was, until his senior years, an indifferent student; and that his sense of personal inadequacy had impacted upon his ability to relate easily to friends.

The second chapter discusses the author’s introduction and early development at the Bar. His practice developed slowly and led into the company and taxation fields. The takeover boom in the early eighties led to his practice becoming busier and to his getting to work with the top counsel of the time. The second half of the 90s saw involvement in a different run of cases including acting for the Maritime Union against Patrick Stevedores and Mr. Burnside’s advocacy in support of the rule of law and against injustice was sparked by these experiences.

Julian Burnside’s emergence as a social commentator concerned about injustices in our society contrasts with a number of commentators who have become ideologues of the right. Many such commentators have started as ideologues of the left and have drifted across the political spectrum and taken up their present raucous positions.3 Mr. Burnside, on the other hand, has come from a conservative background (he voted Liberal in every election up until 1996) without significant political involvement so that, when his awakening occurred, it has been much more issue and rule of law based and free of broader ideological overtones apart from his ever present concern with justice and the rule of law.

Burnside’s New Core Business: Asylum-seekers in Australia

It is not surprising, considering the author’s work in the area, both as an advocate in Courts and Tribunals and as a public advocate, that nine chapters and more than 100 pages would be devoted to the plight of asylum-seekers in Australia.

Mr. Burnside develops social criticism of government action and inaction in these chapters. He develops his critique against a well-articulated framework of values and ideas and legal concepts, including concepts taken from international and domestic law including that of “crimes against humanity”. The advocacy always retains its immediacy and its impact. One reason for this is the author’s use of actual events happening to real people.

Mr. Burnside develops social criticism of government action and inaction in these chapters. He develops his critique against a well-articulated framework of values and ideas and legal concepts, including concepts taken from international and domestic law including that of “crimes against humanity”. The advocacy always retains its immediacy and its impact. One reason for this is the author’s use of actual events happening to real people.

In the introductory chapter to Part 2, in order to make the point that asylum seekers are not “people who come to Australia to improve their economic circumstances who are placed by the government in holiday camps”, the situation of a family of Iranian Christians placed in Woomera is discussed. A description of a ten year old girl of the family who had stopped eating and begun scratching herself constantly, by a Child Mental Health Agency, is set out as follows:

“[She] does not eat her breakfast or other meals and throws her food in the bin. She was preoccupied constantly with death, saying, ‘don’t bury me here in the camp, bury me back in Iran with grandfather and grandmother’.

[She] carried a cloth doll, the face of which she had coloured in blue pencil. When asked in the interview if she would like to draw a picture, she drew a picture of a bird in a cage with tears falling and a padlock on the door. She said she was the bird …”

In dismantling the government’s misinformation campaign directed to denigrate asylum-seekers as “illegals” and present a sanitised version of its treatment of asylum-seekers, one essay makes use of Howard government rhetoric of “a fair go” and contrasts the rhetoric with the actual circumstances of asylum-seekers. Again, the author makes powerful use of the particular, this time, drawing on letters from individual people including the following extract:

“I am a 30-year-old Iranian man. I came to Australia to seek refuge. I had a very difficult trip and in few occasions I saw my own death! …

I have been in this cage for 13 months … Why should all these women and children … be in this cage? What have we done? Where should we seek justice? Who should we talk to and tell our story? Aren’t we human beings? … I don’t know what my crime is. …”

The final chapter in Part 2 is dated April 2007. The author notes the release of the last two refugees caught up in the Pacific solution, who had been imprisoned for five years, first on Manus Island and then Nauru. Mohammed Faisal was granted permanent protection and Mohammed Sagar travelled to Sweden. The combination of some Labor backbone and a stand by Liberal backbencher, Petro Georgiou, and a few of his colleagues forced the Howard government to back down on a plan to expand the Pacific solution to imprison 43 West Papuan asylum-seekers. The tide appeared to have turned, as the author notes.

However, he also notes that mandatory detention remains a reality and a $400 million high tech detention centre nears completion on Christmas Island with solitary confinement cells and special isolation facilities for children and infants.

Kevin Andrews’s gratuitous denigration of the African-Australian community in Australia in the second half of 2007 shows that the temptation for Australian governments to use defenceless people for political gain has not receded. The lessons of the last seven years and more, so persuasively documented in Part 2 of Watching Brief, have not lost any of their relevance.

