FEATURE ARTICLE -

Issue 58 Articles, Issue 58: Dec 2012

The clause was:

“7. I APPOINT absolutely and irrevocably all my children as beneficiaries of the REBECCA JAN DOWN Trust, but direct my Trustees to make no distribution to the beneficiaries until such time as the REBECCA JAN DOWN is deceased.

Rebecca Jan Down was the deceased daughter who had Down syndrome. In considering the meaning of the words “all my children”, her Honour said:

“[8] The description “children” in its ordinary sense refers to natural children, although it can be construed as extending to step-children if the context and circumstances of the case (based on admissible evidence) show this is the preferable construction. That is, the words, ‘all my children’ should be construed as meaning the first to sixth respondents, unless there is something in the will, or the context and surrounding circumstances to which I am entitled to have regard, which indicates that in this will the phrase, ‘all my children’ should be interpreted to include the three adult children of Patricia Down.

[9] It might be that the word, ‘all’ before the words ‘my children’ gives some indication that a more extensive class of children, than the testator’s natural children, was intended. I would not so construe the word ‘all’ in this case. The intention of clause 7 seems to me to be to ensure that one of the testator’s children, Rebecca, was particularly cared for due to her special vulnerabilities and needs. Having made special provision for that one child the phrase ‘all my children’ is apt to refer to the group of the testator’s other children, in contradistinction to his child Rebecca, as to the remaining gift. In those circumstances I do not see the word ‘all’ as expanding the class of children from natural children to include step-children.

[10] Again confining myself to the words of the will, the testator has made an initial gift to his wife (should she survive him), but in the event that she did not, the remaining terms of his will do not mention the children of Patricia Down by name, in the way that three of his natural children are mentioned. The executors, in the event that Patricia Down does not survive the testator, are named as two of his natural children. Rebecca is also named particularly, due to her circumstances. If, for example, one of the seventh to ninth respondents had been named as executor, or described, as are Helen and Shirley, as a daughter (or son), that might well be an indication from the language of the will itself that the phrase ‘all my children’ was to include step-children as well as natural children. This point is not decisive, but it is an indicator relevant in construing the will.

[12] The facts as to Mr Down’s first marriage and six children, and to Patricia Down’s three adult children are obviously facts to which the Court may have regard. So are the ages of those children at the time the will was made and the age of the testator and Mrs Patricia Down at the time the will was made. The dates of birth of the seventh to ninth respondents respectively are 7 March 1957, 3 July 1958 and 23 May 1959. So that at the time the will was made they were 43, 41 and 39 years old. Patricia Down was 75 at the time of her death in 2006, making her around 68 at the time of her marriage to Gilbert Down.

[13] There was no pre-existing Rebecca Jan Down Trust as at the time of the subject will. In August 1995 Mr Gilbert Down had made a previous will and on the same day a document was drawn up for a trust named the Down Family Trust. This document is much more complicated than the simple form of the will. Its provisions differ in substance from the dispositions in the will. There is no evidence that the Down Family Trust ever operated. ….

[17] On the material before me I am not convinced that circumstances or context admissible in evidence on this application takes the phrase ‘all my children’ outside its ordinary meaning so that it extends to the adult step-children of the testator. In those circumstances I declare that on the proper construction of the will of Gilbert James Down dated 17 December 1999 the will:

(a) directs the executors to sell all the property of the testator and hold that property on trust for Rebecca Jan Down for her life, and

(b) upon the death of Rebecca Jan Down to hold that property on trust for Kenneth Gilbert Down, Geoffrey Phillip Down, Raymond James Down, Helen Doris Kathleen Thomson and Shirley Ann Sommer.”

In Gamer v Whip [2012] QSC 209 the applicant sought orders that:

(a) the proper construction of the document signed by GLENDA MARY CATHERINE PAGE deceased dated 28 November 2011 and headed ‘To the Executor of the will of Joan Kathleen Atkinson deceased’, Ms Page intended to assign her interest in the estate of JOAN KATHLEEN ATKINSON deceased to Janet Catherine Christiansen and Monica Julie Jensen; and

(b) A declaration that the document is not a codicil pursuant to s 18 of the Succession Act 1981.

The document was as follows:

“I Glenda Mary Catherine Page being a beneficiary under the will of Joan Kathleen Atkinson relinquish my beneficial entitlements under the will and bequeath the same in equal shares to Janet Catherine Christiansen and Monica Julie Jensen, who are also beneficiaries under the said will.”

