FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 81 Articles, Issue 81: Dec 2017

Lord Atkin was born in Tank Street, Brisbane 150 years ago. A new exhibition at the Supreme Court Library explores the influences which made him a great jurist. One major influence was his remarkable father, who died aged 30, after a short career as a champion of liberal democracy in his adopted country. In 1937 Lord Atkin paid for a monument to his father at Sandgate to be restored. Over the last 80 years it has again fallen into disrepair. In this article, Justice Peter Applegarth introduces readers to the exhibition, and encourages support for a project that aims to restore the Atkin Monument.

One hundred and fifty years ago, Tank Street, Brisbane was, as the name suggests, the site of a large water tank. On 28 November 1867 James Richard Atkin was born in a cottage in Tank Street. His mother, Mary, was Welsh. His father, Robert, was Irish. Just before Christmas 1867, Robert Atkin wrote to his parents-in-law in Wales about celebrating Christmas in the heat of Queensland and about their grandson. He wrote:

“I am never tired of admiring your grandson who is, if the womenfolk are to be believed, an infant combination of Hercules and Apollo.”

Dr Kevin O’Doherty had attended the birth of Dick Atkin. In 1848, O’Doherty’s medical studies in Dublin had been interrupted when he was charged over disloyal things he had published. He received a ten year sentence and was transported to Tasmania. Eventually he came to Queensland as a highly regarded doctor. Robert Atkin’s 1867 Christmas letter reported:

“Mary had a very delightful Dr. He was exiled for the part he took in Smith O’Brien’s rebellion, and although opposed to him in politics, we are very good friends”.

Robert Atkin and Kevin O’Doherty may have had their differences over Irish independence, but as public figures and unpaid Members of Parliament, these friends had a shared vision about Queensland’s future. They and other reformers, like Charles Lilley, opposed the vested interests of the squattocracy. Robert Atkin argued for fairness towards people in the North, for new railways, and for new industries of cotton and sugar. Atkin described the Polynesian Labourers Act as a legalised system of kidnapping. He and his colleagues did not want Queensland to become a plantation state, built on slavery, like the Deep South of the United States had been.

Robert Atkin and Kevin O’Doherty may have had their differences over Irish independence, but as public figures and unpaid Members of Parliament, these friends had a shared vision about Queensland’s future. They and other reformers, like Charles Lilley, opposed the vested interests of the squattocracy. Robert Atkin argued for fairness towards people in the North, for new railways, and for new industries of cotton and sugar. Atkin described the Polynesian Labourers Act as a legalised system of kidnapping. He and his colleagues did not want Queensland to become a plantation state, built on slavery, like the Deep South of the United States had been.

Robert Atkin’s career as a campaigning journalist, newspaper editor and MP was short.

By late 1871 his health was in terminal decline, and his sons had travelled to Wales. He wrote beautiful letters to his son Dick, including one on his fourth birthday which instructed Dick to be always good and kind, and advised:

“If you are always truthful and honourable you will find the advantage of it as you grow older”.

Robert Atkin died at Sandgate in May 1872, aged only 30. Citizens from all sides of politics mourned his passing. One of them was a young lawyer named Samuel Griffith. Atkin only resigned from Parliament in March 1872 after he was assured that Griffith would stand for his seat. Griffith was elected to replace Atkin. The rest is history. Griffith became a reforming legislator, Attorney-General, Premier of Queensland, Chief Justice of this State, the drafter of our nation’s Constitution and our nation’s first Chief Justice.

Shortly after the death of her husband, Mary Atkin, wrote to her sons and told them how their father was no longer in pain, and had passed to heaven. She comforted them with the advice that she would return soon to Wales to see them:

“Grandmama will tell you how dear Papa has been very ill, he was so weak that he could not walk about or fish, and had to sit in a chair all day, and cough and be in pain, so God took him away to heaven, because he was fond of him, and now he is quite happy and isn’t ill anymore. Only we shan’t see him again until we die & then if we are very good God will take us too. Papa sent his love to you both and to Baby and a kiss & he said he hoped you would all be very fond of each other and be obedient to Grandpapa and Grandmama and always speak the truth.