Terrifying Law 4

Part 3 of Watching Brief is entitled Human Rights in an Age of Terror. The speeches and essays contained therein analyse and criticise Australia’s legislative and policy responses to terrorism, especially, in the wake of the attacks on New York and Washington of 11 September 2007.

The author places this part of Australia’s recent history in its historical context, a method which adds great impact to the criticisms made. The analysis commences with the Gunpowder plot of 5 November 1605, an analogous but failed act of political violence inspired by extreme religious views.5 The essay recounts the immediate response to the plot by torturing Guido Fawkes (the “Guy” of Cracker Night legend) by use of the rack leading to the identification of other suspects and the prosecution and execution (by hanging, drawing and quartering) of others who were innocent of the plot but happened to share the same religion as the conspirators.

The longer term aftermath, however, of the events of 1605 was the battle to establish the rule of law in England including the Petition of Right in 1627; the Civil War of 1642-9; the passing of the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679; the Glorious Revolution of 1688; and the final establishment of a monarchy subject to the rule of law with the Act of Settlement of 1701.6

In contrast, the longer term aftermath of the events of 11 September 2001 seems a departure from the rule of law in countries including Australia and the United States and an increasing lack of commitment to its tenets by those who exercise power and influence.

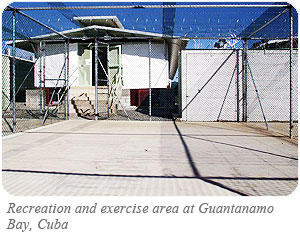

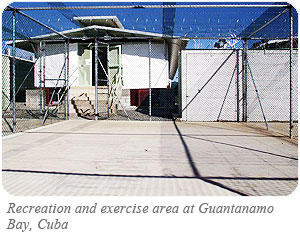

As with his other writing, it is particularity which gives force to the arguments used. The essay contrasts another historical event, the adoption of the US Constitution and its Bill of Rights reflecting the values of the Petition of Rights, 150 years earlier, to the current administration’s abandonment of the Geneva Convention in its treatment of captured combatants. He contrasts the requirements of the Geneva Convention (and the alternative regime for the treatment of criminal suspects): humane treatment; no interrogation beyond name, rank, and serial number; and release at the end of hostilities to the notorious memo of Alberto Gonzales.7 Gonzales advised President Bush of the advantages of declaring prisoners at Guantanamo to be not amenable to the provisions of the Geneva Convention. The advantage, it was said, was flexibility. It would allow US officials who breached the terms of the Geneva Convention to avoid amenability to prosecution for War Crimes.

Gonzales’ memo was followed, six months later, by the “torture memo” of Jay Bybee, then serving as Assistant Attorney-General for the Office of Legal Counsel.8 This memo, after identifying seven techniques recognised as torture such as severe beatings, burning with cigarettes, electric shocks to genitalia, and rape or sexual assault, blithely advises:

“While we say with certainty that acts falling short of these would not constitute torture … we believe that interrogation techniques would have to be similar to those in their extreme nature and the type of harm caused to amount to torture …”

The essay then sets out accounts of treatment at Guantanamo taken from the affidavits of the Tipton Three, the three English nationals who were released at the insistence of the British government; who had gone to Afghanistan to provide humanitarian aid; and who have not been charged with any offence either before or after their release. While the space does not allow the inclusion of these descriptions in this review, they amply show the slippery slide that commences when lawyers encourage bureaucrats and politicians to defy the norms laid down in international law to ensure that captives are treated decently. They also amply justify the author’s observation that “It is impossible to reconcile these events with the values which are basic to our democratic system”.

The essay then sets out accounts of treatment at Guantanamo taken from the affidavits of the Tipton Three, the three English nationals who were released at the insistence of the British government; who had gone to Afghanistan to provide humanitarian aid; and who have not been charged with any offence either before or after their release. While the space does not allow the inclusion of these descriptions in this review, they amply show the slippery slide that commences when lawyers encourage bureaucrats and politicians to defy the norms laid down in international law to ensure that captives are treated decently. They also amply justify the author’s observation that “It is impossible to reconcile these events with the values which are basic to our democratic system”.