On 26 or 27 November 2011, Ms Page was informed that she was a beneficiary in the estate of Ms Atkinson who had died a month earlier. Ms Page was very ill and after preparing the document she had a Justice of the Peace witness her signature on the document.

Justice Atkinson observed:

“The difficulty in the interpretation of the document arises from the use of words by Ms Page without legal advice which on their face, if used alone, would suggest a particular interpretation. However, when the document is read as a whole, as it should be, it appears to me that the interpretation becomes reasonably clear.”35

Both counsel agree that it could not be considered to be an informal codicil to Ms Page’s will. Section 18 of the Succession Act 1981 (Qld) gives the Court wide power to dispense with the execution requirements for a will or an alteration or a revocation and applies to any document, or indeed any part of a document, that purports to state the testamentary intentions of a deceased person and has not been executed as the Succession Act otherwise requires.

However, the reason why this broad power is not apt to make this document a codicil to the will is that the document does not purport to give effect to any testamentary intention of Ms Page. It is true that the word ‘bequeath’ is used, but it is not used in the sense that she intends the document to operate on her death. Indeed, her intention from the document and from her behaviour in sending it to the executor of Ms Atkinson’s estate is that it was to operate with regard to her share of Ms Atkinson’s estate, which she wished to be given to Ms Christiansen and Ms Jensen, rather than receive the benefit of it herself.

There is nothing in the document to suggest, other than incorrect use of the word ‘bequeath’, that it is meant to be a testamentary document, and I am in those circumstances prepared to declare that it does not operate as a codicil to Ms Page’s will.”

Her Honour also concluded that the document was an assignment of her interest in the estate of Joan Kathleen Atkinson, not a renunciation of her entitlement.

In Parkinson v Diabetes Australia [2011] NSWSC 1530 the issue was the correct identity of the charity that was to receive a one-third share of the whole of the deceased’s estate. The remaining two-thirds share was received by two other charities.

The sub-clause of the residuary clause of the Will36 was a follows:

“(b) As to One (1) part thereof for DIABETES AUSTRALIA and I DIRECT that the receipt of the Secretary or other authorised officer for the time being shall be a sufficient discharge to my Trustee;”

Two incorporated bodies existed, one named Diabetes Australia and one named Diabetes Australia-New South Wales. The question was which body did the testator intended to be the beneficiary. Justice Bryson considered the history of the organisations involved in diabetes and observed:

“4 There have been organisations in New South Wales concerned with the interests of persons suffering from diabetes for over seventy years and both defendants have associations with earlier bodies.

5 People who suffer from diabetes have many shared interests and needs including interests in dealings with the Commonwealth government and its National Diabetes Services Scheme. There are now eight State and Territory diabetes organisations and there is also a Federal body which functions as a national secretariat for government lobbying and policy development.

6 The second defendant is the organisation which functions in New South Wales. It was incorporated on 15 October 1976. It seems that a predecessor existed earlier. When incorporated its name was Diabetic Association of New South Wales but by the time Mr Poore’s activities can be seen from evidence its name had become Diabetes Australia – New South Wales. It changed its name again on 3 December 2010 and its name now is Australian Diabetes Council.

7 The first defendant was created at the initiative of State and Territory organisations. Its office and its main activities are in Canberra. It was incorporated on 8 September 1976 and was then named The Diabetes Federation of Australia. Later its name was changed to Australian Diabetes Foundation. Then on 8 November 1988 its name was changed to Diabetes Australia and it still has that name.

8 It is a company limited by guarantee and when it took its present name it was licensed to omit the word “Limited” from its name. Some witnesses spoke of it as once being named Diabetes Australia Limited and being sometimes referred to even now by the abbreviation “DAL” but search papers of ASIC records in evidence do not show that it ever had the word “Limited” as part of its name. Yet that word appears at least once in its documents in evidence: Court book 34, front page of copy of its Constitution.

9 The first defendant is a national body and its principal objects include promotion of research into all aspects of diabetes, prevention and early detection and advocating access to treatment. Its inaugural members included twenty-five individuals who were founding life members. There were also State associations. Not all State associations still are members. There are other member organisations and special members. It seems on the terms of its constitution that it is possible that an individual might become a member or associate member but this is not usual. Its members are almost all organisations, not individuals.

10 The second defendant resigned from the first defendant in 2008. Mr Poore cannot ever have been a member of the first defendant.