I am coming back to you very soon & I want to see my little boys very much. I am so glad to hear that you are well and good. Everybody was so fond of Papa because, he was kind to everyone and they will be fond of you too. Perhaps someday when you are big men, we will come out to Brisbane and you shall finish the work that Papa had only time to begin.”

Dick Atkin never returned to Queensland. But the product of his work as a master craftsman of law and language did. His decisions still guide the law of this country, and the rest of the common law world.

Lord Atkin: from Queensland to the House of Lords

It is fitting that there should be an exhibition about Lord Atkin, and also that parts of the exhibition should be available on-line throughout the common law world. Lord Atkin: from Queensland to the House of Lords explores the influences which made Lord Atkin a great jurist. These include the father who he only knew as a young child, and the remarkable women in his life.

The exhibition was officially opened by Chief Justice Kiefel on the 150th anniversary of Dick Atkin’s birth. It is on five different walls in the Supreme Court of Queensland Library, with the related Donoghue v Stevenson section on the ground floor of the courthouse as part of the Without Fear or Favour exhibition. The “snail in the bottle case” has pride of place there, as a source of education for law students and the general public about the rule of law, including Lord Atkin’s brilliant achievement in distilling the neighbour principle in negligence law.

A Life in Queensland

The section A Life in Queensland describes the Queensland into which Dick Atkin was born. It records some of the impressions the Atkins had about their new home. In March 1865 Robert Atkin wrote to his mother-in-law in Wales:

“The Brisbane river is very lovely, thick evergreens growing into the water on either side. It passes through Brisbane in the shape of a letter S or rather two, one after the other. The houses are in general very pretty, built of wood; the shops in Queen Street are exactly like those in the Edgware Road which project from the brick houses at the back, fine plate glass windows are everywhere … The streets all run at right angles to each other but the houses are built in the most straggling way, and it looks very primitive from a distance. If you can imagine houses built in the woods on either side of Esgair, and a few faintly marked paths, running here and there, you have a very good idea of what is to be seen …”

After a brief stay in Brisbane, the Atkin family settled on a selection at Herbert’s Creek, 100 km from Rockhampton. Drought, harsh conditions and a depressed economy meant that their pastoral ventures were unsuccessful. Robert was misled into buying a half-share in a stock and station agents’ business, which struggled. He liked horses and horse racing but suffered a bad fall from his horse, resulting in his lung condition worsening. This partly contributed to the decision for the family to return to Brisbane. Mary Atkin’s health also was poor.

The Atkins decided to move to Brisbane and for Robert to become a barrister. He registered as a student of law, but because of his work and political commitments never finished those studies.

Later in her life Mary Atkin captured what Brisbane was like in A Talk about Queensland:

“If you could be suddenly pounced down in the middle of the capital town, Brisbane, I don’t think you would know at first you were not in England, you would see Churches & banks & public buildings, and shops with plate glass windows, rows of lamps, a cabstand, pillar posts, and everything else you are accustomed to. But if you left the principal streets, & got into the more open spaces you would see many wooden houses with verandahs round them & strange shrubs & flowers, tall bamboos, Bananas rustling their huge leaves in the wind, great scarlet Hibiscus, Daturas, Oleanders, all sorts of plants that only grow in greenhouses in England. Most likely you would think at first that everyone was staring at you, I am afraid that Brisbanites really do stare at strangers, or “New chums” as they call them, they know each other’s faces so well, that I think they are glad to see someone new, and so apparently thinks the mosquitoes, for they bite new arrivals most unmercifully, you may always know a “New Chum” by his swollen mosquito bitten face.

Brisbane is built on a large tidal river of the same name, great big ships go up and down it, & sharks live in it, once a boy was bathing not far from the town when a shark caught hold of his leg, and would have pulled him down had not someone near rescued him, but alas it was with the loss of part of his leg. Brisbane is about fourteen miles from the sea, & is a very pretty town, for the river winds in and out, so that some streets have the river at both ends, all round it are hills covered with trees to the very top. But everything in and around the town is too English to give you a proper idea of Australia. I should have not have known much about it if I had not lived in the Bush as they call the country districts.”