Part 3 also directs its attention to the legislation passed in Australia since 11 September 2001. This includes 2002 amendments to the ASIO legislation permitting incommunicado detention, for a week at a time of people not suspected of any wrong doing; and the 2005 amendments to the Criminal Code which permit the Australian Federal Police to apply for an order jailing a person for up to 14 days in circumstances where the person has not been charged with any offence and where persons are not permitted to know the evidence on which the order, obtained in their absence, was obtained. And this against a background where secrecy provisions carrying heavy penalties prevent publication of the fact that the person is being held for questioning.

Mr. Burnside reserves his harshest criticism for the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act (“the NSI Act”). The Act obliges any person in any kind of proceeding who might, by asking a question, tendering a document or in any other way, adduce evidence relating to an expansively defined “national security” to notify other parties in the hearing and, ultimately, the Attorney-General of the relevant evidence. The Attorney-General may then certify, conclusively, that adducing the evidence would prejudice national security, leading to a secret and heavily weighted court hearing from which the party seeking to adduce the evidence may be excluded. And if the Court (which is directed to give the greatest weight to the certificate of the Attorney-General) so decides, in this secret hearing, the party is prevented from adducing the evidence, no matter how crucial it might be to the party’s case whether it be the defence of a serious criminal charge or an action for damages to establish the lawfulness of treatment by a government agency or any other civil or criminal proceeding.

Space prevents discussion of many other aspects of the actions of Australian legislatures, politicians and officials over the last several years.

Part 3 of Watching Brief serves an excellent purpose for those of us who have watched with concern as one draconian law after another was passed and perhaps spoken up at the time and perhaps not. Watching Brief reminds us of the cumulative effects of the large number of such laws and gives us a chance to shock ourselves free of the desensitising effect of the sheer number and repetitive nature of the public relations spin to which we have been exposed. Watching Brief is a timely reminder and a call to arms to ensure that these laws do not remain on the statute books, indefinitely, simply because those of us who care about the rule of law have come to accept a new status quo as legitimate.

Collected Highlights of the Law

Part 4 of Watching Brief is entitled Justice and Injustice. It contains a disparate but intensely fascinating collection of essays on famous legal cases from recent and more distant times. Each essay (and the case it discusses) provides an historical moral lesson. In some cases, such lessons go to the heart of injustice and involve similar themes to Parts 2 and 3 of Watching Brief with their respective concentration on Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers and Australia and other countries’ responses to post September 2001 terrorist threats. Other such lessons are more personal and homely and reflect on the tragic and heroic aspects of human nature which find their expression in times of great stress.

This reviewer was familiar with some of the cases discussed and with some he was not. In either circumstance, the book’s treatment of the events is spell-binding. No essay failed to provide a new perspective or an enlightening reflection.

The cases discussed include the execution of Van Nguyen in Singapore for a drug related offence on 2 December 2005. This essay uses the famous address of Clarence Darrow in the case of Leopold and Loeb in Chicago in 1924 to argue the need for a consistent stand against capital punishment, a lesson still to be learned by John Howard and Kevin Rudd, as they displayed during the faux election campaign of 2007. Other cases include the prosecution of Roger Casement for treason and the questionable role played therein by famous English advocate, FE Smith (later Lord Birkenhead); the Oscar Slater case (a great example of the dangers posed by an overzealous police force and the importance in criminal investigation of keeping an open mind); and the Adolph Beck case (one of the best examples of the dangers of relying without more on identification evidence). The sheer bizarre or the interest of human drama arise from the discussion of Dr. Crippen’s almost perfect crime in murdering his wife; the case of Alma Rattenbury and her much older husband and much younger lover; and the successful self-defence by Noel Pemberton-Billing on a charge of criminal libel in the “Black Book” case.

In each essay, the author manages to convey the events as human drama and allows the reader to appreciate the central characters as human actors, no matter how unusual or dramatic are the events in which they play their part.

A Parting Word

The reviewer makes no apology for sharing many of the values and agreeing with much of the critique expressed in Watching Brief. The book is a very valuable collection of the important analysis and discussion for which Julian Burnside QC has been responsible over a period approaching a decade. I am a great admirer of the achievements of Julian as he has campaigned tirelessly during that period often with little support from politicians and news media who should have known and done better.