11 The second defendant’s members are mainly individuals. There are perhaps thousands of members. Its activities include considerable attention to membership and subscriptions. It maintains active communication with members and with community organisations to which members belong. There are some special classes but generally membership must be renewed annually and a membership fee must be paid annually in most cases.

12 The second defendant maintains records of personal information about its members relevant to its activities. In these records little was known of Mr Poore in the second defendant’s office. However, its records do show that he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in 1974. He made a payment which seems to show that he had become a member or had given a donor’s pledge by 18 November 1987. He clearly appears in records as a concession member from about 28 April 2003 onwards and he may have been a subscribing member earlier.

13 In the ordinary course he would have received many communications from the second defendant. An example is the membership renewal form used by the second defendant from 2004 to 2006. At the head of its front page is the name Diabetes Australia, with the second defendant’s ACN number. The same appears at the head of the second page and there are other references to the second defendant as DA-NSW and as Diabetes Australia-NSW. Its email address and website include “diabetesnsw”.

14 Mr Poore probably received other correspondence each year or more often on a letterhead which included the name, Diabetes Australia-New South Wales and DIABETES AUSTRALIA-NSW, with references in the body of the letter in similar terms.”

After examining the publications by the two defendants Bryson J concluded:

“20 A person who carefully or regularly read the quarterly magazine could not fail to know that there were separate State and national entities with similar names. A person who gave them less than close attention could easily miss this distinction.

21 Nothing is known as to Mr Poore’s personal characteristics or acuity except that he was employed as an advertising clerk and that he was interested enough to make donations over many years which suggests that he could well have thought about where his donations were going. He was interested enough to designate DART repeatedly for his donations. He left estate assets which suggest a careful and regular life. He used the name Diabetes Australia twice in wills. Otherwise, nothing is known about how he used language when dealing with organisations in the diabetes field. Practically nothing is known about how he used language at all.”

After reviewing the case authorities on the description of charities [see paragraphs 27 to 42 and in particular the House of Lords decision in National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children v Scottish National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children [1915] AC 207] Bryson J concluded:

“43 My principal guide is the National Society decision. The primary question is about the language used by the testator, how he used language and what the words used meant when he used them.

44 In the background is the important question, what would the testator say if he really did intend to give his gift to the person whose exact name he gave? I see this consideration as part of the basis of readiness to speak of the starting point as a presumption or strong presumption in favour of literal meaning. …

48 None of the evidence in this case really shows anything about Mr Poore’s use of language and, in particular, the evidence does not show anything about how he identified one or other of the entities operating in this field. The evidence gives only the most oblique and indeterminate indications of how Mr Poore used language.

49 The fact that he had a long continuing association with the second defendant does not explain what he meant when he gave the name of the first defendant. That consideration could only have much force if it were proved that he did not know that the first defendant existed and had its own name. There is no proof of that. He could well have known about the first defendant and its name. He could well have been aware that there were two different societies. That information was repeatedly made available to him. It could be understood from the quarterly magazines. The full name of the second defendant and also the full name of the first defendant were often before him.

50 It would only be a speculation to suppose or act on the basis that he did not know that there were two and that each had a name of its own. Mr Poore had strong associations with the second defendant. If anything, this suggests that he would have had means of knowing its correct name and using it, if he meant to refer to it on a serious occasion.

51 In this case, as in the National Society case, there is a need for clear demonstration that where the correct name is used something else was intended. In the present case the evidence before me does not resolve the doubt in a clear way, it does not resolve it in favour of the second defendant. Nothing overcomes the question: What would Mr Poore have said if he did intend to benefit the first defendant?

52 My conclusion is that he named the first defendant and the evidence does not show that he did not mean what he said. I intend to dispose of the case in that sense.”

The significant issue arising from this decision for solicitors is the need to correctly identify the correct names of beneficiaries chosen by the testator; and if the beneficiary is a charity its preferred bequest clause. If there are two or more charities with similar names, further questions need to be put to the testator and to record their instructions as to the identity of the charity.

In Kean v Murphy [2012] NSWSC 948 the issue was whether by clause 5 of her home-made Will, Sister Eileen Kean left her estate to be divided equally between all of the children of her three named siblings or whether she left her estate to be divided into three equal parts with each part then to be divided equally between the children of each of her three named siblings, with the result that the children of each sibling would receive an equal share of a one-third interest [i.e. per capita or per stirpes?].