Robert Atkin worked as a journalist and newspaper editor, and Mary assisted him. Robert’s interest in politics may have been ignited whilst in Central Queensland. In March 1866 Mary wrote to her mother about the sensation Robert created in the speech he gave during an election campaign. His journalistic coverage of Queensland politics led to a short parliamentary career. He was first elected to the Queensland Legislative Assembly on 1 October 1868 as a member for Clermont. He was part of the liberal cause, supported land reform and opposed the power of the squatters. In 1870 he was elected unopposed to the seat of East Moreton which was represented by two members. Significantly, his fellow member after 1871 was William Hemmant.

Robert Atkin joined ex-Premier Lilley and others in an extra-parliamentary group to oppose Premier Palmer’s electoral redistribution bill, which would have reduced the number of seats for Brisbane and its suburbs. They opposed the squattocracy and a group of six members of Parliament from Ipswich and West Moreton who were dubbed “the Ipswich Bunch”. The merchants of Ipswich enjoyed the trade patronage of the Downs squatters, and so the votes of Ipswich MPs usually supported the interests of the squatters. In late 1871 Atkin and other liberals, including Dr O’Doherty, formed a Council of Defence against the squatters and the “Ipswich Bunch”.

The convict doctor who delivered Dick Atkin

The same year, the Protestant Robert Atkin co-founded the non-sectarian Hibernian Society of Queensland with his friend and Irish patriot Dr Kevin O’Doherty. As noted, during his final year of medical studies in Dublin in 1848, O’Doherty was charged over Irish nationalist publications. There were two hung juries. The third convicted. O’Doherty received a ten year sentence and was transported to Tasmania.

After being pardoned, he returned to Dublin where he became a doctor in 1857. He and his wife, the poetess known as “Eva of The Nation”, settled in Brisbane, where he became a leading surgeon. He devised new forms of surgery, and lived in a large house in Ann Street, Brisbane. As an MP, O’Doherty introduced Queensland’s first Public Health Act, and contributed to public education. Like his friend Robert Atkin MP, he opposed trafficking in South Sea Islanders.

In 1886 O’Doherty returned to the UK, was elected to Parliament and supported Home Rule for Ireland. After returning to Queensland, he was unable to re-establish his medical practice due to his association with the cause of Irish nationalism. He became a government doctor and superintendent of quarantine. He died blind and in poverty in 1905. An obituary described him as:

“A warm-hearted, generous, impulsive Irishman, most popular among his professional brethren, and a favourite in every class of society.”

The Hemmant connection

Lord Atkin’s Queensland origins were researched in 2005 by Professor Gerard Carney and his paper can be downloaded here: https://legalheritage.sclqld.org.au/lecture-five-lord-atkin

I drew on Professor Carney’s work in a 2015 Selden Society lecture, which dealt with Lord Atkin’s career and legacy to the rule of law. A fuller account of his career and achievements was published as Lord Atkin: principle and progress (2016) 90 ALJ 711.

Professor Carney’s paper introduces one to William Hemmant, a friend and political ally of Robert Atkin. Hemmant became a successful merchant, and built a large home on the top of Hamilton Hill. During the final years of his life Robert Atkin enjoyed what Lord Atkin later described as the “unremitting care” of William Hemmant. About twenty years later in England, William Hemmant became a supporter of the young barrister, Dick Atkin.

On 17 April 1872, about a month before he died, Robert Atkin, wrote from Hemmant’s home to his son Dick:

“I hope you will always remember that you are the eldest and must show a good example to your brothers, when you are a big man as well as now when you are little. I am getting better and hope to have you dear Dick out with me soon. I am living in a big house on the top of a hill where Lizzie Hemmant lives. You have been there when you were a baby. It is close to the river and the ships and steamers keep passing up and down every day. I am going with Mama, Aunt Grace and Margaret to Sandgate, to the big sea where you used to bathe and dig in the sand. When Dick comes out Papa will take him there to get oysters and shells. Mama bought a piece of land in a new town yesterday for Dick, so that when he is a big man like his Uncle Arthur, for he must grow as big as that, it will be worth a great deal of money. I hope my dear boy that you will always share everything you have with your dear brothers and be kind and affectionate to them. Always tell the truth and be very obedient to your dear Grandmama and grandpapa who are so very kind to you and your brothers. Give my love and great many kisses to Walter and baby and remember me to Jane and tell her how much I am obliged to her for taking such good care of you all. Goodbye my dear little boy, always remember how fond your dear papa was of you and your brothers and always be good and fond of them and your Mama and accept of a quantity of kisses from your affectionate Father.”