The book is more than that however. It is a fascinating read. Mr. Burnside is a great communicator and his analysis and argument is not only clearly and simply presented but also accompanied by narrative that is full of interest.

My recommendation is that you pursue one of the following three alternatives. Persuade someone close to you to buy Watching Brief for you. Alternatively, buy it for someone who lives in the same house as you so you can steal it and read it first. If all else fails, buy it for yourself. At recommended retail price of $32.95, you could do worse.

Stephen Keim SC

Footnotes

- Scribe is an independent Australian book-publishing company, founded by Henry Rosenbloom, in 1976. Its web address is http://www.scribepublications.com.au/.

- http://www.julianburnside.com.au

- Guy Pearse in High and Dry, Penguin Viking, 2007, notes a few of these at page 249. Christopher Pearson worked as an editor of Labor Forum. Andrew Bolt worked as a staffer for various Labor MPs. My favourite drift to the right was PP McGuiness who, when I first read him, worked on the staff of a young Bill Hayden.

- I am indebted to John Clarke and Brian Dawe for making this obvious connection.

- Another piece of historical context discussed in another essay in part 3 is the Dreyfus Affair, the scandalous series of events between 1894 and 1906 in which an exemplary Captain in the French Army’s general staff was framed and then tried on secret evidence of leaking information to Germany. Dreyfus’s status as a Jew and the strong anti-semitic feeling within the French military and political establishment appear to be the principal reasons why Dreyfus was not only convicted in the first instance on shaky evidence but prevented from clearing his name when the wrongfulness of the conviction had become evident to those in the higher echelons of the military. The lessons about the care required to ensure that persons are not unjustly treated because they belong to unpopular sections of society are very cogent for every Australian of Islamic background and have been highlighted by events touching this reviewer which were occurring as Watching Brief was going to print.

- An irony which the author does not point out is that, despite the progress made towards the rule of law, religious differences still affected rights at law and Catholics in England remained disadvantaged in 1701 as they had been in the lead up to the Gunpowder Plot.

- Gonzales was, later, Attorney-General from February 2005 until his forced resignation amid a series of scandals including allegations of perjury to Congress on 17 September 2007.

- Jay Bybee was, subsequently, appointed a Federal Court judge. He was nominated by President Bush on 22 May 2002 and confirmed by the Senate on March 13, 2003.

The Man

The Man The Book: The Methodology

The Book: The Methodology Mr. Burnside develops social criticism of government action and inaction in these chapters. He develops his critique against a well-articulated framework of values and ideas and legal concepts, including concepts taken from international and domestic law including that of “crimes against humanity”. The advocacy always retains its immediacy and its impact. One reason for this is the author’s use of actual events happening to real people.

Mr. Burnside develops social criticism of government action and inaction in these chapters. He develops his critique against a well-articulated framework of values and ideas and legal concepts, including concepts taken from international and domestic law including that of “crimes against humanity”. The advocacy always retains its immediacy and its impact. One reason for this is the author’s use of actual events happening to real people.  The essay then sets out accounts of treatment at Guantanamo taken from the affidavits of the Tipton Three, the three English nationals who were released at the insistence of the British government; who had gone to Afghanistan to provide humanitarian aid; and who have not been charged with any offence either before or after their release. While the space does not allow the inclusion of these descriptions in this review, they amply show the slippery slide that commences when lawyers encourage bureaucrats and politicians to defy the norms laid down in international law to ensure that captives are treated decently. They also amply justify the author’s observation that “It is impossible to reconcile these events with the values which are basic to our democratic system”.

The essay then sets out accounts of treatment at Guantanamo taken from the affidavits of the Tipton Three, the three English nationals who were released at the insistence of the British government; who had gone to Afghanistan to provide humanitarian aid; and who have not been charged with any offence either before or after their release. While the space does not allow the inclusion of these descriptions in this review, they amply show the slippery slide that commences when lawyers encourage bureaucrats and politicians to defy the norms laid down in international law to ensure that captives are treated decently. They also amply justify the author’s observation that “It is impossible to reconcile these events with the values which are basic to our democratic system”.