The clause in question was as follows:

“5. Residuary/Residue of my Estate

I direct my Executor(s) to pay all my debts and then I give the residue whole of my estate to that I may possess at death to be divided evenly among the children of my brothers John Francis (dec), Thomas James (dec) and my sister Doreen Phyllis – the house to be sold. Should any of the family desire possessions in the house – they may take them – otherwise they should be sold. A small a/c is located in the St George Bank.

All property, goods and money to be divided into three equal parts – then divided evenly amongst the groups of my three siblings.”

In considering the issue Justice Ball said:

In considering the issue Justice Ball said:

“15 In construing cl 5 of the will, it is important to bear in mind that it was drafted without legal assistance. Sister Eileen was obviously an intelligent and well educated person, but she was old and frail at the time she prepared her will and it cannot be expected that she would use language as precisely as a lawyer normally would.

16 Clause 5 has two paragraphs. The critical words of the first paragraph are the words that state that the whole of her estate is ‘to be divided evenly among the children of my brothers John Francis (dec), Thomas James (dec) and my sister Doreen Phyllis’.

17 It is clear that by ‘evenly’ Sister Eileen meant ‘equally’ and taken alone those words suggest that her estate was to be divided equally between the children of Sister Eileen’s named siblings.

18 However, the second paragraph of cl 5 provides:

‘All property, goods and money to be divided into three equal parts – then divided evenly amongst the groups of my three siblings.’

19 It is not disputed, nor could it be, that the reference to ‘[a]ll property, goods and money’ is a reference to the whole of Sister Eileen’s estate. Nor is it disputed that the reference to ‘my three siblings’ is a reference back to the three siblings named in the previous paragraph.

20 In my opinion, it is clear that Sister Eileen included the second paragraph as an explicit statement of how she intended the first paragraph to operate. In my opinion, that explicit statement is clear. First, the paragraph states that Sister Eileen’s estate is to be divided into three equal parts. Then (to use Sister Eileen’s word), the result is to be divided equally among the identified groups. What Sister Eileen must have intended was that each one third part would be divided equally between the members of one of the three identified group. If what she had intended was that the whole be divided, there would have been no purpose in providing first for the division into three equal parts. …

25 It is true that the first paragraph read alone suggests that the quality of evenness or equality is to be measured by reference to what each beneficiary receives and not what each family group receives. However, as I have said, the second paragraph was to spell out in more detail how the distribution contemplated by the first paragraph was to occur. For the reasons I have given, in my opinion the purpose of the second paragraph is clear. Having regard to the terms of the second paragraph, I do not think it does any great violence to the first paragraph to interpret it so that the word ‘evenly’ applies to the three groups of children rather than to each individual child.

26 I should add that I do not think that the conclusion I have reached is so extraordinary that the court should strive to give the words some other meaning. Sister Eileen had a close relationship with her three siblings and had relationships of various degrees of closeness with their children. There is nothing odd in those circumstances in a decision to seek to treat the three families equally.

27 It follows from what I have said that there is no ambiguity in cl 5. Consequently, the evidence of intention is not admissible.”

Construction issues with trust deeds

Trusts are obligations recognised and enforced in equity. They may be created by unilateral declaration of the settlor. Consideration (moving from the trustee upon whom the trust property is settled) is not generally essential. Third party beneficiaries are the appropriate parties to enforce the trust.

Trust terms need not be set out by the trust creator, so long as there is sufficient certainty of subject-matter and certainty of objects.

Powers, duties and liabilities of trustees, rights of beneficiaries and whether the settler has power to revoke the trust may all, in an appropriate case, be established by the rules of equity and legislation.

While, the origins and nature of contracts and trusts are very different Mason and Deane JJ observed in Gosper v Sawyer (1985) 160 CLR 548 at 568-569:

“There is … no dichotomy between the two. The contractual relationship provides one of the most common bases for the establishment or implication and for the definition of a trust.”37

A trust could be a sham if the settlor has no intention to create a trust although this is likely to be very rare following the decision of the High Court in Byrnes v Kendle (2011) 243 CLR 253. The High Court in deliberating on whether an express trust existed, considered at length what was meant by the intention of a settlor to create the trust. It was held that the objective intention is derived from the circumstances and not the subjective intention.

“The authorities establish that in relation to trusts, the search for ‘intention’ is only a search for the intention as revealed in the words the parties used, amplified by facts known to the parties”, – per Heydon and Crennan JJ in Byrnes v Kendle at [105].