These letters from his father, and the letter which his mother wrote to him shortly after his father’s death, must have had a profound influence on Dick Atkin. His mother’s hope that he might return to Brisbane and finish the work of a father who “everyone was so fond of” was not fulfilled. Instead, the values which his father embodied and championed were taken up by Dick Atkin on the other side of the world.

The junior barrister

Dick Atkin was raised in Wales by his loving mother and by his grandmother, Mary Anne Ruck. He won scholarships and was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford. He had no real connection with the law. After completing his Bar exams, he sought out chambers for his pupillage by visiting courts to see the advocates of greatest ability. He settled upon Thomas Scrutton who had a leading practice at the commercial bar. Atkin described Scrutton as the “complete master of the facts and the law”. Atkin persuaded Scrutton to allow him to become his pupil.

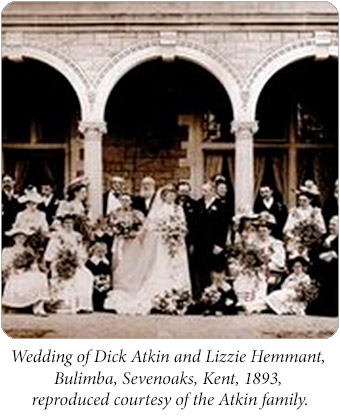

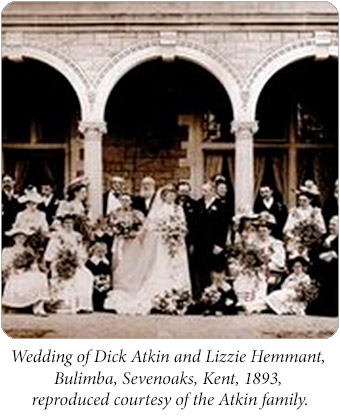

When he was a newly admitted barrister in London, Dick Atkin was invited to William Hemmant’s home in Kent. Hemmant had retired from politics in Queensland and had become the London-based partner of his firm. He built a mansion named Bulimba: interesting that a mansion in Kent should bear an Aboriginal name from Brisbane. When Dick Atkin visited the Hemmant mansion, he met two people who were to change his life. The first was to Lizzie Hemmant, who had been born 12 days before Dick, also at North Quay. They fell in love.

The other important introduction which Dick Atkin made through William Hemmant was to a local solicitor, Norman Herbert Smith. Smith had just started on his own account as a solicitor in the City of London. He promised to give Dick Atkin his first brief and did so. Atkin recalled that it was one of the most difficult cases he had ever had to advise upon in his whole career. It concerned the powers of the executors of a testator domiciled in France under a will in English form dealing with personal property in Constantinople. Smith sought Atkin’s advice about how a Scottish firm which had obtained a judgment in Constantinople against an Italian could enforce the judgment against the Italian’s property in England. Atkin wrote to his mother in March 1891:

“Dearest Mother,

Norman Smith sent the first brief yesterday. It was an opinion as to how a Scotch firm who had obtained judgment in Constantinople against an Italian trading there could get hold of some of the Italian’s property over here. It was a very complicated case and I think I earned my guinea. He sent another case today but that was for an informal kind of opinion and I don’t expect a fee. The first opinion was wanted by 12 o’clock this morning so I was in chambers last night till 11 looking out points. It is very good of him I think to keep his promise so promptly. I am going down to Sandown tomorrow and shall be back on Wednesday. I am looking forward very much of course to spending Easter with Lucy. I expect she will be very glad to hear of the first opinion. The fee came with it so that I have earned my first money. I hope you and Father are quite well as this leave me at present. Best love to you both and Walter.

Always your affectionate son.

Dick” (emphasis added)

In Atkin’s first year at the Bar, Smith was almost the only solicitor who briefed him. He continued to brief Atkin during the whole of his career as a barrister, and went on to build one of the most prestigious firms in the City of London: the firm now named Herbert Smith Freehills.

Atkin began to enjoy a consistent flow of work from the Official Assignee of the Stock Exchange, who administered broking firms which had failed. His first several years at the Bar resulted in annual income of less than or little more than £100. In 1896 the corner was turned when he earned £345.

In retrospect, Atkin’s success at the Bar and on the Bench seems inevitable. However, he came close to leaving the Bar in his early years. Professor Gutteridge’s obituary reported that in Atkin’s early years at the Bar “briefs were few and far between and the outlook was black.” He recalled:

“An occasion on which [Atkin] and I were passing along a London street when Atkin pointed to a building and said: ‘I can never see that without thinking how lucky I have been!’ That building contained the office of a well-known scholastic agency, and Atkin told me how a few years before he had walked into that office with despair in his heart to make inquiries as to the possibility of obtaining a mastership at a public school.”

The Lord Atkin: from Queensland to the House of Lords exhibition includes an image of Atkin’s fee book from his early days at the Bar.

I hope the image of Dick Atkin’s fee book from his first lean years at the Bar encourages very junior barristers to persist like he did. More importantly, I hope it inspires briefing solicitors and more senior barristers to give newly admitted barristers similar opportunities to prove their brilliance.

Influential women

Influential women

Because he was struggling financially at the junior bar, Dick Atkin and Lizzie Hemmant were engaged for five years. They married in 1893. The photograph of their wedding party at Bulimba in Kent has pride of place in the exhibition.

Lizzie Hemmant, later Lady Atkin, was a formidable woman. Before the First World War she bought a car and went shopping in it. Her son reported:

“In later years she patronised the Army and Navy Stores into which she would enter majestically leading her bulldog and smoking her cigarette knowing confidently that none of the staff would think of reminding her that both dogs and cigarettes were forbidden in the Stores. ”

One hundred years ago, in late 1917, Lady Atkin’s life was darkened when she lost her eldest son and her brother on the same day in the same battle.

The Exhibition features the influential women in Lord Atkin’s life: the mother and the grandmother who raised him in Wales, his wife and his six daughters. Many of the images in the exhibition, like the wedding photo and the grand photo of Lady Atkin in 1929 were supplied by members of the Atkin family and by Gray’s Inn.

The physical exhibition and its on-line version

The Exhibition aims to capture in a few words and images the Queensland into which Dick Atkin was born, and the people who influenced his life. It also aims to educate the public about his legacy. Parts of it are on-line: https://legalheritage.sclqld.org.au/exhibitions/lordatkin. However, the actual exhibition is more comprehensive and colourful, with many interesting images and a design which cannot be captured on-line. You should visit it, if you can.

To complement the Donoghue v Stevenson section, the Supreme Court Library has created YouTube videos featuring three of our finest tort scholars, Professor Mark Lunney from the University of New England, Professor Kit Barker from the University of Queensland and Dr Kylie Burns from Griffith University. These videos were produced at the

T C Beirne School of Law at the University of Queensland:

https://legalheritage.sclqld.org.au/donoghue-v-stevenson-1932-ac-562

Lord Atkin championed the education of law in universities, the improvement of practical legal education, and the rejuvenation of Gray’s Inn. The contributions to the exhibition by our academic colleagues will allow law students and lawyers to better understand the law which Lord Atkin made. Their short video lessons will be available throughout the common law world: from Brisbane to Papua New-Guinea, to Burma, to Birmingham.

Liversidge v Anderson

Justice Keane’s video explains why we celebrate Lord Atkin. He describes Lord Atkin’s famous judgment in Liversidge v Anderson as a ringing blow for liberty and equality under the rule of law, and for the integrity of the English language itself. The part of the exhibition about Liversidge v Anderson is the result of the scholarship and toil of Dr Karen Schulz from Griffith University. She had to compress thousands of words of scholarship into the few hundred words which made it onto the walls of the exhibition.

https://legalheritage.sclqld.org.au/liversidge-v-anderson-1942-ac-206

When he wrote his famous judgment in Liversidge v Anderson Lord Atkin was a widower, in his early 70’s, whose home in Wales also became home to grandchildren. As he wrote his judgments in his study, young children were running around his home, and one of his daughters was running a school there, teaching children who, like some of his grandchildren, had been forced to leave London during the blitz. You will see in the exhibition a photo of three little girls at a fair in Wales during the war. They are three of Lord Atkin’s many grandchildren. Their oral histories about their famous grandfather have recently been recorded by the Library, and will be released early in 2018.

In them you will hear how Alice in Wonderland was a favourite book of the granddaughters with whom he lived, and how these children, under the artistic direction of their mother, would act out the parts. So we may have discovered the literary source for parts of the famous dissent in which he ridiculed the views of the majority in that case:

“I protest, even if I do it alone, against a strained construction put on words with the effect of giving an uncontrolled power of imprisonment to the minister. To recapitulate: The words have only one meaning. They are used with that meaning in statements of the common law and in statutes. They have never been used in the sense now imputed to them. They are used in the Defence Regulations in the natural meaning, and, when it is intended to express the meaning now imputed to them, different and apt words are used in the regulations generally and in this regulation in particular. Even if it were relevant, which it is not, there is no absurdity or no such degree of public mischief as would lead to a non-natural construction.

I know of only one authority which might justify the suggested method of construction: ‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less.’ ‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’ ‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master — that’s all.’ After all this long discussion the question is whether the words ‘If a man has’ can mean ‘If a man thinks he has.’ I am of opinion that they cannot, and that the case should be decided accordingly.” [1942] AC 206, 244—45, citations omitted.

When Vice Chancellor Simon (who had not sat in the case) read Atkin’s draft judgment and tried to persuade Atkin to omit the Alice in Wonderland jibe, Atkin responded:

“I consider that I have destroyed [the majority interpretation] on every legal ground: and it seems to me fair to conclude with a dose of ridicule.”

Atkin at War

In 1940 Atkin corresponded with Dr H V Evatt QC. Atkin had read with great interest Evatt’s story of Governor Bligh, and wrote:

“How little the public realise how dependent they are for their happiness on an impartial administration of justice. I have often thought it is like oxygen in the air: they know and care nothing about it until it is withdrawn.”

The letter concluded: “ We hear no war news that you do not get: and that seems to me precious little. However we are determined to put an end to the gangsters as you all are.”

In May 1940 Atkin spoke in Gray’s Inn at a reception for refugee lawyers, including Dr Ernst Wolff, who had been President of the Berlin Bar and the General Council of the German Bar before Hitler’s rise to power. He later became President of the Supreme Court in the British Zone of Germany. After the reception Dr Wolff wrote to Lord Atkin that his “kind words of sympathy for our situation went to our hearts.” Wolff wrote about Britain’s fight against the “conspiracy of piracy” that the German lawyers had suffered, and hoped that after Nazi Germany was destroyed “law can again prevail”.

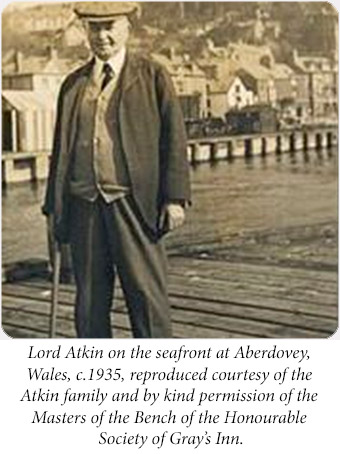

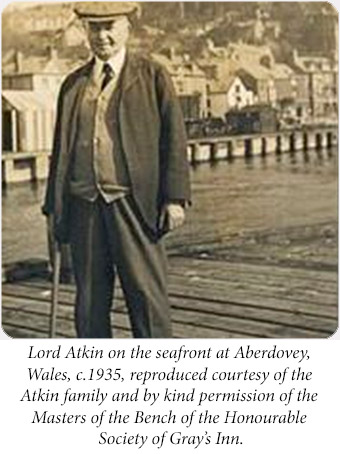

The peer photographed on the pier

The peer photographed on the pier

At the Exhibition’s entry you will see a photo of Lord Atkin on a pier at Aberdovey in Wales. His granddaughter Mrs Elizabeth Barry recalls in her oral history:

“He went down to the jetty because they were about to demolish it as the war started, and they thought we were going to be invaded. He went down and said ‘No, stop that’. It’s a very typical photograph of him because he liked to wear his old suits. It was a place where he could relax.”

She also said:

“He was very good with people. The people in Aberdovey really loved him, and his study was open all the time to anybody who wanted to come and get advice.”

As a child Lord Atkin had been told by his dying father to be good and kind, truthful and honourable. He certainly fulfilled his father’s wishes.

The Honorary Australian

In 1933 Justice Evatt of the High Court of Australia wrote to Lord Atkin congratulating him on his judgment in Donoghue v Stevenson. Evatt wrote of Atkin’s achievement: “the common law is again shown capable of meeting modern conditions of industrialization, and of striking through forms of legal separateness to reality.”

Ten years later, in 1943, long before D-Day, the Allies began to think about how to punish war criminals. As Australia’s External Affairs Minister, Dr Evatt asked Australia’s High Commissioner in London to approach Lord Atkin to be Australia’s representative on the War Crimes Commission. Evatt’s telegram, which you can see in the exhibition, concluded:

“As you know, Atkin is Australian born and is an outstanding jurist”.

In the final year of his life, Lord Atkin served as Australia’s representative on the War Crimes Commission. He publicly championed the idea that there were crimes which transcended all domestic laws, and were (to use the words of a letter he wrote to The Times on 30 December 1943) “offences against the conscience of civilized humanity”. He thought this might require ad hoc international tribunals to be constituted.

We are fortunate to have had a person with Atkin’s uncompromising sense of justice as Australia’s representative in devising a system of justice which would apply to enemies of democracy who committed crimes against humanity.

The Atkin Monument and its restoration

Late in his life Lord Atkin wrote “My father must have been a man of exceptional gifts” and he pointed to the words inscribed on a monument at Sandgate about his father. They include that Robert Atkin was “devoted to the promotion of a patriotic union among his countrymen, irrespective of class or creed, combined with a loyal allegiance to the land of their adoption”.

Lord Atkin was never a rich man: after all he had six daughters to educate; twice as many daughters as the perennially poor Welsh barrister in the Rumpole series. In 1937, he personally funded the restoration of the monument at Sandgate, after it had fallen into disrepair. When I first saw it two years ago the monument was again in a terrible state of disrepair. Since then a group of citizens associated with the Sandgate Museum and Historical Society Inc, which is a registered charity for tax and other purposes, have been jumping through the heritage and bureaucratic hoops, and trying to raise funds to restore the monument. In the last few weeks work has begun in earnest. Engineers, arborists and stonemasons have to be paid. I encourage barristers and others contribute to this project.

It is hard to imagine anything which would give Lord Atkin and his family greater pleasure than to restore the monument which he restored 80 years ago. It is a monument to the man who inspired Dick Atkin to do go great work throughout his life.

To support the Atkin Monument Restoration Project or to find out more about it contact:

donations@sandgatemuseum.com.au or call Ms Pam Verney at 0410 327 095.

You can also visit and download a Fact Sheet about the restoration project:

https://www.facebook.com/roberttraversatkin/

Justice Peter Applegarth

Robert Atkin and Kevin O’Doherty may have had their differences over Irish independence, but as public figures and unpaid Members of Parliament, these friends had a shared vision about Queensland’s future. They and other reformers, like Charles Lilley, opposed the vested interests of the squattocracy. Robert Atkin argued for fairness towards people in the North, for new railways, and for new industries of cotton and sugar. Atkin described the Polynesian Labourers Act as a legalised system of kidnapping. He and his colleagues did not want Queensland to become a plantation state, built on slavery, like the Deep South of the United States had been.

Robert Atkin and Kevin O’Doherty may have had their differences over Irish independence, but as public figures and unpaid Members of Parliament, these friends had a shared vision about Queensland’s future. They and other reformers, like Charles Lilley, opposed the vested interests of the squattocracy. Robert Atkin argued for fairness towards people in the North, for new railways, and for new industries of cotton and sugar. Atkin described the Polynesian Labourers Act as a legalised system of kidnapping. He and his colleagues did not want Queensland to become a plantation state, built on slavery, like the Deep South of the United States had been. Influential women

Influential women The peer photographed on the pier

The peer photographed on the pier