The circumstances in Byrnes v Kendle were that Mrs Byrnes and Mr Kendle were married in 1980. For both of them it was a second marriage, and they both had children from their previous marriages. Mr Kendle purchased a property in Brighton, South Australia in 1984. In 1989 Mrs Byrnes & Mr Kendle executed a deed which included a provision in relation to the Brighton property that Mr Kendle “… stands possessed of and holds one undivided half interest in the Property as tenant in common upon trust for [Mrs Byrnes] absolutely”.

In 1994 the Brighton property was sold and a property at Murray Bridge was purchased using the proceeds of the sale of the Brighton Property. In 1997 Mrs Byrnes & Mr Kendle executed a further deed acknowledging that:

“… each party was entitled to a ½ interest as tenants in common of the property … and that [Mr Kendle], who was registered proprietor of the Original Property, stood possessed of an undivided half interest in the Original Property upon trust for [Mrs Byrnes] absolutely”; and

“that their respective entitlements to interests in the Original Property are transposed into interests in the New Property.”

In 2001, Mrs Byrnes & Mr Kendle moved out of the Murray Bridge property. During the period from 2001 to 2007 Mr Kendle let the property to his son, Kym, for $125.00 per week. However, Kym only paid rent for the first two weeks. After the first two weeks, Mr Kendle did not collect the rent and Mrs Byrnes not press him did to collect the unpaid rent or evict Kym and obtain another tenant. It was accepted at trial that Kym should have paid $36,150.00 for his occupation the property.

In 2007, Mrs Byrnes and Mr Kendle separated. In March 2007, Mrs Byrnes assigned her interest in the property to her son Martin for consideration of $40,000.

Mrs Byrnes and her son commenced a proceedings against Mr Kendle, for, breach of trust and sought relief in the form of a half share of the net proceeds of sale of the Murray Bridge property, with any monies found to be due, as a result of an account for the uncollected rent, to be deducted from Mr Kendle’s share of the net proceeds.

In July 2007 Kym vacated the property and Mr Kendle’s grandson commenced occupation paying rent of $100 per week, which was used by Mr Kendle’s daughter to off-set her expenses in caring for her father. None of the rent was paid to Mrs Byrnes.

In the District Court, Boylan DCJ considered the case turned on Mr Kendle’s intention in determining whether or not an express trust has been created. It was held that the court may look at evidence outside the trust deed to determine the intention of the alleged settlor. The decision was:

(a) A declaration that Mr Kendle held one half of the proceeds of sale on trust for Mr Byrnes;

(b) The claim based on breaches of trust including the alleged failure to collect rent was dismissed; and

(c) that Mr Byrnes and Mrs Byrnes pay Mr Kendle’s costs.

The appeal by Mrs Byrnes to the Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia was dismissed. The Full Court found that a trust had been created, it was held that while Mr Kendle did not have a duty with respect to the recovery of rent and he was not subject to the duties that would normally be imposed on a trustee who rents out a property because Mrs Byrnes had consented or acquiesced in Mr Kendle’s actions as trustee.

In the appeal to the High Court of Australia the key issues were:

(1) Was there a trust created by the 1997 Deed?

(2) If so, what were the duties of Mr Kendle with respect to renting out the property?

(3) Was there a breach of those duties?

(4) If so, did Mrs Byrnes (and her son as assignee) consent to or acquiesce in the breach?

(5) If she did not, what is the appropriate form of relief for the breach of trust by Mr Kendle?

The first question was decided unanimously in favour of Mrs Byrnes.38 Section 29(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1936 (SA)39 required a declaration of trust regarding any land or an interest in land, is to be “manifested and proved by some writing signed by some person who is able to declare such a trust”. There was no informality, because the trust was manifested and proved by the words “upon trust” used in the 1989 Deed.

The High Court affirmed the position that the objective theory prevails in respect of trusts, just as it does in respect of contracts. Gummow and Hayne JJ quoted the following passage from the judgment of Lord Millett in Twinsectra Limited v Yardley40 with approval:

“A settlor must, of course, possess the necessary intention to create a trust, but his subjective intentions are irrelevant. If he enters into arrangements which have the effect of creating a trust, it is not necessary that he should appreciate that they do so; it is sufficient that he intends to enter into them.”

It was also stated by Gummow and Hayne JJ that:41

“The fundamental rule of interpretation of the 1997 Deed is that the expressed intention of the parties is to be found in the answer to the question, ‘What is the meaning of what the parties have said?’, not to the question, ‘What did the parties mean to say?’ The point is made as follows, with reference to several decisions of Lord Wensleydale, in Norton on Deeds:

‘The word ‘intention’ may be understood in two senses, as descriptive either (1) of that which the parties intended to do, or (2) of the meaning of the words that they have employed; here it is used in the latter sense.’”

French CJ agreed with Gummow and Hayne JJ on this issue.42

The view of Heydon and Crennan JJ was that the principles in contract apply equally to trusts.43

The position now is that the law of deeds, the law of contract, and the law of trusts speak with one voice on this issue: an objective intention prevails over the subjective intention of the parties.

The High Court also found for Mrs Byrnes and her son on the breach of trust claim and she received half of the net proceeds of sale of the property plus half the rent which ought to have been collected, less outgoings paid by Mr Kendle during that time, as compensation for breach of trust.

“Wills and the construction of them do more to perplex a man than any other learning …”

Glenn Dickson

Copyright

© These materials are subject to copyright which is retained by the author. No part may be reproduced, adapted or communicated without consent except as permitted under applicable copyright law.

Disclaimer

This seminar paper is intended only to provide a summary of the subject matter covered. It does not purport to be comprehensive or to render legal advice. Readers should not act on the basis of any matter contained in this seminar paper without first obtaining their own professional advice.

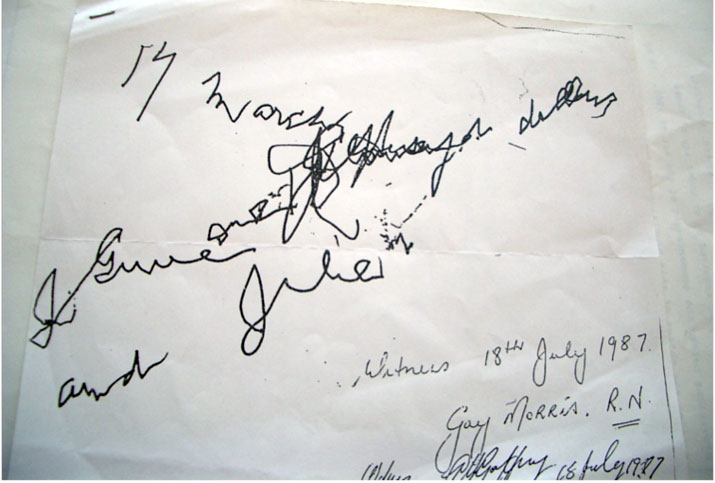

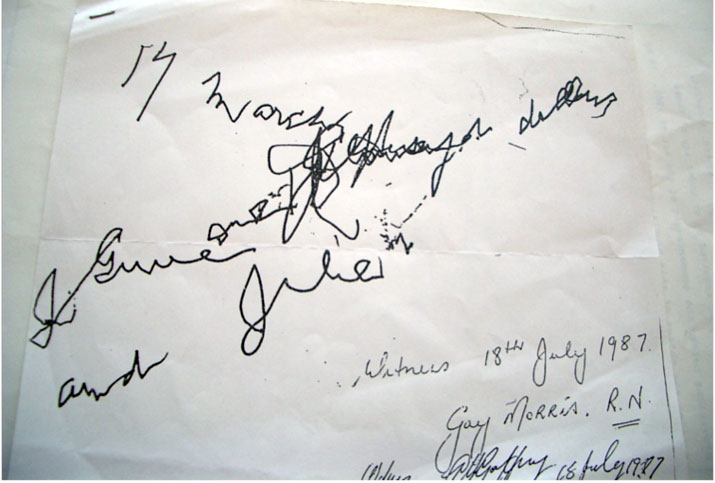

APPENDIX A

“I give everything to my darling wife Julie”

Footnotes

35. At page 1-5.

36. It appears that it was a home-made Will.

37. In a passage quoted with approval by Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ in Associated Alloys Pty Ltd v ACN 001 452 106 (in liq) (2000) 202 CLR 588 at [27].

38. At par [46].

39. Which is similar to section 11 Property Law Act 1974 (Qld)

40. [2002] 2 AC 164 at [71].

41. (2011) 243 CLR 253 at [53].

42. (2011) 243 CLR 253 at [17].

43. (2011) 243 CLR 253 at [102].

44. Roberts v Roberts (1613) 2 Bulst 124 at 130; 80 ER 1002 per Lord Coke CJ.

In considering the issue Justice Ball said:

In considering the issue Justice Ball said: